In Part 1 of Young Adult, Quentin Rowan is kidnapped, maybe, from the artists’ colony Cummington Community of the Arts.

FROM THAT NIGHT on, the temperature of our tranquil world began to change, the cycle of swaying trees and humidity damped a bit. People were cautious at first, made their observations through drawn shades. By the end of the week, the directors, the artists, everyone had arrived at the same conclusion: Nancy had become Veronica. Terms like “nervous breakdown” and “psychosis” floated around.

Nancy, for her part, seemed immune to the stares when she passed. Her pre-teen look got more and more outlandish: denim shorts and barrettes and wild streaks of rouge. She kept the pigtails and thick eyeliner, but added checked dresses and prairie-style frocks, as she went about her daily business between her cabin and Frazier and afternoon light slid off her back like some popular boy’s glance.

My memories of the next few days are tangential, filled with gaps and silences. On the one hand it was evident now that Nancy was frightening our parents with her rejection of adulthood and its hopeless vacuum; on the other, we children were all quite used to it and some of us had even come to see it as “kind of awesome.”

Either way, I have trouble recalling anything from that week except for the edges of things: trees, clouds, darkened rooms, a child’s face laughing. Were Kenneth and Alice there with us or had the already turned away, seeking help for their mother, making plans?

The flow of time here feels so precarious I can almost put my hand through it. If there are traces of the Robinson kids that week, they are small enough to exist now only on the molecular level, stirring and swimming around my hippocampus. And what about Nancy herself?

~

Feeling it would be self-deluding to continue writing without more facts recently, I emailed my mother to ask what she remembered. Several days later she replied, “Both Carole Maso and I perceived that [Nancy] was fast unraveling… She was about to turn forty and was going around the artists’ colony dressed like a young girl and carrying flowers in her arms…”

“What happened next?” I typed, knowing quite well, but wanting outside perspective.

“Nancy started alarming people even more when she said the dishes weren’t being washed at 250 degrees.”

After that, something was always wrong. She stopped writing. She stopped going to her cabin. Having fallen into her character, there was no more need for Veronica on the page. She focused all her attention on day-to-day things like dishwashing temperatures and anxieties about Cummington’s general maintenance and safety. She’d scream or drone (either equally likely) about the power and water supply, health codes, repairs…. The directors tolerated these attacks with rolled eyes and bewilderment, until the day she finally scared everyone with her prediction that the Children’s Barn was going to burn.

She came into the big room at Vaughan during lunch and warned the directors about the charcoal fires. The pits used for barbecuing, she said, were going to start a fire where the children slept. I watched the whole stylized argument that followed, fascinated. When had Nancy become such a stickler for fire safety?

She was loud and raggedy and doll-like. Someone said, “I wouldn’t worry about it, Nancy.”

“Well I am worried. Very worried!”

I thought of Linda Blair once more. It was like an exorcism in reverse. Where love and dreams and other things of the spirit once passed the time together mindlessly, now fear had taken priority. I didn’t know then how easily it could enter a person and freeze them from the inside.

Someone else said, “There’s never been a problem before. They’ve been there for years and…”

“I’m telling you, all it would take is one little fire. Someone could come along in the night…”

“But who on earth would do that?”

“The slightest wind… just the slightest little wind and… ”

Some of the younger kids were crying. I could see my mother and the other parents conferring in whispers. Something like, how after the rest of her behavior, prancing around as Veronica and so on, this was really too much. Then, looking back up and into the smudged make-up around her eyes, something else became clear.

“But Nancy,” someone said. “We haven’t barbecued all summer.”

“No,” said Nancy with her flowers and her dress and permanently- blushing cheeks, “But we might. Someone might.”

Everyone shivered a bit, realizing collectively: Nancy was going to burn down the Children’s Barn.

My mother writes, “That night, I removed you to my studio, called ‘The Den,’ which was across the street and through some fields. I felt you would be safe there.”

~

Dawn had begun to reveal itself now, the deepest, most innocent time of day, I felt I could almost hold it inside my hand, as we moved through one dream to the next. Kenneth was pushing aside the branch of a shabby bush for me to pass, and Alice had already climbed over the grease-brown rocks. There was a stream up ahead, a stream I’d never seen, though I had often heard its gurgly dispatches through the long afternoons, and knew it was called The Rivulet after a poem by William Cullen Bryant.

We continued along our green pathway, Alice in the lead now, with the sky glowing purple overhead. I thought of Sam Gribley from My Side of the Mountain. And though he had forty dollars, a pen knife, and flints to make fire with when he set out on his journey, still I hoped this was all leading to my own escape into the forest. That the paths might dissolve behind me and, like Sam, I could rule my own kingdom until I was old and restless.

We had passed the Rivulet and entered the unbroken realm beyond the trail. The way was clear, lit with a frail light from the hollow. We were very close. Moving slowly. My cheek brushed Alice’s shoulder sleepily. Kenneth took my arm, shaking a little in the fresh wind, and pointed out a rutted tree stump rising from the broad path. He told me that was the place where William Cullen Bryant had conceived his poem “Thanatopsis” while still a teenager.

An assemblage of the Greek words “Thanatos” and “Opsis,” death and sight, the poem, in a tantalizingly jingle-jangle fashion, tells us that nature can lighten our fear of death. Walk out into the evening, young Cullen Bryant says, or through some autumn brambles, and listen for nature’s voice. Perhaps it’s dawn, after a rainy interdiction, the world is blooming. Pure. When it speaks, you catch glimpses of things you’ve never seen, a new freshness, flower life without name. The edges of the scene glimmer as you wait, and finally it says, in a voice you feel in your shoulders that when you die you won’t be alone, you will be mixed back into the earth, the night lawns, Thanatos’ realm, where everyone who has ever lived already resides. Not in terror, but in gypsy-like celebration.

Finally I turned to Kenneth and asked him if this was why they’d brought me out here, to this odd stump where the great man sat. He shook his head with laughter, and Alice said our final destination was over the next hill, that this was a place where people like us could call out to each other in the future, across the pathways of our dreams.

~

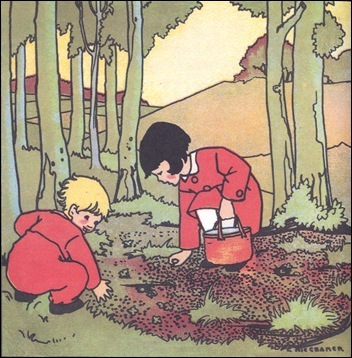

As if to reveal the truth, Kenneth pointed to the underside of the hill to a sudden burst of raspberry bushes. They lit the valley in clusters of fire-bloom. It was just after the morning dew, and even the woody stems glimmered with thick light from the fruit.

“This is the best time to pick them,” Alice said.

She reached into her bag and pulled out a little tin pail for me. Kenneth already had his and watched me with a smile as he passed, somewhat ceremonially, into the bushes. Alice made her own entrance, hushed, into the top-heavy labyrinth, and soon her pail, all our pails, were filling up with the little rosy berries. I grew caught up in the feel of their ruby skins.

All I could see were the berries and nothing else around. It shifted my sense of perspective, until I couldn’t be sure whether it was us who’d brought the raspberry chamber into existence, or the labyrinth itself that had led us there, Theseus-style, simply to show us there were places in the world so beautiful they flared with a kind of uncontainable light that was perhaps only an intermediary between us and something better.

Soon our pails were full, and the day was deepening. Alice spoke but her words and their meaning diverged. “The light is coming,” she said. It was a prosaic statement, but we heard in it a halo of the notes no one else could.

“We should get back before breakfast. Your mother would be mad if she found out we took you.”

~

On the way back Kenneth and Alice were quiet. I followed them smiling, and considered all the ways I could brag about our trip to the other kids. Before I’d even finished the thought, Alice warned me against it. If the others found out, the berries would be gone by the end of summer. They would have to find the patch for themselves.

Kenneth could see me frowning and joked, saying, “Now that Quentin knows it may be gone by then anyway.”

The truth was, I’d been eating raspberries the whole way back, and my face was purple from the juice.

“You’ll have to wash it off,” Alice said, “before we get back.”

I thought of Huck the Red-Handed stuck in town with the Widow Douglas and all her servants to keep him, “Clean and neat, combed and brushed, and they bedded him nightly in unsympathetic sheets that had not one little spot or stain which he could press to his heart and know for a friend.”

I crossed between the trail and the stream and found I was crying. I wanted a spot. A mark, a memory. A friend. Something to prove it had happened and the moment wasn’t just some story I’d read. Kenneth and Alice had cared enough to choose me and no one else. To keep the raspberries a secret and stay out of trouble, however I’d have to wash the red from my face.

I could hear Alice’s footsteps behind me. Then her hand was on my back and her face next to mine in the water. Crackling, I remember thinking it was crackling, as it slid over the little rocks and minnows.

“It’s not so bad,” she whispered.

I shook my head, but said nothing.

“Really, it’s not. Now you know where it is. Now you can go back whenever you like.”

I could feel the chilly water slide from my face as I nodded.

~

By the time we made it back to Cummington I was exhausted. I walked between the siblings, each one holding my hand, back to the gray rooms. Kenneth and Alice helped me creep back into the legs of my pajamas and then into bed, as the last of the night’s dreamers found those unseen truths vanishing, gliding away from them, rounding the edges of something solid and unbroken.

Alice kissed me on the cheek, then Kenneth ruffled my hair. I remember how tired his eyes looked, how red the irises were.