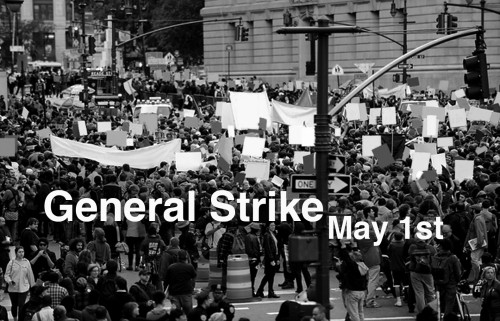

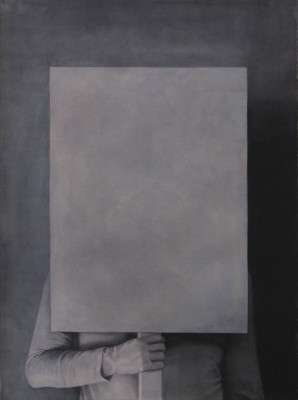

AT OCCUPY WALL STREET, Colleen Asper carried a blank placard. She’d set up a space in Zuccotti Park where people could make banners, but her own? Just an abstract shape. She couldn’t figure out what to say. People would ask her what she was holding or think she was being ironic or assume hers was a platonic shape or say, “Oh, that’s the logo for that new architecture firm.” But, it was the only thing she could carry, and those blank spaces keep coming back in her work. When the art collective 2-UP put together a newsprint zine, she included a photo of protesters carrying banners with the slogans whited-out. Then, there’s her watercolor of a man grasping an empty placard. At Zuccotti Park she was struck by how much the banners resembled painting canvases.

Colleen is a painter a writer can easily love. In fact, she’s so interested in words and writing you could call her a writer. And, she does write. She “loves” (her word) Tolstoy and Proust and Henry James and is, tantalizingly, working on a collaboration rewriting Henry James’s The Beast of the Jungle. Given my own interests (and struggles with) realism in fiction whilst writing realist fiction, her appreciation of James and Proust means a ton to me. She also paints in a realist style drawing on the Northern Renaissance including the slightly skewed, slightly off perspective of that tradition to question language and speech and the very act of writing from Google searches to speech bubbles.

I always think of the Northern Renaissance and its hyper-real, nearly forensic detail as “creepy realism” for the claustrophobic feel in the paintings. I also think there’s something about death in them. Maybe it’s all the dead Christs the era produced. Colleen thinks of it in terms of death too – as she puts it “of defiance of death, and that entire process of over-describing something (whether in fiction or painting) is akin to loving something so much you kill it and embalm it.”

This quality can give her paintings a kind of surreal sense particularly when she’s trying to paint a trompe l’oeil like that placard the man carries or her Rectangle With Gloves, where the rectangle and placard match the canvas. It gives her work a kind of Magritte effect (also because her technical skills are so damned good), but here she’s trying to create a one-to-one correspondence between the thing painted and the world. It ends up being spooky and suffused with the uncanny. It’s like Borges’ map or else this idea of the Platonic being everything everywhere, all the time, as if the represented is the representation. And, it goes back to the very issue of language and just what is used to speak or describe something, whether it’s in paint or words.

Being a painter now, however, is almost perverse. It’s far from cool. To get a sense of how uncool it is you only have to read a few lines of Jerry Saltz’s review of the New Museum’s Triennial where he laments the show’s “one obligatory painter,” and says, “Curators: Just once, please, I wish someone would take a stand and say, ‘I don’t like painting.’ … One token painter is worse than none.” Painting is so uncommon now, few artists have Asper’s skills. Still, there’s something fetishistic in the very act of painting in general, but even more so with hers and that intense level of detail she brings to each image. Each is incredibly labor intensive. I mean, one person for hours alone with a brush and canvas? That much time, that kind of relationship with brush and canvas and paint, suggests an act of great intimacy, because the labor is about the hand, and the work is so handmade. She wants to conflate, however, that handmade of the individual, laborious object with the anonymity of mass culture. One is full of authorship (or, at least, it seems to be), the other blank, mass.

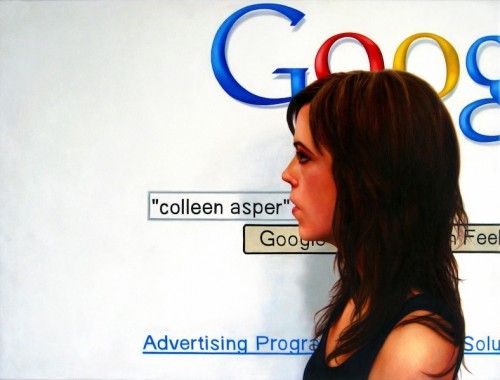

Take her Google portrait, say, which turns the idea of a self-portrait on its head. She calls it an existential painting. Colleen started off as a dancer before turning to art and explains, “The weird thing is as a painter if you paint yourself, people make all sorts of assumptions about the painting being you, either as autobiography or self expression, while a dancer is never the subject of her work. No one thinks her performance is about her.” So, Colleen wanted to paint herself where the painting was her but not about her. “Not,” as she put it in an interview a couple years ago, “accurate as a representation in any conventional sense.” In other words: existential. It acknowledged her existence, “without,” she says, “attributing a single quality to that existence.” Here the blank, though, is filled in. The Google search term is her own name….

Which brings me back to the blank posters. She was one of the early organizers of Occupy. The movement grew out of a reading group she’s in, but protest and politics aren’t really the subject of her work, not directly, at least, and those voids on the posters were the first places protest really entered her paintings. The blanks weren’t expressing doubt about the act of protest, but more about the conflation of placard and painting, and this larger interest in speech and language.

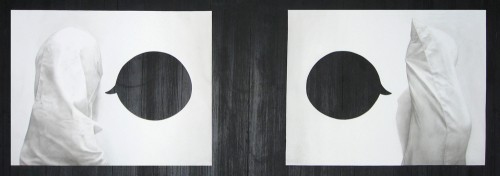

She painted a diptych of a cloaked person, each with an empty speech bubble. At first they said “yes” and “no,” but that wasn’t right, and they became blanks. She was thinking about Musil and The Man Without Qualities, where “the protagonist’s lack of qualities leaves only place and time to form his character.” She wanted to explore what it might be to be the woman without qualities, like her Google painting, say. Shown on the black floor of a gallery, the floor fit the absence, and for her the work doesn’t just have the two blanks but another, the one between the paintings too. In the journal Lacanian Ink she writes, “Not all silences are the same. There are three empty centers in this world. The empty space of the speaking subject, the empty space of the other, and the gap between them.” One person, another person, the space, the gap.

Meanwhile a video of hers has words fall from twin holes in a wall like a glory hole. The letters spill out and spell out a phrase. Like watching Jeopardy, you try to guess what they are. They came from a quote by St. Augustine about the idea that God experiences all words all at once all that the same time. That is the divine. Here, though, the divine is almost banal. The letters are “Looking Forward” which is both a temporal idea, eg: moving forward but also that commonplace sign off, “looking forward!” So, time, movement and nothingness all at once.

In all this thinking about speaking and writing she’s also investigated the labor and physical activity in writing. Which, dear readers who are writers, definitely makes her the artist for you. She does not see writing as some easy act. Talking about the Google painting, she has said, “It was extraordinarily labor intensive—I might spend all day painting and only finish four letters. At the same time I was also writing, so many times I would spend one day writing a couple pages and the next painting a few letters. This made me hypersensitive to the physical process of writing. Writing as an activity is deemed beside the point, the labor in writing is always described as cognitive. Yet how we recognize and value labor has tremendous political import, from the feminist movement’s reexamination of ‘woman’s work’ to more recent debates about the nature of immaterial labor.” This led to performance paintings of typing like the “Letter C” which is both funny and humbling and, writers, heroic.

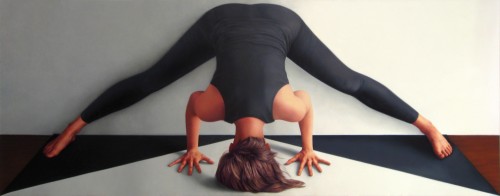

Now in her work, the physical is becoming the gesture. And maybe a language too. She’s started painting yoga poses. The mat conforms (just) to the limits of a canvas while the perspective is off a bit, as in the Northern Renaissance. The series started with a story she wrote about yoga, in the first person but not at all about her. The story is equal parts moving and funny and messy, describing how people fill up another space: this one the breath and blank mind you’re supposed to have in yoga. That space gets crammed full of all the wanderings you do in your head during a class. Looking at the paintings, the pose starts to seem almost its own language and communication system.

Indeed, she said in an interview with Michelle Grabner, “The work I make is not about abstracting experience. Design does that much more efficiently than art. Rather it’s about taking parts of experience that would otherwise be invisible that would other be an abstraction and making them concrete.”