SWANNANOWHERE

Me and Danny Creaseman are parked in his shit-brown Audi Fox up on the hill behind McDonald’s. We’ve got our seats all the way back so nobody can see us, and we’re taking hits off a little carved soapstone pipe. Dirtweed. Plastic Surgery Disasters tape in the deck on low. Danny leans up on his elbow and peers out the window. A few cars crisscross the asphalt out on the main road. It’s eleven p.m. and quiet. Danny carefully moves a .22 rifle into position and takes aim at the bulbous red head bobbing around in the breeze blowing through the parking lot below. He fires.

It had been down there for about a week. One day we came driving into Swannanoa—known locally as Swannanowhere—which is out on highway 70, a long curving road lined with strip malls and nail salons and cheap formed concrete apartment complexes with names that incorporated villa and court in an attempt to sound high class, and there he was, by the fenced-in playground area, legs crossed, two stories tall in his red and yellow suit and floppy shoes, his smile both openhearted and remote: a giant inflated plastic Ronald McDonald.

“Come in, come in,” he says, “or drive through. I will corrupt you. I will live in your bowels for a thousand years, an infernal tapeworm, gnawing away.”

I’m sure we wouldn’t have been able to articulate it at the time, but that giant clown symbolized all the fakery, all the gluttonous plasticity of the world we had inherited, and shooting at it indicated our rejection of that world. We were cynical young dudes, joined together by our status as outcasts. We weren’t achievers or jocks. We weren’t anything special. We listened to the Dead Kennedys, fucked up our clothes with markers, and sat in the back of the class talking cynical shit about everybody and everything. At night we got high and took potshots at the most obvious symbol of corporate America’s world dominance: Ronald McDonald.

FROM CHAOS TO COUTURE

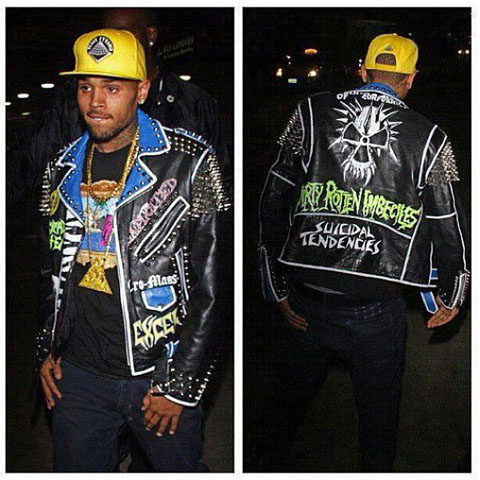

When prepubescent singing idol Justin Bieber started wearing a neon yellow cap studded with sharp metal spikes it nagged at the periphery of my consciousness. And then when pop rapper and unrepentant wife-beater Chris Brown started strutting around LA in a five-thousand dollar retro leather punk rock jacket with Suicidal Tendencies scrawled across the back (and a Corrosion of Conformity symbol, and Dirty Rotten Imbeciles, and the Exploited, among others) it irked.

But then it got worse. The Metropolitan Museum of Art held their 2013 Gala, PUNK: Chaos to Couture, and nobody made their own outfit. Luminaries like gazelles strode the red carpet in taffeta and lace: Beyoncé, in a flowing Givenchy ball gown, pattern reminiscent of bad tattoo flash, Kim Kardashian cocooned in upholstery fabric, Sarah Jessica Parker in a gilded headpiece a ‘la Marvin the Martian from Bugs Bunny. A lot of guys in plaid jackets and bow ties. Girls in blotchy raccoon mascara and fifty-thousand dollar diamond chokers.

Nothing even vaguely punk going on.

And then the litany of subcultural icons shrugging their shoulders at Urban Outfitters appropriation of their band’s names and logos to produce faux-DIY jackets and T-shirts grew longer by the day. Ian MacKaye of Minor Threat and Fugazi didn’t care if the company sold thirty-five dollar T-shirts with his band’s names on them. Penny Rimbaud didn’t care that they had recently introduced a leather jacket with Crass painted across the back, freehand, as if lovingly crafted by a fan.

They didn’t care. Why should I?

I’m not here to gripe about T-shirts and leather jackets. I’m here to gripe about the collective lapse in creativity these events suggest.

Not all that long ago, scrawling shit on other shit was a significant activity to me. As a bored kid in the back of class writing band names on my denim jacket in Sharpie—and eyeballs and spider webs and knives—I was expressing myself. And getting dizzy on fumes. And I was taking the mass-produced stuff of modern life and personalizing it. Nobody else had a jacket with band names/eyeballs/spider webs/knives like mine. I looked like a nightmare walking around in it. My mom was pissed off—ruining my clothes. But the jacket was unique. And it was mine. I moved in and said: “Hello. This is who I am. I am band names/spider webs/eyeballs/knives.”

I’m not saying everyone should be encouraged to express themselves. The pages of Etsy are replete with the calamities of self-expression. Not all can, and fewer should. And anyway individuality has long been a saleable commodity; looks have been cobbled together from the shelves of thrift stores for decades.

But I find it disturbing to think that now—somewhere deep in some (dim flickering green) fashion company warehouse—someone is painting Crass on the backs of jackets for minimum wage so that Urban Outfitters can sell them in their shops for hundreds of dollars. And it disturbs me that you can just go out and buy some do-it-yourself shit without having to bother with doing it yourself. It disturbs me that people want a painted punk rock jacket not because it’s something desirable in its own right—as a cultural curiosity, or as, God-forbid, folk art—but as a chic bit of wardrobe, an ironic reference.

In a world where self-expression seems more a matter of consumer choices than creativity, getting a little dizzy on Sharpie fumes doesn’t seem like such a bad thing to me.

FLYERS AND JACKETS

After graduation I moved to San Francisco to play in bands.

I was in twelve: Fuzzy Bunny, Grand Mandibles, Pupae, Strange Gods, Long Pig, The Phlegm Circus, Three Hail Marys, The Jackal Farm, Def Leprechaun, Chicken Diablo, Zimbo the Bush Pig, and The Trailer Park. Mostly punk bands, a couple of noise bands, an acoustic duo, and a weird experimental act with a woman who played the shopping cart. Some of these only survived one gig before disbanding. Others went on for years.

The longest running was Pupae, a sort of Butthole Surfers punk psychedelic act. We played gigs around the Bay Area, opening up for other bands mainly, playing the Punk Picnics held by the Gilman Street project, the dive bars in the Mission, some house parties. We were basically terrible, but we had our moments.

On Albion Street between Mission and Valencia at Sixteenth there was a flat where these hardcore kids lived. They were a small group of friends from Sarasota who had all come to San Francisco around the same time. You ran into a lot of groups like that in California—East Coast kids inevitably head west. These guys were hardcore skater dudes. They would ride their skateboards down the streets in V formation, looking dangerous and cool, open forties of Mickey’s Big Mouth in their hands, grab onto the backs of midtown buses and ride up the hills, let go at the crest and dive-bomb down the other side.

I dug their scene. Getting drunk and shaving each others’ heads, riding their skateboards around and blasting hardcore music. They went to punk shows and printed zines because that’s what you did: you made your own music, you made your own records, you made your own flyers for the gigs, you made our own paste from flour and water, you ran off a hundred copies and pasted the flyers to telephone poles all over town. You made zines to distribute, with reviews of shows and contact addresses of bands, you traveled around the country—hopping trains sometimes—to go to shows. You were linked into a vast network of punks in cities all along the circuit.

It was anti-clown: nothing mass-produced, nothing plastic, nothing factory-made. Everything was homemade, from the clothes to the flyers to the stickers, unsophisticated and honest.

LIFE

Life Sundance Stevenson was one of the Sarasota kids—a tiny madman, five feet tall, half Irish and half Tuscarora. We started the band Pupae together. He was into the hardcore scene like the rest of them, but he loved The Butthole Surfers and Metallica too. He played lead guitar kind of like Greg Ginn from Black Flag—chaotic atonal pyrotechnics. His dad was a homeless hippie who followed The Dead around for decades with just a backpack—train-hopping, hitching—so Life spent his formative years on the road, sleeping in ditches and scamming meals. It was an unstable upbringing for an unstable kid, and in his teens he went into a mental institution.

The reason I’m talking about him is because of his jackets, though. He’d started painting in the nut ward and found it therapeutic. The Albion gang wore a sort of punk uniform: jeans and Doc Martins, a denim vest with the sleeves cut off that you wore over a T-shirt or a leather jacket, biker-style. You would scribble all over the vest—band logos, anarchy symbols, skulls and shit—extreme dark imagery. But Life turned his jackets into tapestries.

He’d take any thrift-store jacket he could get his hands on and paint Bosch hellscapes all over the back, or like something out of Ralph Steadman, or Gibby Haynes, punk psychedelic phantasmagoria, symbols of mental illness: people limping around on bloody stumps, streets full of savage dogs, bodies falling into long tubes coiling like intestines, screaming heads with distorted faces, bats, bloodshot eyeballs pierced by syringes, depraved women by trashcans in alleys, telephone wires full of sinister birds, margins crowded with infantile sketches of dogs and cats, fucking and defecating. Blood seeping into everything.

It was disturbing shit. But there was an intense creativity behind it. Life could sit for hours drawing and painting instead of running around bugging everybody. I started drawing weirder shit myself.

SELLING OUT

In the early nineties a rumor went around that Black Flag’s Henry Rollins had starred in a Levi’s commercial. There was outraged debate over cream cheese, tomato, and red onion bagels in D.C. cafes. How could he do it? How could he suckle at the corporate tit? What about the truth and all that shit? It was like Dad had cheated on Mom, like the government had killed Kennedy. Just betrayal.

How could he do it, you ask? He needed cash. You can’t sleep in a trailer huffing gas your whole life. Black Flag had spent years on the road, and even as one of the most popular bands in the hardcore scene, they weren’t making any real money at it. It gets old. The Beats, the Hippies, the Punks—everybody sells out who’s lucky enough to sell out. The world runs on money.

And the corporations had been making inroads for years anyway—there’s a long tradition of record companies feeding off the art of the gutter. In the eighties, the culture-makers had improved their game, creating easily digestible music commodities like music videos and MTV, and a host of pre-made New Wave bands had taken to the airwaves.

Che Guevara silkscreened clothing became the must-have of nineties commercialized rebellion. Hang a Rage Against the Machine poster on your wall and your statement was made.

CULTURAL PLAGIARISM

I bought a cassette tape of Public Enemy’s It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back in 1988, the year it was released. I was amazed by the new technology of sampling. It was the first time I’d heard sound collages like that. The rise of the PC in the nineties brought sampling into the living room, and we saw a paradigm shift from instrument-based music creation to a new model of appropriation and collage. There was a host of court cases on the legality of sampling. The promoters of raves revolutionized the production of flyers and handbills, and bands started making their flyers in Photoshop instead of drawing them out by hand, appropriating and altering images lifted from online sources. They printed them out on Desk Jet printers. The results were astonishing. Suddenly everyone was capable of high-quality media manipulation.

Somewhere along the way appropriation and collage crossed over into outright theft, like for instance Lady Gaga’s recent lifting of the artwork of Salvador Dali for the design of her stage sets. The sets are not only influenced by Dali; they are Dali works, imagery taken directly from his paintings. It’s as if Ms. Gaga had pointed to a series of menu items—like in Internet programs where you upload a picture of yourself and try out different hairstyles to see which one you like best—and she got to a Dali painting and said: “That one. I want that one.” And her crew of engineers knocked it out.

Who better to steal ideas from than the most creative man of the twentieth century? He had a lot of them.

That’s what we do now. Find what you like, copy it, paste it. You are what you like. And as society sections off into camps of like, and like becomes the societal glue, the bellwether, the litmus test—three million likes for this or that give it legitimacy—it’s no longer about empirical truth but about popularity. Reality is reduced to a top-twenty list. Top one hundred ideas, filed away: we like dogs and cats, disadvantaged kids can cure cancer in science class . . . or just forming consensus: I too like bacon, I too like Target, I too like Miley Cyrus, and the list generates popularity, and they ARE RIGHT you know? Justin Bieber is nineteen and has released five albums. He’s published a book and made a movie. What about you? You can’t even get people to like that video of your vacation.

So. I blame sampling and personal computers and Lady Gaga.[1.Actually, Lady Gaga gets a pass from me for her support of transgendered teens.]

But I digress. There’s no use bitching about it. It was a few good years a long time ago. When the heroin came to Albion Street a cold fog settled down into the place. You’d go in and it would be just pasty-looking bodies laid out on futons, silent as corpses. Life died on a street corner a few years back. He descended deeper into alcohol and lost it just like his dad had. The Albion Street punks all moved on eventually. One is a carpenter, another a professor at Stanford, another guy just vanished. The dot-com boom came and went, and now you can only live in San Francisco if you hold seven jobs and sleep on a couch. Fashion designers make punk shit that costs thousands of dollars and assholes who never cared about the music lay out the cash. Musicians spend more time on their computers than in the garage. There’s a bunch of guys with stylized Mohicans, faces jammed into smart phones, waiting by the velvet ropes of dance clubs, hoping someone will usher them inside.

KIDS: SOME PRACTICAL ADVICE

Buy—or better yet steal—some magic markers and start scribbling shit on the back of your jacket. Focus on imagery that scares your parents. Start with a bloodshot eyeball, and behind that some gears with blood dripping, grinding, and off in the distance what looks like a troop of Nazis marching, and above that carrion birds wheeling . . .

KILL THE CLOWN

Danny and I take turns trying to take Ronald McDonald’s head off, but we can’t. It’s windy, but not bad enough to influence trajectory. We’re both decent shots, Danny more than me because he goes hunting, but the clown remains undamaged, just keeps bobbing back and forth in the breeze. We’d hoped to watch him pffff and slowly whither to the ground, to bring him down and—symbolically anyway, temporarily—bring down the corporate machine.

Later we descend the hill to get a closer look and we can hear the hum of the blower as we enter the lot. It’s a big industrial-sized blower housed in a little tent by Ronald’s ass. He isn’t actually a balloon like we’d thought, but—evidently to foil punctures of the sort we were hoping to inflict—he’s perforated all over the surface with thousands of tiny holes which the blower constantly forces air through. He’s in a constant state of inflation. There’s no bringing him down.

Woah this specific weblog is great i like examining your site content. Keep up the good paintings! You already know, a lot of persons are searching round due to this details, you may assistance these people enormously.

Thanks Prime Auto Buyers! I am been hopings to assistance people so! Thanks for good quick look! You know my paintings very dear to me so like faces of ancestor in the dark! Oftentimes the water flows back to the source! If I can assistance even one persons searching for these details I am completing! Thank again!

Amen brother, amen. As one of the millions of fucked up youth during the 80’s, I made many “artworks” on leather, cloth, pants, panties,etc. I was bored the other night and was googling the night away and wondered if any of my stuff was out there being adored. POW! There was my pride and joy battle jacket on display with the “Worn to be wild, the black leather jacket” exhibit at Seattle’s EMP. I was happy then pissed, because I never thought to sign anything, then happy again as my old age zen told me that nothing is yours anyway. I pawned it 28 years ago for $10. ……wonder what it’s worth now?

Makes me wonder where the hell everything is now. There’s some stuff I haven’t seen in ages. I didn’t get rid of it, it just went away . . .

I’m glad you at least got to see your jacket again. And you could always break in and steal it back. (Make a documentary!)

When I was eighteen or nineteen I burned all my shit. I thought it was sort of purging and Buddhist- all these objects define who I am and- like- keep me in the past- so I threw everything into a fifty-gallon oil drum and burned it. The smoke went up for two days, mainly because I burned my entire album collection too, including my prize cherry red vinyl Fresh Fruit for Rotting Vegetables (with poster), which I am now contemplating repurchasing on Ebay for 45 dollars . . . I think I got it for two bucks. Sheesh.