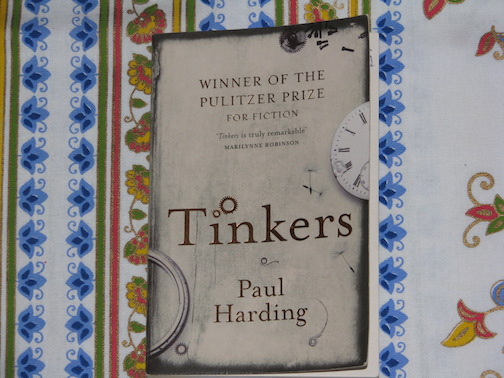

PAUL HARDING’S NOVEL Tinkers holds a special place in my heart because it was the first novel published by an independent press to win the Pulitzer Prize (2010) since John Kennedy Toole’s A Confederacy of Dunces in 1981. Also, since Harding was once a professional drummer, it’s the first Pulitzer in fiction ever given to a writer/musician. As a writer/musician myself, it was good to see one of my own crowned with such a cool accomplishment. I didn’t even let it bother me that a drummer had won it before a bass player.

What surprised me was a quote I read from Harding at the online magazine Howl. When asked how playing music influenced his writing, Harding said, “I think that all art comes from the same place and it’s just a matter of what medium you use to express it. So, when I played drums, I tried to articulate what creative signals came over the wire in rhythm. Now, I do the same thing but use words.”

Before I respond to this quote, let’s make a few things clear. Paul Harding found a publisher for his novel; I’ve finished three novels, and have never found a publisher for one. Harding is a Pulitzer Prize winning novelist, I have not won the Pulitzer Prize. Harding was a teacher/writing fellow at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. I teach the nuts and bolts of self-publishing at whatever institution will have me. Paul Harding probably makes some kind of a living as a fiction writer, and I make, you might say, less than that. In short, Paul Harding has won this game in just about every way, and I have lost it.

But Paul Harding is crazy if he expects me to believe that writing a novel is anything like playing the drums. I’m sorry. It’s not.

I started playing music the summer after I turned fourteen years old. That summer (1983) I gave up my dream of becoming a professional baseball player. (Suffice it to say someone who’s afraid of the ball isn’t going to wind up on the Cubs.) In a few months I’d start high school, and central to my concerns about this change was how I’d get girls if I weren’t an athlete. Without baseball, I seemed a formless mass. It scared me to think what might shape me if I weren’t proactive about shaping myself.

The answer to this issue came in the form of a sunburst Hondo II bass guitar I bought with money I’d made painting a picket fence. The bass was big, unwieldy, and didn’t yield any of the sounds that came from the Van Halen and Led Zeppelin records I’d just started listening to. I took lessons but barely practiced. Then, about six months later, someone showed me the bass line for Quiet Riot’s “Metal Health,” and I was off to the races.

It was a relief to find that, unlike baseball, I actually had some ability at the instrument, what I’ll call a “basic rhythm” I’d taken for granted most of my life. A few of my friends didn’t have this necessary ingredient, which created awkwardness when we sat down to jam Iron Maiden tunes. All those years of going to baseball practice I now realized had been fruitless. I was never going to be an athlete, but I could do this.

I dedicated the first five years of my bass playing life to learning everything I could about the instrument. I learned to use one finger per fret with my left hand, and to alternate fingers with my right. I learned music theory, scales and arpeggios. I learned any song anyone would teach me, and eventually I learned to pick them up myself.

When I was nineteen, local drummer Damion asked me to try out for his band. I was a big REM fan at the time, and I asked Damion if there were any chance we could play some REM covers.

“No,” he said. “We play all original music.”

I was shocked. He—we—somehow didn’t seem qualified to play original music, but I took the tryout anyway, hoping I could talk them into some REM tunes later.

Once I got in that basement and got my first taste of playing original music—using the theory I’d learned to make up bass lines for the band’s songs—I was sold. I joined the band on the condition we never, ever play a cover song.

That tryout marked the end of my learning period on the bass guitar. I was now a music writer, a composer. When I showed up to band practice, I didn’t think about musical theory. I only cared if what I played “sounded good.” I never played a G major scale when our guitarist played a G major chord. That would sound too obvious. Still, G major had been hammered home for me from years of playing those scales, and I understood implicitly which notes went with which chord. I was doing what I believe Harding means when he says, “I tried to articulate what creative signals came over the wire in rhythm.”

As I played in original bands over the next decade, making my living in one for the last five years, I got bored with bass guitar. It more and more felt like a limited mode of expression. Of course, the bass wasn’t really limited as an instrument as much as I was limited in my patience for learning about it. I felt I could do two or three things well on the bass, and I didn’t want to go back to the woodshed for months or years to come out a newly refreshed player.

Besides, a new mode of expression had been making itself known to me for years. I’d been obsessively reading novels since my college days, and wanted to try to write one. In the waning years of my life in bands, it was time.

My approach to learning to write a novel was a little different from my approach to learning bass guitar. When I was fourteen, I started from scratch as a musician. I couldn’t remotely “form a sentence” on the instrument. My first five years of bass playing were about learning the language of music. At twenty-seven, I knew enough about the rudiments of the language to take a swipe at writing stories. Novel writing was more complex than that, of course, but there seemed no other option but to jump right in.

I started simply. I wrote two pages per day, five days a week, which led to ten pages per work week. At that rate, going on the belief that my novel would need to be about 250 pages, I’d have enough in six months. I worked diligently every morning getting the words down. Sometimes I made sure to get half a page every half hour. Other times I’d screw around, realize it was getting late, and rush to meet my quota. At the end of six months, I had my 250 pages, and I printed them off, sat in a comfy chair and started reading it.

And was embarrassed for myself.

The book was so egregiously wrong I could barely stand it. The characters were flat. Plot lines were started then completely abandoned. Huge emotional issues were ignored while unimportant, minute details were gone over ad nauseum. I don’t think I got ten pages into the thing before I dropped it in a recycle bin.

To equate this portion of my writing life with my nascent time composing on the bass is on one level accurate. In both instances I was taking blind stabs at what might work with my chosen mediums, but it’s also misleading. On bass, I came up with something at least palatable the instant I tried to write a line for an original song. With novel writing, after years of learning the basics of language in school (I’d even majored in English in college), and after working diligently for six months specifically at the novel form, I couldn’t bear even to “listen back” to what I’d done. I might conclude from this that I was just far more talented at composing bass lines than I was at novel writing, or I might conclude that the process of novel writing is a lot harder than the process of writing bass lines. I know where my money is.

Most striking to me is the amount of time I’ve dedicated to novel writing when compared to bass playing. My regular weekly allotment of novel writing is consistently, religiously, ten hours. In the decade when the bass was my primary outlet, there were days I dedicated two hours to it (band practice), but there were days I didn’t play at all. During a normal week as a professional musician, I played maybe five hours. When we’d tour, we played five or six nights a week, and sometimes for more than an hour a night, so you could say I approached ten hours a week while on the road. But just as common were long periods at home with maybe one band practice and one gig per week—three or four hours of playing. And I rarely played by myself, unless I was recording bass to accompany songs I’d written on my four-track. I’m not saying I was a slouch; this all strikes me as fairly common for a pro or semi-pro rock musician at the time. By the end of my last band, my relationship with my bass was largely utilitarian. It was a tool from which I’d made my living. Music as my primary passion was over.

Something more monkish was going on with novel writing. I pushed myself to try and write as well as my heroes: Faulkner, Hemingway, Vonnegut, Beckett. I came up short, but with each draft I got to know my craft—and myself—a little better. I self-published my first novel in 2003, and I’ve since done the same with two more novels, each taking about five years of this disciplined approach. During that time, my relationship to the form has only grown. I still dedicate at least two hours a day to fiction, and only now do I feel like I’m starting to get the hang of it. For me, bass playing didn’t and doesn’t “come from the same place” as novel writing. It wasn’t not just a matter of what medium I chose to express my inner yearnings. These two crafts got me to two distinct places in just about every way. I now think of bass playing as a middle step between the activities of childhood—say, riding a bike—and the more nuanced craft of novel writing.

I don’t bring this up to dis bass playing—which was and always will be my musical home—or Paul Harding—whose work deserves your attention—but to correct any misunderstanding Harding’s quote might conjure about these two modes of expression. Maybe every writer should be to be able to thump out a novel on a keyboard the way a drummer thumps out a song on his skins. In my almost two decades of novel writing, I haven’t found that to be the case. If anything, the act of learning pop music, its more manageable breadth, might make a musician expect other modes of expression to be just as easy, and thus give up when a first attempt doesn’t yield a masterpiece. If you’re a musician ready to take the plunge into novel writing, don’t be surprised if your new craft takes more rehearsal.