“BE A MAN!” takes its title from the commonplace imperative you often hear on morning chat shows and advice columns. It brings to mind those empowerment phrases: “Grow a pair,” “man up” and “show some balls” which reaffirm a narrow corporeal idea of masculinity, even though we all know it ain’t nothing but a construct. This small but diverse show of photography and sculpture at Sumarria Lunn in London manages to undermine any straightforward notion of masculinity, asking instead, “how can you be a man” when there’s no way of circumscribing what it actually involves.

The curators have selected work from the 1920s to contemporary Britain, which veers from portraiture to collage. One common theme that connects the choices is boxing, the continuation of which, in these safety-conscious times, Joyce Carol Oates once described as “a celebration of the lost religion of masculinity all the more trenchant for its being lost.” Last year women’s boxing qualified as an Olympic sport for the first time ever (despite its long history), giving the exhibition a slightly elegiac feel. Photographer Mahtab Hussain’s series, “Building Desire,” shows young British Pakistani Muslim men topless, hair styled, bodies sculpted, against the background of the gym. “Beard, Abs, and White T-Shirt” has a young man standing side-on, open-mouthed, looking at the camera, stretching the item of clothing in his hands, as if to emphasize his bare-chestedness. In “Shemagh, Beard and Bling,” the thickness of the guy’s neck, his bulk, is offset by the elegant throw of the shemagh around his shoulders. One of the portraits features another bearded man with what resembles a prison tattoo – two tears – under his left eye.

Mahtab Hussain, "Building Desire: String Vest, Two Tears" Courtesy of Mahtab Hussain/Sumarria Lunn Gallery

Hussain’s portraits are the most striking works here, because of his refusal to explain or depict his subjects’ lives beyond bodybuilding. Are they religious? Bodybuilding’s Christian roots possibly account for its observance of ritual, diet and self-control (though Christian bodybuilding is still a thing, as pecs can apparently make you a better witness for Christ). What was termed “Muscular Christianity” developed in the 19th century, a perfect consolidation of fears about poor working class health, running an empire at its productive peak and the obsolescence threatened by rapid industrialization. Hussain’s work explores how a common identity is built in the gym, but the men here escape any boxing in. They tout their gang affiliations as easily as their religious ones, while the individual portraits – with the men flirtatiously soliciting the viewer’s attention, or daring him/her to judge – make it impossible to read them as a group.

Strangely, it looks like such a lonely pastime, despite the homosocial vibe of the gym. But Hussain’s subjects clearly find masculinity, the conventional idea of masculinity, empowering. The series also sparks off another recurring theme of the exhibition: what does it mean when the conventions of masculinity are appropriated by a disadvantaged group?

Claude Cahun’s “In Training, Don’t Kiss Me” sparkles with humor as we try to make sense of it. The artist, once known as Lucy Schwob, appears in boxer’s shorts, with paint exaggerating her nipples, lips and cheeks. The training could allude to her performance as a woman, or as a man or to her transgender identity. Her temporary markings make the young British men’s invocations to masculinity, through tattoos and violent pet dogs, look similarly absurd.

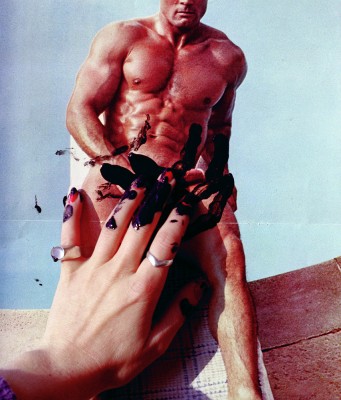

Alexis Hunter’s photographs were ripped down by security guards when they were first exhibited in Belfast, in 1978. In the two pictures taken from that series titled “Masculinisation of Society,” we see a pornographic photo of a nude man splattered with black ink by a feminine-looking hand. The head of the man is chopped off, in order to make him appear even more vulnerable, as objectified as any woman in a fashion magazine. It’s hard to work out what offended the guards – was it the fact that the man in question has his penis in his hand or is it the violence with which the other viewer’s (the one in the picture) hand graffitis the lower half of his body?

Alexis Hunter, "Approach to Fear XVII: Masculinisation of Society Series" (1977) Courtesy of Alexis Hunter/Sumarria Lunn Gallery

The series still feels powerful, in its rawness, except that we have many ways of appropriating this kind of hypermasculine imagery now. For some reason, I thought of the tumblr Feminist Ryan Gosling where images of him being as adorable as an actual gosling are juxtaposed with feminist sweet nothings like “Hey girl, yes means yes.” I also thought about how the actor’s elevation to the smart woman’s fap material has coincided with his most violent brooding roles, where he only seems to stop shooting other men in order to monosyllabically hug a baby. It seems like the power in Hunter’s work derives from the black and whiteness of its vintage and uncomplicated politics.

Scottish duo Littlewhitehead specialize in implicating the viewer, by making us stand over or behind their (normally) life-size figures. The Overman is a miniature boxer in his dressing gown who stares across the gallery, knee-high, with a sad defeated expression. Like their installation “It happened in the corner…” which sees life-size wax figures in hoodies huddled together, the piece here is about men who can’t look you in the eye. Our pity for them implicates us into the idea of a “crisis” in masculinity.

Hank Willis Thomas’s text series riffs on the civil rights protestors placards that declared “I am a man!” appealing to a universal definition of the term “man.” More than forty years after the strike by 1300 black sanitation workers in Memphis, Thomas questions the assumptions in that phrase – stating uncertainly “A man I am,” using the imperative “Be A Man” and the comic masculine roar of “I am man.” The phrase was again appropriated by protestors during the Arab Spring, and described by commentators such as Thomas Friedman as a summing up of the movement. Like Cahun’s playful portraits, Willis’s undoing of the statement shows us how fragile the idea of a universal man was from the beginning, though the separate frames of the pictures suggest it is too difficult to reconcile all these different positions.

The curators seem to suggest that there are multiple ways of being a man, even though the title of the exhibition points to how so much of our language of empowerment is gendered. While it’s a small exhibition, it feels rich and provocative, making us question our own assumptions about how and what masculinity should be.