Umming and ahhing over the six books my library card allowed then deciding the order for devouring them. Tap, tap, tapping the paper seal on a jar of instant coffee with a teaspoon before finally breaking through and sniffing greedily. Delicately unwrapping the perfect chocolate dome of a Tunnock’s Teacake.

These were the far-from-heady highlights of my 1980s childhood growing up near Glasgow. Zadie Smith, in her essay “Joy” from the January 10 issue of the New York Review of Books, says she experiences “at least a little pleasure every day.” Unsurprising, perhaps, for a healthy, wealthy world-famous writer. But she’s not talking about dusting her awards or pondering her genius. “I don’t think this is because so many wonderful things happen to me but rather that the small things go a long way.”

Indeed they do. Seemingly trivial but secretly significant moments sustained me through a dark decade growing up under Margaret Thatcher, in a coal-mining village near Glasgow that was destroyed by her policies, in a family that was torn apart. I learned to recognise and treasure these quiet, private pleasures. Ultimately, they were life-saving.

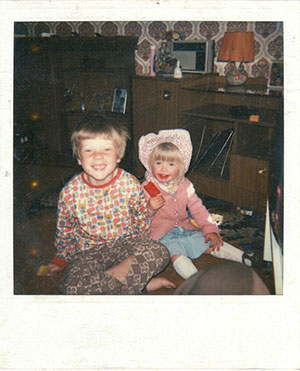

While my mother was in the hospital fighting for her life after a cerebral hemorrhage and my Dad was fighting Maggie to keep the Steelworks from closing, my sister and I were left in the care of our new stepfather, Logan. This was a fight we didn’t ask for and couldn’t win.

It’s quite something to be hated—really truly despised. But once you accept it there is an almost reassuring purity. Maggie knew all about that. She was maybe better equipped to survive it than I was aged 8. Logan ignored my sister, mostly. The target for his hatred was this bookish boy that wasn’t his.

Logan set about making me hate myself before I knew myself. Years before I realised I was gay he called me names in a lisping voice—Jessy, Pussy, Poof. I couldn’t find these words in my dictionary, my most treasured possession. Their exact meaning eluded me but I knew exactly how they made me feel. With our Mum gone Logan made me do all the chores. After forcing me to clean out the ashes of our coal fire with my bare hands and smiling as jewel-red embers burnt to my skin he took to calling me Cinders.

And so I imagined I was in a fairy-tale, fantasised about being rescued—if not by my Mum or Dad then somebody else. Maybe my own Prince Charming. I sought sanctuary in books and libraries. Every second Monday I waited for the local newsagent to open so I could grab the new edition of StoryTeller magazine. The clunk of the cover-mounted cassette in its case promised nearly an hour of stories, a chance to be someone else, somewhere else.

I learned to recognise and accept pleasure whenever I found it or it found me. However small, however fleeting. I prized the skin on school custard knowing Logan never gave us pudding. I went to Sunday School because it was full of stories. I savoured the saltiness of a sachet of soy sauce in the Pot Noodle served by a friend’s mum, recalling it when my mouth was full of blood.

I tried working out a pattern, second-guessing my way to safety, before realizing only Logan knew the rules I somehow managed to break with increasing frequency and ever more frightening results. Bruises were the one certainty and it was my job to explain them away. Not the best reason for starting a life-time of story-telling. But a start.

As an adult, I have built a career around sharing my love for reading and writing. At my Literary Salon I get to talk to the writers who make the stories which take me somewhere else. As a writer I get to be somebody else if I want to. And, if in a library somewhere, somebody chooses to escape into my book nothing could give me greater pleasure. And that’s no small thing.