IN COLLEGE I had only one friend, Max, who wasn’t a fan of the Billy Joel Medley.

I will explain: in a fit of creativity—the kind of idiot-genius creativity you have a lot of when you’re 20—I once spent an afternoon in front of my stereo recording snippets of Billy Joel’s Greatest Hits (vols. I & II) so that all the “whoa”s were together, all the “oo-ooh”s were together, and so on. I cut up “Movin’ Out (Anthony’s Song)” so that the ackackack part lasted 60 seconds; I remade “Scenes From an Italian Restaurant” to mention the bottle of red and the bottle of white twenty times in all imaginable combinations. The phrase a bright-orange pair of pants, from “It’s Still Rock ‘n’ Roll to Me,” became every other line of the song: What’s the matter with the car I’m driving / And a bright-orange pair of pants / Should I get a set of white-wall tires / And a bright-orange pair of pants. The result became a popular party tape, not by any definition a masterpiece but probably still the most-beloved thing I have ever made. So I was surprised, even hurt, when I heard Max denounce it.

He was a sweet, sensitive friend of the extremely close type, again, that most people stop having when they pass 20. An intellectual and a sophisticate, Max liked complex music that I didn’t have the patience for. We’d go to jazz clubs. In his dorm room and later his apartment, he’d ask me to listen to CDs by the likes of Philip Glass, the Kronos Quartet, and Medeski Martin and Wood. And one night, after being subjected to the Billy Joel Medley for what must have been the fiftieth time, he exploded with frustration: “Why does music always have to be a joke to you?”

A fair question. Years later, I realize he hit the nail on the head as regards my tendency to sneer at music. I’m an inveterate fan of parodies and an even bigger fan of outright mockery, in all forms of culture but in music especially. This may be because music is strange—maybe I don’t completely understand what about music makes it so great, so I try to belittle it, like a playground bully does a smart kid. Latching onto what makes bad music bad is way easier for me than trying to identify the many individual merits of good music. This exposes an ugly side of my character, I allow that. But I don’t think anyone’s joking about music means they don’t love it.

My Dick, my new favorite “band,” are a duo whose songs are careful recreations of Top 40 hits replacing key phrases with “my dick.” That’s the sole conceit, and they see it through across Hall and Oates, Bruce Hornsby, Alanis Morrissette, Van Halen, and John Lennon with an equal degree of dedication. Listening to the double album (23 songs!), one can tell that somewhere along the way this act of disdain became something more noble. In order to do it right, they must have spent plenty of time deciding which songs would work best in the format. Each song had to have a proper balance of “my dick” with the rest of the lyrics. All the “my dick”s had to make sense within the phrasing of the song, in scansion though not always syntax. (The nonsense aspect to My Dick is often delightful. Consider their version of the Spin Doctors’ “Two Princes”: My dick my, or my dick me / My dick mydickmydickmydick can’t you see…) Most importantly, they had to learn how to play the songs, walking a mile in the shoes of pop stars both revered and hated. So, yeah, it’s a joke. An elegant one that really works.

Another duo that used elegant mockery was Ween, for my money one of the best bands of all time. Middle-school friends who made music together from 1985 until 2012, Gene and Dean Ween turned jokes into songs and vice versa. They put on the voices of different characters, experimented with speeding up and slowing down tracks, made many drug references, recorded chainsaws and answering-machine messages. As artists they were too talented, too wise, to let the jokes stand on their own so they labored to enhance them musically. For 12 Golden Country Greats, for example, they worked with seasoned Nashville musicians to pull off a country album that sounded letter-perfect, from jaunty harmonica on the breakup song “Piss Up a Rope” to mournful pedal steel on a song about a dog named Fluffy who chewed his leg. Then there was their album The Pod, whose gloomy, murky sound makes sense considering the two made it when they were quarantined together with a case of mono. In listening to any of Ween’s albums, as intricate and satisfying as they are, it would be hard to deem them ‘serious.’

The same can be said of the enormous catalog of the Frogs, brothers who combined fascinating arrangements with gleeful vulgarity at which it’s impossible not to die laughing—if, of course, you’re into that sort of thing.

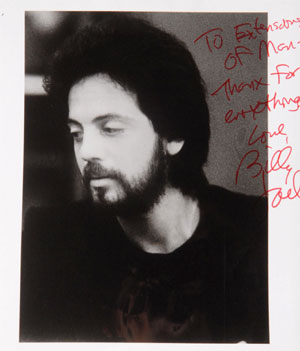

So many of us who consume pop culture—though not all—are terminally wary of anything too earnest or sacred, anything that gets placed on a pedestal. No sooner does it become mildly popular than it becomes ripe for satire. It’s a huge relief, then, when the earnest thing is sent up: making fun of it has transformed it into something good again! These days I tend to hear Weird Al Yankovic’s version of any giant hit before I hear the real thing, and I know this is a function of how I’ve chosen to live, the music-consumption choices I’m free to make now that I’m not 20 anymore. Which reminds me to ask: is Billy Joel even a relevant target in 2013? Does he inspire as much sarcasm among people who are sick of him as he used to in 1997? Just the other night I was at a bar where Billy Joel videos were being played on a TV screen—including the late-period tune “River of Dreams,” which has a video of Joel, decked out in suit and black sunglasses, and his team of backup singers dancing in place on a dock. I thought of my and my college friends’ alternate lyrics to that song: In the middle of the night / I go walkin’ in my sleep / I drop my trash off at the curb / Make sure I’m parked legally…[etc.]

Max was right to sound the alarm all that time ago. Since then, rather than be ashamed, I understand music as something it’s OK to laugh with or even at; that is, something that inspires joy. I’m on about my tenth go-around listening to My Dick’s double album all the way through. By now, even though I’ve memorized some of the songs, my joy hasn’t diminished. I find myself singing Sting and Enya, albeit in My Dick style, to myself as I wait to get to my destination on the subway—something I thought I’d never do again. Yes, it is a joke to me. Here’s to getting the joke.

The My Dick sessions obviously required a lot more work than one would think by a cursory listen, which Amanda acknowledges. It was a weak idea—a lame one, in fact—but in the execution it was elevated to entertaining art of the lowest brow. I just wish they’d hired a graphic designer who could have devised a better logo.

A friend told me he was delighted that it was just a picture of a T-shirt. Thanks so much for the comment and support!

Musical tastes are such a tribal thing, especially when you’re young, and it often seems as if the alternative music scene is united more by the music it hates than the music it loves. When you’re in college, you’re surrounded by bad music, in the dorms and frat parties. Taking the piss out of a pretentious songwriter feels like a way of opting out of the herd.

Parody is a powerful thing, whether silly or cutting. Roy Orbison’s publishers sued Two Live Crew over a parody of “Oh, Pretty Woman”, and the case made it all the way to the Supreme Court. Even Weird Al has been refused permission by a number of artists to parody their work, even though his parodies are usually pretty affectionate. (One of the artists who refused? Billy Joel.)