GAUZY COTTON SHEETS wave across the ceiling of a former Masonic temple. They veil the lights and a wooden grille overhead with slats in the shape of stars. I stare up and get stuck on the word “like,” not whether I like the installation and how it reconfigures the room (I do immensely) but the idea of likening itself. What if you stop and cut off the analogy you’re about to make and leave it open? I was going to try to describe the fabric in terms of something familiar and recognizable, which would help you picture the room. But what if I stop there, rather than completing the image the words connect to? What if they’re not like anything? What any analogy exposes is not the exact thing itself but its failure, that it’s not this thing. Hold back and there’s a gap, the space the simile was going to paste over. Let the hole remain and you expose something more profound, certainly more unfinished and shaggy than the thing you were going to compare it to in the first place.

This is what happens in Kate Newby’s work where the changes she makes in her installations are slight, some stained fabric billowing overhead, a curtain hung to create a corridor in a gallery, or a bit of concrete put in an awkward spot, and she uses them to make us aware of small, subtle things. So, as I rush to turn her work into gleeful associations because I love the sheets and the way they billow, the words I write in my notebook are “clouds, sky, weather….” The fabric “laps down in waves,” yes, “waves” on the altar. But her installation is not any of this, and my associations obscure its possibilities. The fabric hangs a third of way down from the ceiling, shrouding it while also making you more aware of it. Temples, like churches, by their very nature are hierarchical, directing attention to the front, to the altar, but she interrupts that order. She makes you look up. Then, there are the sheets themselves, a puzzle too, with footprints and rain-stained striations from where they’ve hung for a month outside as she worked. Now they’re a quasi-chronicle of her time in a studio on the roof of a Masonic lodge. And, there’s the concrete blob forcing the temple doors open.

For her installation Maybe I won’t go to sleep at all last autumn in Brussels at La Loge, these ghostly interventions spread across the building let you see it anew. Why ruin that by making her work like something else? It asks you to pause on the tiny gaps, the word like maybe.

Sheets as, as, what? Stains, covering, clouds… Kate Newby’s “Maybe I won’t go to sleep at all.” 2013, installation view: La Loge, Brussels, all images courtesy of the artist and Hopkinson Mossman, Auckland.

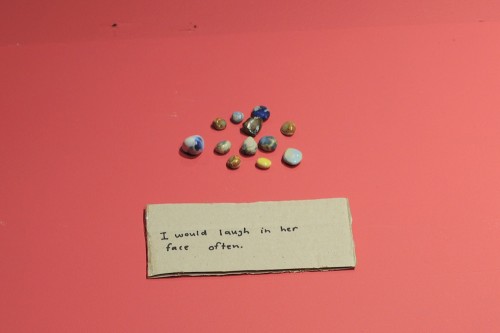

A Masonic lodge turned art space, La Loge comes loaded with those associations of secret societies and the pyramid and all-seeing-eye on the US dollar bill that always accompany Masons. Newby’s installation subtly interrupts that. She starts in the basement with her groupings of rocks on a low plywood platform in the middle of the room. Before each set is a tag, not quite a caption, to the pieces. Labeled “Shelter Island,” or “Depend upon it,” or “Do more with your feelings,” they could be commands or places or something else entirely.

Maybe I won’t go to sleep at all., 2013, installation view: La Loge, Brussels

On the next floor is the temple and above that a corridor she’s covered in the same cheap carpet landlords hope will hide stains. On it she writes in chalk, “oh hi.” The dot on the “i” is rubbing off where people have walked on it. On the top floor a clay wind chime hangs knotted to the outside of the building. It’s as if she’s moving from bedrock and foundation to air and wind, but that as if also elides the strangeness in the pieces, the way the tags don’t fit the stones, the way the string on the chimes is threaded through rough holes gouged into the walls, letting in light. She attacks the building but not like other artists might; this is no grand gesture. Meanwhile, some of her rocks look “real,” others handmade and rough, bearing the scars of their making, the glaze imperfect. At the window is a collection of nails and coins and pull-tabs from cans. They’re “pocket charms” she calls them that she’s carried around with her for months, and they’re laid out on both sides of the glass. Some she’s found on the street, others remade and cast in silver. It’s not important to know what’s “real” and been collected or what’s “art” in being remade. Instead it’s the question, that gap of not knowing.

Maybe I won’t go to sleep at all., 2013, installation view: La Loge, Brussels

Just to enter the temple you’re forced to step onto a blob of concrete that shoves open the doors. Obscuring the Masonic symbol, the blob is a question too. Is it blocking the entrance? Do you walk on it? How do you know what to do? Are you allowed in? Then, how do you interact with something defined as art? The question is subtle. This isn’t institutional critique, nothing that heavy. The answer is left to the viewer, but the question itself is the same gap left open if you pause to consider the small situations and interruptions in Newby’s work. At its heart she’s asking us to reconsider the world around us. She’s offering us an attunement to it.

Maybe I won’t go to sleep at all., 2013, installation view: La Loge, Brussels

~

In 2012 she won New Zealand’s biennial Walters Prize, and up until about five years before she didn’t even show in galleries. She refused to. Instead she’d choose ad-hoc spaces like the path students used as a shortcut to the university in Auckland. There on a hilltop she put up a flagpole. There was also work in abandoned buildings and friends’ flats,[1] and this fall in Copenhagen for part of a show at Henningsen Gallery she installed a set of wind chimes atop the city’s highest hill. Only there was no sign for the chimes, no didactic text or directions at the gallery, nothing marking this out as art. To see them you’d have to stumble on them, and she’s said she likes work that’s a bit “renegade,” that “you encounter if you are walking or you might hear from a distance.”

Last winter on Fogo Island off the Newfoundland coast, she made a pothole. (Her work is full of literal gaps and holes like this often celebrating puddles and scabs in pavements, and the small ways they transform the world). Getting to Fogo Island takes at least two planes and a ferry, and her piece was remoter still, at the end of a dead-end drive by the sea. Meant to fill with snow, melt, cover with ice, get driven over and eventually disappear like an actual puddle, her puddle required burning a fire over the spot for a day just to thaw the earth to dig the hole. The piece was almost an earth-work in miniature, except only a few people ever knew of its existence.

Not the puddle on Fogo Island but Newby’s “Walks with men,” 2011

mortar, glazed ceramic rock, bronze, silver pebbles.

installation view: Prospect: New Zealand Art Now, City Gallery, Wellington

photo: Kate Whitley

For several years she’s made a series Let the other thing in of rocks to skip in water. It’s possibly a performance, but maybe not. Maybe that’s too defined a word for it. Kate hands a porcelain pebble to friends to skip across everything from swimming pools on Long Island to remote ponds on Fogo Island, the East River and the Mississippi, wherever she and a friend happen to be. She’ll slip you the stone, and I can tell you the moment is difficult, exhilarating and an honor. You’re being given something she’s made and asked to chuck it away. But what is it exactly? What transpires? Is the moment art? Is it the pebble she, the artist, makes, or is it the friendship being celebrated, or the act of skimming the stone? Or, that you throw away something she’s made and it disappears forever? Or, the photo documenting it on her iPhone? No matter the answer, something ephemeral is being marked and that becomes a way to consider all those questions.

Let the other thing in (Drew), 2013, c-type print. Courtesy: the artist and Hopkinson Mossman, Auckland

When Newby handed one to Anne-Claire Schmitz who curated the Brussels show, she protested that she couldn’t, that she didn’t know how to skip a stone. She was also scared of throwing it away and wasting it. Newby told her it didn’t matter, and Schmitz skipped it, the one time she’s succeeded in bouncing a pebble off the water’s surface. Afterwards she said the loss was worth it because she did it right. Her success made the sacrifice okay, a comment I love because it adds to the levels of interpretation with the series. When I tried, mine skidded on the ice stopping in the middle of a frozen pond. Maybe the rock got covered with snow later, or maybe it’s at the bottom. Maybe it’s been picked up by a bird and carried off. The project, though, was originally meant to exist entirely outside of galleries because as Newby puts it, she doesn’t “want to wait for a nod from the art world saying it’s okay to make art now.”

In her gallery installations you get the sense that she’s trying to escape the gallery itself. Just the title alone of her show at Gesellschaft für Aktuelle Kunst in Bremen hints at what she’s up to: “Crawl out your window.” Nominated for the Walters Prize for her installation there, Newby created a corridor with a curtain shaping the light from the window and drawing attention out of the gallery. If you looked across the river you’d see two hand-scrawled words on a wall: “Try, Try.” They were in response to a Lawrence Weiner piece on GAK’s riverside foundations. In perfectly kerned letters he’d written, “HAVING BEEN BUILT ON SAND WITH ANOTHER BASE (BASIS) IN FACT” about the sinking of culture and GAK itself and the island on which the gallery stands. Her piece and its exhortation were filled with hope and humor. Try, try…. She knows it will fail. Her graffiti will inevitably be erased or covered up or wear off, and people won’t get it or will miss it entirely, but it’s about the encouragement to see, to respond, about the hope offered up in the tiny revelations available to us if we look, if we are open.

When awarding her the Walters Prize Mami Kataoka, the head juror, called Newby’s work the “least eloquent” of the four nominees.[2] Her own art dealer has called it “indifferent,” speaking of the skim stones,[3] and Kataoka went on to describe Newby’s installation as “the most reserved but radical way of transcending the fixed architectural space for contemporary art.” Newby’s word for all this is “casual,” meaning unfixed and responsive, reacting to the situation where the work exists, and she gets frustrated when people fill up the spaces, be it in a gallery or, say, that gap left by an incomplete analogy. She writes in notes for her thesis about an artist who altered his gallery’s space and lighting to create a new awareness of it. Then, he filled it up with his sculptures. Why so much stuff, she asks. “Why do people always have to put their work into things? Why can’t it just be a thing? Not like a performance but more like a situation. A situation with less stuff.”

Maybe I won’t go to sleep at all., 2013, installation view: La Loge, Brussels

Instead, she wants to underline how you see the space itself. For a show at Hopkinson Cundy in New Zealand in 2011 she fell in love with a line of nails in the floor and remade it with shinier, newer ones, shaping the light so people would hopefully notice them. On the top floor at La Loge, the flag outside is an invitation to look beyond, to see the sky and sun, and the white sheet flaps there emblazoned, “I think I’m doing it in a really interesting way.”

Her work shows the possibility in noticing the small failures and fissures and approximations of the world around us. Like she did on her flag, she reuses scraps of language and inspirational slogans found on packaging and juice bottles. She’ll also write odes to a carrier bag caught in a tree, and the patches and scars on a stretch of sidewalk transfix her: “The debris, bits of rubbish, sticks, gum and concrete impressions left on pavements are very special things. They are markers of time spent and people living.” Meanwhile, she’s been photographing the bag for days, “having the time of its life out there. Blowing about being cheeky, somehow flying past the rules and regulations of the city and the things around it. Not a bad idea or model for art in the world. Why stop short?”

Why indeed? There’s such a joy in the world in her observations, and as she recreates these elements in her work, the banal becomes transcendent, only it’s not necessarily pretty or graceful. It can look awkward and disarming. It’s a blob on the ground, a handmade puddle gouged into a ramp she’s made in gallery like she did at the Auckland Art Gallery for her Walters Prize show. Or, stained cotton strung across a ceiling. They make you stop because they’re not “like” what they’re supposed to be, because they’re weird and out of place or vaguely familiar but not quite enough.

Newby sees the everyday as an emotional terrain inseparable from what she makes. It’s there in her rocks and pocket charms and the sheets in the Masonic temple. Because she develops her work in response to an actual space, what she shows is her emotional engagement with it over time, inserting herself and her daily, lived experience into temples, galleries, museums…. I’m tempted to call her work feminist, only Newby herself makes no grand claims and refuses to ascribe to larger theories or critiques. Her work is intensely small and personal. How do you write about a woman who makes work from the residue of emotions without that sounding like a trap? Yet she uses these to transfigure the spaces where she shows, and she doesn’t ask for a perfect understanding or you to untangle her feelings or for them to be made manifest.

Back in the temple, I stand under the canopy, the _________. I stop, stuck again on the word “like.” Similes, they’re cheap and easy – and the art writer’s stock in trade. Her work is full of holes and approximations, which if you pause on them provide new openings. So, instead I want to stop on the act of approximation and leave that hole open a bit longer. In notes for her thesis, she writes of a friend using a word in a slightly off way. He was describing a fight with his boyfriend as “really heavy scenery” versus “a heavy scene.” That small mistranslation delighted her. She calls it “jolting and brilliant…. It’s fitting, but not correct. It’s saying something but in a fresh and unusual way. It’s that little bit of a tweak, that little twist, that perhaps all things need, art and otherwise.” It opens up that moment so you see it anew, and that’s really a way of describing her work – jolting, awkward, slightly off and maybe a bit embarrassing. She’s said she knows a piece works if she’s embarrassed by it. What she makes is “really heavy scenery,” where you pause on the approximation that never quite fits. Her work allows the image you (or I in this case) would use to describe her to fail.

To be an art writer and have your words ripped out from under you, to experience – as I did in that temple – the very failure of language, is incredibly profound. It felt like a philosophical proposition, as if Newby hasn’t just reconfigured the space, but the very way I see the world and the way we try to normalize it by the pasting over the bits that don’t fit, by making them understandable, by making them seem like something else. Instead the gaps and trash, patches and emotions, the shonky everyday that she celebrates seems full of limitless possibility.

you manage to articulate the shonky fact that she can’t be articulated. also, I just had to use that work. shonky.

Shonky I know. One of the best bits of Brit-idioms to be had. And to articulate the unarticulate-able… which itself has a much better phrasing too. Many thanks Ms J.