I am not free while any woman is unfree, even when her shackles are very different from my own. And I am not free as long as one person of Color remains chained. Nor is any one of you. – Audre Lorde

A FEW YEARS ago, I heard Angela Davis speak about having gone to Palestine as part of a delegation of U.S. feminists of color. She described visiting the Occupied Territories, and passing through checkpoint after checkpoint, barbwire topped fence after fence. After a while, she said, she couldn’t tell if she was inside the walls or outside them, whether she was inside the cage looking out or outside the cage looking in. She described the experience of imprisonment in a related fashion – saying that it was the experience of being incarcerated – watched, monitored and regulated by others all day long – that made concrete for her the surveillance society outside the prison-industrial complex, which watches, monitors and regulates us all. The cameras and cages may be (at times) less visible, but they are no less real.

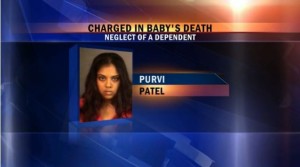

In a sense, this is what the Purvi Patel case has done for me. The recent sentencing of Patel, a 33 year-old Indiana resident, to twenty years imprisonment under a feticide law, has reminded me that we all, as women, are at risk of having our reproductive and other liberties snatched away at any given moment. Although the Indiana feticide legislation, like others of its kind, was designed to prosecute violent crimes against pregnant women by others, its implementation against Patel opens a terrifying floodgate of future similar prosecutions of women for having abortions, miscarriages, using drugs or otherwise being seen to ‘harm’ their pregnancies.

The facts are these: in August 2013, Purvi Patel sought medical attention in a Mishawaka, Indiana emergency room for excessive vaginal bleeding. She eventually revealed to the medical team that she had miscarried, and disposed of the fetus in a dumpster. The fetus was in fact later discovered there by authorities. At the crux of the legal case was the issue of whether Patel had miscarried or self-aborted, whether she had delivered a live baby or a nonliving fetus, and whether her pregnancy was even far enough along to deliver a viable live child. Ultimately, even though a toxicologist testified there was no trace of such drugs in her bloodstream or the fetus, the prosecution successfully made the case that Patel self-induced the abortion with illegal drugs obtained online from Hong Kong. In addition, their argument hinged on the notion that she had delivered a live baby which she had then killed, or at least allowed to die. The image of the baby thrown away, left to die in a dumpster, was a damning part of the prosecution’s narrative. Another key aspect of the prosecution’s case was proving that Patel’s stage of pregnancy was far enough along to be viable, 25 to 30 weeks. In order to do this, they used an antiquated examination called the “lung float test.” In the words of Emily Bazelon in The New York Times Magazine,

The idea behind the test – which dates from the 17th century – is that if the lungs float in water, the baby took at least one breath. If they sink, then the fetus died before leaving the womb… If that sounds like the old test for witchcraft – if an accused witch floated, she was judged guilty; if she sank, she was innocent – it’s also about as old and nearly as discredited.

With such untrustworthy evidence, the prosecution was able to convict Patel of not only feticide, but neglect of a dependent– two seemingly contradictory crimes.

Alongside the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, the Patel case signals a new era of reproductive injustices to come – in which women may fear seeking needed medical attention lest they be arrested, tried, and convinced to shockingly long sentences like Patel. Although the Purvi Patel case has been discussed extensively for its reproductive justice implications in the domestic and foreign press alike, what has been less prominent is a critical discussion of how Patel’s ethnic background impacts and frames this case. The fact that Patel is of Indian origin, a brown woman in the heart of the American Midwest, a South Asian face in the era of post 9-11racial profiling, is in fact critically important in this narrative of criminalized reproduction. It’s hard to ignore the fact that both Patel and the only other woman prosecuted under Indiana’s feticide law, Chinese immigrant Bei-Bei Shuai, were non-white. Women’s studies scholar Ashwini Tambe has written about the Patel and Shuai cases in the context of conservative U.S. perceptions of India and China as places with a disregard for human life, where forced sterilization and one-child policies are de-rigueur. In her words, “China and India serve as poster children in global evangelical crusades against abortion.” In addition to this context, it is critical to understand Patel’s prosecution as a woman of color in the U.S., which highlights what Angela Davis said so clearly about the prison-industrial complex,

Imprisonment has become the response of first resort to far too many of the social problems that burden people…. These problems often are veiled by being conveniently grouped together under the category “crime” and by the automatic attribution of criminal behavior to people of color.

To deliver up bodies destined for profitable punishment, the political economy of prisons relies on racialized assumptions of criminality – such as images of black welfare mothers reproducing criminal children – and on racist practices in arrest, conviction, and sentencing patterns. Colored bodies constitute the main human raw material in this vast experiment to disappear the major social problems of our time.

Yet, Purvi Patel is a different kind of embodied chattel being consumed by the American prison-industrial complex. As opposed to what Davis describes as “images of black welfare mothers,” Patel is perhaps symbolic of the brown-skinned South Asian terrorist out to destroy “American family values” and therefore the nation itself. If this seems farfetched, consider that the Tea Party and religious right have long been united in a deep-seeded Islamophobia, an anti-Muslim and anti-immigrant sentiment which easily extends to non-Muslim South Asians and Middle Easterners as well. Even President Obama is called a Muslim, or “almost” one, a category of person at odds with the future success and wellbeing of the American nation.

At the same time, these same Christian extremists have framed abortion as a sign of the coming apocalypse and have used this understanding to spur on increasing violent anti-abortion campaigns. (Lest we write off such beliefs as those of fringe extremists, let us remember that the apocalyptic Christian Left Behind series is extraordinarily popular, with multiple New York Times bestsellers and millions of books sold.) Such abortion-as-apocalypse discourse is connected as well to the notion of the fetal citizen, the ultimately vulnerable, unprotected person “unjustly imprisoned in its mother’s hostile gulag.” In the words of scholar Rosalind Pollack Petchesky, the fetus becomes a fetishized figure, both “already a baby,” representing the “patient” as separate from the mother, and a sort of “‘baby man,’ an autonomous, atomized mini-spacehero.” Protecting the fetus, then, becomes equated with protecting God and the nation; anti-abortion work becomes anti-terrorist work as well. From this perspective, the Purvi Patel case is an almost perfect storm – a woman of South Asian decent whose reproductive decisions supposedly bring the integrity of the nation itself into jeopardy; she becomes seen as a reproductive terrorist who threatens the very fabric of American society.

Those of us who see the Purvi Patel case as an act of gross injustice must remind ourselves that Evangelical and other right wing religious values are not the purview of jobless extremists. The belief system that equates anti-terrorist, anti-immigrant and anti-abortion stances, that views the protection of the fetus from the whims of women’s reproductive decision making as part of protecting the nation, the future and God, is one held by physicians, lawyers and politicians alike. Consider that Purvi Patel was first reported to the police by Kelly McGuire, one of her emergency room doctors, who is also a member of the American Association of Pro-Life Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Dr. McGuire was so invested in the case that he apparently followed police cars to the scene while still in his scrubs, and examined the fetus on site, pronouncing that it was viable. Subsequently, the police interrogator seemed to perseverate on the ethnicity of Patel’s partner, asking repeatedly, “Was he Indian?” The judge in the Patel case, Elizabeth Hurley, was the first superior court appointee by Indiana’s conservative governor, Mike Pence. Despite defense arguments that Patel’s Miranda rights were ignored, and she was questioned when recovering from sedation and blood loss, Judge Hurley permitted the jury in the case to see a video of police interrogating Patel in post-operative recovery. The judge is also quoted as saying that Patel “treated the child, literally, as a piece of trash.”

The Purvi Patel case has become a clarion call to those who believe in protecting women’s reproductive freedoms. Yet, we activists and organizers must also understand the way that this case simultaneously reveals right wing racist and xenophobic politics. There is an organized backlash to abortion rights happening in this country, married to an anti-immigrant, Islamophobic apocalyptic fervor that holds fetal citizens far more dear than female ones. Purvi Patel is not a terrorist, nor is any other woman who exercises her reproductive rights. Yet, if we do not understand her case in relation to the politics of the religious right, in which immigrants and abortion both threaten the security of the nation, we will risk many more such violations of justice. While Patel is the one facing this terrible sentence, her case signals how deeply we all are unfree.

This is quite confusing. Can you comment on her conservative Hindu upbringing and its relation to her keeping the pregnancy secret? You haven’t address why she would place the fetus in the trash can in the first place. While I appreciate the underlying idea for which you are reaching, it feels one-sided and not completely thought out. The conservative evangelical patriarchal america, is it at all like the conservative patriarchal caste system of India?

Vale muito a pena, recomendo a todos.

Excelente curso, melhor investimento que fiz!

Aprendi no modulo Corel Draw e Photoshop que levei

9 meses aprendendo em outro curso, agora vou

abrir a caixa e investir no curso da silhouette cameo.

Para aqueles que buscam aprofundamento teórico e prático utilizando um

método de produção eficaz que busca aperfeiçoar todo processo de produção, da elaboração da

Arte a Estampa Perfeita passando pela impressão da forma correta.

Ele é altamente qualificado sobre assunto, te deixa seguro para quem está começando.

Eu e meu marido estamos começando no negócio de canecas

e camisetas (aguardamos ansiosos por um curso de camisetas!) e, com certeza, vocês farão a diferença para nós.

Parabéns Alex pelo cara que você é e pelo seu curso.

SUB – Problemas com as tintas – Visita na casa de uma aluna para descobrir problema.