IN FEBRUARY OF this year, Andrew Stanton, one of the brains behind Pixar’s Finding Nemo and WALL-E, gave a talk at TED called “Clues to a Great Story.” It’s a great presentation—I forwarded the link along and lots of people e-mailed it to me—and you leave it feeling almost ignorant because you haven’t mastered the storytelling fundamentals that he makes seem so simple and self-evident.

It was no accident that Andrew Stanton was speaking at this particular TED. John Carter, his live-action directorial debut based on a series of Edgar Rice Burroughs books, was just a few short weeks from its release. The smart money was on it being a success. Pixar is a national treasure. Stanton is a genius. WALL-E is a nearly flawless piece of art, arresting to kids and adults alike, cruel and funny and for most of it there’s almost no talking at all—but it’s loaded with story, and its payoff (basically, as I read it, that greed is fattening is ultimately ruinous and that love, even among robots, is all you need) is somehow both comforting and traumatizing. Finding Nemo is pretty damn good too, and it channeled money toward Albert Brooks, which is an a priori positive.

Not only is Stanton a TED-approved, master storyteller genius, but one of his co-writers is Michael Chabon, a super-mega-Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist genius, who speaks lovingly about rediscovering the importance of plot in the modern novel! And Disney, the studio, has a lot of muscle, and a long track record of success.

If the movie was a hit, Disney would have a lucrative franchise on its hands—there are thirteen books in the series, and John Carter the character had hung around for decades in comics, TV shows and graphic novels as Burroughs’ son and others picked up the torch.

But John Carter was not a hit. Not even a little bit. It is already being lumped in with some of the biggest busts of all time. The guy who greenlighted it lost his job. Disney expects took a $200 million loss on the movie through March. Two hundred million dollars! Even the company’s stock took a hit.

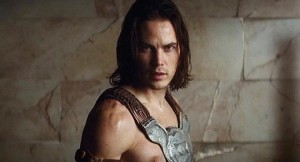

In the “Comments” section under the story where I first got that $200 million stat, someone wrote: “‘Transplanted to Mars, a Civil War vet discovers a lush planet inhabited by 12-foot tall barbarians. Finding himself a prisoner of these creatures, he escapes, only to encounter a princess who is in desperate need of a savior.’ How could that possible fail?” Actually, after watching the movie, I’m not sure I could’ve written that clear a synopsis. John Carter is visually pretty awesome, and its leads are plenty appealing—though its Mars is hardly lush—but it’s hard as hell to follow.

Indeed, the most common complaint has been that the story doesn’t work. The New Yorker called it “A mess.” The Guardian said it was “poorly staged and mind-numbingly tedious.” A guy from the Detroit News sums it up nicely: “Huge bore.” That’s the first sentence of his review, and he’s just getting started: “epically empty,” “the most human-seeming creatures in the film are giant green stick-things with four arms,” “you’ve got to be kidding, right?,” and finally, “one of those films in which a whole lot of nothing that matters goes on in very big ways.” The Portland Mercury had a great line: “Watching the movie felt kind of like sitting in a car while a teenager learns how to drive stick.” (The Portland Mercury, by the way, is the most underrated English-language publication in the world). Willamette Week pans it respectfully (“I haven’t got a clue what was going on, but I’m glad Andrew Stanton’s heart is still in a different place”) but is forced to admit “the plot is nearly impossible to follow.”

The plot is nearly impossible to follow? Really? Hadn’t Stanton declared in his TED talk that “A good story should make a promise. A promise that this story will lead somewhere that is worth your time”? He had!

So what happened here? Is it merely a case, as many have written, of egos run amok? Did Disney just make a huge business miscalculation? Is Stanton’s aversion to what we might call “consumer insights” (“We don’t think about the audience,” he loves to say) at fault?

All of these things probably factored in, but I’d like to take someone else’s $200 million humiliation as an object lesson for my own creative existence. And so, five storytelling lessons that Andrew Stanton, who got a few hundred mil to bring his creative vision to life, can teach us normal folk who just want people to read things we’ve typed:

1. STORYTELLING IS HARD.

The fact that our brains are hard-wired for narrative doesn’t make storytelling easy. We’re wired for love too, and damned if people don’t seem perfectly happy hating each other. And for centuries on end. E.L. Doctorow said, “Writing is like driving at night in the fog. You can only see as far as your headlights, but you can make the whole trip that way.” It’s reassuring to hear that from a great novelist, but in addition to “making the whole trip that way,” you can also a) get lost, b) crash, or c) run out of gas in the middle of nowhere and your phone is dead and the first person who stops to help you isn’t at all friendly. Good storytelling is usually the result of clear but obsessive focus, a little luck, and genuine sympathy for the listener. Stanton obviously has the first, but the fact that he’s so uninterested in the third (I don’t 100% believe this, but he keeps saying it) tells me he’s had lots of the second. A ton of storytellers seem to be waiting around for #2 also, but end up stepping in, well…#2.

2: BEWARE OF THE STORY ABOUT YOUR STORY!

One of the debates over the John Carter corpse is whether or not it was marketed correctly. From an article on vulture.com: “Stanton, who also nixed all mentions of his Pixar work in the teaser for fear that people would think this film was for little kids, was working from the belief that John Carter was as universally iconic as Dracula, Luke Skywalker, or Tarzan. He believed that audiences would gasp in delight at John Carter’s very appearance in much the same way that a Batman teaser might only need to flash the Bat Signal. ‘To him, it was the most important sci-fi movie of all time,’ recounts one Disney marketing insider present for the pitched battles. But people don’t say, ‘I know what I’ll be for Halloween! I’ll be John Carter!’” The marketers got lost in an argument about whether to market to kids, fans who loved the original novels, women (more inclined to respond to the romance), general audiences who like a good adventure—and consequently no one was really dying to see it. I have a 9-year-old son, who I thought I might take to a second viewing, but it would take me longer to explain the plot (to say nothing of all the swordplay on a planet with airplanes and guns) than it would take to sit through the movie again. Not a good situation for a movie with a bloated budget and no big stars.

3: THIS SHIT IS ART, MAN!

Any art you try to sell is a “product,” and any product, beautifully made, is “art.” But if you’re in the business of producing art in the hopes of sales (movies, music, books, big beautiful paintings), you just never know. His Greatness Paul Weller once explained away a bad album by saying “Sometimes it’s hard to know when you’re making shit.” (This is “Cost of Loving” era…) Ain’t that the truth. The only comfort here is to remember that we’re not generating commodities whose value is only determined by someone’s ability to make them cheaply and sell them for more than that. Creative people—writers, filmmakers, potters—make art. The art market is unpredictable.

4: EVEN THE BIG ONES FAIL SOMETIMES.

As obvious as this is, it’s still comforting. But while remembering it, we shouldn’t consider it fluky. Andrew Stanton probably failed with John Carter because he stopped listening to people, was adrift from the Pixar team that had helped him with previous masterpieces, and believed things about the story that were just plain wrong. I love this line from one of the articles on the film: “Stanton joked that before he started working heavily on John Carter, people had to prove that they were die-hard Edgar Rice Burroughs fans.” Really? Why? (You know he wasn’t “joking,” either.) A genius head up a genius ass is still a head up an ass. (Been there too, but without the genius part.) When I read that quote from Paul Weller years and years ago, I thought “How couldn’t you know? You were clearly untethered from all the influences that make you awesome, and you couldn’t tell you were making shit? I could tell, and now I’m out $16.”

5: FRANKSTEIN’S MONSTER WAS CALLED A MONSTER FOR A REASON.

Here’s a paragraph from an article on Michael Chabon’s involvement in the “John Carter” script:

Luckily, by the time Chabon came on board, Stanton and his writing partner Mark Andrews had already done a lot of the heavy lifting. They’d already figured out much of the structure of their movie, including lifting some stuff from the second and third books to shore up the first. They’d combined a few characters, and gotten rid of sequences which would have cost too much or made no sense. The main thing they wanted Chabon’s help with was strengthening the characters—including making John Carter a relatable protagonist, and making Dejah Thoris a well-rounded enough character.

Hmmmm. If you’re jamming other books into your story, combining “a few” characters and just not bothering with whole sequences because they might cost too much (bear in mind that these books are good enough to still have devoted fans after being around for about…100 years)—and you have access to one of America’s best novelists…maybe you should have the novelist help do more than round out a couple characters. (The fact that that paragraph begins “Luckily” also tells you a little too much about its writer.) If you have a good idea (like re-telling a kickass story of a Civil War veteran who’s transported to Mars to do more ass-kicking), be true to it. If the idea is Romeo and Juliet and you think maybe you could punch it up by adding a little Midsummer Night’s Dream and throwing in some Macbeth just for blood and maybe not using Romeo’s best friend because he’s a drag and having Michael Chabon give Juliet some better dialogue…you’re probably wrong.

~

Andrew Stanton will ride this out. Ishtar always comes up in any discussion of monster movie flops, and it starred Warren Beattie and Dustin Hoffman, whose careers carried on just fine. No one looks at J. Lo and thinks Gigli.

Stanton got lost in a big, complicated forest of a story, and you sense that at some point while he was trying to follow his own breadcrumbs back to the main trail, he knew he was in trouble. Then he ran out of breadcrumbs. We’ve all been there. That Andrew Stanton has, too, proves that it happens to the best of us.