1. Nemonymous

A FEW YEARS ago I heard about a literary magazine called Nemonymous in which all the stories were published anonymously, with the identities of the writers only revealed in the next issue. At the time the appeal of this to writers was absolutely baffling to me – why would anyone not want to be credited for their work, even if only for a few months? I was equally flummoxed as a reader – I was more likely to buy a fiction magazine if I knew it contained stories by writers I liked, so hiding this information seemed deliberately perverse. I dismissed the magazine as a literary curio, a gimmick, and promptly forgot about it. Recently however I’ve been thinking about it again, prompted by

reading Italo Calvino’s letters in which I noticed a recurring theme, his saying things like this:

A text must be something that can be read and evaluated without reference to the existence or otherwise of a person whose name and surname appear on the cover.

And:

The public figure of the writer, the writer-character, the “personality cult” of the author, are all becoming for me more and more intolerable in others, and consequently in myself.Or:

Basically, I am convinced that not only are there no “major” or “minor” writers, but writers themselves do not exist – or at least they do not count for much.Then:

It is with my works that you have to establish a dialog, not with the author in his real-life person.

On February 7th 1973 he even dedicates a whole page of a letter to Pier Pablo Pasolini to explaining his choice to remain silent, “I quickly realized I had no place in actuality.” He’s talking about his decision not to engage in public debate on the issues that his friend thought might concern him: “It is no accident that I have gone to live in a big city where I know nobody and no one knows I exist.

Of course, five lines in a book of over 600 pages will only really stand out if they connect in some way with the reader. In this case, Calvino’s reflections on the importance (or not) of the writer in relation to the text chimed with thoughts I was having myself. When I was younger, I decided that I wanted to be a writer. As you do when you’re a teenager and don’t know the first thing about anything, I imagined books with my name emblazoned across the front, facing out from bookstores’ shelves. I even imagined a range of similar covers, like Calvino’s of the time, or the striking black-and-white, almost art-deco designs that had graced Iain Banks’ novels in the UK (and which, in my opinion, have never been improved in subsequent reprints). Those similar designs make a statement which, by virtue of belonging to the author rather than a specific work, tells readers something about the writer – that they’re edgy, or comforting, classy or schlocky. They draw the attention away from the texts themselves and towards the personality of the author.

This emphasis on the artist over the individual work of art suits the commercial side of the arts industry; once the artist has an established identity, they’re more likely to develop an established fandom to go with them – whether they’re a writer, a band or any other kind of artist. As a consumer this suits me too; I am a completist. When it comes to my personal favorites, I try to read/listen to as much of their work as possible, every short story or obscure novella, every B-side. The cult of the artist is ingrained in me.

It is odd then that my favorite artists shape shift, changing voice and style and tone: bands who never produce two albums that sound the same and writers who occupy a new literary space with each book. Calvino was just such a shape-shifter. He would seem to be an odd writer for a reader obsessed with a writer’s identity to fall under the spell of, but perhaps this was an early sign of attitudes to come.

Calvino occupies a strange place in European literature. Never a bestseller, yet his books remain constantly in print in English. He was one of the most inventive, playful and intellectual writers in the 20th century, lauded by the likes of Salman Rushdie, Carlos Fuentes, Gore Vidal (who made a concerted effort to promote him in America), Susan Sontag and John Updike, and his book sleeves frequently carry The Guardian’s description of him as “The greatest Italian writer of the 20th century,” yet his stature remains lower than the likes of Borges or Marquez. Calvino never won the Nobel Prize for Literature. “He can wait,” was his delightfully grumpy response to being told of Marquez’s win by Rushdie, and unlike Borges, his name isn’t used to evoke a particular style of writing. This latter (and perhaps the former) is partly due to the fact that Calvino seldom occupied the same literary space for long enough to stamp his footprints all over it. From the political pastorals of his early short stories in Adam, One Afternoon, to the playful parodies of Italian life in Marcovaldo, through to the experimentalism of the mid-60s onwards, Calvino was constantly on the move, the lightest traveller who stayed in each of his worlds just long enough to send back his report to ours before moving on.

Calvino was fortunate to live before our modern interconnected world came into being. He liked to take his time over letters, not fire off emails. He enjoyed being able to retreat, to step away, something harder to do now when your every move can be followed via Google (a quick web search could find how long it has been since you published a book or gave an interview, read at an event or gave an opinion on an important matter of the day). What mattered to him was the text.

This was not always the case. His early works were heavily influenced by growing up in San Remo and fighting against the fascists as part of the Partisan Army. He was a card-carrying member of the Communist Party and wrote for its journals. He was very much the “committed writer.” So what changed? Well, he resigned from the Communist Party in 1957, no longer able to tolerate its attitudes to the horrors of Stalinism (prompting the soul-searching essay “Was I A Stalinist Too?”), and as he wrote in the letter to Pasolini, “My reservations and allergies towards the new politics are stronger than the urge to oppose the old politics, and I no longer had a position to uphold since I had ruled them out one by one.” In other words, he, like all people, had changed. But for the public figure, such a change has to happen on two levels – on the level of Italo Calvino the man, and “Italo Calvino” the writer. When the former changes, the latter has to be changed if it is to remain true, but this is not necessarily so easy to do when you have readers who all have an idea of who “Italo Calvino” is, and who may be resistant to any alteration of that idea. In an Introduction to a re-issue of his first novel, The Path To The Spiders’ Nests, Calvino would comment that it is better to never have to write your first novel, as it creates a persona for you while you are not yet fully formed.

2. Me.

Thinking about it now, Nemonymous sounds like a fantastic idea – a way of divorcing the writer from the written to allow a reading based purely on the text. Only the words remain. I went online and found that it had stopped publishing in 2010, so my change of heart must have taken place over the last five years or so. What changed?

Well…me, obviously. The more you learn about the reality of publishing, and the longer you go without making any kind of breakthrough, the sillier your youthful fantasies become. By the time of my first proper publication (a Sherlock Holmes story in a collection published by Titan Books) I was simply hopeful that I would be read as one of twelve contributors and grateful when reviewers thought it stood up well in comparison with the other stories in the volume. In fact, while I was lucky enough to receive some very nice comments on the story, I was even grateful for the couple that were less complimentary, as having any kind of engaged feedback from a complete stranger who had taken the time to read my work felt like a victory.

So, having had the vain-gloriousness (thankfully) kicked out of me, what is left is a curious sense of freedom – I can now put my self to one side and get on with the work. While I might not have many publications, I do have a lot of ideas. And these ideas don’t really fit into an easy genre – or rather, don’t fit into the same genre. Like Calvino, my mind flits around too much to stay in one groove, which is unlikely to be attractive to publishers wanting their author-brands and reassuringly similar book jackets. Every so often I indulge in the fantasy of publishing a series of pieces simply as “Anonymous” with no indication as to the identity of the author (gender, ethnicity, class, sexuality) – taking the writer completely out of the equation. But even this would be a false modesty, as the fantasy involves it being known that these pieces were written by the same person, creating a recognizable body of work even if the author remains in all other ways unrecognizable. This is another form of vanity – and quite possibly pointless. A writer’s identity is not just their name on the front, it’s in their prose style, in their phrasing, in their choice of ideas to explore. If you want to get away from yourself, you have to do more than change your name, you have to change the way you write, the assumptions you make, the trails you follow and how you make those choices in the first place.

3. Calvino Again

It’s certainly something Calvino was aware of. He went further than most to disappear into his work, especially from the middle of the 1960s when he actively looked for ways to break away from the expectations of his audience and from the prison of his own perspective – first by writing stories that were increasingly distant from his own life and experiences (his characters varied from an immortal shape-shifting being called Qwfwq to Marco Polo) and then by introducing the eternal, objective elements of the sciences and mathematics to his story structures, as if hoping to use geometry to force his work into a shape that contained some kind of objective truth, immune from the contaminating influence of the subjective.

Except…even the choice to do this is subjective, and reflective of your point of view. Calvino’s attempts to get away from his “I” paradoxically formed the basis of an essay (the most “I” of all texts) in which he outlined his idea of a “literature machine” to produce stories, based on certain literary rules:

What will vanish is the figure of the author, that personage to whom we persist in attributing functions that do not belong to him, the author as an exhibitor of his own soul in the permanent Exhibition of Souls… The author: that anachronistic personage, the bearer of messages, the director of consciences, the giver of lectures to cultural bodies.

And, he might have added, the writer of essays. In a touch typical of Calvino, the very desire to escape from himself and into his work pushed him back into the realm of the “I” again. There was no way out that way.

Calvino in 1950

~

4. ”I want to walk in the snow and not leave a footprint.”

When I was thinking through the ideas I would want to discuss about Calvino and Nemonymous, the above quote came into my mind. It may sound like another line from Calvino’s letters, but comes from the pen of Manic Street Preachers’ lyricist and (sort-of) rhythm guitarist Richard (or “Richey”) Edwards. His words initially just seemed an incredibly concise way of summing up Calvino’s thinking. But, as I considered some of Edwards’ other lyrics, I realized that it was more than that, and that he and Calvino were addressing similar preoccupations (ironic, given that Calvino is one of the few writers the Manics haven’t quoted on a record sleeve), albeit in different ways. But to explain this connection, I first have to explain the Manic Street Preachers.

In America they mean almost nothing to the general population despite the fact that the shiny FM-rock of their first two albums, 1992’s Generation Terrorists and 1993’s Gold Against The Soul musically begged America to love them. True, they included somewhat derogatory comments about America at times, but this was a bit like an indie-kid at a school disco who’s desperate to dance with the prom queen but is too cool to pay her the open attention required to make her notice. Elizabeth Marcus’ 2015 documentary of the band, No Manifesto, includes footage of the band attending an award ceremony, having been nominated for British music magazine Q’s “Best Act In The World Today” category in 1998. Each nominated artist had a clip of a recent single played, captioned with the UK and US sales of their most recent albums. First; Radiohead, with UK sales of 1,450,400 of OK Computer and 2,346,400 US sales. Then Oasis, with 1,833,600 UK sales and 1,018,050 sales of Be Here Now. The Verve were up next, with 3,193,000 UK and 1,378,400 US units of their Urban Hymns album shifted. Then, it’s the Manics, with UK sales of their album This Is My Truth Tell Me Yours standing at 1,038,000 copies, and US sales of…25,475. Yes, that’s right – sales of five digits across America. Despite that, they still won the award.

To be fair, they’ve had rotten luck. Whenever they toured the US, something would go wrong and disrupt the tour. Laryngitis, for example, or the L.A. Riots (yes, really). And a 2001 album launch in Havana probably didn’t help make the US their oyster either. Or, the poor relationship between themselves and the US arm of their record company, whose reaction to a new Manics album was to send it to be remixed and chopped to pieces. But when they band handed their label The Holy Bible, in 1994 something odd happened. They liked it. Yes, they had it remixed, but when they sent their version back to the band, something even odder happened – the band liked the new mix. A tour was set up. The label thought they could hang the album on the college rock hook. Singer James Dean Bradfield and lyricist Richard Edwards were due to fly out to America on the 1st of February, 1995 to begin publicity duties, before the rest of the band joined them for the tour. Maybe, just maybe, they might make it across the pond.

Like Calvino in the world of literature, Edwards occupied a slightly unusual place in the band. A friend of the other band members since childhood, he was originally their driver, but he looked so cool that they decided to make him part of the group, even though he couldn’t play a note on the guitar – a skill he singly failed to pick up during his entire time in the band. The first two albums saw him and bass player Nicky Wire share lyric-writing duties and do most of the talking in interviews. They said they wanted to sell 16 million copies of their first album and then split up, set light to themselves on Top Of The Pops and “mix politics and sex, and look great on-stage.” Meanwhile their “mess of eye-liner and spray paint” aesthetic (mixed with leopard print, tight white jeans and feather boas) saw them dubbed “The Glamour Twins.” Edwards was more usually known as “Richey James” at this point (the press also sometimes referred to him as “Richey Manic”), using his middle name instead of his surname for his public persona. In this, he was like his fellow “glamour twin” Nicky Wire (real name Nicholas Jones) whose loud-mouthed controversy-stirring contrasts with his love of doing the domestic chores at home. However neither James Dean Bradfield nor Sean Moore have felt the need to disguise their real names, suggesting that Edwards must have had a reason.

Two years later they’re a different band. Musically abrasive (comparisons with Nirvana’s In Utero are common), the band hit the stage in military uniforms culled from services across the globe. By The Holy Bible’s release Edwards had taken over the majority of the lyric-writing duties, helped shift the band’s look to a harder, military style, and became the focus of the media and fan-attention aimed at the band, with stories that he was suffering from anorexia, alcoholism, nervous breakdowns and committing acts of public self-harm, all of which were reflected in the lyrics. Edwards stated that he had chosen the album’s title because whether you are a believer or not, a holy book is supposed to represent the truth, and that’s what he wanted his lyrics to represent. But the songs on The Holy Bible defy simple autobiographical readings.

Take the album’s centerpiece “4st 7lb,” (which translates as 63 lbs) a song about anorexia, a condition Edwards appeared to suffer from (although it is unclear if this was ever formally diagnosed). Yet, it’s not autobiographical; the song is from the perspective of a female sufferer. Edwards’ problems were well known at the time of the album’s release (and he had never been shy in talking about them), so why take on a persona rather than simply making the song starkly from his own point of view? There can be no doubt that much of The Holy Bible was extremely personal. Take “Faster,” which opens with a series of definitions of the writer and the way he is perceived:

I am an architect, they call me a butcher.

I am a pioneer, they call me primitive.

I am purity, they call me perverted…

I am idiot drug hive, the virgin, the tattered and the torn.

The opening line reflects his self-harming, the most infamous example of which was in 1992 when British journalist Steve Lamacq questioned whether the band were “for real.” While replying, Edwards produced a razor blade from somewhere and calmly carved “4REAL” into his forearm (those with strong stomachs will easily find online a picture of this wound taken later that evening should they feel the need). The song title reflects his eating disorder (a “faster” being someone who fasts) but as the song progresses he starts to incorporate more of the outside world into his “I,” as though attempting to absorb everything into a single point – himself. “I am stronger than MENSA, Miller and Mailer / I spat out Plath and Pinter,” he continues, “I am all the things that you regret / A truth that washes, that learned how to spell.” The song “Die In The Summertime” repeats the same trick: opening with another image of personal self-harm, and then Edwards edges towards omnipotence – “I have crawled so far sideways / I recognize dim traces of creation.”

Incendiary live performance of “Faster” from Glastonbury 94

He hasn’t finished there. The Holy Bible contains not one but two songs about the Holocaust, both of which he finds a way to insert a first-person perspective into. There’s more. Comparing the whole of mankind (a gendered term I use very deliberately) with a list of despots and serial killers on “Archives Of Pain” (“Sterilze rapists / All I preach is extinction”) shouldn’t shock any of us because as “Of Walking Abortion” points out, humanity has “Hitler reprised in the worm of your soul.” If the rest of the album has been accruing the evidence of our collective guilt, it is this song that issues the final judgment; “everyone is guilty,” before concluding with a devastating howl; “Who’s responsible? You fucking are.” Just as Edwards (and everyone listening) has taken on the identities and crimes of humanity as a whole, the more he says “I,” the less of a person he actually becomes.

Other songs written around this time suggest an attempt to put a distance between the “I” of Richard Edwards (the man) and that of “Richey James.” As well as the use of a female narrator on “4st 7lb,” on the track “Yes” the “I” is a prostitute. Nicky Wire speculated the song also reflects how Edwards saw himself. In song after song Edwards submerges his identity, either beneath a narrator or a library of references. Of course, Edwards is hardly the first person in the music world to play with the concept of identity. From David Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust to Eminem’s Marshall Mathers, music has often been a realm in which the ordinary and prosaic can be transformed into the glamourous and extraordinary. Escape from ordinary life being one of the principle appeals to young people everywhere that inspires them to pick up a guitar or take to the mic. But while Edwards’ initial transformation was entirely typical (small town boy to glamour-puss rock star), the changes in identity in his lyrics began to serve the opposite purpose. Rather than helping him escape his reality, he became someone else in order to better reflect and confront it.

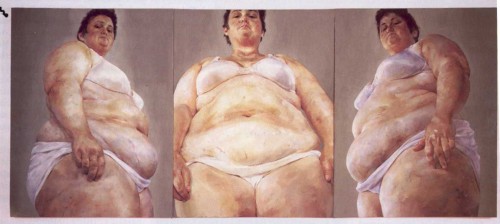

Despite a positive critical reaction, The Holy Bible sold poorly. In a moment of supreme irony, it was released on the same day as Oasis’ debut Definitely Maybe, an album that would define the British guitar-music scene of the 1990s and (along with Blur’s Parklife) create the concept of “Britpop,” a musically conservative movement of mostly middle-class bands presenting a pantomime of what they thought was working class culture – bad hair-cuts, baggy clothing, heavy drinking, and lowest-common-denominator lyrics. The Holy Bible, with its inventive guitar-playing, post-punk drumming, gothic bass and crammed so full with words and ideas that it speaks in tongues, thrashed out by a genuinely working class band who looked like a paramilitary unit, was commercially all at sea. Even its cover art, artist Jenny Saville’s “Strategy (South Face / Front Face / North Face)” which depicts a triptych of an obese woman in her underwear staring out of the canvas looks like nothing else released at the time.

Jenny Saville, “Strategy (South Face / Front Face / North Face)”, 1993/1994

Oil on canvas (triptych)

274 x 640 cm

All the while Edwards’ mental health deteriorated, culminating in a spell in The Priory clinic. Then, on the first of February 1995, the day he and Bradfield were supposed to fly out to prepare for the American tour, Edwards went missing, and has not been seen since. But he was heard from. When he vanished, the band was working on its next album (eventually released as Everything Must Go) which contained five songs featuring his lyrics, and he had handed each member of the band a folder full of lyrics which would later form the basis of their 2009 album Journal For Plague Lovers.

Two of the songs written by Edwards on Everything Must Go take disassociation a step further. “Kevin Carter,” about the Pulitzer Prize-winning photographer of the same name, suggests a kinship between himself and his role as a lyricist to present what he saw as the truth, however unpleasant, with that of the war photographer who was criticized for taking pictures during conflicts while doing nothing to help the subjects (Carter later committed suicide), while “Removables” is about…well…I’ve no idea, to be honest. But both involve Edwards moving beyond conventional syntax as he grasps after the truth of his subject: “Vulture stalked white piped lie forever,” “The elephant is so ugly he sleeps his head / Machetes his bed Kevin Carter kaffir lover forever / Click click click click click,” “Killed God blood soiled skin dead again.”

There’s also a song about an animal going slowly mad in captivity, while “Virginia State Epileptic Colony” on Journal For Plague Lovers may have been named after an institution that secretly chemically sterilized patients deemed “mental defectives with carcogenic potentialities,” but it’s hard to believe that its account of the daily lives of patients in such an institution (“cleaning, cooking and flower arranging”) was not based heavily on his own personal experience. Paradoxically, these lyrics that specifically focus on the lives of others (and other species) can be seen as among the most autobiographical that he ever wrote, his “I,” his writer’s personality, hidden behind assumed personas. As Picasso said (and as quoted on a Manics’ single sleeve), “Art is the lie that helps us understand the truth.” Edwards’ work is a perfect example of the truth of Picasso’s statement.

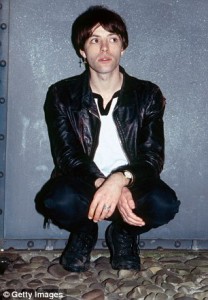

Richard Edwards.

5. Calvino also tried to work this trick.

In the mid ‘60s he also abandoned the human viewpoint completely in his Cosmicomic stories, which are mostly told from the point of view of Qwfwq, a being that has existed from before the Big Bang in a number of forms (from cellular organism to dinosaur, dust cloud to amphibian). But these stories continue to reflect Calvino’s personality as the stories are all examples of anthropomorphism, and Qwfwq’s quirks and thought processes are all recognizably human, and allow Calvino to follow his interest in marrying science and fantastical imagery and logic. In the same way Richard Edwards wrote semi-autobiographical pieces from the point of view of characters experiencing similar problems to him, Calvino abandoned the human entirely in persona, but was unable to escape infecting the non-human with his own viewpoint. Even when he attempted to follow the logic of the Tarot , or structure stories based on the principles of mathematics he was still drawn to humanizing these concepts, using them to tell the stories of people with recognizable motivations, aims and desires. In other words, to tell stories, to be a storyteller.

Calvino tried to escape his “I” by creating characters and styles of narration at increasing distance from the reality of the human called Italo Calvino. Edwards tried to escape it by absorbing the world and becoming a conduit for it all – all the ideas, culture, art, genocide, corruption, filtered through him until he becomes a signifier for everything. But if Edwards was attempting to escape his “I” by making it represent the whole world, he of course failed, instead making the whole world into him. From such a situation, escape is all-but impossible. When you have taken on the world and just found yourself wherever you look, existence becomes a room walled with mirrors with you standing in the middle, reflected outwards to infinity in all directions.

Clearly, both Calvino and Edwards felt driven to communicate, even whilst feeling the urge to retreat into silence. What causes this tension that drives people to commit words to paper, recite poems to audiences, sing out their emotions publicly whilst regretting the exposure that comes along with it?

Animation based on Calvino’s Cosmicomic story “The Distance From The Moon.”

6. Silence & The Self

“The pursuit of silence seems to be a peculiarly human activity. Other animals run away from noise, but it is noise made by others that they try to avoid. Only humans want to silence the clamor in their minds. Tiring of the inner chatter, they turn to silence in order to deafen the sound of their thoughts,” political philosopher John Gray wrote in his book The Silence Of Animals. With professorships at Oxford University, Harvard, Yale and the London School of Economics, Gray has published several books including Straw Dogs: Thoughts On Humans and Other Animals, taking as a general theme the idea that the Enlightenment concept of humanity developing towards increasing perfection is a myth. He sees it as a comforting lie that bares little relation with the truth.

In The Silence of Animals, Gray looks at how humans are the only species that needs to actively seek quiet, for other animals it is simply a birthright. Equally it is hard to imagine any other species other than the human suffering from an existential crisis – a cat does not ask itself if they are being suitably feline, a dog may seek approval, but I doubt it questions this, or any other, desire (although anyone who’s ever seen a nervous animal that knows it has done something its owner will not approve of may dispute this). Only humanity, with its desperate need to communicate with its words, questions its identity and feels the need to establish a concrete “self,” and be recognized for it by others. Which is, of course, where writing comes in – or, as Gray puts it, “Only humans use words to construct a self-image and a story of their lives.”

Writing often does not happen on the page. William Burroughs (who, like Gray, has been quoted on Manics’ record sleeves) described the act of writing as “like a film. Exactly. A writer is sitting there and he’s looking at a film and he’s trying to get it on paper, that’s what’s happening.” The Sherlock Holmes story I wrote, “A Betrayal Of Doubt” began as a scene that played itself out for me in my mind with no effort – it was as though I were watching a filmed adaptation of a story not yet written. By writing the scene, I removed it from my consciousness – I quietened the Gray’s “inner chatter.” This chimes with his observation that “Whereas silence is for other animals a natural state of rest, for humans silence is an escape from inner commotion.”

So, we are driven to paradox – in order to have peace, a writer must write. The only way to achieve silence is to communicate.

7. Back to Calvino

As early as 1972, Calvino was able to write to a friend that he was writing “very little and that worries me less and less.” But, of course, he did continue writing, publishing fiction less frequently but with several of his better-known works still ahead of him. The final novel to be published before his death in 1985, Mr. Palomar, consists of a series of vignettes in which the titular character attempts to examine a series of natural phenomena in its most minute detail – like the Palomar telescope being aimed down to Earth rather than out into space. Mr. Palomar is not presented as a man with a great inner life – rather he fulfills the role assigned to humanity by Carl Sagan as the universe’s method of examining itself. “He is not contemplating, because for contemplation you need the right temperament.” Mr. Palomar does not feel the need to communicate what he sees, it is enough for him that he sees it, or at least tries to. Anything more is superfluous as, “Mr. Palomar tends to reduce his relations with the outside world.” It’s not hard to see Mr. Palomar as a reflection of Calvino – particularly given his ambivalence about writing. Still, at the time of his death two years later, he was in the middle of writing a series of lectures on literary values which would be published posthumously as Six Memos For The Next Millennium, while Mr. Palomar becomes a trap sprung by the act of writing it.

8. Private and Public.

Calvino had in fact anticipated these tensions back in the 1950s when he wrote the three novella “romances” (in the historical sense of the word) that form Our Ancestors. In “The Baron In The Trees,” the titular Baron leaves the ground and never returns to it, spending his entire life in the branches of the forest, observing everything that goes on beneath, while “The Non-Existent Knight” is an empty suit of armor that wanders the world, kept alive by force of will “’(a)nd faith in our holy cause!’” It is tempting to see these two as reflections of the personas the writer is forced to take on, the private and the public, the observer who requires distance to see clearly, and the actor in the world who has to create a shell of armor around themselves to survive. Fittingly, the other novella in the volume “The Cloven Viscount” tells the story of a man sliced in two by the impact of a cannonball. This tension between retreat and engagement, silence and communication was not solved until death solved it for him as the age of just sixty-one.

9. Unnecessary armor?

It is tempting to apply this same imagery to Edwards, who was initially brought into the band simply because he looked good on stage. Officially he was always credited as the band’s rhythm guitarist though he is said to have played on only one studio recording and, while his guitar was plugged in on-stage, it was always turned way down in the mix. He was in effect playing air guitar but with an actual guitar, like a non-existent knight moving its unnecessary armor (although psychologically it may have been extremely necessary). Edwards was declared dead in 2008 but no conclusive evidence of what happened to him has ever been found. Whatever the truth of the matter, he chose silence…but even he could not resist one final act of communication, presenting a folder of lyrics to each of his band mates just before he stepped away.

10. Just a job.

There is also another possible reason for feeling compelled to write despite reservations. William Burroughs (who was quoted on the sleeve of the Manic Street Preachers’ 1991 single “Motown Junk”) was the oddest of beasts – a writer who distrusted words to the point of considering them the result of a virus that diverted human evolution. He saw the syllabic language form as a weak spot that could be exploited by the powerful and thought that words could be used as weapons in psychic warfare – even claiming to have forced an espresso bar to close by making recordings of the conversations had there and playing them back on different days: “Making recordings and taking pictures of some location you wish to discommode or destroy, then playing recordings and taking more pictures- will result in accidents, fires, removals, especially the last.” Indeed, a volume of his letters carries the title Rub Out The Words after a phrase he used – an indication of how much he distrusted them. When asked about working in a medium he distrusted he replied:

I’m a writer, it’s my job, that’s all. What’s to rationalize? I’m working with words. I think they’re a very inadequate means of communication and maybe will be replaced in time, but right now it’s what I’m working with. So?

12. Postscript.

It’s winter and I am standing in a hot, stuffy venue called the Manchester Albert Halls, which is crammed full people wearing feather boas and leopard print, military gear, or simply t-shirts and jeans. There’s a strange atmosphere – excitement but also tension. The wall behind the stage at the far end of the room is hidden by camouflage netting, just as it would have been twenty years before, had this venue been used the first time around. I’m here to see the Manics.

The lights go down and the screams go up as three men walk into the stage. A tall, thin man in pale khaki picks up the bass guitar. In the shadows at the back, a smaller man walks purposefully to the drum kit. Finally a man in a blue sailor suit picks up a guitar and walks up to the mic. As at every show since 1995, there is an empty space on the singer’s right, where the fourth member used to stand. Richey’s spot.

They’re about to play the whole of The Holy Bible, to celebrate its twentieth anniversary. The reason for the excitement is obvious, but the tension is born of concern – the album is a huge effort to play and sing, if only from a technical point of view. So many difficult guitar parts, and so many words for the singer to remember whilst playing those parts. Bradfield had even expressed doubts as to whether he would be able to pull it off. And also, these are three men in their mid-40s who are financially comfortable, with settled family lives, about to attempt to recreate the anger and nihilism of their mid-20s. They have always played songs from The Holy Bible in their live sets, but only one or two, and the more difficult have been left unplayed for years. Can they still play the songs with the intensity required to make them work? Can they still do justice to their missing friend’s masterpiece?

The album’s opening sample (from a documentary about prostitution) comes through the speakers – “You can buy her, you can buy this one’s here, this one’s here and this one’s here. Everything’s for sale.” And they’re off, the surprisingly jaunty riff of “Yes” kicking the crowd into life, with an intensity that barely lets up for the next fifty minutes. It quickly becomes apparent that Bradfield has decided to solve the problem of having so many words to sing by allowing the crowd to sing a lot of them. We oblige without needing the invitation, singing lines like “We all are of walking abortion / Shalom, shalom / There are no horizons” and “No birds, no birds / The sky is swollen black / A-a-a-no birds, no birds / Holy mass of dead insect” like they contain all the truth in the world. From the savage guitar solo at the end of “Archives Of Pain” to “4st 7lb”’s gentle coda (“Self-worth scatters / Self-esteem’s a bore / I long since moved to a higher plateau”) somehow, they pull it off. There’s a second set of hits and rarities to come but they could have stopped the show then and the whole audience would have been too overpowered by what they had just seen and heard and sung and screamed and danced to to have cared.

For me, this was a chance to not only listen to the most intelligent, the most truthful, and the just damn coolest (by virtue of not giving a toss about being cool) rock record ever recorded played live, but to exist within it, as the music – amplified but with nowhere to go – disorientates my mind and commands bodily responses I’m barely aware of obeying, while I sing every word of every lyric (memorized years before) back like they’re the only words that exist.

After they finished in the UK they finally took The Holy Bible to America for a short, catastrophe-free tour, before coming back to the UK to play a few more shows culminating in a homecoming gig at Cardiff Castle which was broadcast on the BBC –extended highlights here:

https://youtu.be/Cdoh7Jo3EWY

Even though nothing has been known about the whereabouts of Richard James Edwards since February 1995, his work remains triumphant, even without its author. The Holy Bible continues to sell steadily to younger generations unaware of the backstory of its main creative force, just as Calvino’s books continue to be read by people who know him purely as a name on a book-cover. In this, both accidentally found the same solution to the problem – their words outlive them, it is the work that remains.