IT’S RARE THAT architecture is at the center of a social revolution. Or even a literal one, though it’s hard to say if what’s happening in Taksim Square is a revolution. At least yet. But in this Q&A, Istanbul-based architecture critic (and Taksim protester) Gökhan Karakuş logs in on the protests, politics and the architectural sins of Prime Minister Recep Tayyıp Erdoğan and his conservative AKP party.

~

JK: When did you first go to the Taksim Square? What did you see?

GK: The events started not in Taksim Square but in the neighboring Gezi Park on May 28. As construction was continuing on a project to create a pedestrian area around the park, activist groups were upset by trees being cut down and removed. Four sycamores were destroyed and uprooted by a backhoe, and the first to notice were members of Taksim Solidarity. They’re a group of urban activists who since 2011 have been fighting the government’s attempt to raze the park and resurrect the 19th Century Ottoman-era Artillery Barracks which had been there.

Members of the group include everyone from artists and professionals to trade unionists and academics and students from the Istanbul Technical University School of Architecture next door, where I also teach. The whole thing happened in the middle of the day when people were at work, but since the school is close, faculty and students were there first, then quickly were joined by local neighborhood activists from Beyoğlu (the district the park is in). In fact, the “lady in red” getting pepper sprayed in the iconic photograph is Ceylan Sungur, a research assistant in the urban planning department at Istanbul Technical University.

Protesters primarily tried to block the construction, which is when the police showed up. The Parliament Member Sirri Surreya Onder ran under the backhoe and announced to the construction workers and police that the construction was illegal and that they could themselves be held responsible for their actions. This stopped the construction. Onder did the same thing the next day. An MP from Istanbul, he’s also a well-known filmmaker who’s been involved in Turkish politics since the seventies and was jailed as a political prisoner after the 1980 coup. He’s known for his leftist yet independent politics.

Both days, the peaceful protesters were met by tear gas and pepper spray, and as the events were reported on Twitter, more and more people started coming to the park. After Onder blocked the backhoe, people started a sit-in in the park. At first it was a group of a few hundred. By May 30, this had grown to a few thousand. That night, the scene was festive and peaceful. It was mostly made up of young professionals, students and residents of downtown Istanbul, but come the morning, the park was raided by police who threw out the protesters. This was the breaking point. Both the excessive violence and images of it were all over Twitter. Later that day these small protests spread across Gezi Park and to the neighboring square and surrounding districts. Twitter and other social media was pivotal in announcing the protests, and there was a kind of day-by-day battle with the police. They gained control again on Saturday the first.

People from across Istanbul started to converge on Gezi. The police had their tear gas and barricades, but this convergence brought together segments of Istanbul’s society that were seen as apolitical: young people, professionals like before. Also gays and lesbians, soccer supporters, and many women came too. Political activists including nationalists, communists and old-guard Turkish republicans bulwarked these groups. For me, it was a once in a lifetime situation. I found myself walking up Abdi Ipekci Caddesi, a kind of Madison Avenue shopping boulevard, towards the barricades. I was in the front of a group of thirty-some young people, with a Turkish flag in my hand and my wife and friends around me. It was like going off to war but in a surreal 21st Century way. We were applauded by people sitting in café’s sipping wine and shoppers coming out of Prada.

JK: Did you visit the square before the protests? What was it like?

GK: I teach at the nearby Istanbul Technical University, so I’m in and out of the park. It’s nice if a bit ragged, being the only green space in the city.

JK: So if it’s the only green space, can you describe the rest of the city a bit? Are trees a rare commodity?

GK: Gezi Park is part of a larger green area that stretches down towards the Bosphorus, but because of its location close to the dense urban area of downtown Beyoglu, it’s a green wedge in what is, basically, a crusty and thick urban fabric. The park is in the middle of downtown Istanbul. Although not used so frequently, its green spaces provide a meaningful break in the city with air and sunlight.

Ironically, I was in the park the week before the protests walking through it on a Saturday night, and it struck me then seeing how many people were using it, just how valuable it is to have that kind of park in such a dense city.

JK: So tell me more about the park itself.

GK: Gezi Park and the adjacent Taksim Square are the modern center of Istanbul. They’re connected by a set of stairs as part of a master plan the French architect and urban planner Henri Prost completed in 1940. They can be considered the same urban zone with the park being slightly above the square.

The park was built in the 1930s with the modernist vision of the Mayor of Istanbul, Lütfi Kırdar. A doctor, he sought to create an area for modern culture, sport and leisure in the middle of the city. He enlisted Prost, who also worked across Morocco from Marrakesh to Rabat.

History seems fitting here too. The park replaced an Orientalist neo-classic Artillery Military Barrack which was the center of the 31 March Incidents in 1909 where Islamist Conservatives rebelling against the modernist reforms of the Ottoman State were defeated. It’s no coincidence the present conservative government is eager to put that building back up, but ironically as a shopping center in a Las Vegas decorative style. Their understanding of architecture is completely scenographic and symbolic, like a stage set basically. They feel if they recreate Ottoman forms, the country will turn back to some kind of Ottoman-like conservative Islamic state.

JK: So, was this the first time you’ve protested? Been tear-gassed? Protested in Turkey? I mean, from the outside, protesting in Turkey seems a dangerous thing, but you know, the Occupy Wall Street people were often pepper-sprayed for no reason, arrested unfairly and it’s just come out that their phone numbers were all logged by the government.

GK: Street-based activism in Turkey is somewhat dangerous. Police training and methods are lacking. If you’re in the front lines, directly facing the police, it can be precarious. There’s the potential of tear gas canisters being fired at close range. I was worried about the police charging and using their bludgeons indiscriminately. Five demonstrators have died so far in similar circumstances. Most of us had never participated in political demonstrations, so it can be frightening especially when the crowd panics in front of tear gas and the police threats.

On Saturday there was a back and forth struggle with the police all day, but they backed off around 3PM, largely thanks to the Beşiktaş soccer team’s ultra fans, Çarşı. They maintained a solid front before the tear gas and police. Their steady patience at the front line kept those us of behind them in place up until the police retreated. Then, we all rushed into the park shouting ideological slogans. The feeling of walking back in was amazing, powerful…. It’s a standard thing to walk in a park. You know, “It’s like a walk in the park,” the saying goes, but the effort here transformed it. To be with those thousands of people taking control of our urban space, our park, in our city came with a sense of communal empowerment I’d never felt.

Soccer fans in Europe have often been associated with violence. But in Turkey and Tahir Square they've fought for freedom.

The demonstrations that night in and around downtown Istanbul spread to the capital city and throughout the country. The official count was, I believe, 78 of Turkey’s 81 provinces. Gezi Park became a camp as the area around it was barricaded off including access from the adjacent Taksim Square on one side.

During the occupation a kitchen, clinic, library and performance spaces sprung up. So many volunteers were donating sandwiches that some had to turned back. People were singing and chanting in large groups. Everyone from gays and lesbians to famous actors and doctors walked around the park to applause. Banners and slogans mocking Prime Minister Recep Tayyıp Erdoğan’s rhetoric were strung up everywhere, across the trees and the park’s surfaces.

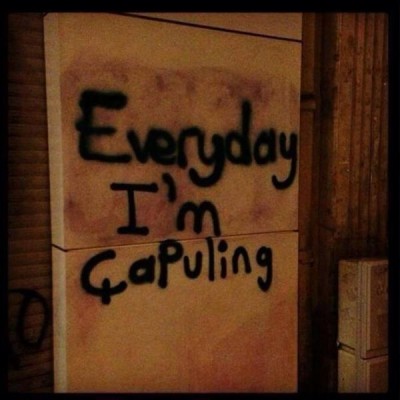

He’d called the protestors “street rabble,” which was co-opted. The word Çapulcu means something like vagrant, bum, perhaps looter. The noun was turned into a verb Çapuling, meaning I am being a vagrant, bum etc. If you were on the side of the protests then you were a Çapulcu and were Çapulling. It even sprouted a Wikipedia page.

This last week thousands of people have circulated through the park taking part in this movement to create a unique utopian public moment in the city and in the country.

JK: So, is that a first for Turkey? And like all Utopias, do you think it can hold?

GK: It’s a unique moment in the sense that democracy in Turkey was always a top-down affair. It’s taken 90 years for people to understand that if they don’t actively participate in this democracy then expecting it to work is unrealistic. It took the citizens of Istanbul declaring the park and square public space, a civic space, a democratic space, for this to happen. This spatial performance of utopia is, I believe, the first step in the momentous realization of a truly democratic nation with primarily an Islamic population.

JK: Can you explain some of the context for the use of urban spaces in Istanbul and how that relates to Erdogan’s rule? So many Western news outlets are writing about him as one of Turkey’s “most powerful” or “strongest” or “most effective leaders” since Attaturk.

GK: The situation now has, of course, turned to a much larger political response to the authoritarian rule of the AKP (Justice and Development Party; the very word “development” seems prophetic) and Erdogan himself.

He emerged from the street level of politics of a lower income neighborhood in Kasımpaşa in Beyoğlu. He comes from a conservative Islamic base and when elected in 2002 was initially thought of as democratic. But, slowly, in over a decade of rule, it’s become clear that he’s only interested in propagating a society based on Islamic values with his close supporters’ commercial interests as the key driving principal. The man wants to build a shopping mall in a park that was once a military barracks. And he wants that shopping mall to be some kind of Ottoman kitsch. The neo-Ottoman design sheen is a way to sell it to his conservative constituents as something meaningful.

Construction has been one of his main economic drivers. Contracts go to those who are closely aligned to him. Projects like the Gezi Park abound all over Istanbul and Turkey as a way financially to strengthen his political and economic associates.

Architecture and urbanism, though, are still at the center of the debate as the Prime Minister inexplicably continues to raise the ire of many by saying one day we will build a shopping center in Gezi Park, the next day a mosque, etc.

JK: So is he planning mosque and shopping center? Together? As one?

GK: There are no specifics other than saying they want to build a mosque. For the mall, he’s said first they would “restore” the defunct Artillery Barracks as a shopping center but later said it could be a museum. The mayor and others chimed in with similar vague assertions. Beyond the question of why and how the PM is at the head of these planning issues and not the mayor, there’s the whole dynamic of how public architecture is created in this country.

There’s a long-standing problem with how the spaces of modern Turkey are designed and organized. Architecture here has always been a top-down cultural policy. Turkey moves forward, and now architectural strategies reflecting a pluralistic, modern society are becoming one of the key topics, but look at what it took to make that happen. I mean, five deaths? Thousands of protesters….

JK: The other thing you hear here in the US is that this has precipitated a “crisis” for Erdogan that includes larger political issues. What are they?

GK: Democratic institutions geared towards the organization of public life need consensus and pluralistic input from all stakeholders to be effective. Most of the Islamic world lacks this kind of civic, public culture. In Turkey we’re seeing now an active urban middle class that’s demanding livable public space and a form of government and society that’s at peace with modern, cosmopolitan life. They’re demanding civic space to breathe and live, to express their feelings and ideas in public life, which is why it was so great to see gay protesters. People are demanding urbanism and to a lesser extent an architecture that reflects this desire.

Public lands, like the park, have been sold to real estate developers without any oversight or public dialogue or debate. Across the country, parks, forests and the sea coast have been sold through these backroom deals.

The Istanbul Aquarium was built on the shore of the Sea of Marmara in Florya, Istanbul, as an apparent public project, but then barely a year later a much larger shopping center was attached directly to it, exposing the project’s original commercial intent.

The Aquarium was just plopped on top of a seashore park. And it’s been visually and ecologically disastrous. Water from the fish tanks was channeled directly into the sea attracting fish from the sea, which then attracted large flocks of birds. Unfortunately, since the aquarium is directly adjacent to the airport, planes landing and taking off on the runway about 500 meters away have been flying directly into these birds. Is it any wonder people distrust his building aims?

JK:As an architecture critic, you’re hugely aware of how space and urbanism play into political aims, can you draw this out for us here? Even historicize it…

GK: Well, I can say categorically that we need more public participation in the large-scale projects being planned for the city. Modern democratic societies organize public and civic life through a consensual dialogue among stakeholders representing the public, experts (architects, planners, developers) and elected officials. Turkey is barely beginning. And we’ll see what happens from Erdogan’s meeting with protesters yesterday.

But, will this happen? Will there be a discussion? I don’t know. As an architecture culture in Turkey we, architects and architectural critics (there are only a few architectural critics in the whole country), have to be more vocal about how we can create modern architecture with roots in living, local cultures (not Ottoman, which is dead, but Antatolian rural cultures, which are still alive).

JK: Also, there’s an unmistakable relationship in recent protests with public spaces, e.g. Occupy and Egypt’s Tahir Square ….

GK: I don’t think Occupy is so much a model as an interesting parallel in how urban dwellers feel a level of responsibility to the environment in which they daily live. The current dynamics of the situation show that most of the people living in the cosmopolitan and urban parts of Istanbul are the ones out in force in the streets and in the park. The people using public space are the most angry and concerned about how the city is being altered in an autocratic and undemocratic way.

JK: What is happening there now?

GK: Right now the situation is fluid, though that might be an understatement. Tuesday the police attacked. And Erdogan promised to meet protesters. The police have raided Taksim Square but have left the people in the park alone. The whole situation is happening on Twitter and social media as the Turkish media have failed to report what is going on in the protests in a meaningful way. They’re reporting the sequence of events but with no analysis. The AKP government has shackled the press through threats and buy-outs, leaving no meaningful critical voices. Twitter and the Internet have been a catalyst here, just like in other countries and situations where the media is tightly controlled.

~

To see Gökhan Karakuş’s photo essay about Istabul and architecture, click here.