~

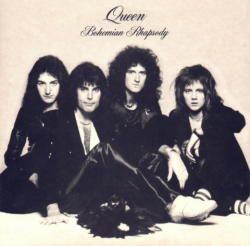

FREDDIE MERCURY died 25 years ago today. A quarter century gone, he remains the paragon of rock frontmen, his singular talent undisputed. And yet he is as enigmatic now as he was in 1991, as difficult to penetrate as the lyrics of his signature song, “Bohemian Rhapdosy.”

Freddie’s backstory is as unique as any in the long and oft-zany annals of rock ‘n’ roll. Farrokh Bulsara was born on 5 September, 1946, in Zanzibar—then a British protectorate—to Bomi and Jer Bulsara, who hailed from the Gujarat province of India. They were Parsis, Zoroastrians who had fled Iran to avoid religious persecution a thousand years earlier. So Freddie came to the U.K. by way of East Africa by way of India by way of Persia—not quite the same as growing up blue-collar in a flat in Manchester.

Unlike many of his rock contemporaries, he went to college, where he majored in art. He took a job selling secondhand clothes at Kensington Market. Although he was possessed of one of the finest pure singing voices ever bequeathed a mortal man—he could have out-Pavarotti’d Pavarotti—he had no formal vocal training. He was one of the best live performers to ever grace the stage. He named himself after a god. He was fastidiously, Pynchonesquely private, and became notorious for declining interviews. Although he had romantic relationships with women, he was, as he put it when asked, “as gay as a daffodil, my dear.” And when he died on 24 November, 1991, at the age of 42, it wasn’t because his plane went down, or he drank himself to death, or OD’d on smack, or choked on his own vomit—you know, the hackneyed rock star causes of death. Freddie died of bronchial pneumonia brought on by AIDS; he remains arguably the most famous person to die that way. This is the guy who wrote “Bohemian Rhapsody,” which is understood to be some sort of personal statement. Not the easiest psyche to try and divine.

Like the Book of Revelations, “Bohemian Rhapsody” is, by design, confusing, strange, and seemingly nonsensical. Like the Book of Revelations, and again by design, it resists line-by-line analysis. If we invest our time trying to decipher every single word—Scaramouche? Fandango? Galileo Figaro?—we get nowhere. To properly divine the true meaning of the song, we must look at the composition as a whole—lyrics and music.

Many listeners take the song’s violent images at face value, believing that the plot, such as it is, concerns a murderer confessing to his crime. In a song that’s clearly intended to be allegorical, this literal interpretation is too simplistic an explanation, and it doesn’t square with the title—perhaps our most important clue. Bohemian indicates an unorthodox, artistic lifestyle; in 1975, when the song was released, it’s shorthand for gay. “Bohemian Rhapsody” is about Freddie Mercury a) coming out to his mother, and b) reconciling his own sexuality with his conservative upbringing. The murderous imagery—the gun, the trigger, the killing—is a metaphor for active homosexual engagement (“put a gun against his head, pulled my trigger, now he’s dead”). When he sings, “Momma, I just killed a man,” he’s not disclosing that he killed a man, but that he “killed” a man.

In the first two verses of the song, he confesses to giving in to his homosexual impulses, which to him is a matter nothing short of life and death (“Life had just begun, and now I’ve gone and thrown it all away,” “I don’t want to die, sometimes wish I’d never been born at all”). He’s depressed, wistful, unsure of himself.

The mock-operatic bridge—and who but Queen could pull that off so successfully?—represents Freddie wrestling with his inner demons. These are all voices in his head. Part of him is excited (“thunderbolts and lighting!”) by the “silhouetto of a man, Scaramouche,” and part of him beseeches the Almighty (Bismillah is the Islamic equivalent of “In the name of the Father, Son, and Holy Ghost,” or, “In the name of all things holy”) to “spare him his life from this monstrosity”—i.e., his preference for other guys. It is telling that the voices who “will not let [him] go” belong to the tenor, baritone, and bass parts. The females (men singing female parts, actually) lobby for his release; it’s the men who have a hold on him.

He comes out of this tug-of-war resigned to his fate (“Beelzebub has a devil put aside for me!”), and as he repeats the end of this line, his voice climbing the seventh-chord notes (“For me! For me! For meeeeeeeeee!”)—and if this part of the song does not cause your spirits to soar, you are made of stone—he gradually accepts, and embraces, his sexuality.

During the song’s six minutes, he goes from a place of denial/fear (“I don’t want to die”), to a place of anger/indignation (“can’t do this to me, baby”), and after bargaining (“let me go!”), to a place of acceptance (“any way the wind blows,” cue: gong). It’s basically the Kübler-Ross model, set to some of the most glorious, complex, and beautiful music ever recorded by a rock band. A rock band, it must be pointed out, called Queen.