THE SECOND THE words left my mouth, I felt like an asshole.

“Have cops ever harassed you under the Stop and Frisk law?” I asked my friend Luis over Thai food in New York’s Chelsea neighborhood last spring.

I was in town on business and to see friends and aside from the punitive humidity, this had been another glorious trip to my favorite city. I adore Luis and admire his art and during what turned into a five-hour dinner, we discussed everything from his upcoming documentary and my upcoming book to our respective loved ones who died young and suddenly. And because each of us is socially progressive and politically active, we mulled the latest news, as we often did together online. So my Stop and Frisk question arose as an organic part of our conversation. I.e. it wasn’t a non-sequitur, like asking him if he’d eaten bacon on the moon.

But still.

I’m white. Female and disabled–so I’m not holding all the cards–but white nonetheless. Was it obnoxious to ask my African-American and Latin-American friend if he’d been stopped by NYPD because of the color of his skin and his gender?

It didn’t seem to be. Luis said he’d never faced Stop and Frisk firsthand, but had seen it in action and explained that witnesses often shot video of the cops, both to let them know they were being watched and to try and stop potential atrocity. Like all my friends of color, he relayed a story of police questioning him for no reason–in his case for switching subway cars–and I told him how my mom was instrumental in getting four racist detectives fired when she was a deputy prosecuting attorney. (Please note none of us is anti-cop; we are all anti-police brutality.)

Luis and I kept imbibing large quantities of noodles and our talk flowed to myriad other topics. At the end of the night, he helped me catch a taxi, saying, “Experiment! Let’s see if a Black man can get a cab in New York.” I laughed and said, “Let’s double down. I’ll stand next to you and we’ll see if they’ll stop for a Black man and a cripple.” Last week he congratulated me on my recent engagement and this morning I wished him happy birthday for his nephew. Luis reached out to me when I was grief-stricken many years ago and a deeply kind, funny and trusting friendship arose.

So why does my question still bother me?

It’s not because of standard issue white liberal guilt. (I’m prone to guilt, but its origins are personal. See: “Oldest Child” and “Good Greek Girl”.) No, my question bothers me because it was inconsiderate and possibly intrusive. I didn’t regard that if Luis had been subject to Stop and Frisk, he also would have been subject to a type of degradation that as a white person, I can never really know. And then he would have been delving into pain when he’d probably rather enjoy his pad thai.

So why did I ask him about his experience with Stop and Frisk in the first place?

Because I can and do read first person stories by writers of varying races, creeds, ethnicities, genders and sexual orientations. But as any sentient being knows, reading is not the same as listening. And listening to each other’s stories is, in some ways, what defines us as humans. Maybe more importantly, it’s how how we learn what’s really occurring in each other’s lives. Our possibilities are almost boundless, but as a result, sometimes we fail to empathize, because there are so many shoes in which to walk that proverbial mile. And history shows our failure to empathize leads to the destruction of each other in both tiny and horrific ways.

The truth, of course, is that I’m usually in pain, my balance is faltering and my legs are numb. And that’s on days I’m well enough to run said errands. When I’m dressed up and out of the house, I enjoy forgetting about my health to the degree I’m able. Small things like browsing the local bookstore can be an adventure and I’m giddy on the days I can venture to a few different locales in row.

In the years after I first became ill, such questions bugged the hell out of me. Crutches and canes are nifty ice-breakers? Really? I liken the adjustment to new illness to viewing one’s previous and healthy life through a membrane: it’s achingly close, but you’ll never touch it again. It’s emotionally devastating and logistically confounding. It takes years to accept your body’s new parameters. In the meantime, having the produce guy at the Farmer’s Market laugh and yell, “You must be a clumsy one!” doesn’t help so much.

But as noted, I’m 23 years in. I’ve spent most of my adult life answering questions about my illness and similar ones and my physicians say I’m the best informed layperson they’ve met. In brief encounters, I politely smile and say, “It’s a long story.” If someone is genuinely interested and considerate, I share pertinent details and often a person thanks me and tells a story of his or her own health tripwire or that of a loved one. There’s a surprising degree of connection and intimacy at times, a recognition each of us is subject to our bodies and to forces beyond our control. In the least cheesy way, we learn a more about what it’s like to be the other person.

I was ignorant of my mistake until a commenter corrected me. And I was glad for the correction because I didn’t know I’d screwed up. I certainly didn’t want to cause anyone pain.

It was the way the commenter corrected me, though, that got on my nerves. My piece was unambiguously pro-LGBTQ. I’ve been volunteering or writing letters on behalf LGBTQ persons my entire adult life and I have a boatload of loved ones, colleagues and neighbors who self-identify as one or more of the above. Correcting me was warranted; going off on me was not. All I could think was, “I’m genuinely sorry, but Internet stranger, you need to learn who your allies are. And then maybe cut them a little slack.”

I rattled off a list of Southern politicians hellbent on reviving the Confederacy and colonizing women’s reproductive parts. He patiently agreed, then pointed out not all Southerners had voted them in. He discussed the times he’d been initially dismissed when people heard his slight Southern accent. He helped me realize that if a person so massively intelligent could be wrongly judged based on the faintest hint of a regional inflection, I was helping perpetuate one stereotype while trying to dismantle others.

Because he was so forthright in sharing his experience, I haven’t made jokes about the South since then. Plus, he’s a really great kisser. But it’s mostly the forthright part that swayed me.

I’ve been on both sides. While not for a second ignoring my white privilege, I do know what it’s like to singled out for a perceived deficiency. It can be isolating and heartbreaking. It’s in no way the same as centuries of institutionalized dehumanization and violence or wrongly being categorized as mentally ill or correcting the pervasive notion one is a redneck with a mouthful of chaw.

But I know from my missteps and mistakes that I’ve learned the most when the person I accidentally hurt explained to me why I’d hurt them. And I know how hard it is to do this patiently because, as noted, I’ve been explaining my own illness and a number of others for over two decades. Sometimes the questions are so inane, I want to bite on a leather strap to keep from asking, “You’re kidding me with this, right?” I want to further understanding of what it’s like to have a degenerative illness, though, so I breathe and proceed.

And I still don’t know how much we need to teach our allies and how much they need to learn for themselves.

But I do know we need to recognize when someone is on our side. And that if someone is fighting the good fight, a patient explanation teaches them far more than a brisk dismissal.

I know I’ve been wrong before, but I’m forever grateful to those who have helped me get it right.

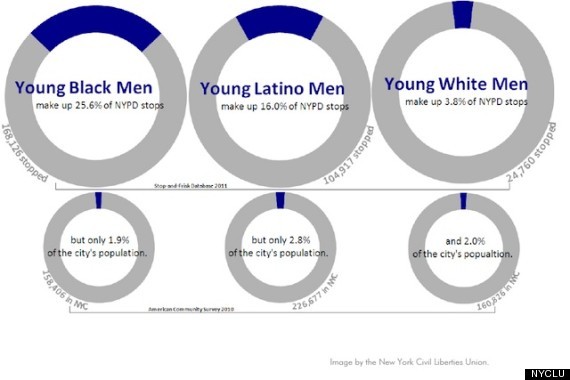

I agree with everything you’ve written, Litsa, but I have to note that every the “most favored” group, young white men, are stopped at twice their proportion of the population.