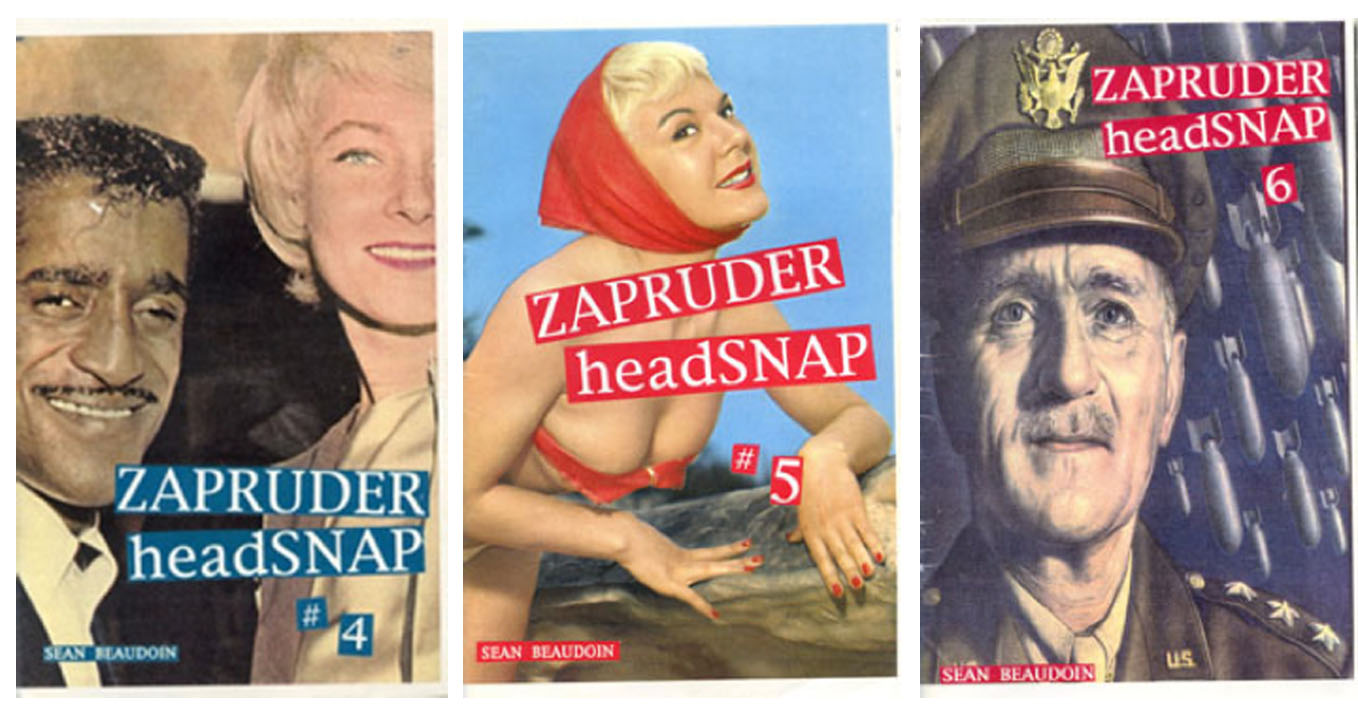

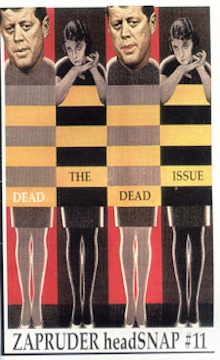

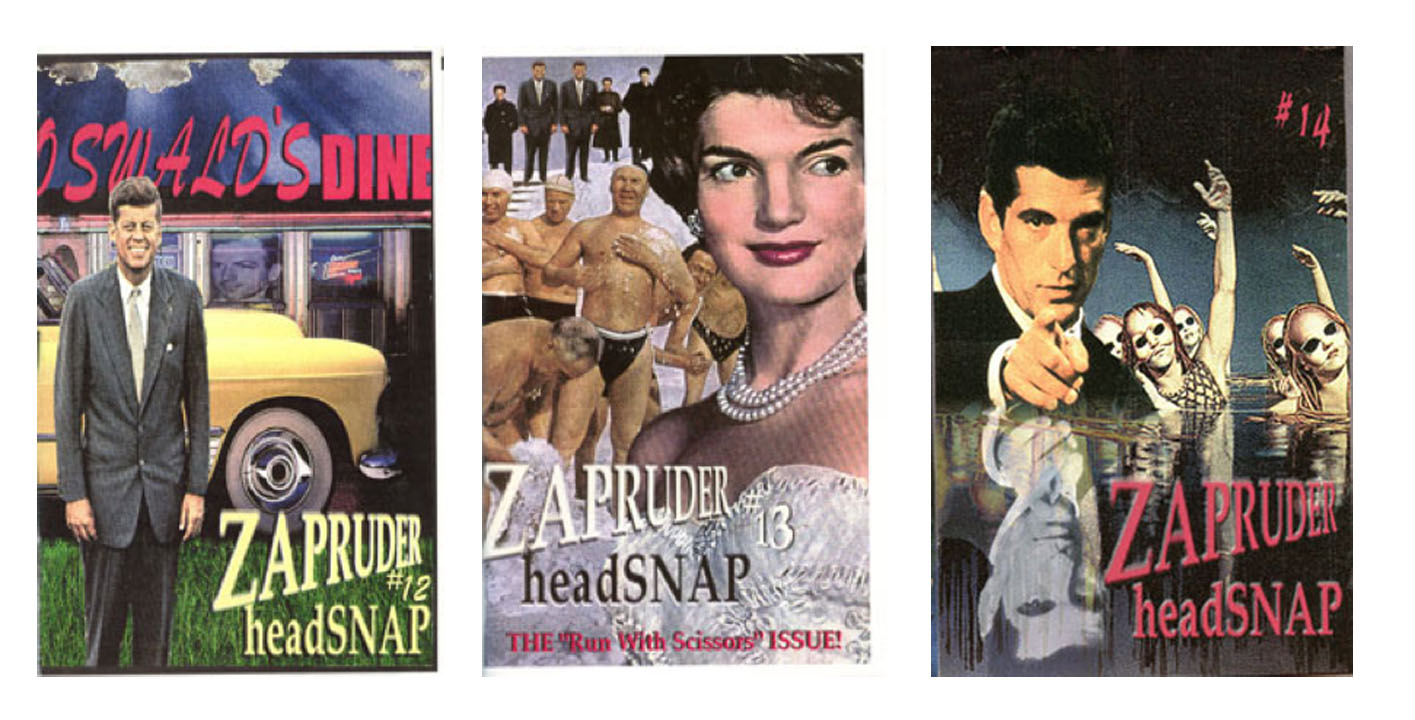

IN THE EARLY NINETIES I published a fanzine called Zapruder headSNAP. Its stated intent was to be politically pointed and baldly satirical, an enemy of political correctness in all its forms. It aspired to be totally original and void of cliche, a broken pool cue with a literary edge busy laying open the scalp of pop culture.

A lot of times, though, it was just plain juvenile. If not outright stupid.

Zapruder headSNAP ran fourteen issues and was actually turning a profit by the final one. Although the word “publish” is misleading, since it really meant “conceive, write, print, glue, collate, fold, and staple every single page in every single issue by hand,” which is the sort of rote hump labor that only the obsessive or indentured would undertake for any reason, at any price.

Back then I clerked at a hotel, abusing the Xerox machine between customers on the overnight shift. It was toxic work. The ancient copier jammed every tenth page, venting clouds of fine black crystals like it had just been lowered into the used droid line outside Uncle Owen’s moisture farm. Fortunately, I’d figured out a way to reverse the page counter with a nail file. The managers were mystified, but my register was always correct to the penny, so they just shrugged and ordered more supplies. At dawn, toner-black from fingertip to elbow, I’d zip back across the city on a chopped Cannondale, twenty pounds of genius crammed into a messenger bag slung around my neck.

I shared an apartment with a rotating cast of aspiring filmmakers and poets and women who wore tube socks on their arms like debutante gloves. Everyone was on the verge of being famous. We almost never spoke. My room was in the attic, up a steep black ladder. Sometimes I’d come home and things would be missing. Nothing too obvious. Albums or loose change. The extra Levis I never wore. Finally, I kicked off the doorknob and screwed eight inches of steel hasp under an enormous padlock. The junkie girl downstairs, who had a pitbull puppy and a boyfriend in culinary school, said “What, don’t you trust me?”

It was almost funny. I almost liked her.

“Trust is a relative concept,” I said. “Also, the Timex my father gave me for my sixteenth birthday is sitting on your dresser.”

With the door finally secured and The Stooges cranked, I’d strip down to my boxers and spread freshly-printed pages across the floor like a losing hand of canasta. Columns, covers, centerfolds. One crease, one staple, one sticker at a time. Iggy grumbling his way through 1972. A Helvetica of smut. Car alarms, spilled bourbon, and gusts of fog that swept past my window like someone was burning tires.

Slowly, the issues came together.

Once a month I shouldered stacks of finished zines and peddled around San Francisco, refilling orders. I had consignment deals at every hipster spot in town: Naked Eye, City Lights, Leather Tongue, Maximum Rock N’ Roll, Amoeba, and Bound Together. The debut issue of Zapruder headSNAP probably sold forty copies. By the time I shut it down a few years later, primarily out of boredom (and the encroaching Internet), Tower Records was distributing Zapruder headSNAP in New York, Chicago, and LA while I cranked out runs of a thousand or more.

It seems like such an innocent time now. There weren’t any cell phones. Most of the people I knew had barely begun investigating chat rooms. I stubbornly refused to load in a Netscape mailer and try out my first dial-up connection, under the impression that ignoring the Internet was some sort of political statement. Besides, after the first few Zapruders came out I started to get a ton of letters, actual mail, envelopes filling a technical void in a way that seemed both anachronistic and cutting edge.

My PO box was in the heart of the Tenderloin, a tiny storefront in which a seedy, attenuated British gentleman had installed file cabinets, a sofa, and his ancient mother. There were forgotten packages and manila envelopes spread randomly across the floor, but he always knew where my stash was, good for a wink and a ‘allo Guv’ner like he’d just been released from Bleak House.

Sometimes I got too much mail to bike home in a single trip, a burlap sack of envelopes, each madly addressed. They contained love letters, hate letters, other zines, orders for back copies, three dollar checks, six dollar checks, cash, bizarre religious tracts, conspiracy rants, short stories, long stories, drawings, fetish dolls, prisoner requests, rancid poetry, mediocre poetry, arguably competent poetry, and many beaver shots. It’s bizarre (and says something profound about our society, although I have no idea what) how many nude pictures I received. Not digital. Not arty. Not attractive. Polaroids and Instamatic prints. Kitchen shots, poorly-lit. Masked women, crouched. Swinger couples wearing a snood and a fez. Muscle guys with rashes and scars. Pale girls looking out the windows of shabby apartments like album covers for bands that were too depressing to exist. Once, I received a Ziploc baggie full of fingernails. Full. Bulging. Like most things in life, it was both repulsive and impressive, a low-rent taste of Damien Hirst, a post-modern comment on blind but misguided enthusiasm.

Which is precisely the sort of effort required to put out a fanzine.

Most people, though, wrote long letters. Incredibly detailed and sincere and almost uniformly lonely. About articles they liked, articles they hated, their politics, their relationships, their reading habits, good ways to masturbate, bad ways to masturbate, their lousy jobs. The collective need to simultaneously connect and unburden was overwhelming. And more than a little terrifying. The need to threaten wasn’t entirely rare, either. Still, I loved those letters. I loved being someone who random anonymous people wanted to write randomly and anonymously to, perhaps recognizing in my sentences a kinship of existential fear and confusion.

The name Zapruder headSNAP presented itself during a brainstorming session at the 500 Club, over Miller High Life(s), with my original partner Roland. We had a long list of potential titles:

The Voight-Kampff Test

Bop City

Redrum

Actually, Alice Does Still Live Here

Ouroboros

The Port Huron Abatement

Your Corporate Rag

and

Yeah, But Could Warhol Actually Paint?

All of which sucked.

“Well, what’s something you really care about?” he prompted. “Music? Art? Politics? I mean, essentially, what we need here is a theme.”

He was right, but those things all seemed overly broad, and done already, better and worse, everywhere.

“Well, I have been thinking a lot lately about the Kennedy assassination.”

He laughed. “What about it?”

I cleared my throat and attempted the rare trick of breaking through a lifetime’s entitlement and entropy in order to explain what felt like a nuanced–but in truth not overly examined–concept to another human being. “Well, you know, just that there’s this narrative we’ve all swallowed, right? The genius of Jack. The visionary. The Kremlin nut-buster. But from Camelot to the Pillbox Hat to the Bay of Pigs, it was just a cheap con. We so badly wanted to believe we were capable of something pure, something better, that we all blinked like that kid in The Twilight Zone who transports the adults out into the cornfield when he doesn’t get his pudding fast enough.”

Roland thought about it, wary I was about to get on a serious tangent. “Yeah, I ah…I guess I see what you mean.”

“But, you know,” I said, too late, “it doesn’t really matter if the myth was true or not. What matters is that when it ended, it was the last chance this country had of ever being progressive, or run by anything but a train of zealots and bankers and shills for white evangelism. I mean, the rot started right there, the second those shots were fired. Innocence, violence, the collapse of post-war idealism. Vietnam. Hippies became hustlers. Pot became hard drugs. Hope became nihilism, the last holdouts riding McGovern’s stillborn wave, before the dark cloak of Nixon finally–”

Roland slammed down his empty. “I like that! How about we call it The Dark Cloak of Nixon?”

I shook my head, exasperated. “Listen, dude, my point is, like that Bradbury story about stepping on the butterfly, how would things be different, right now, without Oswald? I mean, Abe Zapruder, who is like the epitome of totally random, was there to get the footage. And that head snap is the most transformative nine seconds in our nation’s history. That’s what our magazine should be about.”

“Interesting,” he said, in a way I could tell he didn’t think was the least bit interesting, but then the bartender plopped down a fresh round and it was easier to lap it up than wrestle over the idea anymore, let alone a better name.

In the end, Roland lasted about as long as the hangover. Not even through the first issue. He dropped out when he realized manually conceiving, writing, producing, and distributing a zine is, in fact, a shit-ton of work. After that, I decided to do it alone. I didn’t feel like depending on anyone else, cajoling or hectoring them about deadlines. I am both terminally obsessive and a classic insomniac, so it was easier to just flog myself through the night. I wrote long investigative pieces about Scientology and the conspiracy of ISBN numbers. I wrote articles using the bylines of the Kennedy assassination’s bit players, like Clay Shaw, Ferenc Nagy, Orville O. Nix, Officer J.D. Tippet, and Marina Oswald. I reprinted Family Circus cartoons with new text, revealing its subversive intent. It’s amazing how demented the Family Circus is when you give voice to what those children really want to say. But Zapruder headSNAP was mostly comprised of cultural rants: railing against Grunge and knit caps (their sudden ubiquitous-ness), against tattoos and nose rings (the utterly false rebellion they represented), against religion (its corrosive anti-intellectualism and ludicrous origin stories), against hypocrisy (everything, everywhere), against consumerism (manufactured meaning, the fallacy of ownership), and against myself (oh lord, where to start.) I wrote about my life, my job(s), friends, girlfriends. My desire for a voice, for a creative community, for a new literary salon, for a purpose.

I think.

I can’t bear to go back and read any of it. I have no clue who the person was who wrote all that shit. Or even why. Possibly sublimated anger that I hadn’t already been handed a staff position at Vanity Fair on the strength of the observances I jotted on napkins in cafés? Or that one of the Coppolas hadn’t somehow seen that funny video I made in college and offered me a slot directing Rumble Fish II? Either way, I was mired in a minimum wage job, a shitty relationship, and the waning collegiate notion of being “an artist” suddenly rendered laughable in the face of rent. I guess I thought I was owed something. And that people who liked Limp Bizkit were going to pay.

At that time, I hung out a lot with my friend Ely. He was the kind of guy you could hand a wig and a dress on a busy street corner and suggest he do rude things in the name of art. As long as a camera was rolling, Ely had no fear. Or at least he had an enormous fear of being boring. Of not being regularly involved with the sort of inscrutably meta street performances that would enable your average retail shlub to skewer all of society’s bullshit with a quick skit involving a dildo and a cowboy boot. We did lots of those skits. Ely appeared in most of Zapruder headSNAP’s issues in various disguises and as numerous characters. He wore make up, thongs, mini skirts, pig masks, neck-belts, false limbs, trucker hats, and condiments.

He was less-funny Borat to my less-talented Mamet.

Once we drove down to the Alternative Press Expo held in San Jose. I’d paid for half a dealer’s table, intending to sell shirts and zines. He thought that sounding a little tame, so we stopped at a thrift store for a moldering terrycloth bathrobe, slippers, and one of those metal geriatric walkers that have two wheels and tennis balls impaled on the front posts. At the diner across the street, he put six packets of apple jelly in his hair and rubbed coffee grounds under his eyes. In the expo hall he slipped into the bathrobe and taped a file folder with a bunch of zines to the front of the walker, along with a sign that said: Flesh Is A Disease, and I Have It Bad. Please Help! Buy One Copy. Then he shuffled through the packed crowd.

The organizers kicked us out in about twenty minutes. And not nicely. The guy running the thing was this big Soprano dude, and he was pissed.

“Are you responsible for this…person?” he asked.

“Um, sort of.”

“Then you got to go.”

“Why?”

“People have complained. They’re getting upset.”

“About what?”

“You know what.”

“But isn’t this an alternative press expo?” I asked.

“Yeah, so?”

“Look around.”

He did not look around.

“Shit, man, there’s table after table of people selling books on bomb-making and Pol Pot and how to cook meth in your bathtub.”

The guy seemed uncomfortable, but also like he wanted to punch me.

“That prick over there is selling The Protocols of The Elders of Zion. That might be the most evil book ever written. You’re telling me he can stay, but you’re kicking us out?”

“Yeah, that’s what I’m telling you.”

Clearly, it was pointless to argue. And, also, he was much bigger than me. But somehow we’d crossed an imaginary line. On an inexplicable level, sickness was worse than the most indefensible political or social stance. On the other hand, I felt a certain amount of pride. Crossing the line did seem to be the ultimate point of Zapruder headSNAP. If there was a point. I can’t remember anymore.

“Can I at least get my entrance fee back?”

“Get the fuck out of here.”

At a rest stop up the highway, Ely washed the jelly out of his hair, and then we went to a matinee of Alphaville.

In retrospect, it’s amazing how incredibly vibrant and popular the zine culture was for a few years there. It was a solid component of the national underground vibe, and countless titles came and went, some for a single issue, others gathering a real following. It was part of the punk/DIY aesthetic, but also anarcho-neutral in the sense that there were no rules, no mandated subjects, nothing off limits. Mike Diana made national news facing obscenity charges for his (purposely?) horrible drawings. Pete the Dishwasher went on Letterman and pulled a pretty good prank. Other zines developed huge audiences and snagged book deals. In a way it was sort of like the pre-Internet. A practice run. Paper blogs. And, like blogs, there were many zines that were pointless or offensive or simply mediocre. But there were also pockets of true brilliance and creativity. Zines would regularly arrive in the mail and absolutely blow me away with how hilarious or ingenious or beautiful they were. And then I’d never hear of them again. It was a tiny little universe that seemed genuinely without constraints. And then, suddenly, like every other underground movement–from breakdancing to tagging to raves–there were exposes in the NY Times and Rolling Stone, and the death knell of wider acceptance tolled. Not long after zines were acknowledged as a “form,” most of the culture built around them disappeared.

Which is just as well, since VoyeurDorm.com, offering 24 hours of totally amateur chat-cam content, was waiting to pounce.

But in the end, the reason I decided to hunker down and write this mini-history, was a pair of Google alerts I recently received.

The first features Zapruder headSNAP in an unheard-of mint condition complete set, being offered in a rare book store for only $950.00 (scroll down a bit.)

The second appears to be the archives of a woman named Laura Jacobson, a writer and documentary filmmaker, who had seven copies of Zapruder headSNAP filed in her research papers when she died, donating them to The Fales Library Trust in Manhattan. It seems such a strange thing that she would have held on to these issues, that they were part of what she considered her materials, that maybe they actually meant something to her. Or, maybe she meant to toss them and just never got around to it. Either way, I found their inclusion in the “Downtown Book Collection” to be touching and poignant. Which, you know, was not a feeling otherwise much associated with the magazine itself.

So it prompted me to record what was.

Ignore me here: The Face Book

Disdain me here: The Twitter

Join the vast line of people not visiting my site here: seanbeaudoin.com

Brother Ely! The other thing I remember best is that the Zap acted as a herald straight trumpeting what I imagined you’d say right to my face, living in semi-squalid dilettantism in New Orleans. Sometimes I’d yell, “Harry Connick Sr. made a mint off of JFK’s death,” up at the clouds, proud to know you’d be able to hear me way up yonder in your Tenderloin mail stop. The thing was, I had an old lady that at times I tried to please. Holding up your zine made me somehow less antiquated, but more anachronistic- that is, with the Zap I became strangely more appealing because I knew people who did strange and weird things with their time. Zapruder was our dove. And now it’s gone, and she and I are divorced- you’re to thank! And believe me, I’m thanking you.

You got it, baby. It always heartened me to know people were laying in the dark on dilettante futons everywhere, appreciating the weird and the rude. At least as I could provide a glimpse of.

I new he waz great writer. Plus, when my room mates used up my half-n-half he would skewer them, using their real names in a barely fake, extremely unflattering story.

Wow, neat. I was also a mid-90s ‘zine guy. I put out about 35 issues of GoodBye! – the Journal of Contemporary Obituaries (www.goodbyemag.com). I don’t think my life was ever as punkish or desperate as yours, but it was pretty weird, living in an urban backwater that would eventually become one of the most upscale neighborhoods in the country, Carroll Gardens, Brooklyn. When I was there you had to watch out about walking near the projects or you could get punched out by roaming gangs, as I did.

But my little obituary magazine, 12-16 pages per iss, got reasonably popular – a couple hundred subscribers. I don’t really know how this happened because I did little to publicize it. But nobody ever sent me a bag of fingernail clippings.

I had a decent job at a Wall Street bank at the time so I didn’t need to steal printing services. I lost money on every issue despite my announced $10 or $15 annual rate. But I didn’t give a shit. One of my proudest moments was sending out a resub postcard with the classic National Lampoon picture of a dog with a gun to its head under the slogan, Buy this magazine AND we’ll kill this dog! “Deaths of the Animals” was a popular regular feature in GoodBye!

Like you I was loath to deal with the Internet. But in the late 90s I put everything online and was shocked to get profiled in magazines and websites internationally. This weirdo from Brooklyn who writes funny obits. The web was cute in those days.

The Wall Street bank job turned bad when Osama Bin Ladin et al crashed a plane into my office building. I ran down 78 floors and survived. By then my printer had been imprisoned for taking out a contract on his wife’s life. I kept going, but then what nailed the coffin for GoodBye! was that I was forced to go legit.

The Wall St. job actually didn’t stop with the 9/11 attacks. We built a new office in midtown NYC. But in 2002 I got laid off and sent some clips to a fledgling daily paper, The New York Sun. The editor called me up for a job interview at the very moment my wife went into labor with our son. I begged off but a few weeks later I was hired as the paper’s obituary editor. The Sun eventually folded but I’m still a newspaper obit writer and my son is a happy 10-year-old.

A couple months ago I was asked to do a reading at a fundraiser and went over some old issues of GoodBye! I was just learning to write. Some of it is hilarious, some sophomoric. Some better than I could do today. It’s really fun to admire your former self. Maybe it gets aggravating when you get older.

This is a great little history, Steve. Thanks for providing it. I’m gonna check your Obit action out.

I enjoyed this very much. I knew Henry Cherry from some school in Ohio and he put me onto your words. I used to read F5 and not send away for many zines, and when I did they had just stopped publishing. But I did spend time in Chicago’s Quimbys and still have some Answer Me!s and issues of Apology around here somewhere. If you scanned ’em up and posted them I would probably read every word and then hand $10 to our local couch-surfing eccentric, former Warren horror comic writer T-Casey Brennan, in your honor.

Thanks for the history! I was remembering my adventures as a young artist in San Francisco in the 1990s, and your ‘zine popped into my mind. Would Zapruder Headsnap even be remembered, or reflected on the web. I can recall seeing the ‘zine every time I went to Leather Tongue video on Valencia Street, when I was sharing a flat with other artists at 19th and Folsom. I rented vhs tapes there often, and was always so impressed with the ‘zine’s title alone. As you say, the content was pretty juvenile, but I was impressed with the effort that went into the endeavor, and I totally understood the need for an outlet, and a community. I miss those days of ‘zines and analog communication immensely. It will never be the same in virtual culture, no matter how many advantages technology offers. Thanks again for telling your story.