“UNDINE SPRAGG – how can you?” is the enigmatic opening sentence of The Custom of the Country, Edith Wharton’s highly successful 1913 novel. Met with critical and popular acclaim in its day, it nonetheless “stands just outside Wharton’s triumvirate of best-known” works: The House of Mirth, Ethan Frome and The Age of Innocence. The execrably-named anti-heroine, whose self-serving behavior makes her name as apt as it is unappealing, spends the entirety of the novel affirming the effrontery of the opening sentence. Given Ms. Wharton’s penchant for irony, it is no surprise that the nymph-like creature who is the focus of the novel bears the initials “U.S.”

The Custom of the Country has been sitting on my “to be read” shelf for almost a decade. Though I have worked joyously through some of Wharton’s other works, Custom always seemed to beg for the right moment. I was contacted by the Communications Director at The Mount in Lenox, Massachusetts, to write an essay for the 100th Anniversary of the novel’s publication. In celebration of its centenary, the novel is being republished in serial format as it was originally published in Scribner’s Magazine, each installment accompanied by an essay. I figured this was a sign that I should read the book.

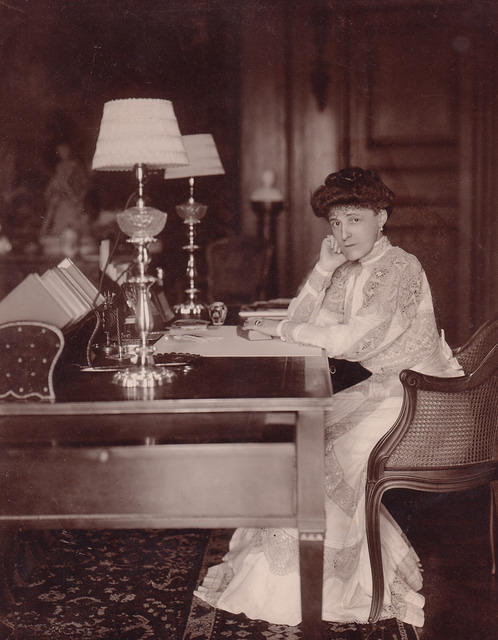

Incidentally, I’m a great fan of Wharton and have visited her former home in Lenox, MA many times. The Mount, designed by Wharton according to the theories of her 1897 book The Decoration of Houses, was her home from 1902 until 1911 when she sold it and moved to France. It is now a museum.

Having turned the final page on The Custom of the Country, I’m convinced that Wharton’s examination of old America would have stirred me just as easily if I’d read it on that day I returned with it from my local bookstore. Wharton, whose interest in the unseen world influenced her ghost stories and led her to believe The Mount was inhabited by others than herself, was as empathic as she was prescient. The themes and situations of The Custom of the Country have reached a zenith in the second decade of the new millennium where reality programming and the 24-hour news cycle lend illusory credibility to celebrity status and monetary measures of “success.” Undine Spragg, you see, spends the entirety of Wharton’s sly-eyed view of American obsession climbing over everyone and everything on her way to vague pinnacles of social glory.

A friend I have known for almost three decades recently berated me after a hurried series of e-mails about a professional opportunity, “…you might,” he wrote in an unpleasant e-mail, “want to suspend your uninformed biases of people based upon the job they fill particularly if you wish to take advantage of the significant social and professional capital they carry and control.” The details of our disagreement are unimportant but his diatribe reminded me of something a character from Wharton might say in a rare moment of direct anger (Wharton’s people mostly move about in simultaneously discreet but assertive ways; flashes of anger are rare.) What shocked me about the encounter with my friend was not that he misunderstood my question but that his parry belied his feelings about social hierarchy. The phrase “taking advantage” may be apt but I’d never seen a professional inquiry in quite those terms. What echoes through his reprimand is an investment in a world in which social capital produces calculable dividends but where every misstep is a potential bankruptcy.

What has changed, then, in the century since the publication of Wharton’s novel?

Social media has changed the way we socialize, but not why. If anything, The Age of the Internet has magnified the foibles and follies of those who careen around our social spheres. Earlier this month, an acquaintance tweeted his denouncement of fashion labels, the accumulation of “things,” and the disposable detritus of the modern world. He declared his need for a simpler life: one of value rather than of valuables – a life where intimates are to be trusted, adored and loved rather than feared, revered or used. This smart and passionate fellow, whose tweets and Facebook postings detail parties and photos of himself in fine-tailored clothes (which fit him exceptionally well) alongside celebrities, declared a spiritual goal. I can’t help but think Ms. Wharton would have seen irony in this.

A quick rise to the top would suit Undine Spragg more than the necessity of having to work for what she wants (though it could be argued that the career she adopts is an education in the customs of the nation Wharton so adroitly analyzes.) I found myself muttering “Undine Spragg, how can you!” as her decisions grew increasingly sociopathic. Parallels in our culture of tweets and quick responses have me muttering the same thing but with an ironic roll of my eye as I imagine Edith Wharton may have done; the country of Wharton’s birth continues to immerse itself in the waters of privilege where Undine longed to bathe.

In mythology, the ondine (or undine) is a female water spirit which lacks a soul until she marries a mortal man and bears his child. Basically, these creatures spend a lot of time seducing men to get what they want. When Undine Spragg meets Ralph Marvell, she believes she will move quickly up the class ladders into a world of glittering privilege. She is a beautiful, seductive creature with little more than charm and looks to support her. Shallow and devious, Undine is the vehicle for Wharton’s indictment of American custom. Had Wharton been writing today, this novel’s depiction of its female lead might have drawn accusations of sexism, but Wharton is not concerned with political correctness. Undine is simply the fascinating conduit for a thesis more concerned with motivation than manners.

Quick rewards are the promise of lottery tickets, American Idol and television’s other elimination-based contests. “Reality” shows offer a keyhole into the world of the famous who seem both more and less like us: less because of their wealth and fame, more because of the endless string of banal problems which become tools to smash the idols we’ve created. Last week Justin Bieber became the subject of viral attacks after a childish comment in the guestbook at the Anne Frank House. The kid’s 19, for pete’s sake! If every foolish thing I’d ever done at 19 were under scrutiny, I’m not sure I would have grown up sane.

The parents of Wharton’s siren-like no-gooder fail her at every turn with their indulgence but who was she to begin with? Does Bieber share her bloodline of American superficiality or was he just thoughtless? Was he born selfish and nurtured into a life of self-aggrandizement, like Undine? Is he a hollow creature who thrives on the souls of his teenage fans or just a kid who hasn’t learned better? Frankly, I‘m thinking it’s the latter based only on a wish to think the best of humanity (thank you, Anne Frank.) Certainly those who sit in judgment would avoid the whirlpools of malevolence which swallow the rich and famous. We would do better. Be better. Live better if we had what they have. But Undine, even as she acquires them, continues on the path her upbringing reinforced: get what you want at all costs.

5th Avenue north, at 66th Street, NYC, 1900. Undine's longed-for stomping grounds about a decade before her arrival.

Wharton, brilliantly, plays on our conflicting and simultaneous attitudes: Get it! Be it! Want it! But destroy those who don’t have it. We watch the rise of Justin Bieber, Lindsay Lohan, Amy Winehouse, Courtney Love, Whitney Houston, then revel as their stars plummet. The tide of celebrity culture brings them to the shore then sweeps them away. Undine, in Wharton’s novel, is a compelling if unlikeable character – the anti-hero who has become so popular in the last decade of television programming. If U.S. succeeds, she will not deserve it as we would. As we follow her exploits, we want simultaneously to help her and teach her a lesson. If only she were a better person. If only she weren’t so horrible. If only U.S. weren’t so much like us.

There is an Undine Spragg in all of us and it is for this reason we want both to stifle and satisfy her. We do know her. She is the bastard child of the American dream.

Pingback: Weekend Bites: Graphic H.P. Lovecraft, Painting With Borges, Leah Umansky, and More | Vol. 1 Brooklyn

This may be petty, but that pic can’t be 5th avenue, looking north. Central Park is on the wrong side!

It’s not looking north, the picture is taken FROM the north. I believe the lack of the comma may have confused you. The comma has now been added.