I GREW UP during the latter half of the Cold War, when humanity’s survival depended on the concept of mutually assured destruction, and while still young I developed a habit of reading the headlines: Arms Race, Evil Empire, Salt II Treaty Failure. Yikes.

In all of the most foreboding stories, the United States played a determining role. Why did our country have to bear this horrible burden? I started wondering when I was 12 or 13. Where did we get this awful power?

It basically came down to our wealth, was the answer I gleaned from my father and my social studies teacher and Newsweek. And while it might seem like citizens of other democratic countries prospered just fine without the morally problematic ability to kill off all humankind, that was because the United States was paying the bills for freedom. Besides, our lives actually were better than almost anyone else’s in ways not yet visible to my provincial eye—filled with abundance, for one thing, and offering broader choices.

I still had questions, though: How much better, and was the degree of abundance actually worth it? Who said communism and democracy had to be such brutal enemies anyway? In a democracy, couldn’t people vote to collectively own some capital? I decided I’d prefer to live in Canada.

But even as I remained open-minded about socialism, I benefited from being a member of the American middle class. My parents budgeted closely, but as teenager, I got my own phone in my bedroom. I had a stereo. My family purchased a second car, and I often had use of the older one. My friends and I used it to drive to the mall a couple towns over where we bought outfit upon outfit with money earned from our part-time jobs—mostly from the clearance rack, it’s true, but there was always enough left over to get a slice of pizza and a record or two at McCrory’s—albums by Joy Division, New Order, and The Smiths to replace the Air Supply and AC/DC that embarrassed me by the time I had my license. College was a given, and beyond that I dreamed big. I would adventure. I would travel. I would visit the world’s great cities and participate in cultural happenings and party with my favorite bands after seeing them perform.

Much of this came to pass. I’ve had a fortunate time of it. And needless to say, the human race has survived; cockroaches have not yet emerged ascendant. My fear—our fear— of nuclear war is no longer as omnipresent as the Emergency Broadcast System tests that once punctuated after-school reruns of The Brady Bunch. But headlines still make me fretful. Middle-aged now, middle class but feeling squeezed with two kids to raise and educate while my industry contracts, I focus more on the way insurance costs and long-term job prospects are likely to be affected by global warming than on the more dramatically doomsdayish aspects of climate change, but my anxiety levels are similar to when I worried about the literal end of the world, and so are my questions. It doesn’t have to be this way, does it? Then why does it feel so inevitable? And why is the United States so obstinate on points that clearly seem to have no good end?

One recent morning my eye caught on a headline that declared “The American Middle Class is no Longer the World’s Richest.” I felt my stomach clutch. In a way, this news excited me. As a young teen I was eager to trade in our national advantage if it meant a kinder, gentler world, and I always knew that would have to mean a change in American living standards. Part of my dream was coming true! But my yearning to spread some of Americans’ wealth never involved the oligarchs of the world getting ever richer, and as a kid myself I hadn’t thought about how my own children would fare on the long ride down. Would we be OK?

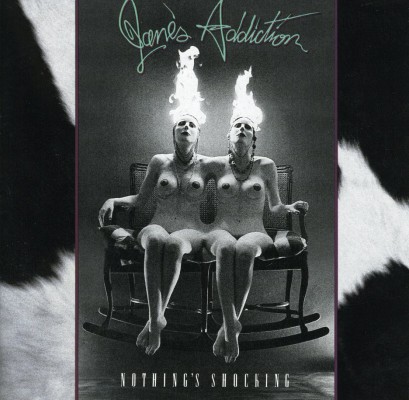

I tried to shake off my anxiety on my walk to work, popping in my earbuds and worked up a stride that nudges my thoughts towards the dreamy and associative. Lately the band I’ve had on heavy rotation is Jane’s Addiction. The copy of Nothing’s Shocking I once owned—cassette, vinyl?—I’ve long since lost, but I downloaded the album this spring after reading an excerpt from Megan Stielstra’s essay collection Once I Was Cool. In it she describes attending the very first Lollapalloza in 1991 and the ecstasy of hearing Jane’s Addiction sing her favorite song, “Summertime Rolls,” to an audience of thousands all sharing the vibe. Oh, live music and youth and times gone by. Listening on my walk transformed my worry about the future to memories of a bygone era, to the years just before the Berlin wall came tumbling down.

I saw Jane’s Addiction in January of 1989 at The Leadmill, a small club in Sheffield, England, where I lived when I was a junior in college. Though I’d dreamed of traveling abroad since I was a pre-teen, believing myself—after having been called pretentious enough times—to have a European sensibility, it was a miserable year for me. I’d gone alone to the region that had given birth to some of my favorite bands expecting to feel an affinity with the left-leaning students thick on the ground there, but instead of being met as a comrade in arms, I found that my American accent immediately put off many of the Brits I met. My flatmates were especially hostile, whispering and snickering when I entered the kitchen. I cooked dinner to this chorus nearly every night, waiting for the water to boil in my one thin aluminum pan. The British pound was strong against the dollar, and I could seldom afford even the cheapest manner of eating out. I was always counting my pence, handing over a few at a time for an onion and aubergine to the man at the vegetable stall. He called me “duck” and “love” and said “ta” to me even after hearing my accent, and I sometimes felt I was paying him as much for that kindness as for the ingredients for my simple pastas.

In terms of seeing live music, however, 1988-89 was perhaps my best year ever. I’d spent most of my life in small towns, but Sheffield was a mid-sized city and Manchester was only about an hour away. Despite the fact that my new acquaintances would not believe I hated racism and Republicans as much as they did and regularly demanded I defend the institution of American slavery and the policies of Ronald Reagan, I managed to fall in with a group of kind people who mostly ignored my nationality, and with them I saw the likes of Billy Bragg, Michelle Shocked, Dinosaur Jr, Mudhoney, Sonic Youth, Nitzer Ebb, The Sundays, Happy Mondays, and, twice, My Bloody Valentine.

But none of these great shows was as sparkling and breathtaking as Jane’s Addiction, who I’d never heard until I saw them in England. From the first bars of their opening song—I don’t remember what it was but I can feel in my bones the rumble rumble rumble before the huge sonic wave—I was aquiver. I grew lighter and brighter, drawn to the stage through the pink-skinned crowd all pushing there too. I made it right to the edge, at the feet of the moonlit owl-on-fire Perry Farrell. He swooped and penetrated and beamed, a lick of spirit, a charismatic preacher inhabited by the light. He was all sirens and spangles and unabashed joy, open as the sea, blindingly AMERICAN even decked in dreads and cords of leather. I left the club exhilarated, proud to share with the band roots in the United States. What a relief to be able to muster some enthusiasm for where I hailed from, since being in Britain had made me realize I was an American whether I wanted to be or not.

The irony is that I might never have heard Jane’s Addiction, not in a way I would have paid attention to, if I hadn’t been in England in the first place. I don’t think their glam sheen would have put them on the play lists of the boys in bands I hung out with at college or the Philadelphia anarcho-grunge crowd where I’d found the boyfriend I was in a long-distance relationship with that year. The people I went to shows with in England were wider-ranging in their taste, less exacting. Although they were music-motivated, I don’t recall any of them having a record collection to speak of. None of them was fact obsessed. None of them were in bands themselves, either, and so our concert-going was not determined by who was opening for whom or any of that kind of reciprocal social weave. Instead, we’d find each other in the campus pub most lunchtimes and look through NME to see who was playing, and if the description sounded interesting and the price was right, we’d meet up later and go.

In retrospect, I suspect the skimpiness of my English friends’ record collections probably had to do with lack of disposable income. The university students I knew in England bought considerably less stuff than the people I knew at home—even second-hand stores like Oxfam were much more expensive and less well stocked than their American counterparts. But live shows were accessible because they were often subsidized. The (very low cost) university picked up most of the tab for concerts put on there. Another venue was part of a theater complex that received government funds. And if I recall correctly, The Leadmill itself had some kind of performing arts grant that helped keep ticket costs low. You could see a band like Jane’s Addiction for just a handful of quid.

Now if the United States could make a trade-off like that—goods costing more but education and cultural experiences less—I wouldn’t mind losing our place at the top of the middle-class heap. Clearly, though, that’s unlikely to happen. Things are going in the opposite direction here, with fewer subsidies for anything but corn syrup and sport stadiums.

I don’t agree with this trend, as must be obvious. But even while admiring Finland’s better paid teachers and more equitable schools, and France’s killer child care policies, and Sweden’s enviable parental leave, and Germany’s vacation allotments; even when hating the guns and the God-fearing and the think-tanked talking points pushing the mantra of individual achievement and personal responsibility in the face of corporate rampage, I don’t ever wish to be Canadian anymore, my hands washed free of American culpability.

As I said: I’m middle-aged now. Why keep pining for what I’ll never have? England was my first taste of this, and traveling through Europe, Southeast Asia, and Central America only confirmed it: no matter how many the moments of international bonhomie, I’m an American in the world whether I like it or not.

So I do what I can to make that less embarrassing. I vote. I pay attention to what’s beyond our borders. I try to get my voice heard. And I’ve come not to mind my American identity, to be even proud. There’s plenty of reason to be, but let’s stick with music.

I was talking to a friend in the industry about how difficult it has gotten for musicians to make a living. He mentioned that many countries were subsidizing promising bands—defraying their tour expenses, helping them record.

“We should do something like that here,” I said urgently, feeling anger mounting already because I knew we would not.

But my friend shrugged. “It doesn’t seem like that kind of support helps creatively, though. If you think about it, almost all of the really original ideas in contemporary music have come from us.”

It surprised me to hear my soft-spoken friend make such a bold and nationalist statement. I scanned my knowledge of rock music history to test his theory. “What about England?” I finally asked.

“Yeah, maybe England,” he ceded. “But, really, the big ones—the Stones, Zeppelin— they’re based on the blues, as American as it gets. So is jazz.”

Decades ago I might have argued with him just for the sport of it, but now I paused and I let the idea sink in. I found something to recognize. Our middle class might be fading. The West we stole might never be won by my political side. But yes, there’s also a rumble rumble glitter bomb of creative energy here, despite or because of our flaws. There’s the pull toward the future as if it need not hold gloom. And maybe it doesn’t.

Happy birthday, America.

i bet that song you heard first by Jane’s Addiction was Coming Down the Mountain

I think you’re right.

Nice nostalgia, Zoe. This piece brought me back to that first Lolla tour in 91, at Waterloo Village, NJ, where i distinctly remember the rush and thrill of dancing to JA in a bikini top and my handmade skirt, and the privilege of being young and free and middle class, actually. American music could not have exploded so forcefully around the world without the mob of hungry, American kids to welcome it with critical mass and their saved allowance. Youth culture and rock and roll were totally symbiotic. One represented the other, and all the great bands knew it, still know it, which is why they always, always thank their fans. After traveling to poorer regions of southern France in my early 20s, and seeing the frustrated youth of a government subsidized culture, I saw how truly different our youth was, how Rock and Roll grew out of the American working class narrative, how that narrative was a privilege as was the dream that you could at least try to do anything, and it would be hard and feel like crap but also awesome, and that people would respect you if you tried. Of course that narrative has since been co-opted, packaged into a business plan and sold as a formula to music consumers–which is what most of us are now since an industry developed around music and youth culture in general. I wonder, like you, about how and if the middle class will ever find a crevice in culture again that is spontaneously artful and expressive, empowering, galvanizing, somehow free of a crushing business model, and that can inspire our kids.

You’re not embarrassed by AC/DC.

AC/DC is embarrassed by you!

You will find pesticides which ennter the entire body through breathing,

by consumption, through intake, and by contamination. The devices may

be safe, but their effectiveness is not established scientifically.

Of course, once they are able to control insect problems such as this,

they will be able to open up for business as usual.