BOBBY SEALE AND Huey Newton came to San Francisco State in the spring of ’67 to recruit at the same time Clorox, Kaiser and IBM came. The two men stood side by side, gave their spiel, their sign up sheets laid out in the back of the room. My roommates and I wore our hair natural and favored pea coats, hip ponchos and boots. But, I hesitated when my friends signed to join the Black Panther Party, remembering my civil servant mother’s warning about signing my name to radical causes.

While some came to call it the Summer of Love, for those of us in the belly of the beast-urban America, it was another long, hot summer. In August I joined.

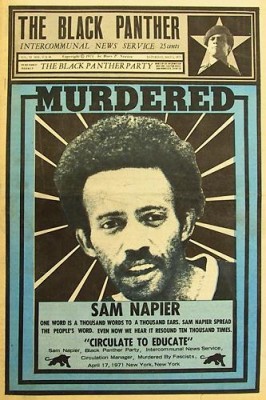

We five young women became the first wave of students from San Francisco State to join the Black Panther Party. We were referred to as sisters with skills. Evelyn handled finances; Janice became Bobby Seale’s scheduler; Betty managed the BPP office; and Jo Ann corralled the troops. I worked on the BPP Intercommunal Newspaper with Eldridge and Kathleen Cleaver.

Some of the first issues of the paper were laid out at The Black House. It’s no coincidence that that stately Victorian on Broderick St. was a prime gathering spot for poetry readings, jazz sets and political talks; poets, dancers, musicians, students, party people and the lumpen mixed and mingled for a time at this home of Eldridge Cleaver and poet-playwright Marvin X. The Black House unity didn’t last; the cultural nationalists, who advocated a black-only cultural milieu, and the militant Panthers, who welcomed alliances with radical whites, split.

The Panthers were creating a new language, what Jean-Paul Sartre calls superlanguage. Sartre calls it language distortion, a means by which the colonized deconstruct their oppression and reorder existence. Police became pigs; a deadly police raid became a reign of terror. We made the language, as Sartre identifies it, revolutionary and incantatory: Off the pigs. Power to the people. All power to the people. Free Huey.

Our gang of five affected policy and high-level decisions by virtue of our intense participation, outspokenness, our spacious Potomac St. flat which became a safe house, our connections to our families and communities in Oakland, Bayview/Hunters Point, the Sunset and Fillmore districts, and the state of Iowa where Janice grew up. Our parents and relatives provided money, housing, books, cars, meeting places, food and clothing to the party as documented by the FBI.

We also formed liaisons and romantic relationships with brothers in the party. From the upper echelon to the lumpen proletariat, we lived, slept, ate and cooked with the BPP, running up and down the state and the country, all of which was a natural development that resulted in many discussions on Potomac St. about the differences [and similarities] between brothers from the street and brothers on campus. We were the initial link between the campus and the party. Three of us married “brothers in the struggle” who also happened to be educated brothers. This is significant because our connections and intimacy [which some labeled promiscuity] connected brothers from the party with brothers from SF State. The BSU brothers like to talk about supplying the BPP with guns and money, but this bridge called my back supplied the people’s army with equal and greater provision.

When Huey was arrested and jailed in the shootout in November 1967, the paper overnight became an international organ, and the BPP an international sensation. To the world the party surfaced as the radical arm of the civil rights movement. At that point, my work stepped up with the paper. Donations poured into the office for the Free Huey movement. Police and FBI surveillance intensified. Six months later, the killing of Bobby Hutton and the shooting/jailing of Eldridge led to a meeting outside in Mosswood Park in Oakland, across the street from Kaiser Permanente Hospital. We met in the park because we didn’t want the FBI to hear the tape from Huey. On it, he reorganized the party, and to my surprise, appointed me editor-in-chief during Eldridge’s jail stay.

This changed all the dynamics. School became irrelevant. SF State had been indifferent and even hostile to Negro students for so long that the strongest sense of belonging had come from black sororities and fraternities. However, after going down South and participating in the Freedom Rides in the summer of 1966, a multiracial contingent of students returned to radicalize the campus. Those students developed the Tutorial Program at SF State into a community-based web of free after-school tutoring centers in the Mission, Fillmore and Potrero Hill. This campus program was a first concrete radicalization for many. My roommates and I tutored and ran several of the centers.

Many idealistic students in the Sixties dropped out and some devoted lives to the movement; by the time they returned to campus, many had changed their class affiliation. My friends and I dropped out and worked in the BPP full time. We eventually returned to campus too, armed, not only with actual weapons, but with a new consciousness about education, service, the poor, the police and the military, oppression, and civil and human rights. Our experience in the party helped us envision a viability in revitalizing and connecting to our community versus fleeing into the mainstream, corporate America or the professions as a distanced, glancing downward teacher or social worker. No matter our background, and all five of us came from two-parent, middle-class families, we became aware of the class contradictions in the American dream.

I saw Bobby Seale recently and had to remind him who I was by recalling the roommates. He said, quite sincerely, “Which one was my girlfriend?” I wasn’t insulted. After all, he was looking back 40 years, and we were far more than girlfriends.

Pingback: Fresh Ink: An Interview with Debut Novelist Judy Juanita + Book Giveaway - Natalia Sylvester

I have been surfing online more than 2 hours today, yet I

never found any interesting article like yours. It’s pretty worth enough for me.

In my opinion, if all web owners and bloggers made good content as you did, the web will be a lot more useful

than ever before.

Thanks. Glad you found this piece and liked it.

This is an outstanding piece that should be published much more widely, like in the Atlantic Monthly or New York Times Book Section I we, or Poets and Writers, or a number of places.

I transferred to SF State ( from Antioch in Ohio) and got my BA and MA in English there, from 1966 – 1976 while working full-time ( my MA was on the razor-sharp, grossly misunderstood writer Chester Himes.

I was an active participant in the 1968-1969 strike, a member of SDS and, during and after the strike, a member of the SF STATE English Students Union. One of our main goals was to change the racist curriculum that had two black writers and none by any other TWLF groups ( Native American, Latino American, Asian American)(or any writers from any continents except the United States and five European countries). AND YET……

I never knew about Sf State students in 1966 going on the Freedom Bus Rides. I vaguely heard about the Tutorial Programs; I was still in my own oblivion of being a very serious literature student and most of any extra time was reading the astounding BOOM of Latin American writers such as Miguel Angel Asturias of Guatamala (1967 NobelPrizeWinner), Carlos Fuentesand Juan Rulfo of Mexico, Jorge Amado of Brazl, Mario Vargas Llosa of Peru, and many others

I was also one of thousands infuriated by the assasinations of Malcolm X, Medgar Evers, Bobby Hutton, and Dr. King,not to mention the many rank and file assassinations of black and white civil rights workers in the south.

But it is very clear to me that part of the essence of the SF State Strike was the work done by our sisters in the tutorial programs because among the many successes of that program, it build a deep and lasting wide communist support for changing racism at SF State. And for that, Judy Juanita, her four friends and comrades in arms, and the entire tutorial program deserve our lasting gratitude and admiration.

I’ve learned quite a few important things by means of your post. I might also like to state that there will be a situation that you will obtain a loan and never need a cosigner such as a Fed Student Support Loan. But if you are getting that loan through a regular creditor then you need to be ready to have a cosigner ready to help you. The lenders can base that decision using a few factors but the biggest will be your credit worthiness. There are some loan companies that will as well look at your work history and decide based on this but in many instances it will hinge on your ranking.