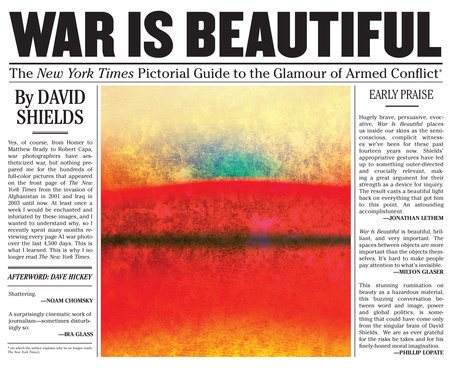

David Shields’ collage attack on the New York Times—War Is Beautiful: The New York Times Pictorial Guide to the Glamour of Armed Conflict–is, quite simply, required reading.

This collection of photographs cut from the Times‘ front pages during this, our era of endless war, makes a visual argument that, told without images in a traditional essay, might sound more like a conspiracy theory than a fact. Shields, and War Is Beautiful, present the Times as aesthetically inflected warmonger: in making our wars beautiful, the paper of record amplifies the argument for military intervention. This book is a collage attack, and the most-effective example of the collage direction Shields has embraced in recent years.

We spoke by phone in an edited transcript below, but not for the first time. I blurbed War is Beautiful, although in truth forgot about doing so for the much less-impressive proof copy I saw some months ago. When the finished book arrived, my cultural amnesia quickly dissipated.

~

[Shields answers phone. We exchange hellos and pleasantries. We chat about my stint at Associate Dean of the Faculty at Lake Forest College.]

Shields: It’s great. You’re more of a citizen scholar than I am. I’m just a totally selfish, worker bee creating my little mini projects.

Schneiderman: I turned 40 and had this big crisis: Why write anymore? I’m still writing, but I’m also working my way through that question. Too much quasi-conceptual work [my recent novels] isn’t so good for the romantic, creative spirit…which I’m completely skeptical about anyway.

Shields: I know, I really liked that exchange we had for The Writer’s Chronicle (Dec. 2014)–“Pull Any String of the Spider Web and the Whole Thing Vibrates: An Argument/Conversation.” That was a really good exchange.

Schneiderman: It was fantastic, but let’s talk about War Is Beautiful. I have been reading it over the last couple of days. It’s amazing. The production values alone are fantastic.

Shields: I agree. Someone called it “museum quality.” You could almost mount it as an exhibit….You can get it on Amazon for $28, but the asking price is $40….The permission fees weren’t so bad. The publisher took care of all that and the permission fees through the photo agencies were relatively moderate, I believe.

Schneiderman: So that’s the first place to start. Did anyone not give permission? Have you heard from the New York Times? Has there been any push back?

Shields: I actually had 700 photographs to choose from, from October ’97 until now. It seems as if once or twice a week there would be a color combat photo that fell into the glamorizing realm. I think I got it down to around 150 at one point. Almost no one said no. A few obscure photo agencies in the Middle East never got back to us, but we weren’t aware of anyone specifically saying “absolutely not.”….I had a huge cache of pictures to choose from so these were among my very favorite 64.

Schneiderman: And the Times?

Shields: They requested a few copies. I think they finally have a copy now….I don’t know if they’re going to review the book.

Schneiderman: That would be their smartest move, right? They could put their own narrative spin on it, and blunt the book’s criticism.

Shields: It’s an interesting question. Do they ignore it? Part of this project for me was that this is a liberating thing to do as a writer: You know, one is not supposed to criticize the New York Times, let alone over the course of a full book, which is, in my view, a rather searing and persuasive critique of the paper. It was almost a dare to myself.

I’ve been noticing this pattern over many years, and when I tell my friends they roll their eyes….I think of that Department of Homeland Security line, “If you see something, say something.” I felt like I was definitely seeing something–the falsely gorgeous images of war, painted, almost invariably, in Times combat photos. As a citizen, as an artist, as a human being with a conscience, as someone who likes to create friction and questions, I felt on some level that if I’m in any way a serious writer or thinker, I had to take the plunge and do the book. And I was obviously thrilled the publisher had the nerve and capacity.

Schneiderman: There are many publishers who wouldn’t touch this with a twenty-foot pole. You’ve got lucky with Powerhouse.

Shields: I think they did a beautiful job….Yet many other publishers came up with pseudo reasons not to publish it like, “Oh, I think you’ll have legal problems …” It was so relatively transparent that they did not care to antagonize the New York Times. I’ve always liked this idea that writing should comfort the afflicted, and afflict the comfortable, to create trouble. The value of a work of art can be measured by the harm spoken of it. If you’re not feeling that, then absolutely, why bother?

Schneiderman: I anticipate this critique of the book: You’ve identified this pattern, but by reproducing the images and reproducing them beautifully and creating this beautiful package and putting your name on it, you are the curator, and you are also exploiting the suffering of others, even though it happened first in the Times.

Shields: I think that’s a great critique. First of all, I doubt I’ll make much of any money on this. I was paid a very modest advance and what little I got I poured back into, frankly, the production and dissemination of the book. So it’s not like it’s going to be some huge financial thing. It’s more like an indie documentary that you hope to just get out there.

Second of all, I would say I don’t feel at all guilty as charged, in the sense that this is the same critique of Reality Hunger: A Manifesto [a book, in part, of quotations]. I do think we’re all complicit. If this is only a sort of wagging finger at the terrible New York Times, then the book fails. The book means to find us all guilty of charge as we lead lamb to slaughter.

I should have published this book ten years ago. It took me too long to gather it, too long to get it done, too long to realize the pattern, to long to pull the trigger. We all felt in swoon to these pics and we all gobbled them up as “war porn.” And if I, or the publisher, is slightly benefitting from it, I think that’s an interesting layer. I mean, the book is meant to be disturbingly beautiful….It’s a kind of sweat-inducing, guilt-enhancing coffee table book in which some of the pictures are just ferociously beautiful.

Schneiderman: Completely.

Shields: What was that?

Schneiderman: I said, “Completely.” And my little quote on the inside flap is, “Fantastic, engrossing, and gruesome. I love it.” So, I too have swooned.

Shields: “Fantastic, engrossing, and gruesome.” I mean, a huge part of me hugely admires these photographers for taking these stunningly beautiful pictures. They’re just so compositionally beautiful.

You could say there’s all sorts of reasons as to why the Times is running these incredibly beautiful pictures. If all they’re doing is promoting Times Square or they’re showing houses in Connecticut for real estate porn, then okay, but the war, human beings’ lives… you know there are estimates that as many as 400,000 people, civilian and military, have died directly or indirectly from the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. I think these pictures have done their part to demonstrate an environment in which war is viewed as glorious and gorgeous and beautiful and definitely worth doing.

Schneiderman: Well, it leads to this other question: How should the Times be pictorially covering these events if not in this way? Is there any way that one can do it that doesn’t trivialize or glorify or amplify the “beauty” of war?

Shields: That’s a good question and people have definitely asked me that: “OK smarty pants, but what’s your answer to how these pictures show up?” A few things come to mind. There is there is a great tradition of war photography, from Mathew Brady through Robert Ellison in Vietnam and Larry Burroughs in the Tet Offensive in Vietnam, in which pictures convey the truth. They still have compositional beauty perhaps, but they convey the absolute, irreducible cost of war and they show absolutely naked groups of men. Second of all, there’s a line of Susan Sontag, and she’s talking about a World War II photograph of concentration camp victims. I think she was around twelve or something when she saw the picture. She writes: “This photograph broke me,” or “This photograph lacerated me and I’ve never recovered from that photograph,” which is sort of typical Sontag overstatement.

Yet I think the idea of a picture that lacerates is a useful model when it comes to the cost of war. I think of these pictures as not “war as hell” but “war as a very pretty heck.” In these pictures war seems like heck, it doesn’t seem like hell.

Schneiderman: There’s a number of interesting things in what you’re saying–I was several weeks ago in Krakow and went to Auschwitz-Birkenau, as part of a site-specific performance I was doing for European Beats Studies Network conference. In Auschwitz I, which are pre-WWII army barracks-turned-museum, you see a array of blown-up victim photographs.

That’s what the museum is; you’re in the death block; you’re in the cell block, and you’re seeing the image. To take that image of suffering and stick it right on top of the place where it happened….whereas, in the Times, of course, with your ads and your real estate porn, the image is completely de-contextualized from its source. It’s swimming in commodification. I wonder if these images would mean something different to those living in the space of atrocity–and maybe the images haven’t been shown in that space. Maybe the victims in Iraq have never seen these images.

I’d be curious to know if that context would change it all and what you’ve done here. You’ve gallerized these photos. You’ve turned them into museum pieces, which they are. You’ve given them a lot of white space, you and the publisher. You’ve created breathing room by stripping away all the crap in the newspaper that surrounds an image. And, all of those things are fascinating.

Shields: In the inside back cover of the book is a two-page spread of 64 thumbnail full front pages of the original Times, which are among my favorite two pages of the book. These are stunning images where you can see how much the Times is trying to balance things….I’m sure the Times is trying hard to maintain a foothold in the digitized world in which they find themselves, but I think that amongst their many concerns is, you know, the compositional perfection of the page.

I think they’ve afterwards done a really good job of explaining how so many of these photographers are basically producing modernist painting masterpieces, sort of second generation…it’s funny I said “painter.” I meant “photographer.” Yet the photos are a kind of second-rate Robert Rauschenberg, second-rate Jasper Johns, second-rate Jackson Pollock, second rate Mark Rothko.

(Directs Schneiderman to a close-up of two bullet casings.) It’s a beautiful image of those two bullets that was actually from a much larger picture which the Times cropped down to produce a total abstract work of stunning visual beauty. Yet the overall picture looked nothing like the compositionally beautiful final image. Part of the critique is that the photographers and the photo editors have gone to school, all too carefully, to be modernist painters. They’re producing kind of corporate folk art rather than war documentaries.

Schneiderman: There’s a kind of constellation effect at work in the full-page thumbnails. Often, we have war image and a talking head kind sharing different parts of the front page. You’ve got blood dripping from the car in the war photo, and I can’t tell who that is, but it’s spilling down the page on (maybe) Mitt Romney. There are unintentional juxtapositions.

Shields: Look down on the left corner: We’ve got the New York Yankees scoring a winning run or something. If we had a truly lacerating photograph, it would just disturb the viewer.

Schneiderman: That’s your argument: there’s a limit to any possibility of “laceration.” You can’t be broken from the plain of the paper because, structurally, the paper–the people who run it, the people designing it, the photographers–not one of them can break through the limits of the business they are in.

You can say, “I don’t like the Times, they are too much this or too much that. ” But those are all opinion-based or content-based arguments where people, as you said, can roll their eyes when you say it. But this collage, this juxtaposition, is the best and most powerful way to demonstrate the problem and puncture it.

Shields: Thanks, that means a lot to me. I liked the rigor of your analysis in general and if this were The Wall Street Journal, you would say there’s no book. Or if this were USA Today, The New York Post, The Daily News, or any number of right-wing papers…but the Times….the Times is understood to be almost the unofficial biographer of the country, in some strange way to be printing a kind of quasi-neutral truth or even, in some people’s minds, slightly center-left version of reality.

Yet if you look at these pictures, these pictures do not seem the repository of a newspaper that is studying the war or even being skeptical about it. This feels to me like flag waving, cheerleading….It’s a kind of bat signal. Here is the war, but really, here is the war beautiful.

Schneiderman: These are stills from an unmade Leni Riefenstahl film.

Shields: Oh, now that’s beautiful.

~

Many thanks to Lake Forest College students Sydnie Bivens and KeAthony Thompson for transcribing this interview.