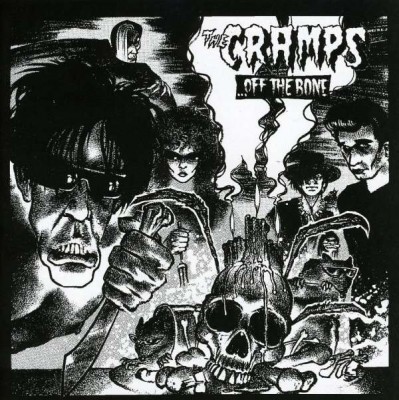

DURING THE CAB ride back to my place I find out that Brett is on drugs: jumping fast between this and other topics, he says he prefers acid to mushrooms, that mushrooms make him feel “murky,” and that he ate mushrooms earlier tonight. By the clock on the cab’s dashboard, it is now four-thirty. “Is there a record player at your house?” he asks, rubbing his head against my shoulder. “I gotta listen to that Cramps song again.” He is talking about the Cramps’ cool-sleazy cover of “Lonesome Town” from their Off The Bone compilation album, which he put on the turntable at Schoolhouse Bar a little while ago while I was ordering a drink. Brett is always doing that, poaching DJ time from me just because he has records with him. He owns over a thousand.

I tell him yes, there’s a record player at my house. We get out of the cab after I pay the driver with part of the money I made tonight. Brett trips on the curb, but catches the light pole before falling down. I let him into the building’s lobby with my key.

“This is really different here,” he laughs, because my building is nice. “I’m used to being around people who live in squats.” He starts to tell a story about the squatters living in his band’s rehearsal studio—which is near here in a location I have never been to that I think must be a secret—then he can’t finish the story because he’s laughing too hard at my lobby. “This is all decorated in here?” he says. “For Thanksgiving?”

We both laugh at what my co-op board has set out in the foyer: bales of hay, toy scarecrows, pumpkins, fake leaves. I say, “I told you it was fancy. Why didn’t you ever want to come over?” I don’t tell him that I’m a month behind on my maintenance payments, or that if I don’t pay my overdue mortgage soon they might foreclose.

“Aw, you’ll like my spot too,” he replies, “when you see it.” He kisses me as we get into the elevator, which is paneled in smooth, tan plastic that’s supposed to look like wood but looks more like brown custard. “Whoa, it’s all pumpkinny pie-y in here!” says Brett. “And so are you!” He points at my orange-tan corduroy coat with brown buttons, like he can’t believe it’s real.

It’s 2008. I’ve owned my current home for ten years—my family put a down payment on the property when I graduated from college, and I pay the mortgage and maintenance. I’ve kept it cozy and habitable, but my struggle to afford its upkeep is evident. The wooden floorboards are buckled with water damage, there’s a tiny stove with clogged pilot lights, a broken window frame, multiple ceiling leaks. Also, I am messy: there are records, sketchbooks, and New Yorker back issues all over the floor.

“You have any roommates?” Brett asks as he crashes into my living room ahead of me and turns on the light. I say no, but that may change soon—to help alleviate debt, I’ve been taking on visiting foreigners, friends of friends, for a month or two at a time. He nods, looks around at my posters and notebooks. “It’s all Amanda-y in here,” he muses. Then he turns on my stereo and starts fiddling with the arm on the phonograph. I stand next to him.

“When you first came in tonight you were smooth,” I say while rubbing his scratchy cheek with my palm.

“Yeah,” he says, grinning. “My beard grows at night.”

“Are you a werewolf?”

“I don’t know. Probably.” He gives up trying to negotiate the record player and turns his face to me. We kiss in front of my stereo, standing up holding each other.

A scruffy rocker type with big sideburns and long black hair, Brett is nothing like boyfriends I’ve had before, and people are always saying he is weird and trouble. I agree with them. Since I stopped seeing him (okay, tried to stop) I’ve become friendlier with Brett’s bandmates, cheerful sarcastic guys who call him Dogboy, than I ever was with him. But whenever I run into Brett, I can’t help being fascinated by his slouching walk, his lazy speech. He says “gotta” and “hadda” and “outta” and does everything to excess, is always smoking and eating.

The first time I ever saw him was six months ago, right after Schoolhouse had hired me, when he came in for a beer before practice. I hugged him and kissed his face—it just felt like the right thing to do, to get physically close to him. “Why do I love you so much and I don’t even know you?” I remember asking him that night.

He said, “Yeah, I got that too.” He bought a mango popsicle at the deli and fed it to me so I didn’t have to touch my records with sticky hands.

Most of us at the bar love each other, even the ones who don’t really like each other; insults, uttered publicly, tend to be mild. In the past six months the owner has lost his father and seen the birth of his second daughter, events which we were informed of via group email the day they happened. We all patronize Joe’s Gourmet across the street, where everyone has a favorite sandwich: the meatball sub, the reuben, the Yankee Special. It’s a subject of perennial debate in Schoolhouse Bar which sandwich is the best.

I adjust the speed on my turntable and Brett drops the needle on the Cramps record. He looks down at me—he’s very tall, a hulk of hair and flesh. “Never noticed how big your breasts are,” he says.

After a few seconds of him staring, I say, “Well, I am pregnant.”

“What? You are?”

I roll my eyes. “Let’s sit on the couch.”

If I were pregnant, I would already have told him, since he is the only one I’ve had sex with all year. Maybe he assumes I’ve been making it with multiple people this whole time—after all, he has been—but maybe he’s just credulous because he’s tripping. We sit together and I swing a leg over his lap. This is not a good time to think about getting pregnant, or to remember that I’m thirty, two years older now than my mother was when I was born.

“Take your bra off and leave on the sweater,” Brett says.

I say, “Not yet. Don’t boss me.”

Schoolhouse Bar, which is not immune to the economic meltdown, has nonetheless become my haven of escape from it, for better or worse. On top of my full-time work schedule, I’ve started to ask for multiple DJ engagements per week, remaining dizzy with exhaustion all day, because I want the twenty dollars the owner gives me at the end of the night. Once home I usually throw my tote bag full of records on the bedroom floor, get in bed with my clothes and shoes on, then wake up to go to work after what feels like one second of sleep—remarkably like Homer Simpson in the episode where he takes an extra job at the Kwik-E-Mart. I’m cutting down on the alcohol, but it is hard to stay away from because for DJs it’s free. Tonight I have had roughly six beers and four shots. At one point I threw up in Schoolhouse’s bathroom and marveled that the liquid was totally clear—my organs had already absorbed all the impurities in Irish whiskey, everything that had made it brown.

A little while ago I was having lunch at a vegetarian restaurant that abides by ayurvedic principles—not because I’m a vegetarian or practice ayurveda, but because I could get a lot of food there for not much money. A woman in a lime-green sweatsuit walked in and started prophesizing, saying she talked to aliens and the aliens had told her the world would be ending soon. “Start buying some canned food,” she said to us all. “Start buying some bottled water.” (Starting that afternoon, I did—for a couple of weeks I bought a bottle of water or a can of food each day and hid them in a corner of my kitchen. It’s all still there, because whenever I feel like using it I tell myself, No, that’s the holocaust stuff.) This woman went up to the restaurant patrons, telling them one by one whether or not they’d fare well in the coming crisis. “You’ll be okay,” she told a few people, adding, “I like your energy” or “You have a nice light around you.” Finally she stopped at my table, considering me. She said, “You might want to cleanse your liver.”

The Cramps perform “Lonesome Town,” Lux Interior singing creepily about buying a dream or two in the place where the broken hearts stay, while I sit on Brett’s lap and unbutton his jeans. Add this makeout experience to the time he and I lay in bed watching PBS’s Learn To Read on his little toaster-sized TV, and the time I fell asleep while Brett looked at comic strips on his laptop with the cracked screen. I was at his place the day he broke the computer, too—it slid off his lap and hit the floor hard, and when he opened it up to inspect it there were jagged black cracks like spider legs in the crystal. “Fuck, I got a problem,” he said. “I was gonna sell this.” There’s a place where lovers go, to cry their troubles away. Near the end of the song there is actual crying.

This song, at once scary and soothing, contrasts with the jangly mania of Bob Dylan’s “Like a Rolling Stone,” which I have been listening to on repeat in the mornings. The Dylan is a trite choice, but feels appropriate—the reproach toward she who used to dress so fine and laugh about everybody that was hanging out, but now has to make a deal with the mystery tramp, never made so much sense.

~

My family have always seesawed between abundance and lack. When I was little, my mother and I walked around the West Village collecting old soda cans for extra money to buy Care Bears and, fittingly enough, Garbage Pail Kids. Then my parents divorced when I was seven and my mom remarried. The new life with my stepfather and little sister became a festival of luxurious food, toys, Nintendo games and trips to our weekend home upstate—I couldn’t tell how hard-won it all was. When I was in tenth grade, my high school lost its funding and shut down. I had been there on a scholarship that would have made my whole high school career virtually free; suddenly, I had to find a new school and my mom had to go back to work. By choice, I went out of town to a boarding school. Then I came back to New York for college and rented my father’s apartment after he, also remarried, moved back to Puerto Rico. The quaintness of downtown in the seventies had turned into glamour, and a Seventh Avenue South address made me feel important, though I shared it with my stepmother’s best friend and almost never left my room. Finally, I realized I’d be happier on my own and moved to where I am now. For a while I lived here with a boyfriend I thought I would marry, until one day three years ago, I realized I wouldn’t.

And the only price you’ll pay is a heart full of tears. I bring Brett into my bedroom. He gets in my bed and watches me take off my pants and put them in the hamper, take my earrings out, brush my hair. When I reach over him to turn off the lamp, he says, “Don’t you have any more girly chores to do?”

Once we are in bed together we begin bickering, albeit good-naturedly. With us it is this way every time: sex is a constant argument over who should do what, why that is necessary, whether we should both just give up and go to sleep. At one point I say he never listens to me (which is true), and his reply is, “Uh-oh, that doesn’t sound happy.” Indeed, the friendly hookup has become unpleasant, a reminder of the strangeness of our lives, or maybe just of how mismatched we are.

He used to show up in Schoolhouse at the beginning of the evening. I’d wait for him right around the time I knew he’d come by. After he had one beer—most nights we didn’t even sit together—he’d hug me and say, “Wait for me, baby, I’ll be back.” Then he would spend an hour or two doing things around the neighborhood, in other bars and at people’s houses. Schoolhouse Bar is in an area where Columbia University’s gentility collides with Harlem’s opportunism in bodegas, laundromats, and check-cashing places, things that look like fronts for other things. He could have been selling possessions, buying drugs, running drugs, or meeting other girls, or doing none of these; most likely he did a typically Brett-like combination of the mundane and the sinister. It was always “I’ll be back” or some variation thereon; for a few weeks he said “I’ll be black,” for instance. He always did come back, but he made me wait a lot.

There was one night when we fought in front of everyone. Before the fight, he kissed the top of my head and said, “Stay there, I’ll be black soon.”

“Good,” I said. “You’ll have a bigger dick and be a better musician.” By the time he returned I was drunk and said I cared about him—not even loved; cared about. Extremely defensive, he said he needed to go think things over by himself, “take his bike out,” and so on. Then he walked away. I cried all night, stumbling around Schoolhouse Bar without him, bumping into everything, until at last I fell and banged my ear against the brick chimney at the back of the room. The next day the ear was bloody and thrumming.

After a long time rolling around in the cold bed we stop. Brett gets up to pee and re-light his cigarette.

“I have to go too,” I tell him. “But you go first.”

He smiles and jokes, “You don’t want us to go at the same time?”

I say, “Maybe I could go in the shower?”

“Good, do that next time and I’ll watch you.” He rumples my hair, then leaves.

Since the summer, Brett has picked up three other women at Schoolhouse Bar while I was DJing, right in front of me. I have been unsuccessfully pursuing my regular grad students and radio hosts, all-American guys who wear glasses. But hard work at multiple jobs has made me too tough, too bitter—at the bar people call me “Amanda man’s-hands.” Still, I’ve held a belief that life is satisfying because I yearn for something, and will remain so as long as I preserve the yearning, the ache. It’s an ache that I suspect would raise contempt in anyone who has known pangs of actual hunger.

In my bed I tuck my knees up to my chest in full fetal position, against the cold, and take deep breaths like a woman in a Lamaze class.

Brett returns from the bathroom and dives under the covers headfirst to start things again. “Stop,” I tell him. “I’m done now. Stop.” He stops and lies down, disgusted, eyes on the ceiling.

“I want to sleep,” I say, more gently. “I have to wake up and go to work, like, so soon.”

He turns on his side, away from me. I get up and use the bathroom. Remembering that I threw up, I brush my teeth.

Not for the first time, I tell myself I won’t go home with Brett anymore. I want to avoid any more bloody-ear incidents, actions that make me feel useless and ashamed. Once I told a friend that the only reason I care about Brett is because I’m scared that if I didn’t he’d be dead—this is a shoddy foundation for a relationship. But mixed with my regret is love.

One day, I tell myself, my life is going to change—I will move, get a better job, have a husband and kids. When that happens, I am going to think about Schoolhouse Bar and miss it. I’ll miss Jason, who brings tubs of popcorn from home on the nights he bartends and serves it to everyone. “I’ve been buying a lot of bulk grains,” he says. “Bulk grains are what’s going to help me eat well these days.” I’ll miss a beautiful girl named Arianna who works as a nanny when she isn’t a “sales associate” in a clothing store. In the daytime I’ve seen her lugging grocery bags, leading a four-year-old child down West End Avenue; at night she shows up in starlet makeup and strapless dresses, passes the DJ booth and kisses me on the cheek, says, “We have to party!” Kevin, the young guy who is both a bike messenger and a clerk at the nearby youth hostel—he parks his bike beneath the sill of the booth, then waits for one of the college-aged French and New Zealanders he just met to buy him a drink. Emy, who leaves at midnight because he needs to get up early to teach martial arts to businessmen. And the sweet, sad man who drives a bus—he is in the bar five nights a week dressed in his MTA uniform, nursing bottles of Budweiser, announcing his plans to move into a bigger place and get a bulldog. We are working hard for our indulgences—like my parents did for most of my life, like Homer did to pay for Lisa’s pony. The difference here is that (with the exception of Schoolhouse’s owner, who supports his wife and children, and a few others) this work is not for our families, but simply for ourselves. These days even buying the Yankee Special for dinner can feel extravagant, but at least we aren’t breaking into our secret stash of water and cans, admitting that the holocaust is now.

When I’m back in bed with Brett I pull the blanket higher up on his body, to cover his white arms and the black tattoos on them. Then I get close to him, rest my face against his back, hug him around the waist. “I’m sorry,” I say. I smell Ivory soap in his armpits, that sharp masculine smell.

“I’m sorry too,” says Brett. “It’s okay.” A little while later he murmurs, “I just thought of Coney Island for some reason.” As we fall asleep I think of it too—of the elevated subway tracks beside the beach, the sudden openness of the city sky.

~

My cell phone alarm wakes me and I hastily get dressed while “Like A Rolling Stone” plays. Brett doesn’t wake up until I come back in the room to tell him I’m leaving; I kiss his temple and say, “Dogboy, I gotta go.” I tell him he can sleep here as long as he wants, and that after twelve noon there will be a doorman downstairs. Later I wonder why I said this, and I feel guilty about it, like I was showing off. There was a brief time before Brett found his new apartment in Brooklyn when he didn’t have a place to live—he was planning to squat in the secret rehearsal space. I’d wished he would ask to move in with me instead, although I don’t think I would have said yes.

“When are you coming back?” he mumbles into the pillow. His dark shiny hair is tangled up, escaping its ponytail holder. His enormous feet protrude from under my pink comforter.

“Not until five or so,” I say, knowing it’s possible he could still be here by then—I have called him at five and six in the evening and had him tell me he’s still in bed. (He watches the five o’clock news in bed before he is fully awake, answers the phone and groggily says, “Did you see the fire?” “Did you see the earthquake?”)

I kiss the side of his face again, a few times more. Rather than lift his head to kiss me back, Brett kisses the pillow, again and again, like a goldfish breathing. As I leave I notice on the nightstand the dish I gave for him to use as an ashtray, one of my Delft china saucers, with the butt and ash in it.

All day long, I imagine Brett waking up and looking around at the pictures hanging in my apartment, of me as a little girl sitting by a pond, me as a toddler holding a kitten. I wonder how long he looks at them. I think: he’s supposed to be with young women in vinyl miniskirts and too much eyeliner, girls on Ecstasy who have clitoris piercings. What use should he have for a pseudo-intellectual with kittens on her wall?

I think about the Cramps, their schlock-horror aesthetic. I always liked “Teenage Werewolf”: I was a teenage werewolf, braces on my fangs. But all in all I never really got into them—I was too busy with classic rock, classic country, classic soul. It occurs to me that one reason I’m not the music fan Brett is, with his thousand-plus records, may be that I know too little of perversity, of alienation.

Mid-afternoon, Brett sends me a text message. “Where are u,” it says.

“Working til 5,” I repeat. “Are you still at my apt?”

He texts, “in studio charging fone I may go 2 bkln and come back”

He doesn’t follow up after that. I get home at around 5:30 and Brett is not there; his records are gone too; the cigarette butt remains in the saucer on the nightstand and later I find another one in the kitchen sink. He has left the light on in the bathroom. He hasn’t made the bed. Finding him gone is more of a relief than a disappointment.

It isn’t until hours later that I go for the off switch on the base of my lamp and find, beside it, a note. Written on the inside of an empty matchbook, the note says,

THANK U Battery dead

4 Everything I’ll call U later

It’s hard to imagine this man is any good—he takes advantage of my pity, living like a drifter, except that drifters actually go somewhere. But I am stuck too, and it’s weird: I’m comforted when I realize Brett may never be gone from me. I sense that, no matter how bad it gets, all of us are going to be okay. For as long as we need to, we will keep finding each other, identifying something familiar there and trying to alleviate it; happy at least for the moment, we will share beer, music, and hot sandwiches. This is a good prospect here in late November, close to Thanksgiving, when it’s so cold and dark.