IN 2006, I was a visual artist in San Francisco, living with my cat in a cozy rent-controlled apartment/art-studio in an up-and-coming part of town. At the time, I was obsessed with creating paintings on the glass of recycled windows with mixed media collages in the background, a technique that lent the artwork a three-dimensional effect. These painting-collages didn’t sell particularly well—they were bulky and the themes were too personal. The background of my painting about exes, for instance, featured a collage of jewelry, knickknacks and photos of happier times. And a piece about incarceration featured letters from loved ones in jail framed by bullet shells and cigarettes. Even so, these time-consuming pieces managed to get into several art galleries, much to my delight. In a city full of aspiring artists, it can be a challenge to even get your artwork seen by anyone at all.

As it happened, one of these galleries was visited by the elusive television scout, and soon, I was invited to be on a popular cable show about arts and crafts. Or at least I was told it was popular. I had stopped watching TV at the turn of the millennium so I’d never seen it myself, but a bunch of my pop-culture-savvy friends knew about it.

I’d been in the fine arts industry long enough to learn that there’s no such thing as a big break, but if a little bit of luck comes your way, you’ve got to milk it for all it’s worth. With that in mind, I looked into getting some beta blockers from my nurse friend to help manage my fear of public speaking—I was told they were good insurance against panic attacks. I shelved my distrust of entertainment industry slicksters and the mass-media web of lies (big boobs on skinny women; true love solving all a person’s problems; you know what I’m talking about). Warily but hopefully, I signed myself up.

The gig was unpaid, but I was promised national exposure. Like any person who makes a living off their art, “exposure” is kind of a trigger word for me—everybody who wants you to work for free promises this abstract, impossible-to-measure reward. ”Exposure” is not quite money, it’s not quite fame, and if you do enough free work, you start to realize it’s not quite anything. I mean, if [insert corporate name here] holds a logo design competition, can the winner expect to receive giant corporate bids for future projects? If [insert corporate name here] holds a T-shirt design contest, will the winner be launched into a cushy career, accomplishing the ever-elusive goal of making art for a living? (Spoiler alert: No.)

But still, television! It seemed to hold a different power than the routes I’d taken thus far. At that point, my clientele consisted mostly of urban techie liberals who shared my ideals and/or trademark pervy sense of humor. But what about the mosaic-making Midwestern housewife with a fetish for feminism and fart jokes? What of the Republican racecar driver with the closeted lust for crafts, cock and compassion? These were the people I desperately wanted to reach, and I wasn’t going to do that through any measly guerrilla art show or pop-up craft fair. If I really wanted to get myself out there, it seemed like national cable television was a good place to start.

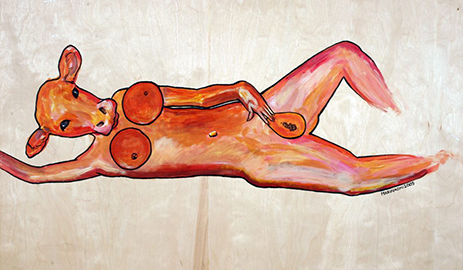

The show had some requests. For instance, they wanted art that was less controversial than what I was offering at the time. Although my artwork wasn’t particularly graphic, I tended to dabble in some pretty heavy themes while simultaneously putting a cute spin on them (like my porno pinup with the baby cow head symbolizing objectification and factory farming), so I thought I might slip a few by. But no, these guys wanted something family friendly. Something uncontroversial. I sketched out a bunch of ideas and was disappointed when they chose my least favorite, a painting-collage of a school of fish with a few suggestive elements they ended up taking out anyway.

Good-bye, phallic sturgeon.

So long, sexy anemones.

At that point I wondered if the exposure was even worth it. The piece they chose was less like art-that-will-change-the-world, and more like art-that-looks-pretty-on-the-mantlepiece. But I’d already said I’d do it and I’ve always prided myself on my reliability. I was in it, for better or for worse.

The undertaking turned out to be far more than I’d bargained for. I thought I’d be filmed for a couple hours as I explained to the camera how and why I do what I do. But with the way things were already going, I should have known that my preconceived notion would be shot to hell. What they actually wanted was to see me create one of these things—step by painstaking step. Considering that the process involved in assembling one of these art-beasts required extended drying time for each layer (and there were many), I found myself pondering the cruel sequence of events that led to my current conundrum. How would I shove a month’s worth of creation into a seven-minute segment? Ah, the magic of Hollywood was about to take place in my very own home!

I set to work. They gave me two months to create five duplicate, work-in-progress pieces, which meant I had to more than double my output. I was working nonstop, and making no money, which meant no quality time with friends, no boozing it up at art openings, and worst of all, no sex. My lovers were starved of my usual affection to the point of resentment—I was too poor to take my girlfriend out on the town, and too busy to do anything more than fuss with my boyfriend’s nether regions for a few distracting moments before I had to slap another layer onto my fish. (I’d like to note that my canoodling with multiple partners was due to the fact that I was nearing my sexual peak, it was San Francisco and I obtained informed consent from all parties involved). Anyway, my point is, I couldn’t really do anything but work on those passionless, family-friendly paintings. It was two months of living off savings and turning down paying work with the hope that this investment would somehow pay off in the long run.

It was around this time that I found a lump in my breast. This wasn’t my first lump. That formed when I was ten years old, a hard, painful disc swollen under my left nipple. As it increased in size, I cried myself to sleep each night, imagining how sad my parents would be at my funeral, but too afraid to actually tell them about it. The day I found a pea-sized lump in my other breast happened to be the same day we saw Terms of Endearment in the theater. (Spoiler alert #2: Debra Winger’s character dies of breast cancer.) That night I didn’t sleep at all, and the next morning I tearfully showed my mom what I’d discovered. She rushed me to the doctor, who took one look at my chest and broke out laughing. It wasn’t cancer, of course; it was puberty. I was so humiliated.

But now here I was in my thirties, a much more logical time to freak out. As a life-long hypochondriac, this was the moment I’d been waiting for, and with perfect timing, too, as I’d recently lost my health insurance in a breakup. For the first time in my life, I had no medical safety net. I knew that if I were to be diagnosed with cancer, I’d be blacklisted from ever getting insurance again. That’s how it worked, right? So I called up my last provider, I’ll call them “BS,” (for the sake of anonymity, of course) and tried to get it back. Since I had a break in my coverage, I had to go through an underwriting process so they could weed out those pesky cancer patients scamming them for free chemo (which, let’s face it, was essentially what I was doing—but how else would a starving artist pay for chemo?).

As one might expect, during this time I lost a lot of sleep. How could I have cancer? I’d quit smoking years ago, I never ate fast food, and I stayed away from toxic chemicals. And didn’t my hypochondria Karmically protect me from the Big C (I know that doesn’t make a lot of sense, but work with me here.)?

This existential insomnia had a silver lining though, as it gave me more time to work on my soul-less fish art for the TV show I didn’t want to go on.

As my deadline approached, the redundancy of creating multiple identical pieces gave me lots of time to mentally play out my tragic circumstances in variety of scenarios. I pictured the lump in my breast swelling, breaking off and slipping into my lymphatic system, traveling into my lungs, settling around my heart, sprouting tumors over the part of my brain that affects speech. I imagined how stupid I’d look on TV, stumbling over my words. Nation-wide, for everyone to see! Dying! As the date drew closer, I became more and more paralyzed with dread.

Every moment I could spare—when my glue was drying, when my hand was so cramped from holding a paintbrush that I absolutely had to take a break—I was on the phone with BS insurance, and my calls were more impotent than a steroidal wrestler. It seemed they’d transposed the numbers in my birthday back when I actually had insurance, throwing everything out of whack.

“How do I fix this?” I asked the woman on the phone.

I could hear her shrug indifferently on the other end of the line.

I tried it from every angle. On hold for twenty-minute stretches. Shoved aside. “Can I talk your manager?” I tried time and time again. I thought I was going to lose my mind. Then the glue would dry and I shifted focus, slathering another layer on what had become my closest companion.

Eventually, the day of the shoot came. My lame fish art was stacked in a pile in a corner, just barely dry. I’d reconfigured the place to make room for the lighting equipment and crew. I wore my favorite shirt despite knowing that it would undergo a terrible viscous death at the hands of paint and glue. Then I locked my poor cat in the kitchen to keep her from getting underfoot. Like the spreading disease that was taking over my body, this show had taken over my career, my life, and now my living space. I couldn’t wait for it to be over.

The crew arrived at my place at three o’clock. They were younger than I expected; a swarthy thirty-something guy in dark clothes, with long-but-tidy hair, and a couple of very young women who looked like former college math majors—friendly, but serious. The long-hair was the director, and he advised me on the finer details as the others got down to business setting up lights and covering logos on my art supplies with electrical tape. It didn’t take long before light banter revealed that these people were freelancers like me, hustling for their next gig, grabbing at every opportunity. They weren’t the schmoozy entertainment shysters I feared they would be. Still, I was nervous. Before we even started filming I could feel sweat pools forming under my armpits. Please don’t be visible. Please don’t be visible.

They filmed me doing the same things again and again, figuring out words and camera angles as we went. The long-hair coached me on how to talk. I had to do it in this unnatural way, as if nobody was there except for me and the viewer.

“Now I’m gonna make some art,” I said.

“I’m gonna use this marker to draw a fish,” I said.

I’d never improvised before, let alone on camera, but the long-hair helped me out. He fed me lines when I felt stumped, and I did my best to edit them on the fly so they didn’t completely humiliate me. Some of his suggestions made me cringe with prepackaged TV corniness. But it wasn’t long before fatigue got the best of me and, beaten down by the hot lights and nervousness, eventually I just parroted his lines.

“Now I’m gonna get a little messy,” he had me say as I lay down a tarp.

“Now I’m gonna add a little motion to my ocean.” I painted some waves.

The writer in me died a little with each repeated line.

After seven hours of filming, both the painting and collage were done, and I could see a light at the end of the tunnel. It was time to join them together. “Now I’m going to marry the two pieces,” I said, getting out some glue.

The long-hair directed: “Why don’t you say, ‘I think I hear wedding bells!’”

I could feel the lump in my breast force its way into my throat. What if I do have cancer? What if I die soon? This is the most public appearance I might ever make. Is this how I want to be remembered, regurgitating trite lines while showing off the blandest piece of artwork I’ve ever created?

I willed up what remained of my dignity and told him, “No. I will not say that.”

The long-hair gave me an irritated look, but he didn’t argue. We moved on.

After eight hours of filming, I was covered in flop sweat, paint and glue. Makeup was caked into every pore. But we were finally done. It was over! As soon as the crew left, I let my cat out of the kitchen and did a little dance. Now I could focus on cancer! I gleefully emailed my contact and asked if they could send me a tape of the show when it was ready. They weren’t allowed to do that, she said, but she’d be sure to let me know when it aired.

My head suddenly clear, I cancelled my insurance application with BS, and started fresh with a company that catered to the self-employed. Why hadn’t I done this before? With insurance in hand I went for a checkup. Both the mammogram and ultrasound affirmed that the lump was benign.

That night, for the first time in months, I got a proper night’s sleep.

Weeks later, a friend of mine caught the tail end of the episode I’d appeared on. I sent my television contact email after email, but apparently she wasn’t responding to me anymore. There was a time when this would have infuriated me, but I was done with feeling bad. The lump was benign.

Years later, I stumbled across my episode on the internet. Though happy I’d found it, I wasn’t particularly eager to watch it, as I was certain I came off as a total ass. But it wasn’t terrible. It wasn’t anything, in fact. Just another artist giving instructions on how to make boring art. In a seven-minute clip full of ludicrous sound bytes. It was over so fast, I was amazed that the bad taste was still in my mouth after all those years. Two months and eight hours for seven minutes of foolishness.

To this day, I haven’t gotten a thing from being on that show. Not one sale, not one commission, not even an email from an appreciative viewer. As for exposure? Sure, I exposed myself as a sell-out, forsaking my dignity and artistic spirit for the notion that I could reach out to people far and wide, skimming immortality at a very mortal moment. I got my exposure, but it certainly wasn’t what I’d bargained for.

But.

At least I didn’t have cancer.

Pingback: Exposed! – MariNaomi

Pingback: MariNaomi

Pingback: Forgive Yourself | Arts Collide Blog