KERSTVLOED

Ruud Langbroek

Groningen, December 25, 1717

The water is icy, cold dark swirls that I tread with my hands and feet as best I am able, but swift currents tug in all directions, and more than once I am hauled downwards. My extremities begin to grow numb.

The sky is black with thunderclouds, the driving rain mixed with shards of ice. I’ve no need to inspect the seawall to know that the dikes have breached, that the town is underwater. Waves and rooftops, stripped twisted trees and collapsing spires, submerged in the flood. Domesticated animals, dogs and sheep, whimpering and bleating. All around I see terrified eyes- of drowning horses struggling to keep their heads above water, wild, whinnying in fright; and of people I know from town. Marysa De Cloet the tailor’s wife and Gerritt Janssens the miller are swept out of sight. Others clutch at tabletops and sideboards, looking almost comical, bewitched, flying through the air on dining sets past the roofs of houses. Chattels on the waves- chests and wardrobes, chairs and clocks and brooms. Carts and wagons upturned, spoked wheels spinning in the current. A crush of oxen, splashing and lowing.

A southwesterly storm battered the coast for days, and on Christmas Eve it shifted to the northwest, bringing with it a hurricane gale. A surge of water breached the dikes and the lowland beyond the seawall flooded. The villages of Egmond, Wangerooge, and Juist were swept into the sea. Groningen and Friesland were flooded. Inland, the banks of the Ems and Elbe overflowed.

I had gone to bed early.

The sea came into my room and I was swept out the window on a wave.

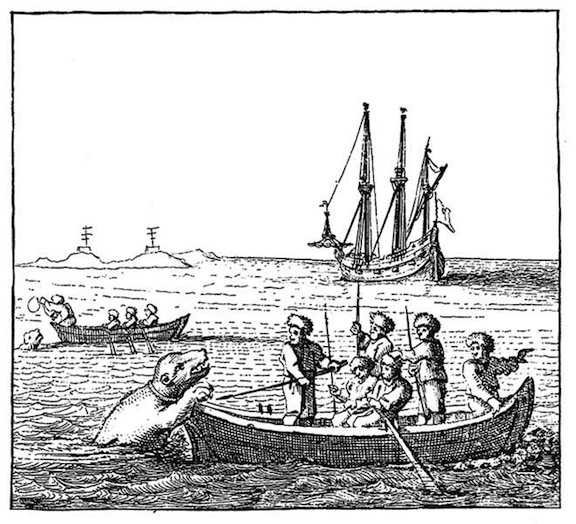

Barques and galleons from the harbor- unharmed by the collapse of the dikes- have begun to move cautiously inland, sending out men in launches to navigate the narrow ways between buildings. The drowning townspeople cry out to them- skin deathly pale, draggled hair frozen- splashing their arms and pleading for mercy. The men start pulling people out of the water and throwing ropes to those who have climbed up on the roofs. One of the galleons gets too close to the houses and collides with a crushing sound, tearing away tiles and scattering them to the flood.

Some of the men in the launches start hauling in barrels of brandy and other valuables instead of people, looting the flotsam. They fend off the desperate drowning with pikes. A woman drifting towards them with her arms out in supplication is tugged beneath the surface and vanishes.

The cold gets the best of me and my consciousness dims. I am next aware of being lashed by branches stripped bare by the force of the water, tangling around my legs as I am drawn by the current through the treetops of an orchard. All around me are apples bobbing on the flood . . . an enormous black mare swirls close by and I am almost struck by its hooves as it kicks against the current . . . the man in the last tree reaches out for me as I float past, but our fingers sweep across each other. The current takes me. I am swept past a house that has floated up off its foundations whole. In the attic three small children with terrified eyes stare from a mullioned window. The house turns in the current and the children are lost from view.

I am borne away, out past the dikes, round the isthmus, out to sea.

Slowly the rains relent and the sky darkens to near blackness. Up ahead it seems the storm clouds part, as if a curtain has been drawn back, and the clear night sky is revealed, pitch velvet, from which shimmering stars- first one then another- wink on like will-o-the wisp. Shining out brightest is Stella Maris, in her long white robe and silver cloak of stars, standing astride the waves, reaching out her hand to me . . .

I cease to struggle against the current, allow myself to slip beneath the dark surface, feel my body go limp as the water wells over my head. The sound of the crashing waves and the howling gale- all the tumult recedes- the whinnying of the horses and the barking of the dogs and the pleas for God’s mercy in the throats of the doomed. Underwater I see shadows of men and horses kicking their legs as I settle down into darkness. The sins I committed in life play out before my eyes: wrath, greed, sloth, pride, lust, envy, gluttony. I feel them washing away from me, as if they had never really been mine at all. The man I had been unravels, and I drift naked into death, new and uncorrupted. As my body sinks down into the darkness, my soul drifts up into the starry night sky.

I am saved.

BLINDED

John IV Laskaris

Byzantium, 1302

I remember hunting with falcons. My superhumeral was made from cloth of gold, richly embroidered and studded with gems. I wore shoes of gilded leather and my chlamys was of patterned silk. I was clever at chess. I loved the cold feel of the carved pieces, surrogates that on a whim could be sent to victory or to death. I played for hours on the sun terrace at the palace with the regent, Mouzalon.

I was to inherit the empire of Nicaea.

My name is John, which was my father’s name.

I can hear the semantron ringing Vespers in the refectory, and make my way from my cell to the chapel. I know the way by feel and by the number of steps, and I count the hallways that open out on either side as I pass. I have adjusted to my circumstances well enough, although I must occasionally ask God for patience. The monks are chanting the hymn as I enter the hall. The air is thick with incense smoke from swinging censers. I kneel briefly and take my place on a carved wooden bench.

I’d had a religious upbringing. My father felt that I should be at least as well educated in matters of the spirit as in matters of war. I was spellbound by the golden faces of the saints in the chapels, the illuminated manuscripts, the dramatic tapestries and mosaics, the icons of Jesus and the Virgin Mary and Saint John the Baptist, but I was most fascinated with the archangel Gabriel.

He had wings, and yet he seemed so sad. I could not imagine being sad if one had wings, if one could take to the sky whenever the whim came.

I vowed that when I was Emperor I would have a set of gilded wings made.

My beard is quite long now. My vestments are woven of coarse cloth. I travel the countryside on a donkey. I divide my time between religious services, private devotions, and what work I am suited for. My days are measured by the ringing of the semantron.

Not long after my father’s death, my protector George Mouzalon was murdered. The usurper Michael Palaiologos named himself regent and took troops to battle the Persians for control of the lost capital of Constantinople. He won, and when he rode back into Nicaea he crowned himself Michael VIII of Byzantium, Emperor.

I was taken on my eleventh birthday. They held me down and carved the eyes from my head.

That was Christmas Day, 1261. In the monastery I wept blood for days. The monks feared I might weep my life out, but I survived.

In the evening after Vespers I am summoned to the bishop’s chamber, where I am informed that I am to receive an important guest the following morning. No less a personage than Andronikos II Palaiologos himself. The Emperor. Son of the man who had me blinded. He seeks an audience.

I spend the night in quiet contemplation, praying for the strength to suffer his scorn with benevolence. What else could he possibly want other than to see the enemy of his father humbled and debased?

In the morning he knocks at the door to my cell and I invite him in. I imagine how wretched I must appear to him in my rough vestments, my visage scarred, how superior he must feel, wearing fine clothes that are rightfully mine, ruling an empire that is rightfully mine. Would he gloat? I begin to kneel, but he won’t allow it, he catches my arm and stops me, forces me to remain standing, and although I can’t see him I can tell by the rustle of his chlamys . . . Andronikos II Palaiologos is now kneeling before me.

“I repudiate the actions of my father,” he says, “and I beg your forgiveness.”

I am stunned. This is the last thing I would ever have expected. “I repudiate the actions of my father,” ringing in my ears. “I beg your forgiveness.” I’m not sure how long I stand there.

At length I remember myself. I put my hand on his shoulder and I open my heart to him. I tell him how blindness has changed me for the better. How it has changed me not just physically, but spiritually. How it has spared me a life of sin and corruption. How it has shown me the way to salvation, purged me of worldly obsession, moved me so many steps closer to God.

“I have often wished I might have thanked the men who blinded me,” I tell the Emperor, “that I might have washed their feet and thanked them.”

I am fairly certain I hear him weep. We sit in silence together for a time, we pray together, he bids me farewell. I listen to him go- the closing of the cell door, the sound of footfalls in the courtyard. He rides off with his retinue.

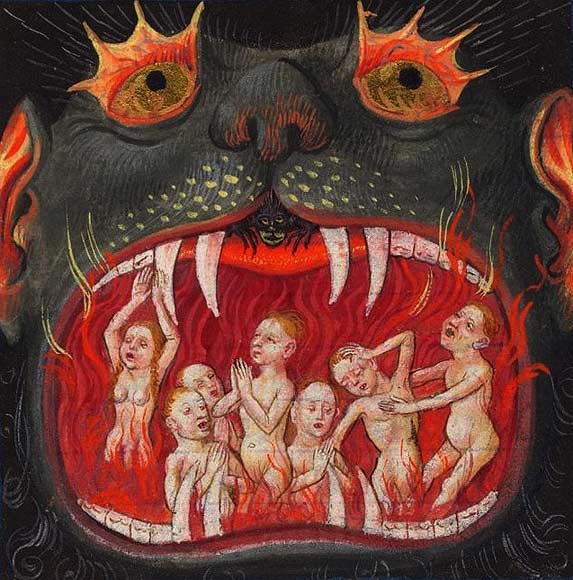

After he’s gone I fall to my knees and pray a most earnest prayer: that God in his great mercy might strike the man dead. That worms might eat his flesh. That he, and all his ancestors, and all his progeny might be exhibited on stakes. That they might weep piteously forever in the dim recesses of hell. That they might cry out through the flames and be unheard. That they might be boiled alive in cauldrons and tormented by demons. That they might be bound together on spits, over pits heaped with red coals, and burned forever. That they might be hung upside down and beheaded or buried up to their necks in blood and shit, that they might be broken on the wheel, that their tongues might be cut from their mouths, that their bellies might be split open and all their filthy progeny dragged from their wombs and slaughtered.

That through hell I might come riding on a great gilded chariot and roll across their scorched skulls, crushing them to dust.

I, John IV Laskaris, Emperor of Byzantium.

THE UNICORN AND THE LAMPREY

Germund Skov, Boatswain

Hudson Bay, 25 December, 1620

We sailed from Copenhagen on Whitsuntide in a pair of ships, The Unicorn and the Lamprey, charged by the king to discover the Northwest Passage to the Indies and Cathay, to locate the Anian Strait and skirt the Arctic Ocean, to find the legendary westerly route to the East. The captain was determined to cross Hudson Bay before winter, to avoid the fate to which befell Hudson himself: trapped in the bay by pack ice and unable to move his ship, his crew mutinied, setting him adrift in a dinghy.

The early voyage proved effortless, the weather fine. With the wind at our backs we made good time, out past the Faroe Islands, and then on to Iceland, and then on to Greenland and the Sea of Labrador. We entered the Davis Strait, crossed Frobisher Bay, and went round Resolution Island into Hudson Strait. Although still early in the season, we encountered occasional bergs of drift ice in the Strait, and the Bay was no better. Pack ice occasionally barred the way, and some of the men- Laurids Bergen and I, and some of the others- had to climb down ropes onto the ice with mattocks and axes, to cut a path for the ships to follow. It was down on the ice that we first encountered the white bear.

They were terrifying creatures to behold- tall as two men standing atop each other’s shoulders, with a powerful musculature, sharp claws, and fangs- we rightly feared them. We took to arming ourselves with spears when duty called us to the ice.

The white bear lived on a diet of ringed seals. They would ride the floes of drift ice out onto the open ocean, searching for prey. The seals hunted fish in the water below the ice, but they had to surface regularly to breathe. A bear would stand watch silently near a hole in the ice- waiting for a seal to surface- and when one did the bear would haul it out of the sea and tear it to shreds.

One day we were attacked by a bear as we hacked away at the ice. It rushed towards us at a surprising rate, and with a frightful roar set upon us. We stabbed it with our spears but would not easily die. We must have punctured the beast a dozen times before it fell. Then we dragged it back to the Lamprey and hauled it up over the side with hooks and winches. We gutted it on deck and skinned it.

Under the skin was a layer of fat four inches thick that we scraped off with knives and rendered in an iron pot. The bear yielded fifty pounds of melted fat for lamp oil. Then we hung the dense white pelt upon the mast to dry and measured it. It was fourteen feet from head to tail.

That evening we boiled the bear meat in a stew and the captain allowed everyone extra rations of ale and wine. It was a merry time. Some of the men cut chunks of flesh from the bear carcass and dared each other to eat it raw, like savages, and a game began. I myself ate one of the paws. The meat was greasy and coarse, with a briny sweetness. Inebriated, I fancied that the white bear was the spirit of Hudson Bay itself, and our triumph over it was an augury. We had beaten the bear just as we would beat the Bay. The men ate bear in a sort of symbolic triumph over the treacherous bay. The boatswain Laurids Bergen held the bear head aloft above his own and did an almost pagan dance, which was comical, until the captain advised him to stop.

Not long after eating the white bear, a majority of the crew fell ill.

Faced with the potential death of everyone on board, the captain reluctantly decided to return to civilization. But the pack ice had crowded in behind us by then and the way was now closed. It would be suicide to remain on the Bay with an enfeebled crew, and there was nothing for it but to overwinter in the southern extremity of the bay. At high tide we grounded the ships. We built lodgings on the mainland from felled trees. Many of the sick could not be moved, myself included. I remained aboard The Lamprey.

Our stores of salt fish and bread had been intended for a six month voyage. We had muskets, and some of the men were accomplished marksmen, and those who were still healthy enough went out to hunt. In the early winter they had a good time of it, game was plentiful. They hunted reindeer and grouse; they found nests full of eggs and wild cowberries. But when the first frost came, the game vanished. The huntsmen went further and further afield, only to return with less and less game. The salt fish ran out. Some of the men hunted rats in the belly of the ship. Many took fever and developed lesions and jaundiced skin. Their gums turned spongy, their teeth came loose.

As winter dragged on the men began dying. The mate Hans Brok died, and then Jens Helsing the boatswain, and then the lieutenant, Movritz Stygge. And then Laurids Bergen died, and the lieutenant’s boy Claus. And then Rasmus Jensen and Jens Borringholm and Hans Skudenes and Oluf Boye. Then the surgeon Kasper, and then Povel Pedersen, and then Jan Ollufsen and Ishmael Abrahamsen and Christen Gregersen.

On Christmas Day there would be a feast, the captain insisted. We may have been suffering afflictions innumerable- privation, illness and freezing cold- but we would still celebrate the birth of our Lord with a feast. The captain sent out hunters who managed to shoot several nice-sized grouse, and the cook made a miracle of those birds. The meal was delicious, although many of the men had trouble eating because of loose teeth. The captain tapped a cask of strong ale and he kept our glasses full through the night. The chaplain read the story of the nativity, and we sang hymns. It was a happy time, and although everyone became quite inebriated, no one quarreled, and we all enjoyed good cheer.

Once during the festivities I heard in the distance the roar of a lone white bear: a deep, victorious sound.

I lost two teeth during the meal, and later in the evening, I died.