Michael Bloomfield is what’s printed across the front of this box set. Not Mike, as he was usually known to friends, fellow musicians, and writers of liner notes. But Michael. Producer Al Kooper made that decision—Kooper, known always as Al, except to Michael, who called him Alan.

“We both called each other by our proper names, Alan and Michael, because that’s who we felt we were addressing,” Kooper writes in his “Producer’s Note.” Their propriety was a gesture of respect between two talented musicians, two friends, just as this career-spanning box set, released earlier this year by Legacy Recordings, is a gesture of respect and friendship, from Alan to Michael.

By way of an introduction, Kooper’s note lists 10 things he and Bloomfield had in common, like seeing Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers on their respective 15th birthdays, playing on Bob Dylan’s Highway 61 Revisited, and suffering from chronic insomnia. There’s one conspicuous event Kooper doesn’t include: backing an electrified Dylan at the ’65 Newport Folk Festival. (The scene as depicted in Todd Haynes’s film I’m Not There shows the band emptying machine guns into the crowd of folkies; you could say that Dylan gave the order but Bloomfield, amplified and snarling, pulled the trigger.) Newport was perhaps Kooper and Bloomfield’s most famous gig, and more would follow. They recorded some albums together. They did have a lot in common. But thinking about the commonalities leads us, inevitably, to the great and immutable distinction: Bloomfield’s been dead for 33 years. Just four years short of the 37 years he lived and breathed, until the final overdose. So this box set, more than a gesture of friendship, is also a monument, a sort of headstone Kooper chiseled into shape, dragged into the light, and sunk into the earth of the 21st-Century U.S.A., where Bloomfield’s name is still known to many but lost to obscurity for most, or never learned at all.

* * *

Here lies Michael Bloomfield. Who was he? Listen to the three discs, watch the documentary, and that will be sufficient. He was a hell of a guitar player. A white bluesman, when such a thing was still a novelty and perhaps a provocation. But Bloomfield was no stranger to the scene, no cultural interloper. He sat in with the kings of the Chicago blues, treated them with reverence, and won them over. Howlin’ Wolf introduced him as a friend from the suburbs. He babysat for Muddy Waters’s grandkids—that’s not a metaphor, it really happened. He was a blues fan who became a professional player but never lost his fan’s enthusiasm. That enthusiasm is baldly apparent on the earliest tracks included here, audition demos recorded for John Hammond in 1964 that might uncharitably be called “country blues impersonations.” But Bloomfield’s zeal electrifies his later material like the current running through his pickups: songs with The Paul Butterfield Blues Band and The Electric Flag, with Dylan and Muddy Waters and Janis Joplin, and others gathered from collaborations with Kooper and his own solo albums.

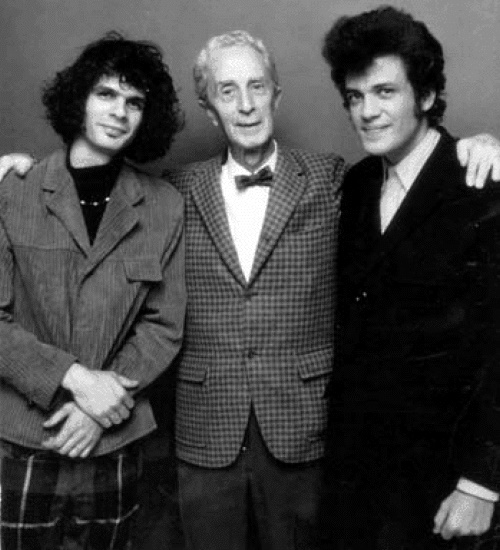

Who was he? Open the booklet that comes with this box set and check out the first photo. Al Kooper, Norman Rockwell, Mike Bloomfield. Yes, that Norman Rockwell, looking old and a little frail in his checkered blazer and bowtie, but grinning a grin that made me grin back. Loving it. Rockwell photographed the two musicians, and then painted them, and that painting became the cover of The Live Adventures of Mike Bloomfield and Al Kooper, released in 1969.

It’s like seeing Elvis with Nixon, these two: an odd juxtaposition, immediately jarring but, after a moment of reflection, weirdly appropriate. Rockwell-Bloomfield. As a duo, they don’t have as much in common as Bloomfield-Kooper, and I can’t match Kooper’s 10 points. But in the spirit of his “Producer’s Note,” here are five:

1) Rockwell’s work is archetypal 20th-Century Americana, in content and form. Looking back from over the rim of the 21st Century, Bloomfield appears likewise, in the content of his music (the electric blues, rock and roll, soul) and the form of his person (guitar hero, bluesman, integrationist, white appropriator, rock and roll casualty). Both mined the same rich Americana soil for tropes and images and experiences; both, in retrospect, are interred there. Whether that is to their detriment or benefit is up to you.

2) Neither artist searched for new frontiers or the next avant-garde; neither was especially motivated by a need to experiment with their art. Instead, they seized on American vernacular traditions, in illustration and music, and reshaped them according to their own idiosyncrasies. When Rockwell sat down to paint a Saturday Evening Post cover, he stuck to the conventions of the body of commercial illustration that preceded him—magazines, advertisements, government propaganda posters. But he could deploy those conventions, deepen them, nudge them, to create a scene like the weirdly enchanting Shuffleton’s Barbershop. When Bloomfield picked up a guitar to play “I’ve Got My Mojo Workin,’” or anything closely derived from the blues, he was repeating the basic motions of numberless players before him. But at his hand the notes are searing, desperate, combustive, as though he is using up the guitar in the process of playing it.

3) The art critic Dave Hickey wrote in his 1997 book Air Guitar that “people are regularly out of sync with the world in Rockwell’s pictures,” giving lie to the idea that Rockwell’s art is nothing but propaganda for some normative utopia. There’s strife, struggle, and heartache, but there’s also solace, maybe even redemption, in the very structure of the art. “The pictures always rhyme—and the faces rhyme and the bodies rhyme as well, in compositions so exquisitely tuned they seem to have always been there—as a good song seems to have been written forever,” Hickey wrote. And isn’t that just like the blues? A carrier of its own antidote in the salve of familiar rhythms and repetitions, the reassurance of the 1-4-5 chord progression, the songs that seem to have been written forever and will forever be written.

4) Rockwell and Bloomfield derive artistic power from two sources. One is virtuosity, sheer technical prowess. Rockwell was a master draftsman; Bloomfield a fluid and confident player. You can question the merits of their art, if you must, but not their ability to fashion it.

5) The other source of Rockwell and Bloomfield’s power is sincere emotional expression. Rockwell’s paintings, like Bloomfield’s blues, abhor cynicism, irony, and self-reflexive detachment from their subject matter. Instead they are engaged, sentimental, direct. Both artists could be playful—think of Rockwell’s Triple Self-Portrait or Bloomfield’s “I’m Glad I’m Jewish”—but they were also true-believers when it came to their respective art forms and the emotional content they aimed to deliver. It might sound strange, but maybe the impulse that led Rockwell to paint his Four Freedoms series, or all those Boy Scout paintings, is related to the impulse that led Bloomfield to the decision, conveyed to his friends, that he wouldn’t join Dylan’s permanent band if it meant giving up the blues. Which brings me again to this box set: From His Head to His Heart to His Hands is the title Alan Kooper chose for his monument to Michael Bloomfield. It’s a phrase that perfectly captures the style of Bloomfield’s playing—and what phrase better describes the artistic process of Norman (always Norman, never Norm) Rockwell?