ON A COOL, cool evening in late June, Alex Rodriguez continued a post-PED renaissance season by sending his 3,000th career hit, a home run no less, into the stands of Yankee Stadium. Pandemonium ensued, as most of the crowd went absolutely nuts cheering the feat—so nuts, in fact, that the ball itself bounced from one seat down to the footing of another, temporarily unnoticed.

Unnoticed, that is, by all but one person—someone whose life’s trajectory had been leaning toward this moment for years. Zack Hample, who had come to the game alone, swerved without a peep through the madding crowd from two or three rows up, grabbed the ball, and held it close to his chest. He knew the cameras would be on him soon enough, once the glow of the hit itself had faded and A-Rod had rounded the bases.

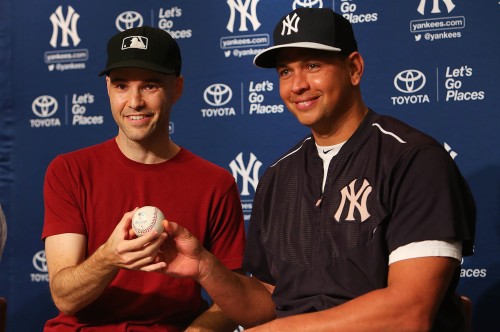

And soon they were. They zoomed in on him as he held the ball up, yelling and pointing at it, and they followed him as he made his way out of the stands and into the underbelly of the stadium with Yankees officials asking him what he wanted for the ball. They recorded him saying that he wasn’t going to give the ball back, or at least that he hadn’t decided, and he was walking out of the stadium with the ball.

At least that’s how I remember reading it, which somehow led me to Viand, an upscale diner on the Upper West Side, with Hample the next weekend.

“The first quote you should give from me,” he told me over an eggy brunch, “is that I hit major-league quality fungoes.”

Noting my blank expression, he explained to me that a fungo is a baseball tossed into the air and hit with a bat. I might call it the dropkick of the baseball world. It used to be common for professional baseball players to acknowledge fans during batting practice by hitting fungoes to them, though they now give out so many that they simply throw them. As perhaps the most skilled—and definitely now the most famous—ballhawk in history, Hample is probably more familiar with this method of batting than he is with the gametime pitcher-batter relationship. Of the over 8,000 major-league baseballs he’s now caught in his lifetime, many have been not gametime home runs and foul balls, but balls from players who recognized him in the stands.

But he wanted me to know that he’s not always been on the receiving end of them. Once, he told me, while interning for a minor league team in Boise, Idaho in college, he summoned the grounds crew while shagging balls, grabbed a bat, and instructed them to watch him as he hit a fungo into the centerfield stands. “They all thought I was just some skinny smartass kid, and were all ready to get a good laugh at my expense.” I wanted to ask him if he went into the stands to hawk his own ball.

“That was an accomplishment,” Hample said. “That A-Rod ball was nothing. In terms of skill, it was right at the bottom—as close to 100% luck as any ball I’ve ever snagged. I didn’t even catch it, I picked it up after it hit the stands. The only thing I did right was choosing that seat for my season ticket.”

Perhaps the most elucidating thing Hample told me in our first conversation was this: “You should know that anyone who hangs out in the stands at baseball games with any regularity is not to be trusted.” To which he later added, “Except me.”

~

I’d never heard of Zack Hample before he caught the A-Rod ball. My own interest in baseball springs mostly from a dislike of New York sports media and a renewed optimism for the Kansas City Royals, the home team of my childhood in Kansas. Now living in Brooklyn, I’ve been fairly disinterested in A-Rod’s quest for the asterisked 3000th-hit milestone. On June 19, the night he got the hit, I was glancing through the scores online and saw a short article titled “Known baseball collector caught A-Rod’s 3,000th hit.” My first thought was, Is there such thing as a known baseball collector? Reading further, I saw that, besides catching over 8,000 balls in his lifetime, Hample’s written two books on the baseball—not the sport, but the object. And the best part: He said he wasn’t giving the baseball back. My imagination piqued, I began reading every story I found on Hample, then I started reading his website’s extensive FAQ and Twitter feed. By the next night, I knew I wanted to meet this guy.

As I read more, I found numerous storylines and tropes developing around the intersection of Hample, A-Rod, and this mass-manufactured bundle of rubber, cowhide, and yarn. The first, promulgated by many columnists and message board posts, characterizes Hample as an ego-driven, child-shoving, obsessive jerk who should have A-Rod’s precious ball forcefully removed from his possession. This was voiced almost immediately by Bald Vinny, leader of obnoxious Yankees fan group the Bleacher Creatures and manufacturer of unlicensed Yankees memorabilia:

That guy sucks. He pushes little kids out of the way. He is the worst ever. That guy is the worst ever. There is literally—nobody worse could’ve gotten that home run ball than that fucking guy. He’s a d-bag.

This quote in fact became one of the guiding sources for many sports columnists’ reactions the following week. Maury Brown of Forbes.com even used Bald Vinny as his sole “research” for an entire piece, ““A-Rod’s 3000th Hit, and How ‘Memorabilia Leeches’ Should Not Be Allowed at Games,” which is fairly representative of most other mainstream media reactions.

A competing narrative, voiced in roughly one out of every 20 user comments and discussion board posts, emerged almost immediately: that no one is more passionately and intellectually equipped to curate an important baseball than Hample. He has published the books The Baseball: Stunts, Scandals, and Secrets Beneath the Stitches and Watching Baseball Smarter, and extends an open invitation on his website to take anyone who would like to a baseball game with him. You could argue that the A-Rod ball isn’t even his biggest take. Some notable baseballs he’s snagged include:

- Mike Trout’s first home run

- Two of the last 10 home run balls hit in the old Yankee Stadium

- The last home run ball the Mets hit in Shea stadium

- Barry Bonds’s 724th career home run

This comment by Leon Feingold (notably, the first positive online commenter I saw was also the first to give his name) is representative, and in fact was the first I read that clued me in to his small but devoted contingent of admirers:

Actually, I’ve met Zack on several occasions, as well as seen him in action in stadiums. Not only is he GREAT to kids (gives away a good chunk of each day’s take) he’s one of the smartest, most articulate people I’ve ever met—and if he doesn’t give the ball back to A-Rod / the Yankees, more power to him. It’s much less to do with greed, and much more to the fact the guy is one of the world’s biggest BASEBALL fans.

Hate on him if you want, but you don’t know the guy. Take the time to read/hear what he’s saying and you’ll realize he’s the real deal. He’s earned my respect.

I felt my own developing narrative skewing toward the latter interpretation. At first I thought of him some sort of Rudy character—one might think he’s wasting his time obsessively catching 8,000 balls that he keeps in eight trashcans in his mother’s apartment, but is it any more crazy than attending college for the sole purpose of allowing oneself to be pummeled by bigger, stronger, faster man-children? Then I felt my narrative developing into this: This was the A-Rod of catching baseballs in the stands meeting the A-Rod of, well, hitting them into the stands. I can’t think of a single person with a greater understanding and appreciation of the metaphysical significance of the ball he caught on that day. Take out the fact that one of them is making more money than anyone should be allowed to make doing anything (which is admittedly difficult to do) and I don’t see much difference between Zack and A-Rod—most have made a life out of passionately pursuing what is, to most of us, leisure activity.

On July 3, the day he made a deal with the Yankees to give them the ball in exchange for $150,000 toward his favorite charity and a ticket to the Home Run Derby and All Star Game, Hample tweeted:

In a weird way, this whole Arod/3,000 thing is embarrassing. No one deserves this much attention for running around & chasing baseballs.

Or, perhaps, for hitting them.

~

In late July I started going over my notes and reactions after spending a month thinking about, reading the work of, and interacting with a 37-year-old man who, until the month I’d spent with him, lived a life characterized mainly by leisure and relative anonymity. His father, Stuart Hample, was a writer and cartoonist, and his mother is the second-generation heir to the Argosy Book Store, second-largest dealer of antiquarian books in New York City behind the Strand. He wields a certain degree of genteel privilege, for which he seems to exercise disdain by indulging mostly in popular, low-end diversions. Besides being a preeminent ballhawk, he also holds the world record score for the classic video game Arkanoid (he makes a brief appearance in the 2007 documentary The King of Kong: A Fistful of Quarters) and has competed in many regional Scrabble competitions. Despite having had a literary agent since he was still in college, he continually scolds me for talking about the metaphorical significance of the baseball or asking if he does all these activities to combat existential boredom, calling that “English major-y stuff.”

The thing for which most people might call Zack a loser or a slacker is probably the thing I find most interesting and admirable about him: his single-minded, lifelong focus on what most people would consider sidebar activities. When I look at my own life’s trajectory, it looks like a series of unrelated phases—the shoplifting phase, the hair metal phase, the fundamentalist Christian phase, competitive running, ballroom dancing, spoken-word performance, crabbing, et cetera et cetera ad nauseam. I haven’t been anything more than slightly above average at any of them. Zack has given himself over to two major obsessions—ballhawking and competitive classic video gaming. He is an acknowledged expert in one, and a world-record holder in the other. He tends to downplay his competitive Scrabble playing, perhaps because at his peak he was only one of the top 500 players in North America.

Even in the one thing I’ve done my whole life—writing—Zack has attained a degree of success that belies his statement on his website FAQ that he’s never been happy when in the middle of writing a book. I so wanted to trade families with him when he instructed me not to read his first book How to Snag Major League Baseballs, saying, “I’m such a different person now than I was my junior year of college.” I’m still paying off student loans from twenty years ago, and my writing only registers any of my family’s attention when they think I might be writing something bad about them.

The reasoning (or excuse; po-tay-toe, po-tah-toe) I give myself is that I simply don’t have the leisure time or attention to indulge in my obsessions to the degree that Zack does. I would even say that his few weeks of relative fame are the inevitable by-product of the time he’s been able to devote to running around baseball stadiums all over the country for the past twenty years. He told me recently, “People always say I’m at the right place at the right time, but it doesn’t make headlines when I’m at a game and I don’t catch a home run. No one notices when I don’t catch one, they only notice when I do. When I go two straight months without catching a home run it’s a major drought, but most people can’t believe I’ve caught two in one season. No one knows how close I came to Ken Griffey’s 600th career home run [which he came within five feet of before losing it in a scrum], because I didn’t catch it.”

But he did catch the A-Rod ball, or I wouldn’t be writing this, or thinking about Zack Hample and this baseball—and, more generally, The Baseball—through much of the month of July. Not to get all English major-y, but my guiding question seems to be, How did we get here? Why is a 3,000-hit baseball more consequential than a 1,658,110-point game of Arkanoid, or a Top-500 ranking at competitive Scrabble? Why are any of these things important?

I’m uninterested in Alex Rodriguez or his accomplishments. I’m not interested in the 3,000th hit itself, and A-Rod is an abstraction to me. On a team known for unlikeable, aging players with monstrous contracts, A-Rod is the oldest, least likeable player with the largest contract, part of which he’s suing the Yankees for after they docked his pay while he was suspended for using performance-enhancing drugs. I am interested in why people are interested in A-Rod, and how this ball has come to represent many of the complicated feelings baseball fans—hell, people in general—hold about him.

Perhaps the most telling quote I have is from the day after his 3000th hit, when A-Rod expressed dismay with his luck at having Hample catch the ball: “The thing I was thinking about was where’s Jeet’s guy. I wasn’t so lucky.”

An easy retort to A-Rod resides somewhere in the extensive FAQ on Hample’s website, where he quotes Legendary Brooklyn Dodgers GM Branch Rickey: “Luck is the residue of design.” It makes perfect sense that Yankees fans, most of whom despised A-Rod at the beginning of this season before he began winning games for their team again, would be more inclined to give a 3000-hit ball back to one of their most beloved players, no questions asked, as one such fan did last year when Jeter had his 3000th hit. It seems equally fitting that the fan who caught A-Rod’s ball would be more inclined to tweet, as Hample speculated the night before he retrieved the 3,000 ball:

I’ll give him the finger and a dummy ball. That man deserves favors from no one, least of all a fan.

During and after the game Hample refused to negotiate. Having written an entire book titled simply The Baseball about the dodgy relationship between players, teams, and fans in relation to balls that enter the stands, he knew what he was up against. He also knew how much the ball meant, to him and to others.

From the time I’ve gotten to know him, Zack seems to think of this ball as a best friend, or perhaps a brief, intense affair. He did confide to me while he had the ball that his girlfriend, who “cannot deal with hearing me say the name A-Rod again,” was taking a break and had left town to be with her family. During the time he had the ball, he took it on a tour of the city, tweeting ball-selfies of it with various locales and views in the background. He even took it on a date with porn star Lisa Ann, whom he has known since she used his book Watching Baseball Smarter as research for her Sirius radio show Lisa Ann Does Fantasy (er, sports). When I asked him recently if he feels a sense of loss at giving up the baseball, he mused briefly then replied, “You can still have a relationship and have it be a memory.”

Reading his book The Baseball, I was fascinated at how many passages indicated a readiness and desire for this kind of ball. Its first section alone is filled with examples from the last century of conflicts between fans, players, and team owners over who retains possession of a ball hit into the stands, and its second section includes a chapter called “The Evolution of the Ball,” perhaps the most inspired and literary work Hample has produced, giving a fascinating timeline of both the development and configuration of the ball itself and the regulations around how it is used. Finally, in the third and final section, “How to Snag Major League Baseballs,” he enthuses:

Snagging any type of baseball is exciting, but catching a home run is monumental. In addition to the intense adrenaline rush that you’ll experience, there’s the guarantee of being seen on TV, the chance of walking away with an incredibly valuable collector’s item, and the satisfaction that comes with owning a piece of baseball history.

But he also gives advice that he was prepared to put to use himself:

If you catch a significant baseball, the first thing you should know is that MLB does not have an official policy for getting it back from you. That task is left to the individual teams, and some handle it better than others…If you feel that your home run ball is worth more—emotionally or financially—than what’s being offered in exchange, you have every right to ask for something else or to simply say no.

Reading it I’ve been struck by something that now seems so obvious: baseball is the only major American sport that affords its fans the opportunity to integrate themselves into the game to the extent that a ticket purchase implies ownership of the central object of the game—the ball itself—if the fan is skillful and/or lucky enough to get it into his or her possession. And in owning the object, the fan is proxy to the mythology it contains.

~

I tend to think that the greatest mysteries in life are the ones where empirical explanations don’t solve the mystery, they just increase it. Our notions of beauty, the structure of the cosmos, the life cycle of the magicicada, the act of yawning—the baseball belongs to this list. Open it up, take it apart, and you still can’t fully explain how it moves the way it does. This is the way I feel, at least, after reading Hample’s accounts of taking one of his over 8,000 baseballs apart string by string and layer by layer, visiting the Rawlings factory where baseballs are cut from raw cowhide and sewn together by hand, and discovering that all baseballs, before being used by any major league team, have been daubed with mud from the same Delaware River tributary in New Jersey since 1938.

All this makes the roasting Hample took on social media and message boards by zealous fans, many of whom seemed genuinely put out that Hample went parading about town with this baseball that most of them insist is not his, seem paltry and silly. It also lends credence to the narrative that it was inevitable that the Yankees coerced Hample, despite his own written advice, to give them the ball. Forbes recently revealed that—surprise!—the Yankees are the second-most valuable sports franchise in the world, behind only the Real Madrid soccer team. I heartily believe that part of the “Yankee Mystique” (one of my least favorite NYC sports expressions) is achieved by controlling and consolidating the symbology. Little Zack Hample could enjoy his two weeks with the ball. They would get it back, and put it in a row with every other ball or bat or trophy or whatever else that feeds the mystique.

One only has to stroll through the Yankees Museum at Yankee Stadium to feel the power of the Yankee Mystique. On Memorial Day I took my six-year-old daughter to see the Royals play them, but unfortunately the Royals were already losing 8-0 before we got to our seats in the first inning. My advice that “every time you hear the crowd cheer, something bad just happened” was giving my daughter an existential crisis, so by the third inning I decided to take her for a walk around the stadium. The fans in the stands around us had said we should visit the Yankees Museum so she could get right before the next season, and I won’t lie, a small, dirty part of me felt a secret desire to see 27 trophies spanning a century all in a row. No doubt, my daughter was taken. She went back and forth among the trophies, then to the balls, all in a row with different people’s names and numbers on them. There were so many of them, and it seemed like the balls had self-organized, almost like destiny. Perhaps sensing my seething uselessness, she rhapsodized with a random dude next to us about how beautiful they were, and he recited to her a few of their stories. I fear I may have lost a part of her that day.

It wasn’t just because I dislike the Yankees that I actively rooted for Zack in his two weeks with the ball. There’s a certain hacker ethos at work in his method of ingesting the sport of baseball. When people talk about nerds taking over the sport, they’re usually talking about one specific social stratum: the stat geek. But this neglects a large contingent of nerds who love the sport not for its athletic endeavor, not for its endless capacity for quantifiable statistics, not as an excuse for gambling, but for its intersection with and elucidation of modern American history. Hample is actually both major types of baseball nerd: He has an encyclopedic knowledge of baseball’s intersection with history (though I’ve noticed he tends to keep it light, not making any connections that divert from standard American notions of itself), and he’s also a stat nerd, but with an important caveat: he works with an entirely different set of stats. When prescribing his methods of recording his ball collection at the end of his book The Baseball, he makes a point to state:

Here’s what it all comes down to: there’s not an official scorekeeper for ballhawks. There’s no rules committee—no national association or governing body—so ultimately you’ll have to make these decisions yourself.

But go to MyGameBalls.com, the “official” site for ballhawks to keep track of and compare their collections, and you’ll find that Hample’s stats dwarf the rest of the field. The second-place ballhawk’s collection is just more than half the size of Hample’s. If these were baseball stats, Hample would probably be batting around .650. He has cracked the system, and found a way of looking at baseball that exists entirely on the sidelines of the game itself (so to speak—I know, there are no sidelines in baseball). Many people don’t know how to take him when he repeatedly says he’s a fan of the game, even some individual players, but no team. He has transcended fandom to become a working, though tangential, part of the professional baseball ecosystem.

In the end, the Yankees beat him by convincing him that he’d won. Besides a ticket to the All-Star Game and a huge amount of swag he says he’s not at full liberty to disclose, they donated $150,000—about half the appraised worth of an item that will most certainly appreciate with age—to his favorite charity, Pitch In for Baseball, to alleviate the public sentiment that Zack is only working them over for himself.

I’m trying to make a tragedy of this, I really am. But truthfully, everyone got what they wanted. Zack gets to feel good for getting $150,000 worth of baseball equipment to third-world youth, the Yankees and/or A-Rod get the ball, and fans will probably eventually get to ogle it next to all those other baseballs in a row for years in the bowels of Yankee Stadium, where people can debate into perpetuity whether the A-Rod 3,000 ball means as much as the Jeter ball sitting next to it. We will have our story, the questions that seem so difficult and timely to us right now about Alex Rodriguez will fade the historical timeline, and Hample will be at most a footnote. Which is probably how he would want it.

~

Zack has emphatically repeated to me that there’s more to him than the baseball thing, which I tend to believe—I tend to believe there’s more to anybody than any one thing, which admittedly is probably because I’m not that exceptional at any one thing myself. One of the first things he told me was how a writer for The New Yorker, Reeves Wiedeman, had written a piece about him a couple of years ago. “I felt like I had some real conversation with the guy, then I read the piece and he just plucked out five or so lines I said, all of which made me look bad.” Reading the piece after talking to him, I can understand the choices Wiedeman made—it was a short profile on a fringe subject, so he naturally played up the kookier aspects of Hample’s personality. “But I’m more than just the guy who collects baseballs. And I’m not just a bookstore clerk, which is what he called me.”

The thing is, he kind of is just a bookstore clerk—at least if you define a person by his or her job. When on the job at Argosy, he catalogs autographed merchandise, prices books, trains employees, occasionally works the register, typical stuff that any nerd who has worked in a bookstore—myself included—tends to relish. He doesn’t seem to have put in a day there since he caught the A-Rod ball, which makes me think he wanted to finish that last sentence, “…But I don’t have to work there.”

From that first interview, I liked Zack. His demeanor—the excitable tenor of his voice, his tendency to spread himself out wherever he happened to be—indicated a personality entirely comfortable with itself. I hope I’m not sounding hyperbolic when I say he’s one of the friendliest, most open people I’ve met. One of the first things he did when we met over brunch was to invite me to a game with him. I suggested we go to a minor league game, but he told me he doesn’t do that small-time stuff. “No challenge in it,” he said.

He suggested we catch the Met-Cubs game the following Tuesday, but was a bit worried I’d be disappointed in our haul. “I love Joe Maddon as a manager, but he’s a little weird about batting practice.” He explained how Maddon thinks it just tires players out. This perhaps makes sense but limits the balls Hample and others can snag during batting practice, which I quickly learned is his favorite time of the game. Getting a player’s attention long enough for him to throw the ball to him is perhaps the time he feels most connected to the players, as he says in The Baseball:

That’s the beauty of asking for baseballs. It’s not just the balls themselves that are special; it’s the chance to interact with the players and actually feel special.

I feigned excitement as we planned for the trip Tuesday. Despite my love of watching baseball games and reading about the sport and soaking in the lore, I am actually not a fan of the baseball itself. I never played the sport, and was probably hit in the chest or the head (or even the arm) by a baseball sometime in my youth, because as an adult I’m deeply, illogically afraid of being hit by one. I tighten up a little inside every time I’m at a game and a player hits a foul to my side of the stadium. I try to contain my annoyance if I’m at the park with my kids and someone starts playing catch within a hundred feet of us. The only baseball glove I own is the one worn by my great-uncle Preacher Roe when he played for the Dodgers in the early Fifties, and it’s of no use to me since he’s a righty and I’m a lefty.

I was secretly relieved on the 7 train to Citi Field when I got a text from my wife that our daughter had swallowed a quarter. Later that night, after my daughter had the quarter removed at the hospital, Zack texted to ask how she was doing and to let me know he’d snagged 10 balls at the game. After that, I decided I might get to know him on more even footing if we met at his apartment.

On the way to his place on the Upper West Side the next week, I had to constrain myself from stopping at a multi-block book sale. I’m always fascinated by these booksellers, probably because they remind me of myself. I spent a good portion of the Aughts as an online antiquarian bookseller, buying people’s collections, appraising the most valuable of them to sell online, and giving the rest to people like the ones here who sell them for a couple of bucks to people passing by. I thought of Zack’s grandfather Louis Cohen doing the same thing almost a century ago, buying small collections from libraries and estates, selling them on the street corner until he had enough stock to justify laying down $1,000 to open up a shop on 8th Street, building up row upon row of books, each waiting to reveal itself to the person who pulled it out, until he had so many rows he had to move to a bigger space on 59th, where the Argosy still resides on six floors today.

Walking into Zack’s apartment I also thought of the fights Cohen had with John Sumner, successor to Anthony Comstock on the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, over random paperbacks with suggestive covers the vice squad found on the Argosy’s shelves. Perhaps aiming to take his grandfather’s fight a step further, Zack has covered every inch of wall space in his giant living room with a checkerboard collage of magazine pages: porn (straight and gay), pop star pinups, sports figures, cover pages (all on the top row), advertisements, ad infinitum, all arranged with an aesthetic sense he tried explaining to me.

“I want people to walk in my apartment and know this is my place. If someone sees sex or bad words or something else they don’t like on my wall and walks out, I don’t want them in my place anyway. And I try to reward close looking. The theme is People and Places. See the guy with the low-hanging cock there? Every picture around that one is looking at it.”

Despite the obvious care taken toward aesthetics, I couldn’t help thinking his walls looked like a gigantic high school boy’s locker.

“I started doing this my freshman year of college, but rearranged everything after Superstorm Sandy, when everything was closed for days. I don’t know if you knew this, but before Facebook existed Guilford College, where I went, had a print version they called The Face Book that they gave incoming freshman to let them know a little bit about the students there through a photo of them. That gave me the idea for this. It’s like an visual mixtape I give to anyone who visits.” He pointed to a stand near his kitchen, where a Guilford Face Book hung next to a photo of his grandfather Louis.

The rest of the apartment only supplemented the general impression of his apartment as temple to his myriad obsessions. The only wall that wasn’t visually mixtaped held shelves lined with VHS tapes. The Arkanoid game on which he attained his record score stood against one wall, a 78×78″ rug with a Scrabble board stitched into it lay in the middle of the giant living room, and a rubber band ball that he started when he was four years old and now weighs more than he does loomed below a room-length picture window overlooking the streets and rooftops of his beloved Manhattan from seven floors up. He pointed to two bats in the corner. “I just got those.”

This was shortly after he’d made his deal with the Yankees for his beloved A-Rod ball, which included two bats signed by A-Rod and a press conference with him. I couldn’t help thinking of something he said the night he caught the ball:

I don’t plan to give it back for a chance to meet him and autographed bats because I don’t collect bats. I collect baseballs.

He picked up one of the bats, and playfully began swinging it. “I love having a big enough apartment to swing a bat.”

He’d just returned from the All-Star Game, another component of his deal with the Yankees. I asked him how it went. “It was disappointing,” he said, still swinging the A-Rod bat and looking out his window. “If I’d known how it would turn out I probably wouldn’t have gone.”

He didn’t catch a Home Run Derby or a commemorative ball, and the weather was so bad they almost cancelled the derby, considering making it a doubleheader with the All Star Game. “I didn’t catch one ball during batting practice,” as a guy behind him kept swatting away any balls headed his direction. “Not that it matters, because they didn’t even use All Star balls during BP. That’s the first time I’ve seen that. I put up decent numbers”—eleven balls total—“but I don’t count futures balls in my stats.”

He’s now been to four All Star Games and is batting .500, having gotten commemorative balls from two of them. But, “I was there to get an All Star Game ball, and I came up short.”

He set the bat down, and opened his laptop to show me his schedule for the day. He was getting a call from MTV casting at 2, as they might be doing a show on world record holders; at 3 he was talking to a guy from Vice who was doing a short documentary on him; and he had to talk to Yankees President Randy Levine about an article he was writing for Yankees Magazine on Levine’s recommendation.

Looking over at his Arkanoid game, I asked him about The King of Kong: A Fistful of Quarters, the documentary about competitive video gamers in which he makes a short appearance. The plotline focuses mainly on two guys: the long-time Donkey Kong champion and record holder Billy Mitchell who has long, Nick Cave-like black hair and is the aging rock star of classic gaming, and Steve Wiebe, a middle-aged, obviously on-the-spectrum high school teacher who at midlife bought a Donkey Kong game instead of a sports car and applied his academic discipline to diagram the trajectories of barrels thrown down the construction site at Mario, effectively creating a Unified Theory of Donkey Kong. Wiebe, the underdog who seems to face a good ol’ boy establishment of Eighties nerds bent on subverting his obvious superiority to their hero Mitchell, is the protagonist of the show, while Mitchell is portrayed as a faded flower who uses every cheap trick at his disposal to cheat Wiebe out of beating his long-held record.

“I really think Mitchell was misrepresented there,” Zack told me. “I feel like the filmmakers had a story they wanted to tell, and they shoehorned him into that role. I’ve known him a long time, and he’s one of the nicest guys in the business.” In portraying a contingent of not-too-normal people, it’s easy to play their eccentricities for effect. I feel myself in the role of the documentarian here, struggling with how much to focus on Zack’s peculiarity without losing sight of the human qualities that make him emblematic of, well, something I can’t quite discern.

Considering Zack’s fondness for the Eighties, it’s perhaps easy to see his instinctive defense of the video game nerd of King of Kong as a defense of the idea that that kind of guy—odd, intelligent, somewhat asocial—can now be the popular guy. “It’s so funny. I wanted to be famous when I was little—I just liked the idea of being loved and the center of attention. I still feel like that, but my god, it’s…I feel lucky that I’m not more famous, because it’s exhausting.”

I asked him what life was like pre-A-Rod. “It was pretty much the same, just on a much smaller scale. There were still big to small media requests, just not as often. It used to be 2-10 people recognized me on any given night at the stadium, now it’s over 100.”

He pointed again to his laptop. He’d told me when he invited me over, “You’ve probably never seen someone do music the way I do music.” Opening up a file called “sucky songs,” he told me how he began recording songs randomly as a teenager, not knowing anything about them, just that he liked them. One day midway through high school, he decided to take the tapes to HMV, where he met an employee there who told him who recorded all the songs. This started a lifelong habit of asking anyone he knew what music they listened to, finding that music and listening to it, and adding it to his collection if he liked it or adding the song title, artist, and brief reason he didn’t like it on a list of songs he doesn’t like. He now has a 141-page file in 9-point Helvetica font of songs he doesn’t like. He finds lists on discussion boards, listservs, and Wikipedia of songs by type, systematically listens to each song, and adds it either to his iTunes or the Sucky Songs list. He has no such list of songs he does like. “Why bother? If I like it, I like it.”

He told me that this is his escape from the baseball thing. “All that stuff with the snagging stats, those guys get really competitive. Music is not a competitive thing for me.” He has a music quiz he gives everyone he knows, from his parents to his girlfriend to people in his writing group and random friends, keeping track of everyone’s scores on a file that is now five pages long with 326 participants. He also has an Arkanoid high scores list, itemized with his world record game in red, has his weight logged from 2005 the present—he started at 188, and is now 155—and has compiled all of his emails into a chronological record.

He’s in many ways a person I could have easily become if I had more leisure time. I have my own extensive records of music on Excel files that I mysteriously stopped updating around the time my first daughter was born, and roughly a third of the vocabulary between my best friend and me consists of lines from Fargo. That might be what I fear and admire most about Zack—he’s a man I could have become, if I’d only worked harder at the less important things in life. I still can’t decide if Zack never works or is always working. His method of conducting his life forces you to continually question what the word “work” means.

I asked where the bathroom was. “After the kitchen, on the left. The door’s kind of hard to see.”

He was right—the door was camo’ed into his visual mixtape. I eventually found the handle, and entered yet another dimension of Zack Hample’s strange mind.

The bathroom walls were also checkered, but with smaller, rectangular tiles—upon closer inspection, I found that he’d paneled his bathroom with thousands of calling cards he must have been accumulating for years. Book and comic dealers, restaurants and resorts, car services and mechanics, sex shops, acupuncturists, photographers, baseball card traders, musicians, hotels, bars, video shops, banks, and much, much more that I missed lined every square inch of wallspace in his bathroom. As I stood urinating at the toilet, the thought occurred to me that, despite his anti-English-majorism and desire not to be affiliated too directly with his job at his family’s antiquarian bookstore, almost all of Zack’s obsessions revolve around a central mission: preserving dying media objects. The magazine shots and business cards, the classic video games, the wall of VHS tapes, the obsessive music lists, the trashcans full of used baseballs—all of these are his quixotic attempt to cheat death.

He was waiting for me when I came out with a large paper-filled volume. “Ok,” he said. “I’m ready to show you the best part. I can’t really show it to you, because I haven’t actually seen it myself. But it’s the most important thing I’ll ever do.”

The volume read “50th birthday.” “I started doing this maybe ten years ago. I started with the girl I was dating at the time, and just asked her to write something she’d want me to read on my fiftieth birthday. Then I started just giving it to everyone I knew, telling them all I wasn’t going to read it until I turn fifty. My mom wrote in it, friends, other ballhawks, video gamers, I even ran into my girlfriend from college one time and asked her if it’d be too weird for her to write in it too and she did. My dad wrote in it before he died—it’s been hard not to read that one, but I’m determined.

“If someone told me I had choose between ever catching the A-Rod ball and getting to keep my 50th Birthday Book, it’s not even a question. I seriously can’t wait until I turn 50.”

~

I thought I understood Zack enough to write this piece before I saw him in action snagging balls at a game: a fringe character with a big heart, obsessive-compulsive tendencies, and an excess of time and money. But after roadtripping with him to a game in Philadelphia in early August—Phillies-Dodgers, if that matters here—I now feel like I was about to write a whole piece on Van Morrison without ever listening to Moondance, or maybe even without ever listening to a popular song. Despite his best efforts to get me to see him outside his ballhawking, I can now say I didn’t truly see him as comfortable, as fully in his element, as when I witnessed him do his thing during batting practice.

He had invited me to drive down with him and a couple of friends as guests of Pitch in for Baseball, the charity he and the A-Rod ball had perhaps single-handedly promoted from a minor-league not-for-profit to a player for the pittances major league players and franchises give from a small part of their exorbitant profits and salaries. When I talked to Meredith, one of their three fulltime employees, that night, she told me Pitch in for Baseball is now in negotiations with the Major League Baseball Players Association to get on the short menu of organizations given to players when they express interest in charity work but don’t know where to start.

Zack was annoyed that she wasn’t waiting for him when we arrived at the stadium gate 45 minutes before the gates opened and three and a half hours before the game started. We would have been there earlier, but we got stuck in traffic on the New Jersey Turnpike, then Zack insisted on stopping at Rita’s Frozen Custard on the way as part of the Phillies experience. (We had to settle for soft serve ice cream, as it turns out we were in the middle of a nationwide egg shortage.) He kept himself busy at the gate with the only people who beat us there, a fifteen-year-old aspiring ballhawk I’ll call Montgomery and his mom. Montgomery was the first of many people that night who were in awe of Zack Hample. Since he was the first, his wide eyes and respectful-but-continuous questioning kind of took me aback.

He’d been warning me all week that he averages the equivalent of five or so miles running up and down and across the stairs during batting practice. Having been thoroughly astounded that I’d never been to a pre-game BP, he told me to just try to keep up as much as I could. I lost him the minute the gates opened. He was already a bit huffy that Montgomery and his mom had taken his spot as first in the stadium, and seemed to relish sprinting past the portly pair.

I hung back with Jeff and Andrew, his two friends who rode down with us. Both are writer-types who make their money building websites, and neither was there to ballhawk. We got beers and sat down in the left field stands behind where Zack was already zigzagging back and forth with his glove on while the Phillies took BP. He’d already gotten his first ball of the night—and his 500th of the season, he told me—by yelling to Luis Garcia in the outfield in Spanish, “Dame la bola, por favor.”

The stands felt pretty empty, but when the first ball hit them a swarm of probably 30-40 men descended like crabs upon it. It was quite a rush watching the men and children converge until someone held up the ball in triumph, then disperse back to their respective positions and wait for the next baseball to sail in their direction. The next one sailed over my head, into the stands directly behind where Jeff and Andrew were sitting. Jeff reached back and grabbed the ball, and excitedly held it up. I have to admit, in that moment I was intensely jealous and wished I’d hung back with him so I could be the one holding up the ball. A kid in a Dodgers cap was hovering close by, and Jeff offered him the ball. The kid looked Jeff up and down and seemed to mutter, “Pshaw,” then shook his head and walked away.

I immediately went up to see the ball Jeff was waving at me. “Can you believe it?” he said, rotating the ball in his hand. “It’s my first ever. It’s lighter than I expected. And look at the scuff here, where it hit the stands.” He handed it over to me for inspection. I don’t know exactly why, but holding the ball in my own hand filled me with a profound disappointment. It seemed too white, too small, too new to signify anything. It just looked like a baseball.

I walked down to where Zack was positioned in a half-crouch, his arm outstretched and glove at the ready. “Hey, can you back up a row?” he asked, shooing me back with his glove. “I set myself up in the stands with at least two empty rows between me and everyone else, for maximum lateral movement.” Once I was a safe distance, he began telling me about getting assaulted the previous week at Yankee Stadium, the first time this had happened in his twenty-plus years of ballhawking. “I don’t think it had anything to do with the A-Rod ball. The guy was twenty or so years old, and was there with his dad. It was weird. He just grabbed me from behind, put me in a headlock, and swung me around. I thought he was punching me in the face, but now I think my head was just hitting his ribcage or something. I’m pretty sure from my experience with him that he was mentally not all there, and I remember his dad from a couple years ago, when I snagged a ball in front of him, saying something like, ‘You better watch yourself.’ Neither of them were apologetic when I called security on them.” His attention shifted to home plate. “Hey, watch this Maikel Franco in the batter’s box here. He’s got the most majestic swing. I’d love to catch a game ball from him.”

As if on cue, a crack of Franco’s bat sent a baseball scorching right at us. I ran out of the way as the ball dropped three stands in front of us. A young boy scooped it up, and Zack looked at me as if to say, “That would’ve been mine if I wasn’t babysitting your ball-fearing butt.”

So went most of BP: Zack keeping his distance from people until someone recognized him, chatting long enough to satisfy anyone’s curiosity that he was in fact “the A-Rod guy,” all the time his eyes darting back and forth with each bat crack. At one point a ball came rolling near the outfield stands where we were, out of anyone’s reach in the stands or anyone’s attention on the field. “Time for the glove trick,” Zack said, rushing for his backpack.

I knew the glove trick from reading his book The Baseball—he had rigged a baseball glove with a string attached where someone’s hand would go, two rubberbands stretched between the ends of the thumb and finger webbing, and a Sharpie pen wedged in the webbing to prop it open. He pulled the contraption out of his backpack, ran over to the edge of the stands near the ball, and dropped the glove onto the outfield while holding the end of the rope. Swinging the glove until it landed beyond the baseball, he used three gentle nudges to get the ball almost directly below him, and lowered the glove onto the ball. The glove clamped loosely around the ball like one of those claw machines at the arcade, and he pulled the ball up to a round of muted ooh’s from the people around him in the stands.

I filmed the whole thing and sent it to my wife, whose immediate response was to ask, “Does that really count toward his season tally?” Whereas I thought of it as a brilliant, ingenious parlor trick, she thought it was theft, or trespassing at least. “At what point does he have to admit he’s doing something kind of wrong here?” she later asked me. I didn’t—still don’t—have a ready response to this question, and I think this is at least partially why Zack has so many detractors: He has cross-purposed baseball stadiums into playing fields for his own game, a game replete with its own rules, stats, and modicum of skill and cunning in which he is the greatest player in history, in the midst of a large crowd of people who are there to see another game entirely. And the game he’s playing more than occasionally disrupts the spectacle of the game which pretty much everyone else is there to watch. I felt a twinge of this when I saw another guy during BP with a vintage Royals shirt, and when I said, “Go Royals” to him he just looked at me for a second and said, “I’m just wearing this to get [former Royals pitcher Zack] Greinke to throw me a ball.”

But before I could properly address this guy, the last “home run” of batting practice sailed into the stands. A tallish guy, probably in his 60s, was reaching to catch the ball in his cap when Zack leaped in front of him, snatching the ball right as it was about to land in the guy’s hat. The guy with the empty hat in his hand looked at Zack, ball in glove. The guy in the Royals shirt looked at me and I looked at him, both of us thinking the same thing: Fight? But then Mr. Empty Hat smiled widely in recognition, put one arm over Zack’s shoulder, and walked back up the stands with him. By the time they got to me, the guy was jokingly asking if Zack had the A-Rod ball on him and non-jokingly offering him free use of his season tickets.

Zack brushed him off gently, and asked me if I wanted to hit up the visitor’s bullpen with him. I had no idea what this entailed, but followed him up and around to where a decent crowd of people were leaning over the railing watching Dodgers starter Alex Wood warming up. “Aw, man,” Zack said, “Montgomery beat me here, and even switched to his Dodgers gear.” The fifteen-year-old he’d talked to at the gate was leaning in and coaxing the pitcher, catcher, and pitching coach to throw him a ball. “I taught him this trick, too well I guess.”

I should say here that the beginning of the game marks the end of prime ballhawking time. From this time forward there are fewer balls to catch, and exponentially more people in the stands to maneuver around. For the first time since we arrived, Zack sat down in his seat. He used this time to catalog his haul—six balls for this game—recording stadium, area, player he got it from, method, and probably a couple of things I’m forgetting, and tweeting any out-of-the-ordinary acquisitions. Jeff had brought him a cheesesteak sandwich from Tony Luke’s, and he was tweeting about the fact that the cheese wasn’t melted when the woman sitting next to him, bleached-blonde with a tattoo covering her upper arm, asked if he was really about to tweet a picture of his sandwich.

“I have over ten thousand Twitter followers,” Zack said, not looking at her. “That’s way more than Tony Luke’s.”

“Is the sandwich really that bad?” she asked, then squinted her eyes. “Wait a second. You didn’t even eat one bite, and you’re complaining about it to your ten thousand followers?”

“I’m not complaining about the taste. I’m complaining about the cheese.”

“Alright,” she said. “Let me take a look at what you’re about to tweet. In the meantime, at least take a bite of it.” The two of them then composed the tweet together:

Disappointed that the provolone isn’t melted on this @tonylukes pork sandwich. That said, it still tastes good.

Within five minutes, Tony Luke’s tweeted:

Sorry about the cheese.

As Zack came as close to a genuine social interaction as I’d seen since we arrived, I talked to Meredith and some of the board members at Pitch in for Baseball, who had come out to say hi to Zack and Jimmy Rollins, another donor to the charity, and catch a game (their office is in a suburb of Philly). One of them showed me a photo of 4,000 bats outside their warehouse, recent gifts of Wilson Sporting Goods, and beamed about the increased reach and exposure they’ve experienced this summer, due in large part to the donation Zack had squeezed from the Yankees.

Sometime around the sixth inning, team mascot the Phillies Phanatic put what looked like a bazooka on its shoulder, and used it to launch foil-wrapped hot dogs into the stands. Zack jumped up, glove in hand, and waited. When I saw the silver projectile flying in our general direction, I knew he’d catch it. Another jumping catch, and he had his first hot dog to add to his stats.

He of course immediately tweeted a photo with it, and waited in his seat for replies. Many were encouraging, even admiring, but a few weren’t, like this random middle-aged Mets fan from Long Island:

I’m sure you’ve guzzled lots of hot dogs homo

Zack had been showing me mean tweets as he got them throughout the night, always doing the same thing after showing me: waving at his phone and saying “bye-bye” before making the tweet invisible to him. As far as I know he never deletes tweets, his or otherwise—he wants to provide as accurate a record as possible of his exploits—but he seems to have developed, perhaps as an emotional survival mechanism, this ritual of plugging his virtual ears to the noise and general negativity regularly hurled in his direction from people whose game he’s taken and used for his own game.

Oh yeah, the game. I’m generally indifferent to both the Phillies and the Dodgers, but the long-suffering Royals fan in me felt some sense of empathy for the fans gathered at Citizens Bank Park (at least the two-thirds of them who weren’t rooting for Dodgers) who just saw every star player traded at the deadline last week and know their team is headed for a probable 100-loss season. This is the type of team I’ve been rooting for from the late 80s until last September. This part of me felt that wonderful short-term optimism in the bottom of the seventh inning, with the score tied 1-1, when the Phillies loaded the bases and Maikel Franco—he of the majestic swing—stepped up to the plate, and for this night at least every Phillies fan was tapping into his or her hidden reservoir of optimism, ready to break out in wild communal catharsis if he could only use that majestic swing to deposit a ball into one of their hands between the foul poles.

And he did just that. The whole stadium knew from the crack of the bat that the ball would not land in the field of play. The crowd rose to its feet and roared, Zack jumped up into the stairs by his seat, I ducked, and the ball representing four runs made like that silver-clad hot dog right at our section, then landed a few rows down.

I heard it hit, then saw people scrambling for it, but honestly, I could have cared less about the ball at that moment now that I knew it no longer meant me harm. The home team was up four, their next young star had his first career grand slam, and we all knew they would win the game. Who cares that the Dodgers would take the next two games and the series and move on toward their probable place in the playoffs, and the Phillies would almost certainly finish the worst team in the NL East, if not the entire National League? For this night, the Phillies and their fans were winners, I was in a food coma from multiple sausages and cheesesteaks, and I remembered why people sit through inning upon inning, out upon out, misfortune upon misfortune as a bunch of overpaid and overgrown boys throw, hit, and catch a mass-produced ball of yarn with cow skin tied around it by low-paid workers in Costa Rica.

As these thoughts hazily assembled themselves in my addled mind, I looked down the steps in our aisle, and saw perhaps the most dejected person in the stadium. There, glove on his hip and shaking his head, was Zack. He looked up at us despondently as the crowd cheered deafeningly for their new hero rounding the bases. Never was the contrast between him and everyone else at the stadium more clear. I stopped cheering long enough to take in the solitary figure surrounded on all sides by the maddened crowd. He’d missed Maikel Franco’s first career grand slam ball by three rows.