Over the next month (well 6 weeks) we are excerpting Tessa Laird’s astounding book A Rainbow Reader. Released in New Zealand and difficult to find here in the US, the book takes apart the social history of the spectrum, from the personal to the political getting at the red heart of color and its cool blue center going from Karl Marx to William Gass and William Burroughs, via art, war and psychedelia.

HOW TO BEGIN talking about color, and not just any color, but this excessively emotive color? Where on earth to begin with red? In earth? The first color of the spectrum is also that of the base chakra, the ancient Hindu “subtle system” of points on the spinal column which relate to different colors, moods, attributes and powers. Kundalini is a coiled serpent, dormant at the base of the spine. Once awakened, she travels through the seven centers, and human potential is fully realized. Muladhara is the first station Kundalini passes through on her ascension, and this, the red, root chakra, relates to issues of security and sexuality.

Starting in red and slowly uncoiling ideas like the rainbow serpent that is Kundalini, I hope to achieve, if not enlightenment, then some sense of awakened attention and purpose. Following the rainbow template, which also corresponds to the trajectory of the chakras, I will explore the colors one at a time. Perhaps this sequential dance in six chapters will become the literary equivalent of that Orientalist cliché, the dance of the seven veils.[1] I know this much already, that the East, its tropes, and the West’s use and abuse of those tropes, will weave in and out of these essays like the reedy sound of the nay flute, to which hips and cobras alike have swayed for millennia.

~

It used to amaze me that the light of our sun, clear and bright, when filtered through the flimsy layer of my eyelids became a rich scarlet, as though I’d just buried my face in crimson velvet. How was this possible? And then it dawned on my young mind that I was red inside! The whole of my interior was coursing with this opulent substance, the recognition of which is perhaps the originary aesthetic awakening of every human being. From the dark womb our first encounter with light must be mediated by these, our eyelids, not to mention the bloody mucus we come wrapped in. Red, I realize, is about labor in all its guises. Birth and color. I have a story to tell about this.

When I was a girl, I visited my father during school vacations. He owned some flat and desolate land outside of Dargaville, in what seemed like the dreariest spot of the North Island of New Zealand. My father had visions of a bounteous organic orchard run by himself and a bevy of international beauties in various states of undress, but the reality was, in fact, a very lonely one. Often, I was the only other human he would see for months. The orchard was never large enough to become a going concern, though it produced far too much for one man to consume alone. He ruined his teeth eating fifty pieces of fruit a day.

He was vegetarian but not an animal lover, grazing cattle on his property to make a few extra dollars even though most of these beasts were destined for the meat works. Once he had a pregnant cow, and early one morning, he helped deliver her calf. He woke me up, full of excitement for me to see the unsteady new creature in the fresh morning dew.

My father was a perennial morning person, while I was skeptical about anything to do with farming at any time of day. I was a city girl and a bookworm and hated having to muck in with gardening and chores, so I was less than joyous to be shaken out of sleep and into my gumboots in the chilly air and wet, tangled grass.

I can’t remember if the calf had the patches of a Friesian, if it was chocolaty, or a honey-colored Jersey. But I was absolutely transfixed by the afterbirth steaming in a huge pile in the grass, as though aliens had just landed and left something utterly foreign on earth. It was translucent and opaque, gelatinous and covered in rainbow swirls, and I swear there were colors in there I have never seen before or since. It was like looking into the eye of a nebula and I felt, right then, that this was divinity, what Hindus call darshan, or looking into the eye of God. Like when the baby Krishna ate mud and his mother made him spit it out, and she looked into his mouth and saw the universe. Perhaps it is no accident that cows are sacred in India, or that Krishna is the cosmic cowherd.

~

But wait – I remember something else now, which preceded and presaged the alien visitation of the placenta: a drop of blood under a microscope. It was when I was five and played with Gabriel White who lived around the corner from me in Ponsonby, an Auckland suburb full of yet-to-be-gentrified Victorian weatherboard houses. His older brother had a microscope – the pinnacle of sophistication – and I was so flattered when he invited me to peer through it! But my reaction betrayed my youth: I simply couldn’t believe that I was looking at blood, because everyone knows that blood is red, and what he showed me was a psychedelic mosaic of colors on the glass slide.

Blood carries our DNA, and the double helix can be seen as two intertwined serpents. Jeremy Narby suggests in The Cosmic Serpent that in ayahuasca-induced trances, these microscopic snakes that live inside our bodies and make us who we are, present externally as giant, multi-colored boas and anacondas. Then there is the Australian aboriginal Rainbow Serpent and Quetzalcoatl, the Aztec feathered serpent (shimmering with the rainbow of iridescent feathers of the jungle), not to mention the Kundalini serpent and her rainbow trajectory through the chakras. Perhaps rainbows exist in our teeming wet insides as much as they do in our stormy, scudding skies.

~

I’m not the first to write a love letter to a color, to press my thoughts between sheets of paper only to find that – like Rorschach’s blots – they have grown teeth, wings and tongues. William Gass wrote a little book about big things, like language and literature and the color blue.[2] Alexander Theroux filled two books with galloping, attention-deficit disorder essays on colors, rattling off every possible chromatic factoid he could muster: they are coked-up and kaleidoscopic.[3] Anthropologist Michael Taussig broke my heart by writing the book on color I was planning to – he must have read my mind.[4] But filmmaker Derek Jarman’s is the most moving tale of all – he wrote his paean to color as he was losing his sight from AIDS-related complications:

I wrote this book in an absence of time. If I have overlooked something you hold precious – write it in the margin. (…) I had to write quickly as my right eye was put out in August … and then it was a run-in with that dark. I wrote the red on a hospital drip, and dedicate it to the doctors and nurses at Bart’s. Most of it was written at four in the morning, scrawled almost incoherently in the dark until sleep blissfully overtook me. I know that my colors are not yours. Two colors are never the same, even if they’re from the same tube.[5]

~

Red is for labor. I was born at home, in a very small house in bush-clad Titirangi, the belt of forest to the west of Auckland. The midwife took my afterbirth for her rhubarb patch. I always loved the idea that the bloody package that had sustained me was transmuted into ruddy stalks of rhubarb. Māori have the same word for afterbirth as for land, whenua, for the two are indivisible; the place where your whenua is buried is your whenua. Dust to dust. Everyone, it seems, was made from clay.[6]

~

In an essay simply titled Red, Alexander Theroux drops into his whirlwind of references that the Māori possess hundreds of words for the eponymous color.[7] This was news to me, and I doubted his scholarship, particularly since in another passage he spelled pohutukawa “pahutukawa.”[8] Then I came across William Colenso’s 1881 pamphlet On the Color Sense of the Māoris in which the eccentric but learned missionary discusses the superior sense of vision of Māori at the time of European contact. One example among many is their ability to discern Jupiter’s satellites without telescopic assistance.[9] Colenso’s lyrical writing evokes an era in which the subtlest variations of hue are matched with intricate language; a poetry of the everyday. When the white man introduces blue cloth, Māori invent a raft of terms for its many subtle shades. Colenso laments that European colonists or Pakeha encouraged Māori to use only one word to cover this gamut of blues: the clumsy transliteration pimru.[10] But it is about the color red that Colenso has the most to say:

In nature around them, they saw plenty of a red color, – in the rainbow, and in the gorgeous hues of the clouds at sunset; in some of their birds, – as in the red beaks and feet of the pigeon, the oyster-catcher, and the blue swamp-hen, and in the red features of the large parrot, and on the heads of the two species of parakeet; in their fish, – as the red gurnard, the snapper, and the crayfish; in many of their seaweeds; and in the flowers and small fruits of several trees and shrubs.[11]

The appendix to Colenso’s slim volume is the mother lode for hunters of red. Here is proof that Māori did indeed have hundreds of words for red (well, at least 83). They run the gamut from pure, clear, strong and brilliant (Tino kowhero, Tino whero rawa, anana!) to lighter, but fair reds (Kowherowhero,Wheronga-parakaraka); from the fainter (Maa-whero, E iti ana tona whero, Ahua whakawhero noa iho) to dark red, red-brown (Whero-pakaka, Whero-tangi-kee). He ends with faded red (Whero haamaa, Wherowhero tupapaku) and ugly, disagreeable red colors (Whero kino, Whero marutuna).

This intricate, joyous differentiation has been standardized to plain old whero, while the majority of Māori whakairo, or carvings, have been covered in “Museum Red,” an unforgiving house paint somewhere in the spectrum between bricks and fake blood. At some point in our fledgling history, museum staff saw fit to cover every carving with this deadening concoction, regardless of its original hue. For such a prevalent practice and well-known term (at least in art and museum circles) there is surprisingly little written about Museum Red. I have heard anecdotal stories that it was instituted in order to preserve, to standardize, even to spruce-up for an impending Royal visit. But no one seems to know for sure just how the practice got started, and if it was a Māori or Pakeha innovation.

These days the redwash of Museum Red is being stripped off carvings to reveal that some of them are beautifully polychromatic, like the meetinghouse Hotunui, whose complex patterns in ochre, white and black are on view in the Auckland War Memorial Museum. And yet, truth remains, red ochre was standard for most Māori carvings, and Museum Red, crude as it now seems, was the contemporary, durable update for the natural pigment that most resembles blood, for wharenui, carved houses, are living ancestors built of blood.

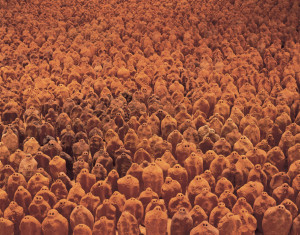

D.H. Lawrence writes of Ancient Etruscan diviners, to whom “the blood was the red and shining stream of consciousness itself.”[12] British sculptor Antony Gormley, like the Etruscans and the Māori, has a mystical approach to the red stuff. Gormley won the Turner Prize in the 90s for one of his famous Field formations. He’s made them since 1991 and continues to do so, or rather, employs people to make them for him. The first version was made by an extended family of brick makers from Cholula, Mexico. To this day each maker is given a hunk of clay and instructions to fashion a simple human figure that fits in the hand. The figures don’t have limbs or features, and each is unique, but they are made to stand en mass, gazing at the viewer like hoards of Lilliputians, souls of the dead or of the unborn.

Gormley uses clay that would otherwise be turned into bricks. So, in a way, Field is a liberation of formless matter that would have been cut into blocks and used to build walls, that symbol of construction that erases traces of humanity and our connection to that earth from whence we cut the clay.

Antony Gormley, American Field, Installation Salvator Ala Gallery, New York, 1991. Courtesy of the artist.

~

Ka: Stories of the Mind and Gods of India is Roberto Calasso’s retelling of the mythologies of Ancient India. In the primordial beginnings of the city-state, the children of the creator God labor to create meaning by building a giant bird out of bricks.

Brick, they said: citi. Bricks in layers. But what is citi? It’s cit, which means ‘to think intensely.’ Every brick, baked and squared, was a thought. Its consistence was the consistency of their attention. Every thought had the outline of a brick. It wouldn’t disappear, wouldn’t let itself be swallowed up in the mind’s vortex. Rather it became something you could lean on. Something you could place a next thought on – and slowly, crisscrossed with joints, a wall was raised. That was the mind, that was the body: the one and the other rebuilt, with wings outspread.[13]

Gormley has long planned a giant man made out of bricks, although I’m not sure if this colossus would be a statue, or a habitable building. I find it compelling that the rectangular module of the brick might eventually ape the form of its creator. New Zealand potter Peter Lange has made many things from bricks – teapots, garden seats, tents, an airbed, and even a functional boat. Someone told me at a dinner party that Peter had quipped, “If the boat floats, it will be called craft, but if it sinks, it will be called art.”

Lange is the brother of the late David Lange, New Zealand’s enormously popular Labour Prime Minister from 1984-1989. Red is for Labour, and back then the Labour logo was the letter L made from three red bricks on a white ground. My mother once baked a rather hopeful “Labour” cake on election night, with white icing and red L laid out in glacé cherries. Labour didn’t win that time, but there was much jubilation when Lange took the next election. We were just as ecstatic when he won the Oxford Union Debate against nuclear proliferation. We were so in love with Labour’s foreign policies, we were practically blind to their neo-liberal fiscal policies. They were selling off state-owned assets left, right and center, destroying local industries, including homegrown ceramic production. Lange, the potter, watched Lange, the politician, try to reign in the juggernaut unleashed by his own cabinet, but it was too late. In 2011, Labour campaigned with bright red billboards to “Stop Asset Sales,” but the country didn’t care, voting instead for a blue-clad banker as the world’s financial markets collapsed around his smug grin.[14]

Potter Peter Lange and his (potentially) sinking brick boat, that, in fact, floated…

~

In 2010 I attended a Das Kapital reading group. Working slowly through Marx’s brick of a book, bound in revolutionary red, I came across this:

A classic example of over-work, of hard and unsuitable labor, and of its brutalizing effects on the worker from his childhood upwards, is afforded not only by coal-mining and mining in general, but also by tile and brick making, in which industry the recently invented machinery is, in England, used only here and there. Between May and September the work lasts from 5 in the morning till 8 in the evening, and where the drying is done in the open air, it often lasts from 4 in the morning till 9 in the evening. Work from 5 in the morning till 7 in the evening is considered ‘reduced’ and ‘moderate’. Boys and girls of 6 and even 4 years of age are employed. They work for the same number of hours as the adults, often longer. The work is hard and the summer heat increases the exhaustion. In a brickfield at Moxley, for example, a young woman (24 years old) was in the habit of making 2,000 bricks a day, with the assistance of two little girls who carried the clay for her and stacked the bricks. Every day these girls carried 10 tons up the slippery sides of the clay pits, from a depth of 30 feet, and then for a distance of 210 feet.[15]

Reading such tales of woe in the past tense is easy, and it takes mental discipline to transpose these horrid scenarios onto today’s sweatshops in the great global “elsewhere.” In attempting to unravel the mysteries of madder-red Persian carpets, journalist Brian Murphy travels through Iran and stumbles across a small workshop where two brothers, aged seven and ten, work on a loom.

The pattern they were following – a classic Herati – came from a scrap of paper torn from a magazine. A clock on the wall loudly ticked each passing second like a musician’s metronome. The boys were tying and cutting the knots at about the same tempo.

Their boss, Abdulmanon, kept watch. The wool was factory spun and chemically dyed. ‘So?’ He shrugged. ‘You really think anyone cares? This is a business, not a museum. We need to make money.’[16]

Assuming the Westerner is more disturbed by chemically-dyed wool than poor labor practices, Abdulmanon rails against Western purists who prize authenticity above pragmatism. These purists are at least partly to blame for the child labor that produces hand-woven masterpieces, stained, naturally or unnaturally, in blood red. But perhaps I am using my own bleeding heart to interpret this scene, to pass judgment on what appears to be exploitation. Maybe I don’t understand this world, its prayer or its labor, its blood or its carpets. One of the carpet-sellers poses rhetorical questions about time and labor, providing a red thread for Murphy to weave through his text:

‘Time is something man created to bring order. Am I right? We are the ones who long ago sliced it up into hours, minutes, days. Are these pieces the same length for all? Yes, that is true, you could answer. But think again. It is not true at all. Is an hour praying the same as digging a ditch? Is an hour making a carpet the same as an hour making bricks?’[17]

~

In My Name is Red, Orhan Pamuk tells a bloody tale of murder among Ottoman miniaturists. The story unfolds from multiple points of view – even the color red becomes the narrator of its own story, enumerating the occasions it has appeared in miniatures throughout Ottoman history:

I embellished Ushak carpets, wall ornamentation, the combs of fighting cocks, pomegranates, the fruits of fabled lands, the mouth of Satan, the subtle accent lines within picture borders, the curled embroidery on tents, flowers barely visible to the naked eye for the artist’s own pleasure, blouses worn by stunning women with outstretched necks watching the street through open shutters, the sour-cherry eyes of bird statues made of sugar, the stockings of shepherds, the dawns described in legends and the corpses and wounds of thousands, nay, tens of thousands of lovers, warriors and shahs.[18]

Having established its primacy, Red attempts to define its own essence: “I’m fiery. I’m strong. I know men take notice of me and that I cannot be resisted. (…) Wherever I’m spread, I see eyes shine, passions increase, eyebrows rise and heartbeats quicken. Behold how wonderful it is to live! Behold how wonderful to see. Behold: Living is seeing. I am everywhere. Life begins with and returns to me.”[19]

Red is at pains to explain the laborious process by which it was created, from crushed dried beetles and other exotic substances, as well as the anticipation it felt sitting quietly, maturing in the pan for days. But Red speaks to us, the reader, not to the two blind miniaturists debating its nature, as if it couldn’t talk:

If we touched it with the tip of a finger, it would feel like something between iron and copper. If we took it into our palm, it would burn. If we tasted it, it would be full-bodied, like salted meat. If we took it between our lips, it would fill our mouths. If we smelled it, it’d have the scent of a horse. If it were a flower, it would smell like a daisy, not a red rose.[20]

The English critic and novelist John Berger writes about red, and also chooses an unlikely narrator – a dog – who tastes and smells meat, metal and flowers, just like Pamuk’s blind seers:

5.30pm

Red, Vico told me one day, is the color of sacrifice. Really?

Both pain and triumph, he said, are in the color red, and of course blood. Blood isn’t a color, it’s a taste, I growled.

Some reds are killing, others are healing, he went on, the abattoir and the geranium, King. Sometimes I’m sorry for Vico; sometimes I believe Vico has gone mad. Geraniums smell of wet silver, I said to tease him, go and sniff them in the cement coffins by the traffic light.[21]

Pamuk’s master miniaturists disdain the Venetian method of using a variety of red tones. So much for the acclaimed abrash or differentiation in Persian carpets; in miniature paintings, red must be celebrated in all its purity. “Besides,” he wrote, “we believe only in one red.”[22] William Burroughs would have called this logic a relic of the One God Universe or OGU. It is, I think, the same logic that had Frank Stella celebrating paint straight out of the can. Allah be praised, purism turns up in the strangest of places.

~

So many contemporary artists work with ideas of labor that curator and critic Nicolas Bourriaud despairs of the “conceptual hacks” who, for a show in the nougat-producing region of Montelimar, “laboriously ‘associate’” nougat production and unemployment figures.[23] The Mexico-based artist Santiago Sierra pays day laborers minimum wage to perform distressingly menial tasks, like crawling around and shining shoes at an exhibition opening, or sitting inside a cardboard box for hours on end. Most notoriously, he had lines tattooed on the backs of desperate workers and drug-addicted prostitutes in Havana, Cuba, for the price of their next fix. Sierra deflects accusations of exploitation by pointing out the invisibility of the conditions he makes visible with his uncomfortable works.

In a more utopian gesture, the Puerto-Rican artist Beatriz Muñoz consulted with local factory workers, asking them to suggest group activities they would enjoy during break time. She negotiated with the employers for these suggestions to be built into the schedule. Games and competitions became part of the working day, as well as this beautiful idea: workers took a unilateral break to watch the sunrise together outside the factory – pink, like the faintest whiff of socialism.

Artist Beatriz Muñoz’s work included an intervention where factory workers got to watch the sunrise.

~

If red is the beginning of colored experience, does it have an end? Like a Chinese knot made of red brocade cord, which weaves in and out, is there one red thread that weaves through all our experience, which takes us somewhere, and leads us, inexorably, on? Perhaps, like the Chinese knot, red just turns us in on ourselves, because that flashiest of colors is also what colors our interiors – politics aside, we are all red on the inside. Like Dorothy clicking her ruby slippers at the end of The Wizard of Oz, it’s the color that takes us home.

Click your heels together three times and say, “There’s no place like home.”

Next week in Part II, Tessa Laird tackles Orange, with A Tiger’s Leap into History.

[1] There are seven colors in Newton’s version of the spectrum but only six in contemporary science. I chose modernity over whimsy (shock!) and put Indigo into the Blue chapter.

[2] Gass, William, On Being Blue: A Philosophical Enquiry (Boston: David R. Godine), 1976.

[3] Theroux, Alexander, The Primary Colours: Three Essays (London: Paparmac), 1994, and Theroux, Alexander, The Secondary Colours: Three Essays (New York: Henry Holt & Co.), 1996.

[4] Taussig, Michael, What Colour Is the Sacred? (Chicago: University of Chicago Press), 2009.

[5] Jarman, Derek, Chroma: A Book of Colour, June ‘93 (London: Century), 1994, 42-43.

[6] “In the original hieratic language, the first human, the interpreter of all that exists and the giver of names to all corporal beings, is called Thoth. The Chaldeans, the Parthians, the Medes, and the Hebrews call this being Adam, which means ‘virgin earth,’ and ‘blood red earth’ and ‘fiery red earth,’ and ‘fleshly earth.’” Lévi-Strauss, Claude, The Savage Mind (Chicago: University of Chicago Press), 1966, 145.

[7] Theroux, The Primary Colours, 163.

[8] Ibid, 245.

[9] This was also noted by Charles Darwin in his Beagle voyage regarding the indigenous people of Tierra del Fuego. Michael Taussig problematises this assumption of indigenous visual acuity by linking it to other essentialist characterisations, in Mimesis and Alterity: A Particular History of the Senses (New York: Routledge), 1993, 81.

[10] Colenso, William, On the Colour Sense of the Māoris (Christchurch: Kiwi Publishers), 2001, 21.

[11] Ibid, 17-18.

[12] Lawrence, D. H., Etruscan Places (London: William Heinemann), 1932, 98. Compare this to the words of a scientist, who says, rather pragmatically, “The iron in blood imparts a red color, but its purpose is only to collect oxygen molecules. The red color is immaterial, since it is not observed from outside the body (nor is the blood naturally reached by sunlight to fuel the red color).” Parker, Andrew. Seven Deadly Colours: the Genius of Nature’s Palette and how it Eluded Darwin (London: Free Press), 2005, 147.

[13] Calasso, Roberto, Ka: Stories of the Mind and Gods of India (New York: Vintage/Random), 1999, 34.

[14] In spite of the U.S.’s peculiar politico-chromatic reversal, the color red symbolizes socialism, and blue

conservatism, in most of the rest of the world.

[15] Marx, Karl, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books; New Left Review), 1976, 593.

[16] Murphy, Brian, The Root of Wild Madder: Chasing the History, Mystery, and Lore of the Persian Carpet (New York, Simon & Schuster), 2005, 38.

[17] Ibid, 64.

[18] Pamuk, Orhan, My Name is Red (New York, Vintage International), 2002, 186.

[19] Ibid, 186-187.

[20] Ibid, 188.

[21] Berger, John, King, 128, quoted in Berger, John, and John Christie, I Send You This Cadmium Red: A Correspondence Between John Berger and John Christie (Barcelona: ACTAR), 2000, unpaginated.

[22] Pamuk, 188.

[23] Bourriaud, Nicolas, Relational Aesthetics (Dijon: Les Presses du Reel), 2002, 110.