HERE’S TO Pearl Harbor Day.

Remembering Pearl Harbor Day at 82 from the perspective of a nine-year-old, let me begin with this suggestion. As our entry into World War II, it galvanized this country like no other war we have fought since. Maybe that’s what Navy veteran and Pearl Harbor survivor Clifton Dohrman had in mind when he said this:

We had to have everything replaced, and if the American civilians hadn’t jumped on the bandwagon, we would never have won that war. They replaced all of the planes that we lost, rebuilt new ships, new ammunition plants, and everybody in America went to work. To me that was the highlight.

With my vivid recall of that fateful day and its immediate aftermath, that’s what I like to think. In fact, civilian accomplishments lesser than rebuilding ships and replacing planes helped win the war, too. And so did a solid spirit of national purpose. What stirs me most as I remember Pearl Harbor is how quickly the country mobilized for what we immediately called “The War Effort,” and how broadly folks participated.

It commenced for me at three o’clock that Sunday afternoon, when my dad appeared while I was sledding with my brother and two friends down a Pittsburgh hillside to tell us what he had just heard on the radio. The Japanese planes had just bombed Pearl Harbor in a place called Hawaii. “The country’s at war, boys,” he said stoutly.

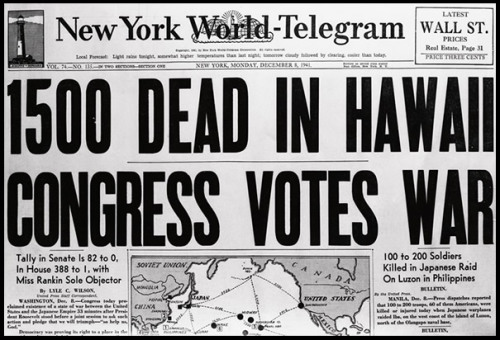

Which took me by surprise at first. Then learning to read the newspaper on my own, I recalled a headline that very morning proclaiming Japan had signed a peace treaty with the U.S., supposedly reducing mounting tension in a world already tense with war in Europe. We ceased our play and circled our sleds at the foot of that slope, sat on them triumphantly, and insisted we would beat the Japs, ready to go to war ourselves.

We were too young for that, of course, but almost immediately we were being drawn into a whirlwind of civilian activity that seemed to involve everyone, including kids. Within weeks we were canvassing the neighborhood with wagons on what was being called scrap drives, collecting old pots and pans, discarded garden tools, toasters and electric fans that no longer worked, and especially things made of cast iron, whether a large, overused Dutch oven or a tiny toy car. Even a miniature rubber tire from one of those was salvaged, along with modest wads of tin foil and randomly gathered old nuts and bolts. All of which we hauled to the local school yard, where it was collected and taken to some larger pickup point.

We were arbitrarily put into groups competing for the distinction of accumulating the biggest pile. I have a clear memory of cheering alongside others as a teammate boosted our pile with yet another wagonload. The metal and rubber would be reprocessed, we understood, as planes and ships or weapons and ammunition. Paper and cardboard were similarly salvaged and used to make cartons for packaging supplies being shipped to soldiers. No item was too small to matter, no schoolboy too small to pitch in.

For kids it all added up to a climate of raucous excitement. Within weeks of our entry into the war, draft lists were being displayed in post offices and at selected store fronts to determine who would be inducted. We boys were being offered nickels and dimes by fathers and neighbors to walk to local business districts and locate the name of a dad or an uncle with his assigned draft number. There we would elbow our way through other squirming kids gathered there to get close enough to thumb through a list and match a specific name with a number.

Just as swiftly, neighborhoods were being organized into civil defense units. Each city block was assigned a trained air-raid warden whose job was to patrol during a drill and blow a warning whistle at any house where even a sliver of light breached a darkened window whenever sirens blasted across town during a practice raid. Most exciting for us kids was that we could sign on as junior wardens and tag along through near-total darkness, eyes peeled for telltale strips of light. What adventure that was.

Around that time the grassroots campaign gained momentum to finance the war effort with the sale of war bonds, each costing $18.75, and set to mature in ten years for $25. That was a lot of money then, of course, but kids were able to take quarters to school on a designated day each week to purchase individual stamps to paste into their own booklets, where 75 could be redeemed as a bond of their own—an incentive to earn extra change performing chores around the house like stoking the furnace or shoveling snow now that fathers or big brothers were away.

With rationing, each family was issued a ration book allocating only so much sugar per week whether rich or poor, so many eggs, so many canned goods, bars of soap, pounds of meat, and so forth. Like our parents, we were learning to be cautious consumers; the value of food was now being reckoned in terms of a widely shared war effort, not just monetarily. While ration stamps were not actually issued for gum and candy, Hershey bars and Milky Ways had became hard to come by, as were five-cent packets of Wrigley’s Spearmint and Juicy Fruit gum, nickel tubes of Life Savers, and even penny blocks of Fleer’s Double Bubble. So that soldiers could have them, we were told, in what became personal shortage for us boys and girls. Shared sacrifice was a rallying cry for young and old alike.

Routinely, we went by trolley downtown to the Baltimore and Ohio train station, where draftees were marched through the lobby and boarded on trains for induction. Generally held on a Saturday or a Sunday so that entire families could participate, the occasion was as festive as it was somber. Red-white-and-blue bunting hung everywhere as a band played, a Congressman or a Senator gave a speech, and a local clergyman offered a benediction. Wives and kids and sweethearts kept astride as far as they were permitted, kissing and crying and waving as their men were being marched away. Such excursions accustomed us to mighty crowds, which also helped make it everyone’s war. And it became more specifically ours, as we kids clamored through the crowd, seeking uniformed soldiers to shake hands with or pat on the back.

The Pearl Harbor attack enlarged the world for us youngsters as could no event other event I can imagine. Recently we may have felt a touch of that with 9/11, but that shared spirit vanished all too quickly, maybe because there was no call to sacrifice, or to extend our horizon beyond the limits of consumerism. It was different back then, or so I like to think. Real geography transcended the schoolbook variety as our vocabulary of place names grew cosmopolitan. We learned to read maps and could locate Bataan and Corregidor in the Pacific, places across the Atlantic like North Africa and Scandinavia.

Without my fully realizing it at the time, we were being summoned to understand as well as vanquish our enemy. Soon after the war began, I recall, the government issued an appeal to learn Japanese, which few Americans then knew. Roosevelt summoned the noted anthropologist Ruth Benedict to study the culture, which resulted in the now famous landmark ethnographic work, The Chrysanthemum and the Sword. Without my being aware of it then, the country was being weaned away from its former isolationist remove from the so called Old World.

As I now recognize, the attack on Peal Harbor began a process of bringing us together that has continued by fits and starts ever since. Ethnic divisions began to narrow. There was something larger going on here. We were learning to be Americans together. Slurs not uncommonly used in the immigrant world I grew up in as a first generation American member of a minority began to disappear. Unflattering epithets like hunky and dago and kyke and wop—terms I now wince to repeat—began to dissolve as the war quickly became everyone’s.

I remember in particular a movie short, “The House I Live In,” starring Frank Sinatra, that circulated widely during the war years. It begins in a crowded urban neighborhood where a gang of kids, rocks in hand and fists tightened, is clamoring after one in solitary flight. Happening along and seeing the melee, Sinatra asks, “What’s going on, boys?” and one of them blurts out in response, “He’s a dirty. . . .” But right there, before the unflattering label is uttered, Frank interrupts, reminding them that we’re all Americans united in a common effort, sharing the same house as one family, then breaks into a song that begins with the movie’s title.

I forget how the lyrics go, but I remember the melody clearly and the clarity of his voice. I remember as well seeing it replayed again and again in theater after theater with one feature or another. Notably, it was structured as a message of tolerance directed to kids, who I now realize were being conditioned to see themselves bonded in the pursuit of victory.

That purpose, I now believe, was forged by the Great War, beginning on what Roosevelt then called a “day of infamy.” Infamy yes, but only to a limit, because it did bring us together, especially we children who while too young to join the army or navy or marines were drawn into the war effort fully together. By contrast Korea drew indifference while Vietnam divided us, and subsequent wars were undertaken with sustained inattention and aroused intense political partisanship. Furthermore, they were wars fought by professional volunteers, not draftees drawn from all sectors of society, which helped civilians remain disengaged.

I don’t say that to find fault, but merely to observe that World War II was all of ours, largely because it began for us with a surprise attack that changed the world, not just for four sledding boys, but all their contemporaries. We were all equally threatened and equally encouraged to meet that threat together. That is why, with the perspective I have acquired over the years, I am inclined to say, here’s to Pearl Harbor. For mine is a boyhood that with that one event instilled a brand of patriotism open to all. I even like to think that with the jolt of Pearl Harbor began the momentum that ultimately integrated the military, followed by the civil rights movement, the women’s movement, gay rights, and a lasting awareness that a fully galvanized America is an ongoing process that lives today in the struggle for immigration reform.

Granted, I was a mere boy then, given to boyish simplifying, as yet unable to grasp subtleties or to understand the nuances of controversy. Senator Joseph McCarthy and the Cold War were not yet on my horizon—I was too busy learning to look west toward the Pacific and eastward at Europe and North Africa to join the march to victory in a boy’s way. There was as yet no domino theory which drove the kind of adventurism that some say Korea and Vietnam instigated. So I grant you that everything I say here today comes from a boy’s perspective, tinctured by nostalgia. Just the same, what a boyhood it was. I would wish one like that for my grandchildren—but without the ravages of war.