IT PROBABLY SAYS SOMETHING about evolution that younger generations see the future as expansive, malleable and positive while the older generations eventually—and inexorably—see the past as safer, simpler and more sensible. Bob Dylan had it right, of course: the times they are a-changin’. But it wasn’t a ’60s thing: the times are always changing, it just depends on where you’re standing and what you expect (or want) to see.

And so: athletes were less corrupted, politicians more honest, employers more human. Take your pick and add to the list, because it applies to everything and goes on forever.

But in the early ‘80s it really was a period of transition, perhaps unlike anything we’ve ever seen. Way before the Internet, obviously, but even before cable TV was ubiquitous and the news was a half-hour show you watched after you woke up or before you went to bed.

Looked at in the necessary continuum of history, it’s easier to understand that the decade was simply straining toward the future, as we all do by virtue of being one second closer to death every time we exhale. And the ‘80s were faster and more—or less—complicated than the ‘70s, just as, in comparison, the ‘90s makes those years seem prehistoric. Example: at the dawn of 1980 nobody owned compact discs; by 1999 this revolutionary technology had already begun its death march.

Still, looking at where we are, now, and where we came from to get there, the ‘80s are somewhat suspended in time, a decade of transfiguration.

For me, nothing represents the shift quite like professional boxing. Baseball, football and basketball have not changed: they are still the biggest sports, only more so. But with MMA, ever-splintered affiliations and weight class rankings, DVD box sets and especially YouTube (like porn, people prefer violence when it’s cheap, readily available and as authentic as possible), the boxing game has changed. Few would argue it’s changed for the better or that it can ever be anything like what it used to be. Certainly this has something to do with the star quality (of which more shortly), but mostly it involves the logistics of entertainment, circa 1980-something. A title bout was an event that got hyped, shown on live TV and was then…gone (like virtually all forms of entertainment until cable TV and then VCRs came along to save—and immortalize—the day). Before ESPN, before everyone could record everything, you had to make time to witness an event, because the show would go on, with or without you.

This, perhaps more than any other factor, illustrates the once-insatiable appetite for pay-per-view events: they were events and you not only invested your money, but your time to be a part of it (at least as much as any witness can be said to be a part of any activity). It may seem quaint now, but the pay-per-view model revolutionized by the boxing promoters of this time is a microcosm of what the world would become; a blueprint for the business model that is no longer confined to sports. Consider reality television or even the music and, increasingly, book publishing industries, wherein a washed-up rock star or talk show host or someone with a Twitter account can decree who matters and, more importantly, why—and how—they should matter to millions of people. It’s equal parts hype, viral marketing and the machine of modern commerce: Everybody wants everything and whatever that thing is becomes the most important thing on the planet, at least while it’s being watched.

The 1980′s were, in short, the perfect time for immortals to roam our earth and ply a trade dating back to days when the loser became food for lions and being voted off the island meant public execution.

All of which brings us to Duran, Leonard, Hagler and Hearns. These men defined a decade and their fights function as Shakespearean works of that era: heroism, hubris, tragedy and, crucially, comedy—all delivered with lots of blood, ill-will and, considering what was at stake and how abundantly they rewarded us, honor. It was the neighborhood and schoolyard code writ large: the best fighters in any environment will inevitably find and confront each other. Before days when obscene dollars and unspeakable promoters did more to determine who fought whom for how much on what platform, these men sought one another to settle the simplest score: who was The Best and who could wear The Belt. Yes, there were malevolent forces, rapacious bean counters and outside-the-ring influences we can only guess about, but it’s neither wrong nor naïve to assert, unselfconsciously, that it was a more unsullied age.

Exhibit A, which can serve as the Alpha and Omega of my formative sports-loving life: For years, I regarded the Hagler/Hearns masterpiece the way oral poets would preserve the ancient stories: I remembered it, replayed it and above all, celebrated it. Put one way: I can remember everything about the circumstances of that fight (Monday night, 9th grade, watched it in living room with Pops, etc.). Put another way: still many years before YouTube I was in a bar with a bunch of buddies in Denver. We were busy telling old stories, catching up on new ones and drinking. All of a sudden one of us noticed that the TV above us was replaying The Fight. Immediately, and without a word, we all stopped whatever else we were doing and focused in on the magic, relishing every second. If that sounds sentimental, it is. It’s also something that could never happen today: in our mobile and connected world, circa 2015, this incident would be impossible to reproduce. And that’s the whole point. Sure, there is nostalgia involved (but let’s be clear: I would not change that world for a world where I can pull any of these fights up, for free, and watch virtually anywhere I happen to be), but more than that, this was an era where nobody who cared was unaffected and no one, looking back today, will trivialize. We saw the careers of Michael Jordan and Joe Montana and Wayne Gretzky, but those were extended marathons of magnificence, sporting miracles built like the pyramids: requiring time, sweat, blood and monomaniacal dedication. The great fights of the ‘80s were more like natural events, hurricanes that came, moving the earth and shifting the landscape, permanently.

***

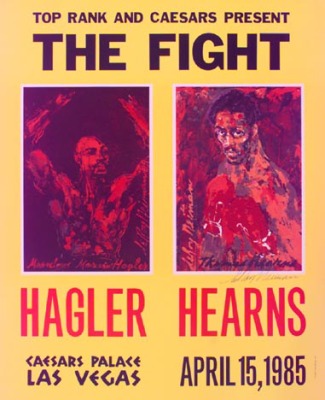

Let’s end the suspense and get this out of the way right up front: Hagler vs. Hearns on April 15, 1985 is the best sporting event I’ve ever witnessed.

First, some history: I’m not sure I thought so at the time; I had not seen enough yet. I’ve lived 30 years since then and savored lots of other great sports moments and the passage of three decades has only reaffirmed my verdict. Obviously I would never want to be put in the position of declaring what is the best sporting event (it’s not unlike “the best” anything: does that mean most enjoyable, most important, most influential, most popular, etc.?), but if I want to stand up and be counted, for my money and based on what I’ve beheld, nothing can possibly top The Fight.

(To be a bit more clear: I did not have any money riding, I did not necessarily prefer either fighter –though I did/do greatly respect both– and in many senses this was not close to the most personally satisfying sports moment. It was not Larry Bird in Game 6 of the ’86 finals, or Dennis Johnson shutting down Magic in ’84, or any number of moments from the Red Sox World Series of ’04 and ’07, or what the Redskins did to the Broncos during the 2nd quarter of the ’88 Super Bowl, or Riggo’s 4th and 1 run in ’83 vs. the Dolphins, or Dale Hunter’s 7th game series winning goal vs. the Flyers, or the glorious shock of Mike Tyson fumbling around for his mouthpiece after Buster Douglas beat his ass, or any number of sublime moments from the various NHL playoff series in the last two decades, particularly the beyond-epic series between the Stars and Avs and then Stars and Devils during the 2000 finals or…you get the picture.)

Secondly, some perspective: in other sports, championship moments are often (or at least all-too-often) lackluster affairs. Consider how many mediocre Super Bowls, World Series and NHL (even NBA) finals we’ve hyped up and been disappointed by. And that is just referring to the ones that are either blow-outs or the function of one team demonstrating their dominance on a day when everything falls perfectly into place. Those are understandable, even inevitable. But how many other times have we been let down by a World Cup final or a boxing match, because one or both parties tried to avoid the loss rather than secure (and/or earn) the win? I think of Brazil in the ’80s: those were the best teams and they probably should have won one or two World Cups (led by the incomparable playmaker named Socrates, but they could not restrain themselves and play it safe. Overwhelmed by their love of their game and their affinity for joga bonito, or allergic to the conservative style employed by the European powerhouses (like West Germany and Italy); they played with flair, audacity and because they could not help it, allowed a combination of chutzpah and zeal to expose their collective chins. My passion for the World Cup is hardly diminished, but I regret seeing teams play too-safe and sit on small leads, resulting in lackluster games on the biggest possible stage. It has only gotten worse in recent years, but it’s an undeniable recipe for success. As soon as Brazil reined in their aggressive and unbridled impulses they finally broke through, albeit it in joyless, aesthetically muted fashion. Their victories were, in many senses, objective fans’ loss: to finally win they had to play mostly sterile and boring soccer. As such I retain a fondness and appreciation for the ’82 and ’86 squads and care –and remember– very little about the ’02 team that won the prize.

The preceding paragraph might underscore why, in addition to loving the sheer entertainment spectacle The Fight provided, I appreciate and am humbled by the way Hearns and Hagler approached the biggest bout of their lives.

Am I supposed to do The Fight justice?

I will say, without too much irony, that in some ways I still feel slightly unworthy of what these two men gave us. I’m serious.

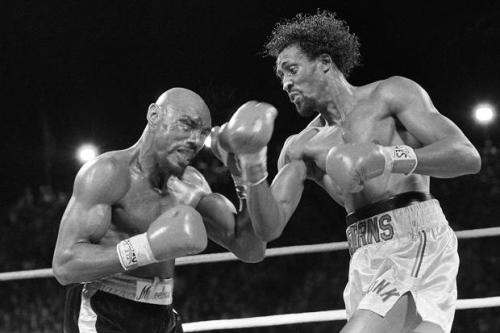

There is nothing in sports (is there anything in life?) that can match the three minutes of that first round. Not a second wasted, too many punches thrown to count, and a simple reality that transcends cliché: Hagler took Hearns’ best shot and stayed on his feet. There is much more involved, but it can really be boiled down to that simple fact. Hearns threw the same right hand that had devastated pretty much everyone upon whom it had ever landed flush; he threw that punch at least a few times and not only did Hagler absorb it, Hearns broke his hand on Hagler’s dome. At the same time, Hagler was inflicting unbelievable damage himself, and once Hearns’ fist, then feet, were shot, it was just a matter of time. It’s fair to suggest that Hearns made it through the next round and a half on instinct and courage alone. Hagler, for his part, used anger, resolve and willpower to, as he memorably put it, keep moving forward like Pac Man.

The second round allowed everyone, especially the viewers, to catch their breath. The gash that Hearns had opened up on Hagler’s forehead fortuitously ran down his nose, and not into his eyes (that could have changed the course of the fight), and when the ref sent Hagler to his corner (even though at this point Hagler had all the momentum) in the third round, it’s possible that this was what inspired—or scared—Hagler into deciding two things: The only person stopping this fight is me, and I need to stop it, now. There was simply no way he was going to let the fight get called on a dubious technicality, not after he had already taken the best Hearns could give him (and, it should be noted, for a man who was notoriously unlucky before and after this fight, it was almost miraculous that the blood didn’t gush into either of his eyes; that would have been an obvious game-changer, or worse, may have given the ref sufficient cause to end the bout). In that classic finish, an almost-out-on-his-feet Hearns jogs away from Hagler, turning to grin (as if to say “that didn’t hurt”) but Hagler is already upon him, literally leaping into the air to throw his right-handed coup de grâce. Down went Hearns, up went Hagler, and both men became immortal in that forever moment.

***

It was hard to begrudge Hagler, who’d never been a media darling and had been done wrong by several judges and promoters over the years. This fight was his vindication, and it was sweet (the sour taste in his mouth, that he still carries to this day, courtesy of the controversial ’87 fight with Leonard, remains an unfortunate footnote) while it lasted. I love Hagler for the guts, tenacity and resolve he displayed: he deserved to win. I admire Hearns for the respect he showed (to himself, the fans and the sport), willing to lose everything in an all-or-nothing strategy that would be unheard of, today. It was practically unheard of, then. More, he accepted the loss with grace and humor, and it remains moving to see the way he and Hagler embraced after it was over. The mutual respect the two men still have for one another is, understandably, unshaken.

What do we make of Hearns, who finished second in two of the best fights of the decade, both of which could easily be in the Top 10 (if not Top 5) of all time? In both instances, had he chosen to box instead of brawl he very likely could have won. He may still second-guess his strategy in the Leonard fight: if he’d been wise (or craven) enough to just dance away, he would have won handily on the scorecards. But he couldn’t; he just didn’t have it in him. I see this as neither cockiness nor recklessness; Hearns had a pride that was bigger than winning. I guarantee, despite his understandable regrets about being one of our most celebrated runners-up in sports history, he sleeps like a baby each night and is comfortable looking at himself in the mirror. He should be. In losing, especially the way he lost, Hearns is more inspiring than any number of athletes who own the hardware, claim the victory, and have done little if anything to make anyone emulate them. I’m not suggesting that a go-for-broke approach is advisable, in sports or life, and as The Gambler reminds us, you’ve got to know when to hold ‘em and know when to fold ‘em. On the other hand, when the light is shining brightest, or perhaps more importantly when no one else is looking, you have to be willing to put it on the line and achieve something you’ll be proud to remember.

Pingback: Murphy’s Laws: 53 Infallible Observations on the Occasion of Turning 53 | Murphy's Law