IT STARTED WITH Althusser and ended in Las Vegas. In between came looking for love in all the wrong places – like a strip club. He the customer, me the stripper.

It was summer when Peter first came in. This I know not by the temperature or humidity but by his tan poplin suit. Strip bars don’t have seasons, just frigid A/C and skimpy outfits regardless of the weather. He wore a bow tie and round glasses both of which set him apart from the usual customers, as did his recognition of the irony in my own outfit, a school uniform.

It was just before my shift at a table-dancing establishment near Wall Street (and oddly across the street from the IRS). Getting in a few dances before I officially started was my ritual to ensure a good night. I needed a clutch of bills in my garter as a talisman. I stripped for him and had a drink, an expensive Diet Coke with lemon. He joked about the cost of that lemon, and we discovered we went to the same university for graduate school a couple decades apart. He studied architecture and I art history. I told him about dropping out of my PhD program that year because the art world was too conservative. To which, one professor had called me too unteachable.

Peter laughed. “They didn’t much like me there either. They didn’t appreciate an architect who didn’t believe in building buildings. I was too much a Marxist.”

We compared notes on school, disillusionment and Marxists until he asked who my favorite was. “Althusser,” I quipped, “though he was institutionalized.” I told him I liked Althusser’s pessimism – “the only Marxist who didn’t believe radical change was possible” – and before Peter had a chance to pay me, let alone a chance to ask, I got up to dance.

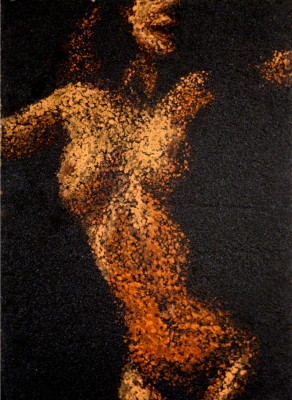

Shoulders shimmying, hips rolling, I quoted Das Kapital. “The commodity fetish,” I chanted to the music, “is a strange and mysterious thing.” (The music itself was about Daisy Dukes or some other standard strip club fare ca. the early 90s.) “As soon as it steps forth as a commodity, it’s changed into something transcendent.” (Cue slithering from a piece of clothing.) “Whence then arises the enigmatical character of the product of labor so soon as it assumed the form of commodities?” (Shake rear and drape another piece of my outfit around his shoulders.) “Clearly from the thing itself. A commodity is a mysterious thing.”

He laughed and stood and clapped. People stared, and he handed me a hundred dollars for three minutes of gyrating. The commodity fetish is indeed mysterious. Part of my problem with stripping was the ephemeral nature of the exchange itself. I often wondered what men were paying for and felt guilty for selling the idea of sex – the image of availability – but nothing real or actual. I felt like I was tricking the customers.

Now I’m not naïve enough to believe a guy ends up in a strip club just wanting a drink. Any bar can take care of that need. No, it’s lust or some approximation of that. For Peter too. He was lonely, living in exile in Virginia where he’d moved back home to care for his elderly father. Here on a rare night alone in New York he ended up in the club and not at the Vietnamese restaurant he’d set out for.

Peter came back again the next night and again and again each time he was in the city. He told me about his father, the loneliness of living in a small town, his struggle with his client down the street from the club, and how hard it was to hold onto his career from afar. I told him about my boyfriend, who I normally kept a secret from customers. It was bad for tips and that image of eternal availability we strippers sold. I also talked about my longing to be a writer. My anxiety was as heavy and unsubtle as most of the dancers’ perfumes. He listened sympathetically, and even asked why I was dancing. I gave him a line about playing with the tropes of sexuality or something equally high-minded sounding but not exactly true.

What I didn’t understand then was that the club gave me a place to explore being sexy without any expectation of sex. I also wanted men to see beyond the image of me on stage and value me as a person. Whether my customers could was a test of them, or myself, only I didn’t want these relationships to leave the club. I thought what happened there had nothing to do with my life, and I avoided the men outside of work. Unlike other girls who’d have lunch or dinner and go shopping with their favorites, I was terrified of the club seeping into my private life. Until one night Peter came in and announced he couldn’t do this anymore. He knew me too well. We both saw the inherent contradiction in his decision. If he didn’t know me, it was fine to watch me strip but not now, not if there was some kind of genuine intimacy involved. It was too personal.

When he told me this, I felt a dull ache in my chest that I’d never see him again. Before he left though, I gave him my phone number – something I’d never done before. Men often pleaded for it, and I’d placate them with a line and a lie, telling them the club wouldn’t let us give out our numbers but if they gave me theirs, I’d call. Hence, the many business cards I was handed with scrawled digits and endearments – a collection I have to this day.

Three months later I quit and the boyfriend and I broke up. I called Peter who let me talk on and on about my hurt heart. Soon we tried our hand at dating – though the idea made me nervous. When I was dancing, I’d wanted my customers to transcend the role of “strip-club guy.” I was craving something authentic in the club, but now outside of it, crossing that line felt impossible because my expectations were still a stripper’s. In the club girls had bragged about all the stuff they got men to buy them, and I tried to tell myself that was what I wanted from Peter – stuff.

Then, he suggested five days in Vegas. It was the perfect trip for us – slightly seedy and high minded. His invitation came with a copy of Learning From Las Vegas. His sister said going was a bad idea, his friends (all male) that it was a good one. After all, what could be better than Las Vegas with an ex-stripper?

Many things.

For starters our expectations were at odds. Peter thought he was going away with the woman he was dating, and I with a customer even though I’d never talked about our dating in those terms. He also needed time off from his life as a caregiver. He needed someone to be as understanding of him as he’d been of me.

In Vegas we went to the bone yard, a kind of neon graveyard where the city’s largest sign manufacturer kept old signs. Here, amidst Aladdin’s Lamp, The Silver Slipper’s ten-foot high shoe and a few “Girls, Girls, Girls,” he asked the manager if losing these landmarks from their place on the Strip upset him. The manager said never. “If it’s not growing or changing, it’s dying.” An unsentimental Vegas philosophy I took to heart as if it applied to Peter and me. Peter was kind and caring while I was cold and mechanical as if we were still in the club. In fact, probably more so. We certainly weren’t growing or changing at all.

I’d duck his embraces. I was late to bed and early to rise, and once I did, I’d go bounding down to the hotel gym. He asked what was wrong. I fobbed him off with my worries about work. The town was all about signs writ large only I couldn’t read my own. I was scared of what being here with him said about me. The club had given me a safe place to act out defined roles – and even transcend them – only here we’d slipped free from the moorings, and despite the fake landscape all around us, this was all too real for me. Turns out I was better at miming seduction and intimacy than actually engaging in either of them.

In Las Vegas I’d thought I wouldn’t have to address my conflicting feelings about dating a customer. I’d hoped to keep what I was doing here from everyone I knew – even myself. Yet somehow in this baroque panorama plunked down in a desert, I ran smack dab into my life from back home. Someone should have said, “What happens in the real world shouldn’t turn up in Vegas.”

In an underground passage linking one crazy attraction with smoke and fire to another with fireworks and smoke we ran into a friend of mine and his willowy girlfriend. I tried to hide Peter, rushing to the couple and shouldering him out of our group. Here in this tunnel with its buzzing lights and stale smell I was ashamed to be seen with this guy more than a generation older than me and kinder than most men I knew. I didn’t introduce him. He had to thrust his hand forward and do that himself. Afterward, the hurt obvious in his voice, he said I should go off with my friends.

The next day I came back from the gym and his bags were packed. That’s when we finally broke free from the confines of the club and its expectations. He said he was going. He said he didn’t want to keep trying this with me anymore. It was obvious that I didn’t want him. We fought then talked. My chest ached. I kept swallowing. I hurt and knew I’d hurt him even more than myself. I cried. He said he wanted to. At that moment I felt closer to him than I had the entire trip, the entire time I’d known him. I finally saw what he’d been offering me. It was something genuine, something authentic, only I’d realized too late.

That night he didn’t leave. We slept in separate beds, and he started calling me “pal.” The endearment was heartfelt, saddening, three little letters and in them all I hadn’t let in.