IT WAS IN the late 1980s when both my youth and a decade took one another’s hand and simultaneously slouched toward what seemed to be an untimely end. Like many of my generation, as the 90s loomed I found myself psychologically solo at the threshold of adulthood—surrounded by the shrapnel of death and divorce, bad skin and bad company, and ten years of ill-advised hairstyles. These pre-Oprah times were the surly days before talk therapy and helicopter parenting, an era where teens, floundering in the undertow of adolescence, grabbed hold of whatever they could: bottles and bongs, expeditious rec room hook-ups, and, most reliably, music.

For some, this meant noodling along with The Dead. For others, the salvation was reggae or rap or metal—turned up to eleven, of course. For kids with lesser plights, such as those of the pompom variety, pop was the only release needed. But for a good portion of us raised on Doritos and the bomb, we were shown the way from our school desks to our desk jobs by classic rock—that noisy, electric genre borne of a war that was anything but ours and anything but cold. A genre that was unafraid to acknowledge, taunt, and wrestle its demons one Jimi Hendrix guitar solo, one Keith Moon drum solo, one primal Roger Waters scream at a time. In the drowning days of my high school years, when circumstances both tragic and trivial threatened to yank me beneath the surface, it was classic rock that served as my personal flotation device.

Despite the swagger and aloofness of these particular rock gods, they were a merciful breed. Repeatedly they came to my emotional rescue by throwing album after album my way, years after their original releases, like a successive fleet of psychedelic life preservers. Maybe it’s because these bona fide womanizers knew just how to reel in an underage girl. Or maybe it’s because the music will prove to be as enduring as Bach (and I don’t mean Sebastian), but whatever the case, Let It Bleed, Led Zeppelin II, Who’s Next, Axis: Bold As Love, and Dark Side of the Moon were the compilations that saved me—not from death per se, but despair. They resonated with my core, they sounded how I felt, both in good times and bad times. And when I went to the record store, with my sweaty, wadded babysitting cash to get this music, it returned the favor by getting me. I felt understood and undergirded. Rock was indeed my rock.

A good part of this genre’s allure was that it was first introduced to us not by our peers or our parents, but by our idols—our hippie aunt, our hip uncle, our Trans Am-driving neighbor, the enigmatic lifeguard in the AC/DC tank top who never took off her shades, or most likely, the untouchable older sibling. Such was the case for me.

Twice a month, for the greater part of my youth, my stepbrother came and stayed Friday and Saturday nights with us in his allotted custody slot. For my younger sister and me, these bimonthly visits were like hosting royalty—a lanky, nonverbal king whose hair always needed cutting and whose gym bag invariably revealed the bare necessities: neon track shoes, ironed Sunday Mass khakis, and a triumvirate of hard-case cassette holders.

This trio of small brown suitcases—attachés for the 80s teen—held my brother’s entire music collection, which consisted mostly of The Rolling Stones, Pink Floyd, everything The Who had ever released, and those three, three-lettered bands that shouted to me from their plastic tape spines: VAN Halen, DEF Leppard, LED Zeppelin. Soon after arriving, my brother would line up these pleather cases on the guest room carpet, popping them open one by one, and slowly raise their lids as if they held ransom cash and not a Houses of the Holy kept intact by masking tape or a copy of Head Games so worn it required rewinding by Bic pen.

Other than his driver’s permit, these were my brother’s prized possessions. His chosen musicians weren’t my mother’s Anne Murray or my father’s Eddie Rabbitt or even my very first album ever: The J. Geils Band’s Freeze Frame. No, this stuff, I sensed, was art. It was categorized and caressed; it was magic over Muzak. These weren’t the bands I’d been hearing in the waiting rooms of my childhood; Simon and Garfunkel might be for allergy shots and Elton John orthodontics, but Janis Joplin belonged to something else entirely. Something I was also impatiently biding, but couldn’t yet name.

When my brother finally deemed me cautious enough to handle his tapes, I opened them the same way a curator might peer into a sarcophagus. The liner notes, to me, were no different than hieroglyphics, the album art too allegorical for a twelve-year-old girl who still read (and enjoyed) The Family Circus. But, soon enough, The Who’s Union Jack, and Pink Floyd’s prism, and The Stones’ ubiquitous tongue became my first tattoos—not of the skin, but rather the mind—trademarks seared indelibly into my psyche as the exemplar of musical cool.

At the time, 1984, my world musically and otherwise was still fairly pretty and pink, dominated by Madonna and Michael, Huey Lewis and Hall & Oates, and lots of Billy Joel. All of my outfits matched, I made good grades, I wrote long, unprompted thank-you notes. My first concert was Tina Turner’s Private Dancer. My celebrity crush was Kevin Bacon. For my thirteenth birthday, I didn’t ask for a touch-tone phone like all my friends did. Instead, I requested a sweater that had a panda on it. A sweater. With a panda on it. (Also known as the saddest happiest wish ever.)

But, by my fourteenth year, things began to shift. I was still wearing my retainer as prescribed, but also a pin on my jean jacket that said “Life’s a Bitch and Then You Die.” I had discovered the Violent Femmes at church camp. I’d read the entire Clan of the Cave Bear series, which, if you don’t already know, is loaded with more hardcore Neanderthal nooky than you can shake a caveman’s club at. Blame it on hormones, or blame it on Rio, but by eighth grade, authority suddenly seemed authoritative. I wasn’t stupid, math was. Dark sarcasm was suddenly ALL UP in the classroom.

In retrospect, I think fate was hardening me up, doing the opposite of molting. Because not long after Cyndi Lauper crept out and cynicism crept in, my brother died in a single-car accident during his freshman year of college. We received the phone call at 2:00 a.m. I had profound déjà vu during the visitation receiving line. At the funeral, I forgot Kleenex but didn’t need any anyway as I was too bereft to cry.

In the months that followed, I shrugged off sympathy. I avoided my parents’ pain. I kept to myself with copies of Tiger Beat. When what was left of my brother’s belongings arrived at our house for us to take what we wanted, my sister and I went through the nearly empty foot locker his college had shipped and ended up with a lone pair of hiking socks and a piggy bank. “Where are the cassettes?” I demanded. “Where are the tape cases?” No one knew where they were or what I was really talking about, but everyone surmised they’d been dismantled and split among all the kids in his dormitory. Like sacred piñatas, broken open and devoured by wolves.

At 41, I now know there are many last straws in life, that each chapter of our existence has a breaking or turning point. And in 1987, on the cusp of fifteen, news that I would never have my brother’s Quadrophenia was one of them. It’s a moot detail that I didn’t even know what Quadrophenia referenced or was about or much less sounded like; I’d just seen my brother’s cherished tape deteriorate from devotion. The grim reality that some thoughtless mullet-head was now probably cramming it into a shitty Honda glove box, instead of nestling it inside a velour-lined briefcase, was when the proverbial camel’s back broke. I decided right there and then, in my Esprit stirrup pants and Revlon Silver City Pink lipstick, holding those pitiful hiking socks, to find out what classic rock was all about. It was then that I knew that desperate times did not call for Debbie Gibson.

As fate would have it, the next year I went/was sent/ran away to a boarding school, nine hundred miles north of Kentucky. And for all of the prep school stereotypes that fall flat—everyone is either rich or delinquent—the soundtrack of parentless schooling is all-things classic rock. Maybe it’s because many of these campuses have been around since the British invaded the first time, or maybe it’s because they’re chock full of lichens and fog and stony outcroppings and generalized depression and hastily rolled joints. Regardless, when autumn lasts three months, and winter lasts six, and spring is eight weeks of mud and pneumonia, you spend a lot of time on your school-issue iron bed, staring up at the ceiling and trying to summon the waning god of your youth. Eventually, even the most devout will give in and cover that unresponsive plaster crack they’ve been beseeching with a poster. Maybe of Jefferson Airplane. Maybe Abbey Road. Or, ideally, if they’re really thinking this through: Robert Plant. After a few weeks of looking at him, complete with glowing lion’s mane and bulging Yukon Gold, suddenly unanswered prayers appear otherwise. Not to mention, panda sweaters, much less bras, are ready to be set on fire.

For the next three years, I turned to The Stones when I felt rambunctious, Hendrix when I felt unhinged, Pink Floyd when I was morose, and The Who when I was dramatic. Janis allowed me to be a wreck; The Beatles tidied me up. Traffic made me feel profound. Fleetwood Mac, secure. But Zeppelin? Well, if all the other bands were my life preservers, they were my life jacket. I wore them. I turned to them when I was feeling any and every emotion. Restless? “Ramble On.” Misunderstood? “Communication Breakdown.” Grateful? “Thank You.” Wish you’d been named Tangerine? “Tangerine.” My personal anthem was “What Is And What Should Never Be.” I won’t elaborate too much on the stupefying power of that song, but if you can listen to that on headphones and within seven seconds resist giving Robert Plant your firstborn child, your grandmother’s social security number, and all your panties, well then. Good for you. But I don’t think we can be friends anymore.

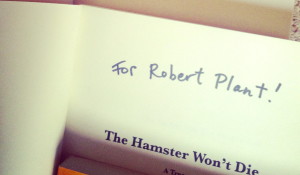

Last year, I cracked a joke on Facebook, wishing I could send Robert Plant a thank-you note. You know, for being such a good spirit guide and all during my high school years. Within seconds, a realtor friend from the general-area-where-Robert Plant-now-lives messaged me with his address. I sat there for a long time and stared at my computer screen. Then I wrote the information on some scrap paper and stared a little longer. You know, just stared. AT ROBERT PLANT’S FUCKING HOME ADDRESS. I had no idea what to do. I mean, these things don’t happen every day to a mother of two who played “The Ocean” to her children in utero. So, I called my husband and asked if he could watch the kids for the next five or six years. Then I paced my bedroom. Then I listened to “Your Time Is Gonna Come” for like six hours. Finally, I wrote Robert Plant a thank-you note. On striped, motherly stationery. I thanked him for being such a nice singer. I thanked him for having good performance skills. I reassured him I wouldn’t show up on his doorstep. My language was so stilted and my cursive so careful, that it may as well have been written by Margaret Thatcher. And then I tucked my letter inside a book of humor I’d self-published (a book with a godforsaken hamster on the cover) and mailed it. And then I waited. Until I realized there was no waiting. I had thanked Robert Plant. That was it. That was what is and what should never be.

For some of us, classic rock will always hold a particular power over other genres. It’s accessible like Top 40, it’s angry like thrash, it’s daring like punk, it’s heartbroken like country. It doesn’t exist just to entertain (like bubblegum) or provide escape (like jam bands), instead rock is cathartic in ways Western and jazz and New Wave will never be. What happened from the mid-1960s to the dawn of MTV was a phenomenon that capitalized on its predecessors, then wrung everything dry for those who’d try to follow. Grunge almost got there again, but it didn’t free people. It flung them straight into the abyss of suicidal tendencies, and then had the audacity to walk away. And today’s music? Well, I’m not a good one to ask. But let’s just say I’m weary of everyone shouting in unison like their Dublin factory conditions have finally gotten the best of not just them, but also their glockenspiels. Honestly, the only modern musician I can look in the eye is Dave Grohl. And also Bruno Mars. And okay, all right, fine. Fine. I just bought Katy Perry tickets.

I do understand that classic rock is overplayed. I understand it’s not an original answer when asked what type of music you prefer. Once you’re past college, you don’t claim Deep Purple as your favorite band; you say something that people can play at dinner parties—at the very least Coldplay, but better yet Adele. I also understand that classic rock was made up predominantly of British bad boys—friends, literally, of the devil; Caucasian posers who plagiarized the American South of its blues before plundering the California coast of its sweethearts. Yet even so, as Stephen Davis writes in his epic Hammer of the Gods: The Led Zeppelin Saga, set against the backdrop of Nixon, Vietnam, and Charles Manson, these “antics were merely the sadistic little games of young English artistes loose in the United States…by the cold light of day they were all really quite nice, even gentlemen.” For better or worse, these pilfering showmen with their inescapable tunes ended up being very likable, very steadfast, and—whether they were pleasuring groupies with dead mud sharks or snorting their deceased father’s ashes—very pardonable.

And good thing. Because out of nowhere this past fall, I got an email from a complete stranger who asked: “Hello there! Found your hamster book in a TX goodwill and bought it. It had a dedication on inside cover. Was curious if it still needs to be given to robert plant?” The title of the email was: “Is this a joke?” But, to be upfront, after the tears and laughter settled, it very well could have been “Celebration Day.”

For some, this might be a sad conclusion to rock star correspondence, but for me, it was simply PROOF of rock star correspondence. Robert Plant had touched my book. He’d skimmed it or tossed it, as he’d done for decades with fan mail, and announced “Rubbish!” or “Ricin!”

Whatever the case, I replied to the stranger: “No. It was actually for him. Thanks for buying it. Hope you enjoy it more than he apparently did. BTW…Did there happen to be a thank you note tucked inside?”

No, the emailer replied. Just a book.

And that was somewhat comforting. Truly.

(Also, I may actually like Jimmy Page the best.)

There’s something to be said for not really knowing your idols. Whether that is your God, your brother, your rock star, or all three. Giving a select few planetary status makes the world big and beautiful and eternal. There is also something to be said for music that stands the test of time. Music so powerful that it can provide buoyancy during tragedy, but so transcendent that it doesn’t become defined by, or remind you of, those circumstances. My drowning days were long ago. I’m a different person, the singers are different people, but the music of that era prevails as excellence, as the paragon of everything rock before and after aspired to be. You probably think I’m just oversentimental, but in my mind, classic rock is rock. It does not move. It does not roll. It takes you everywhere but goes nowhere itself. The song—forevermore—remains the same.

I’m gonna be laughing at “Also, I may actually like Jimmy Page the best” for a long time. GREAT essay.

Thanks for reading, Babs!

Absolutely great! The part about your brother was heart-breaking and your reaction to not having his tapes was perfect. Rock on, Whitney.

(As an aside, my sister recently met Robert Plant and was struck by what a great guy he was, nice, generous, not a dismissive rock-god like she feared. I’m sure your thank you note was well received.)

Thank you, Ellen. I’m going to send your sister my bucket list.

Fantastic, funny, life-affirming.

People who “grow up” and grow out of classic rock probably never properly understood it. Or never really needed it. Worse, they need it, now, more than ever. And it’s too late (Does anybody remember laughter?).

Led Zeppelin, more than all other bands from my youth, remains a life raft, music that does indeed remain the same, and keeps me in the light.

Amen, Sean!

I’ll tuck this in down at the end here so not to be some spotty name-dropper.

Was having some Thai food one day at a downtown dive here in Nashville — no one else in the place when Ol’ Percy drove up in a Lincoln. He came in and ordered, a sweetheart of a guy & quite quite excited about his five dollar plate of peanut chicken. Up close, he looks like a bit like Marty Feldman with excellent hair.

Saw him another time downtown and he smiled and nodded & I nodded back & then thought, “Bollocks, that’s the ole chap that sings Black Dog!”

MY GOD! The Lincoln part is just beyond poetry.

“Music, you now, true music – not just rock n roll – it chooses you. It lives in your car, or alone listening to your headphones, you know, with the vast scenic bridges and angelic choirs in your brain. It’s a place apart from the vast, benign lap of America. ”

Lester Bangs via Philip Seymour Hoffman(RIP!)….but you knew this, natch…

Very nice article. Thanks.

or from the man himself:

So perhaps the truest autobiography I could ever write, and I know this holds as well for many other people, would take place largely at record counters, jukeboxes, pushing forward in the driver’s seat while AM walloped you on, alone under headphones with vast scenic bridges and angelic choirs in the brain through insomniac postmidnights, or just to sit at leisure stoned or not in the vast benign lap of America, slapping on sides and feeling good.

– Lester Bangs

Great story!