Over the next month we’re excerpting Tessa Laird’s social history of the spectrum A Rainbow Reader. Last week in Part III she wrote of yellow, the color of Van Gogh and desert raves.

IS GREEN THE color of love, or just the color of my love?

Green is the color of the heart chakra, Anahatha, which is Sanskrit for unstruck, like a gong or drum which sounds without force, resonating with its own, intrinsic sound. In Tantric thought this unstruck sound is only heard by the yogi whose senses are withdrawn from the external and turned inward.[1] Green is not attention-seeking.

How strange the Hindu ancients chose green for the heart, that pulsing blood-pumping machine. In the West, hearts are always red, associated with roses and lipsticked mouths, the candified prettiness of St. Valentine’s Day, or the flaming tortured heart of Jesus, dripping blood. But never green – that would suggest green blood pulses in our veins, like Star Trek’s Mr. Spock – that we are thin-blooded creatures of logic, not passion.

Green, though, is the heart of the spectrum if we start in red and end in violet. In the Mayan directional system, red was East, white was North, black was West, and yellow was South, but the center was green, or more specifically yax, which could mean blue or green; blue-green, like our planet, at the epicenter of reality.[2]

Green is at the center of my system, not just because, as Terence McKenna warned, we need to “Go green or die!” but because my love loves green. I mean, really loves green. Green is the only color he will abide, though he makes room for the occasional contrasts of orange or yellow. “Just as long as it’s citrus,” he says. I have never come across this kind of relationship to color before. I know many color-lovers, but none so dedicated to a single hue. Like green itself, what McKenna calls “solid state” energy, my love will not budge on this (or on much else).

~

It’s hard work being tied to someone. Linda Montano should know – the performance artist was tied to Tehching Hsieh for a whole year, by an 8-foot piece of rope. They did everything together, but never touched. The performance began on July 4, 1983 and ended on July 4, 1984. I guess they chose Independence Day for a reason.

An ex-nun and self-professed spiritual athlete, Montano got high on self-denial. Hsieh was an art monk who lived inside a cell for a year. He lived on the streets for a year. He tied himself to Montano for a year. And he punched a clock hourly for a year (One Year Performance, 1980-81), shooting one frame of film each time he did so. In order to enhance the stop-motion passage of time, Hsieh started the year with a shaved head, and ended up with shoulder-length black hair. He wore a working-man’s boiler suit, and though I’m sure he intended to look at the camera blankly, at moments in this filmic record there seems a baleful hatred in his dark eyes, hatred for the one-eyed beast of a camera to which he has enslaved himself, hatred toward the whole capitalist system of production he is parodying. In Ghost of Chance, William Burroughs writes, “Man was born in time. He lives and dies in time. Wherever he goes, he takes time with him and imposes time.”[3] It was his greenest book, in which he mourns the loss of biodiversity in Madagascar, and of the lemur in particular, whose very name means ‘ghost.’

Linda Montana and tied together for a year.

Montano said at the end of the ‘rope piece,’ “Tehching is my friend, confidant, lover, son, opponent, husband, brother, playmate, sparring partner, mother, father, etc. The list goes on and on. There isn’t one word or one archetype that fits.”[4] This is what Hsieh’s time-clock film becomes, a fluttering, stuttering portrait – as if he was being electrocuted – of many people, though all of them are angry, greenish-tinted Asian men, black hair whipping about their faces as they stubbornly glare down Father Time. Apparently, Ancient Egyptians called time “the everlasting green one.” [5] And I think of my own man who loves green and his stubbornness and the invisible rope that ties us together. Hsieh, familiar with debilitating restriction, said of the rope performance, “We become each other’s cage.”[6] Meanwhile Montano said that thanks to the performance she was “much more comfortable with the negative.”[7] I understand and agree, but then, Montano’s performance only lasted a year.

Though stubborn Tehching talks in absolutes: “When we die it ends. Until then we are all tied up.”[8]

~

Van Gogh characterized the song of cicadas as green: “The cicadas are singing fit to burst (…) here they still sing in ancient green.”[9] In the proto-environmental memoir Walden: Or Life in the Woods, Henry David Thoreau sees the leaf as the ancient, green, universal pattern of all things: “You find thus in the very sands an anticipation of the vegetable leaf. No wonder that the earth expresses itself outwardly in leaves, it so labors with the idea inwardly.”[10] To Thoreau, feathers are simply drier, thinner leaves; butterflies’ wings are leaves. “Even,” he wrote, “ice begins with delicate crystal leaves, as if it had flowed into molds which the fronds of water-plants have impressed on the watery mirror. The whole tree itself is but one leaf, and rivers are still vaster leaves whose pulp is intervening earth, and towns and cities are the ova of insects in their axils.”[11]

Thoreau extols the eternal green of grass, which “flames up on the hillsides like a spring fire, as if the earth sent forth an inward heat to greet the returning sun; not yellow but green is the color of its flame;—the symbol of perpetual youth, the grass-blade, like a long green ribbon, streams from the sod into the summer, checked indeed by the frost, but anon pushing on again, lifting its spear of last year’s hay with the fresh life below. (…) So our human life but dies down to its root, and still puts forth its green blade to eternity.”[12] For both Van Gogh and Thoreau, green is ancient, everlasting, eternal.

~

My green-loving love became even more green as a teen, the day his beloved dog died, promising to never again eat something that could understand tenderness (as can dogs, cats, birds, rabbits, cows, pigs, sheep, goats, chickens, horses, and definitely dolphins). In her essay “Edible Matter,” Jane Bennett argued for the agency of food, its capacity to effect change in its consumer, but not always in the way we might assume. A similar thought once occurred to Thoreau in Walden’s woods. Glimpsing a woodchuck, he is first tempted to seize and devour the creature raw “for that wildness he represented.”[13] But Thoreau questions this reasoning, asking whether something once alive can transmute its life force in death, or whether, in fact, what ends up being transmitted is death and decay itself. I remember the burned-out cathedral of the chicken carcass after the weekly roast that punctuated my childhood, a nightmare necropolis sitting in pools of fat that could have been dreamed by H.R. Giger. In Bennett’s essay, “Thoreau ultimately concludes that ‘devouring’ wild flesh does not in fact result in his own vitalization, but in the mortification – the rotting – of his imagination.”[14]

Lack of imagination is illustrated by one of the local farmers he comes across, who tells him “You cannot live on vegetable food solely, for it furnishes nothing to make bones with.” Needless to say, this meat-eating man employs sturdy oxen to do the work he is not built for, “which, with vegetable-made bones, jerk him and his lumbering plough along in spite of every obstacle.”[15]

~

In Eric Rohmer’s film Le Rayon Vert (The Green Ray, 1986), Delphine is young, recently dumped and at a loose end in Paris over summer. Slightly superstitious, she finds a green playing card in the street, and decides that green will be her color for the year. She travels to Cherbourg to stay with friends, but spends most of her time wandering in the woods, and trying to defend her vegetarianism to her skeptical companions. She’s the odd one out, so she returns to Paris, then travels to Biarritz, but revolts against the shallow antics of sex-hungry singles she meets there. She does, though, overhear a conversation on the beach about the phenomenon of the green ray, or green flash that occurs when one watches the sun set over the sea. Leaving Biarritz, she meets a young man at the train station, and impulsively, decides to stay to watch the green flash with him. The final sequence is the sun sinking into the sea; a green ray envelops the screen.

Eric Rohmer’s Le Rayon Vert (The Green Ray), 2008. Spoiler: it all ends in a flash of green over the sea.

Some might find Delphine irritating. Certainly she is neurotic, a misfit, regularly bursting into tears, running away from social situations, and blurting embarrassing phrases like “lettuce is my friend.” But I understand the loneliness she feels in staying true to her principals. The people around her are perfectly normal and nice. They don’t victimize her. Neither do they understand her. It is hard being a social animal with anti-social ideas. Being vegetarian, and childfree by choice, my radical abstinence puts green glass walls between my friends and me. I want to feel fellowship with humanity, but my only fellowship is with other misfits, other conscientious objectors.

~

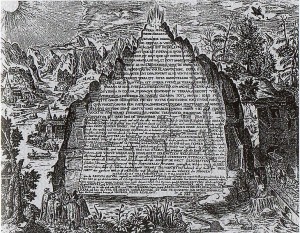

Green is the color sacred to Islam. Not the red of the blood that runs in our veins, or the blue vault of the heavens, but green, the oasis that gives succor in the desert. Cult writer Peter Lamborn Wilson, a.k.a. the Sufi adept Hakim Bey, eulogizes the Emerald Tablet of Hermes Trismegistus in his essay “Green Hermeticism.” A Greco-Egyptian text, preserved only in Arabic, it is the origin of the phrase “As above, so below” and the “Hermetic doctrine of correspondences between micro- and macrocosm” so beloved of tripped-out information junkies such as Wilson himself, and the science fiction cult hero Philip K. Dick. Wilson describes an engraving of the Tablet by the German alchemist Heinrich Khunrath from 1602:

We see Hermes – who began his career as a shapeless rock or heap of stones in the corner of some Arcadian meadow – depicted in the form of an emerald mountain of words. Taoist sources mention a remote cliff face at which one must stare unceasingly for three years, whereupon a strange spirit-written script will finally be discerned in the very lithic sinuosities that mock and elude the act of reading. This text is/was/will be scripture unmediated by consciousness, an irruption of language in nature – text as miraculous initiatory force. Khunrath has imagined not only the very shape of the mystic peaks of Taoist landscape paintings, but also the very shape and function of the Rosetta Stone long before its discovery.

Sol as Hermetic godhead sparks emerald fires from the mountain (which, as rock, is a type of sal). These green sparkles are letters and words, metaphors that carry across some paralinguistic flash from the world of meaning to the world of expression. Green fire is Green Hermes, a link between nature as speechlessness and Natursprache as “spell,” as mantric/semantic communication, the spark between you and me, or you and some tree.[16]

The Emerald Tablet, beloved of mystics and seekers. Not to mention Philip K Dick.

~

Natursprache is nowhere more evident than in the parrot, and in New Zealand, the kaka, kakapo and kea are the oldest living forms of parrots on the planet, veritable ur-parrots. The kea is exceptionally cheeky, a mountain parrot that will destroy your tent or your car with its sharp beak, just for fun. Even the kakapo, the giant nocturnal ground parrot, horribly close to extinction, proved not to be the retiring type when it tried to mate with zoologist Mark Carwardine’s head in a BBC documentary about endangered species narrated by Stephen Fry.[17] Paul Carter imagines the world before the advent of talking monkeys, saying, “This lost, pre-linguistic world is not speechless, enveloped in eerie silence. It is alive with the primary colors of language, clicks, squawks and whistles, the ‘first scream of the flesh,’ a kind of all-speak.”[18]

Carter, who is a historian and an architectural theorist, wrote an intriguing book on the parrot as part of Reaktion Books Animal Series, link] in which he suggests, “We persist in thinking that parrots merely mimic us, when their mimicry is a way of telling us that we are mimics.”[19] Parrots are the totem for humans devoted to language, not to mention language devoted to color. But the word psittacine, of or relating to the family of Psittacidae, has come to mean the ability to talk without knowing or understanding. According to Carter, the etymology is from the Greek psittakos via the ancient Sanskrit suka, which is still the word for the common green parrot in India today.[20] Kama, the Indian god of love, rides a green parrot. Like cupid, he shoots arrows causing affection affliction, or tenderness, only his arrows are made with sugarcane and the bowstring is a line of bees.

Carter sends up the ur-word Ka, the Ancient Egyptian spirit double, or the first word of Hindu mythology, which becomes “the parrot’s own squawked ca-ca” – Italian baby-talk for ‘poo.’[21] He notes that in the foundational myths of many cultures, parrots are responsible for introducing and protecting both language and color, as if they are twin strands of the same stuff. This “irruption of language in nature” introduces difference into the world, which can be envisioned as the Biblical parable of Babel: loss of unity and the subsequent reign of confusion; or it can be celebrated as the moment consciousness was born.

In La Historia de los Colores/ The Story of Colours, Zapatista spokesman Subcomandante Marcos retells a classic folktale from the Chiapas region of Mexico, as to how colors came into the world. Various gods created colors in an effort to make the world more interesting for its inhabitants. The gods put these colors in a box, but they escaped and started to make love to each other, and more colors were made. When the gods discovered this, they weren’t angry, they joined the party and started flinging color about too, like the Holi festival in India where people mimic the lovemaking of Radha and Krishna by throwing colored powders at each other. “And,” Marcos writes, “it was a mess the way the gods threw the colors because they didn’t care where the colors landed.” In his story, colors falling randomly on people is the reason there are “peoples of different colors and different ways of thinking.”[22]

The macaw – the brightest parrot in the rainforest – is charged with the task of preserving all the world’s colors on its body “just in case men and women forget how many colors there are and how many ways of thinking, and that the world will be happy if all the colors and ways of thinking have their place.”[23]

~

The Secret Life of Plants (1973) is the apogee of the Western understanding of the vegetable mind. Written by Christopher Bird, a science journalist who served in the US Army, and Peter Tompkins, a war correspondent and Secret Service officer, this is pop science at its weirdest and most wonderful. They start gently, enumerating various botanical wonders, such as that a eucalyptus can grow as high as an Egyptian pyramid, that a walnut can produce 100,000 nuts in a season, and Indian liquorice trees can predict cyclones.[24] They go on to discuss Cleve Backster, a polygraph expert whose potted plants reacted at home when he showed their images during slide lecture tours, and Pierre Paul Sauvin, a scientist from New Jersey who “hooked his plants to an oscilloscope, a big electronic green eye with a figure eight of light whose loops changed shape as the current from plant varied, making patterns much like the fluttering of the wings of a butterfly.”[25]

The Secret Life of Plants by Christopher Bird and Peter Tompkins with cover by Alan Aldridge.

Sauvin found that plants reacted strongly when he hurt himself, and “on holiday with a girlfriend at his cottage he established that his plants, eighty miles away, would react with very high peaks on the tone oscillator to the acute pleasure of sexual climax, going right off the top at the moment of orgasm. “All of which was very interesting and could be turned into a commercially marketable device for jealous wives to monitor their philandering husbands, by means of a potted begonia…”[26] This is possibly the best segue in the history of the published word. The Secret Life of Plants is filled with sex, vegetable and animal, telepathy and even a sort of telekinesis:

To include his beloved plants in a worthwhile gadget, attractive to car and home owners, Sauvin worked out a system whereby a man returning on a snowy night could approach his garage and signal his pet philodendron to open the doors.[27]

The book’s more outlandish claims are written in a language of dry reportage which makes them all the more surreal:

In a room near Maida Vale there is an unfortunate carrot strapped to the table of an unlicensed vivisector. Wires pass through two glass tubes full of a white substance; they are like two legs, whose feet are buried in the flesh of the carrot. When the vegetable is pinched with a pair of forceps, it winces. It is so strapped that its electric shudder of pain pulls the long arm of a very delicate lever which actuates a tiny mirror. This casts a beam of light on the frieze at the other end of the room, and thus enormously exaggerates the tremor of the carrot. A pinch near the right-hand tube sends the beam seven or eight feet to the right, and a stab near the other wire sends it far to the left. Thus can science reveal the feelings of even so stolid a vegetable as the carrot.[28]

In 2005, along with fellow Masters student Helge Fassonaki, I pretended to experiment with plants. We wanted to create the look and feel of the lab, wearing white coats, and plunging copper wires into the soil of potted plants, attaching the other ends to our temples and attempting some sort of mind-meld. We weren’t the only artists to be inspired by the pseudo-science of the Secret Life of Plants. As part of the GardenLAb Experiment, in Los Angeles, 2004, Matias Viegener and David Burns unveiled their Corn Study, in which corn plants were played audio tracks, while electric fans were set behind open books so that they could “carry knowledge through the air like pollen.”[29] For, as Thoreau asked rhetorically while gardening in Walden, “What shall I learn of beans or beans of me?”[30] Thoreau describes his puttering among plants and soil as “dabbling like a plastic artist in the dewy and crumbling sand…”[31] which confirms my suspicion that gardening is a form of art. Or perhaps it is more accurate to say that we “curate” plants? That would mean the plants themselves are the works of art.

Artists Matias Viegener and David Burns, GardenLAb, LA, 2004.

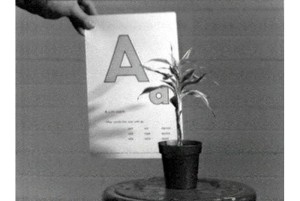

Viegener and Burns were no doubt referencing the utopian science of The Secret Life of Plants, but they were also paying tribute to California conceptual doyen John Baldessari, who made a video called Teaching a Plant the Alphabet in 1972. Baldessari himself was referring to Joseph Beuys’ ineffably poetic performance, How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare, from 1965. The great divide between the languaged and the un-languaged is, in Baldessari’s video, made tenderly manifest. A small potted plant is shown alphabet flashcards by the artist, and the letter in question is intoned over and over, in a voice both patient and patronizing, like every teacher and parent. Repetition is the key to retention, but surely this is futile, delusional, and also horribly paternalistic? Why would plants want or need our language? They have far more ancient, subtle networking systems than our clumsy monkey chatter. And yet, there’s something beautiful about this interspecies outreach. It is, at least, an attempt at communication, albeit a wry, tongue-in-cheek one.

John Baldessari, Teaching a Plant the Alphabet, 1972.

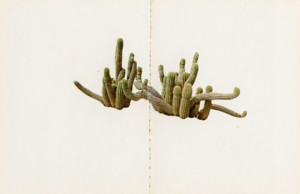

In the same year, Los Angeles pop conceptualist Ed Ruscha published Colored People, a small book full of images of plants. The implied racism of the title is somewhat relieved by the joke that this is a botanical handbook. By eschewing text altogether, Ruscha, that most textual of artists, momentarily renounces language as a tribute to the non-verbal consciousness of the plant kingdom.

~

Burroughs’ Ghost of Chance is about a paradise not so much lost as bludgeoned to death. The first blow was struck when the nature god Pan died, according to Burroughs, on December 25, year zero A.D.

“And what is Panic? The realization that everything is alive.

The great god Pan is dead.”[32]

Burroughs envisions a world in which the animal and the vegetal copulate and mutate in ways both liberating and terrifying. Diseases turn people into plants. Roots burrow through intestines, and a skull becomes “a flowerpot for stunning brain orchids that grow over dead eyes and idiot face while the skin slowly toughens into bark.”[33] The over-poppylated brain of Burroughs imagines:

A plant man who grows from one place to another, festooned with lethal orchids and stinging vines; an electric-eel man, six feet of sleek brown-purple with mud-cool green-brown eyes: both hermaphroditic, fertilizing themselves and giving birth… A vegetable consciousness that moves through the forest, feeling its way into trees and vines and orchids, and looks like a green jellyfish floating in a green medium… A dog creature with a vine tail and thorn teeth… Intelligent birds, of a light porous texture, like sponges…[34]

Then, Burroughs imagines a sect of “Green People” who develop photosynthesis, “converging in calm green swirls and eddies. Some take to water, develop gills, and live on algae. Some nourish themselves on odors, which they breathe in through pores that they can open to the size of a match head. Others eat light and color so that their bodies finally melt into light.”[35]

As Delphine said in Romer’s film, “Lettuce is my friend!”

McKenna wrote a manifesto for greening human consciousness called “Plan, Plant, Planet,” which first appeared in the Fall 1989 issue of the Whole Earth Review. The first step in embracing the “gnosis of the vegetable mind – the Gaian collectivity of organic life,” as he put it, was to re-embrace the archetype of the Goddess and feminize culture. The second step is “inwardness,” being the characteristic approach of the vegetable as opposed to animal existence. “The animals move, migrate, and swarm, while plants hold fast. Plants live in a dimension characterized by the solid state, the fixed, and the enduring. If there is movement in the consciousness of plants then it must be the movement of spirit and attention in the domain of the vegetal imagination.” I think of my devastatingly shy love, and of the Buddha achieving enlightenment by sitting very still for a very long time, perhaps, not surprisingly, under a tree.

A group of Thai priests wrapped saffron robes around rainforest trees and ordained them to be Buddhist monks in order to stop logging[36] – an act of associative magic or perhaps downright pragmatism that makes Anahatha burst with hope and hopelessness. They tie these saffron robes like that eight-foot rope was tied between two performance artists, as a symbol of interconnectivity. Male, female, plant, animal – we may speak different languages, but we can’t live without each other.

Ed Ruscha, Cactus from his series 1972 Colored People.

[1] Mookerje, Ajit, Tantra Art: Its Philosophy and Physics (New Delhi: R. Kumar), 1983, 15.

[2] Houston, Stephen, et al. Veiled Brightness: A History of Ancient Maya Colour (Austin: University of Texas Press), 2009, 78.

[3] Burroughs, William S. Ghost of Chance (London: Serpent’s Tail), 1995, 17.

[4] Grey, Alex and Allyson Grey, “The Year of the Rope: An Interview with Linda Montano & Tehching Hsieh,” in Letters from Linda M. Montano, edited by Jennie Klein (London; New York: Routledge) 2005, 45.

[5] Birren, Faber, Colour Psychology and Colour Therapy: A Factual Study of the Influence of Colour on Human Life (New Hyde Park, New York: University Books), 1961, 9.

[6] Grey and Grey, 40.

[7] Ibid, 41.

[8] Ibid, 47.

[9] Van Gogh, Vincent, Dear Theo: The Autobiography of Vincent Van Gogh, edited by Irving Stone (New York: Doubleday), 1946, 523.

[10] Thoreau, Henry David. Walden, Or Life in the Woods (New York: Dover Publications), 1995, 198.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid, 201.

[13] Bennett, Jane, “Edible Matter,” New Left Review 45, (May-June 2007), 141.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Thoreau, 5.

[16] Wilson, “Green Hermeticism,” 58.

[17] This was Sirocco, one of only 128 surviving kakapo, and consequently, the ‘rock star’ of his species.

[18] Carter, Paul, Parrot. London: Reaktion, 2006, 110-111. Funnily enough, in a dusty old bibliography at the back of one of my source books, I found a French book about the Tower of Babel, the coloured ziggurat which signalled the end of all-speak, written by none other than “A. Parrot”: Parrot, André ,Ziggurats et Tour de Babel (Paris: Albin Michel), 1949.

[19] Carter, Parrot, 8.

[20] Ibid, 45.

[21] Carter, 113-114. In pun-riddled Māori, kaka is both shit and parrot.

[22] Marcos, Subcomandante, La Historia de los Colores/ The Story of Colours (El Paso, Texas: Cinco Puntos Press), 1999, unpaginated. By contrast, traditional tales of colour and parrots from the Amazon as catalogued in Levi-Strauss’s The Raw and The Cooked involve bludgeoning and guts.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Bird, Christopher, and Peter Tompkins, The Secret Life of Plants (Penguin Books, Middlesex), 1974, 11-12.

[25] Ibid, 29.

[26] Ibid, 31.

[27] Ibid, 32.

[28] Ibid, 92.

[29] Viegener, Matias, and David Burns, “Corn Study,” GardenLAb Experiment, www.fritzhaeg.com/garden/initiatives/gardenlabshow/participants/viegenerburns.html. Accessed 28 December, 2011.

[30] Thoreau, 101.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Burroughs, 25.

[33] Ibid, 47.

[34] Ibid, 52.

[35] Ibid, 53.

[36] Balick, Michael J., and Paul Alan Cox, Plants, People and Culture: The Science of Ethnobotany (New York: Scientific American Library), 1996, 167.

”

Green, though, is the heart of the spectrum if we start in red and end in violet”

I do not agree: http://www.mathiasbfreese.com/2014/11/ Friendly, Lindy