LIKE MOST ENTHUSIASTS, I nurse my own enthusiasms and ignore the joys of others. I come late to inspirations that have been whispering in my ear for years. So it happens that I have only recently arrived at Brian Eno, about whom I knew next to nothing but now would describe this way: lovely bald man who sees what he hears and invents dream noise that somehow seeps into the very furniture of our lives. His relationship to sound is not like yours or mine. If you can have him in your band, you probably will.

My unschooled image of Eno had been that of a hyper-serious musical string-puller who wrested David Byrne away from the other Heads and forced him to make “Remain In Light” in order to reroute popular music. He had also, in my mind, become attached to the dreaded word “electronic” at a time when I disdained button pushers who spewed artificial womb noise instead of opting for the moral fecundity of drums and guitars.

Furthermore, he didn’t seem to say much, or sing much, and I liked words. I even preferred paintings with words on them. Music without words had no meaning assigned and therefore I was twice as likely to misunderstand it.

So what changed? Everything and nothing. I discovered that Eno liked words too, at least sometimes, and that when he used them he was as witty as Randy Newman without the self-flagellation. And that on many of his early adventures he was wise enough to bring along Robert Fripp, whose electric guitar sounded like a cat with its tail caught in a car door.

Plus he sang in funny voices.

If you know all this already you can quit reading, but don’t. There is much here to make a person happy. Such as:

Given the chance

I’ll die like a baby

on some faraway beach

when the season’s over

Unlikely

I’ll be remembered

as the tide brushes sand in my eyes

I’ll drift away

Cast up on a plateau

with only one memory

a single syllable

oh li lo li lo

(“On Some Faraway Beach”)

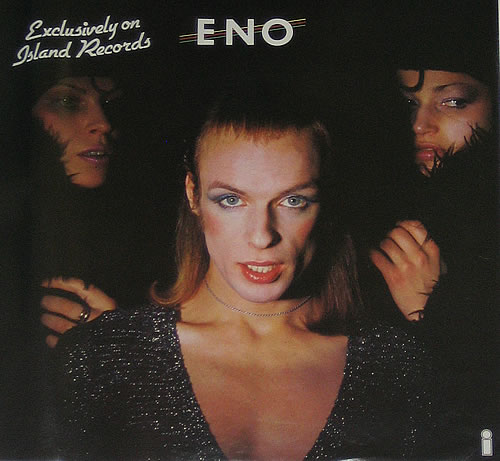

While dying like a baby on a beach may not be for everyone, the point is made: Brian Eno, the ultra-skinny glam boy with long but thinning hair, staring stony-faced and lady-like from the cover of Here Come the Warm Jets, is not a manikin twirling knobs: he’s emotional! The buttons he pushes evince an actual feeling. Sometimes they tell jokes. He’s often amused, and when he has a gripe with someone or something, his amusement, rather than disappearing, blossoms. “Blank Frank,” all-around evil personage of Warm Jets’ song of the same name, will not only “look at you sideways” and do unspeakable things “in people’s driveways” (presumably because this rhymes with sideways, sort of); he also speaks “in incomprehensible proverbs” and is everywhere and in all things:

Blank Frank is the siren

he’s the air-raid, he’s the crater

He’s on the menu on the table

he’s the knife and he’s the waiter.

Blank Frank is both the London blitz and a nuisance at dinner. If complaining about one thing, why not everything? Robert Fripp’s guitar buzzes the molars while Eno’s voice, in horror-film fashion, collapses over and over into a mad wobble. No one has more fun singing than this.

Here Come the Warm Jets is the very first album Eno made after escaping a crucial but too-limited role in a very young Roxy Music. I’ve heard from an irreproachable YouTube source that he was ecstatic upon leaving that band. And on Warm Jets and the several records that followed in the 1970s – Taking Tiger Mountain (by Strategy), Another Green World and Before and After Science – he’s clearly working with happy abandon (but also with care) to incorporate the oncoming rush of his ideas, both lyrical and musical, into his songs.

“Dead Finks Don’t Talk,” Warm Jets’ other nod to people not entirely pleasant, is extremely likable not only because Eno alights on the word “finks,” which surely belongs back in the vernacular. The song features spoken verses (“oh headless chicken, can those poor teeth take so much kicking”), a couple different silly voices, and put-downs that seem more for laughs than for wounding:

But these finks don’t dress too well

no discrimination

To be a zombie all the time

requires such dedication

~

To fall for Eno-in-the-‘70s in the two-thousand teens is to hear in his music so much of what so many have been listening to for the past 40 years. Some of Eno’s vocal tics are uncannily David Byrne-like, until one realizes it’s the other way around, as Here Come the Warm Jets came out four years prior to Talking Heads ‘77. His deadpan English-isms also serve as a handy bridge between Syd Barrett and his legions of emulators. David Bowie was clearly tuning in as Eno was tuning into Bowie, and the overt musical wackiness that surfaces occasionally on both Warm Jets and Taking Tiger Mountain call to mind They Might Be Giants and others who have, in all seriousness, made excellent ‘funny’ music.

These examples don’t quite plumb the point, however; the sights and sounds of Eno’s 1970s records are “modern” in the sense that they sound like they were cooked up yesterday. They’ve aged better than most of us. And they presage a mountain of music born over the subsequent 30+ years. While I’d assumed Eno’s principal influence had been on the famous records he produced for Bowie, Talking Heads and others you’ve heard of, his schooling of these acknowledged innovators, and therefore countless others, dated from well before he worked with them and flowed from the music that he himself had made. This won’t be news to everyone – particularly fans such as David Bowie and David Byrne – but those paying only partial attention (like me) might easily mistake ground broken by Eno for someone else’s plot of land.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hFLiKLoxWD8

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m3SjCzA71eM

~

My original intention was to write about Here Come the Warm Jets as well as Eno’s next three “vocal” albums of the ‘70s, the already mentioned Taking Tiger Mountain, Another Green World and Before and After Science. They are all great and if you are a fan you no doubt have your favorites. But the richness of Here Comes the Warm Jets, my initial Eno experience, keeps coming back on me. While the record may sound like the next 40 years of music, there are moments on it like nothing else I’ve encountered anywhere: The simmering insanity of “Driving Me Backwards” uncoils an astonishing vocal – really two vocals, Eno singing with himself – within a singular melody stretched taut to fit the tale as it lurches from strange to stranger: “Kids like me gotta be crazy,” he sings, and it’s true. “Meet my relations…grinning like facemasks,” and

I’ve found a sweetheart

Treats me good

Just like an arm chair

Or maybe it’s a “lawn chair.” Perhaps it doesn’t matter which kind of chair, perhaps it does.

The through-the-nose petulance of “Baby’s On Fire” (“baby’s on fi-yaaah”) evokes all the attitude of a sixth grader leaving a burning turd on a teacher’s doorstep. But it’s not a turd on fire, it’s baby. The song reserves three full minutes to allow Fripp’s guitar to go screeching this way and that, anyway it pleases – a thumb in the eye of radio programmers who might’ve considered playing this catchy romp about a woman who seems to actually be on fire, with no metaphor intended.

Photographers snip snap

Take your time she’s only burning

This kind of experience

Is necessary for her learning

As much fun as all this was, it was only the beginning. Brian Eno’s development, of course, stretched through the ‘70s, ‘80s, ‘90s, and ‘00s, and, as far as I know, continues. On Taking Tiger Mountain, the follow up to Warm Jets, the overflow of sounds and syntax was even harder to contain (check out “The Fat Lady of Limbourg”). Another Green World then edged into the ambient, wordless side of things while still offering some of Eno’s most charming songs. The fourth in this unassailable series, Before and After Science, had the pop song “Backwater,” something of a college radio hit, providing this tossed-of nod to mysticism:

If you follow the logistics

and heuristics

of the mystics

you will find

that their minds

rarely move in a line

Nor does Eno’s mind or music move in a line. After Before and After Science, one hears fewer and fewer words from Eno, who disappears into self-created aural worlds that have also changed the way life on earth sounds to anyone who’ll listen. Still, his ear for the lyrical rivals his rightly famous ear for everything else, as evidenced by the languorous long lines of “Here He Comes,” also from Before and After Science:

Here he comes:

The night is like a glove

and he’s floating like a dove

with his deep blue eyes

in the deep blue sky

Here he comes:

The boy who tried to vanish

to the future or past

is no longer alone

among the dragonflies

Who writes in this caressingly romantic fashion nowadays? Seeing a miracle in every arrival and departure, the song provides the room to come and go. How fortunate that I’ve come upon these records at this very point. Source documents have a way of surfacing when most needed; maybe that’s because they’re always needed. As the poet (Rilke) says, it’s praising that matters: find what you love and lift it to the heavens for others to love too. And don’t delay, because, as already noted, baby’s on fire.

What a beautifully written ode to one of modern music’s most revered pioneers. I discovered Eno as a teen growing up in the suburban backwoods of Calgary in the late seventies. Luckily my best friend at the time had an older brother who somehow received messages from space regarding the coolest music on the planet and would occasionally loan me an album… “here, go listen to this” gruffly.

Even though it was 40 years ago, I distinctly remember him handing me Here Come the Warm Jets and being enthralled by the British otherworldliness of the cover images and the title. Then listening to it the first time… something wonderful happened… a switch activated in my brain somewhere… or a door opened.

Another lp you might like is Lucky Lief and the Longships by Robert Calvert. Produced by Eno. Great record. Sort of a lost Eno lp.