WHEN I WAS a kid, I watched movies and TV looking for myself. It was important to find evidence of me within the scenes of Grease or Laverne & Shirley or Rambo. I lived in the Rust Belt, recession-ridden town of Moline, Illinois, and references to my hometown on the Big Screen were a kind of proof of my own relevance. In the John Belushi vehicle 1941, a random soldier says to the rough-and-tumble character played by Belushi, “I’m from Moline, Illinois,” to which Belushi replies, “Tough shit.” Despite the insult, I couldn’t have been happier to hear “Moline, Illinois” in a movie. Also, at the beginning of Nothing in Common, Tom Hanks says to someone, “From Davenport? One of the Quad Cities? Twice as good as the Twin Cities.” Moline, as one of the four doubly good Quad Cities, was a reason for pride. I existed.

I remember, during the Jerry Lewis Labor Day Telethon, my local news crew set up at South Park Mall in Moline in front of a giant plastic ball. If you tuned to Channel Four anytime during Labor Day weekend, you’d see newscasters talking in front of it, and people from my city dropping money into it. The prospect of me doing the same—of, in essence, making my television debut—was too much. I couldn’t handle so clearly crossing the line from this life to that life. I’d be too unequivocally there. It had to be harder than that.

Similar feelings continued into my adolescence, when I’d go to rock concerts and hope David Lee Roth or Gene Simmons would point at me in the crowd. “You. Yes, you. I’ve travelled far and wide, and I’ve never been so impressed by someone’s ability to rock. You should be up here with me. Maybe we could start a side project.” By the time I graduated high school, most of my fantasies revolved around getting on that stage, rocking for folks, someone like me suddenly becoming someone like Gene Simmons. In other words, someone else entirely.

No doubt plenty of others—the millions who attended rock concerts; bought albums, tapes and CDs; bought instruments and started making noise with them—were looking for signals from the world that they belonged, that their feelings were valid. Many, like me, became rock musicians. Others remained fans. For decades, the prominent stories about this subculture poked fun at us: This is Spinal Tap, Beavis & Butthead, Wayne’s World, the novel and movie High Fidelity. Coming off a decade like the eighties, when many mediocre talents in rock made millions from sycophantic fans, this segment of the music world was ripe for parody.

By and large, rock musicians and fans loved these caricatures. I certainly loved them. No one seemed to know better than us that we needed caricaturing, and what followed was a decade or two of representations of rock culture that were worthy of our laughter and pathos. As one musician said about This is Spinal Tap: “It’s both funny and painful at the same time.”

Despite all the send-ups, the choice of becoming a rock musician or fan isn’t entirely a frivolous one. Here’s one example of how that might be: If I had to narrow down the moment I knew I wanted to be a rock musician, it was when I was twelve and heard “Kashmir” by Led Zeppelin for the first time. Upon hearing its rumbling snare hits and majestic, violin-y march, I thought, “I want to go there.” I didn’t want to go to some region in India. I wanted to go to the music, that music. I wanted to take up residence in it somehow, intermingle with the guitars, bass and drums. I soon put it together that the path to this destination was to learn to play music, so I bought a bass guitar and started learning scales and songs.

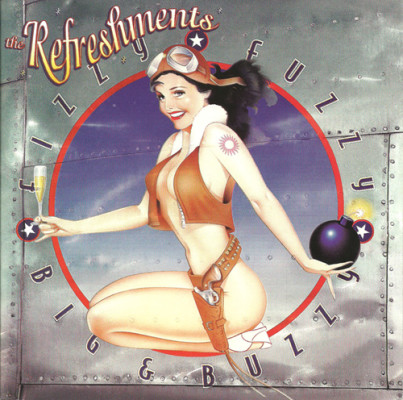

Before I knew it I was in a band called the Refreshments. We wrote our own songs, made records, played live, and generally tried to influence people with our music. I remember making our first album for Mercury Records in Los Angeles. One of the highlights was, after the final mix of each song, we’d take a cassette version of it out to someone’s car, pile in, pop it into the stereo, and listen. Ostensibly, we needed to hear what it sounded like through normal speakers, but we also wanted to hear how it stacked up to the hits of the day. One of the things we did was play the song, then quickly switch to a radio station and back, an “A/B” technique. I listened with rapt attention when we did this. Had I arrived? Was I there?

Many of our fans thought so, and quite a few of them liked our songs so much they bought instruments and tried to learn to play them. To be clear, no one ever confused my band with Led Zeppelin, but some heard our stuff the way I heard “Kashmir” on that fateful day. Our band changed their lives just like Led Zeppelin had changed mine.

So what happened here? I feel there’s a passing down from one generation to the next of a kind of music, which contains our sense of what’s beautiful, our conflicts, our voices, our ideas—in a word, us. Despite the pomp and greed of earlier eras of rock music, we still managed to create a tradition, and I dare say there’s something dignified in that. I offer every story and screenplay I write as an example of how a life in rock need not be entirely about driving motorcycles through hotel lobbies and snorting cocaine off hookers’ breasts. It comes from the same place any calling comes from: the will to bring to life that which within us seems too important to ignore.

In 2014, with many Boomers now on Medicare and people my age with jobs, kids and mortgages, a deeper tradition of rock storytelling is well underway. Recent films like Crazy Heart and Inside Llewyn Davis, documentaries like The Story of Anvil and Searching for Sugarman, and novels like Banned for Life and Stone Arabia portray rock-tinged characters who aren’t just jokes. Are these stories fun? Of course. But just as importantly, they’re about characters who follow their passion for music and deal with where that journey gets them, sometimes with genuine dignity. And all I can think is, Yes, that’s me, right there in the story. Just like anybody else.