I

New York, June 17 – Charged with fortune telling and practicing medicine without a license, Herman Rucker, 39 years of age, known throughout Harlem as “Black Herman the powerful healer,” was held on $1,000 bail Sunday morning…. A lengthy complaint purports to tell “Black Herman’s” method of bringing back to a lonely wife the love of an unfaithful husband…. Bottles filled with strange liquids to be sprinkled in the four corners of the wife’s bedroom and on her bed, roots to be laid against the husband’s body, printed prayers to be slept upon…. During a visit on May 15, Policewoman Sweatman reports, 15 women and one man were awaiting an opportunity to confer with “Black Herman,” who finally came out of his office immaculately dressed in [a] Prince Albert coat, striped trousers and highly-polished shoes. On the walls and ceiling of a hallway outside his office it is alleged that “Black Herman” has painted “fantastic pictures of black devils, nude women, and a life-sized photograph of himself.”–“Harlem Healer Given Setback By Woman Cop,” Chicago Defender, 1927.

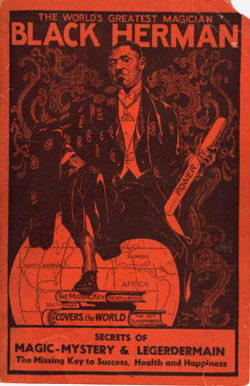

It was from mystics in India that Professor Black Herman, the “world’s greatest Negro magician,” learned how to resurrect someone who had been placed in a deathlike trance and buried for a week. A variation of this illusion would become his signature trick, and on at least one occasion allowed him to escape certain death. Legend has it Herman was in China when a secret syndicate of bandits, after hearing of his miraculous feats in Egypt and India, tried to enlist him in a plot to purloin a sacred diamond from the forehead of a statue of Buddha. “He refused immediately to have anything to do with the robbery,” Herman wrote in his autobiography, Secrets of Magic, Mystery, and Legerdemain (he refers to himself in third-person throughout the book), “for in all his life he has never used his powerful magic to rob or to commit crime.”[i] But he was now a liability; if word were to escape of the nefarious plot the bandits would surely be put to death.

Spirits supposedly alerted Herman that assassins had been sent to kill him, and, knowing well that running was futile, he decided it would be “easier” to commit suicide than be murdered. From “a little vial he drank poison from his own medicine cabinet,” and within minutes he was dead. Doctors were called in to confirm his fate. Throughout the town the sensational news spread. Herman lied in state for two days, before his body was sent back to Africa, where he could be buried in the Zulu village of his birth, the land of his ancestors.[ii]

Everyone in the village attended Herman’s funeral, including his mother and the King of Zulus. They all remembered the mysterious boy who had left long ago, taken by missionaries to America. A wise woman had once predicted the boy would someday become the world’s greatest magician. But now he was dead. The villagers were mourning and sharing stories when the casket lid was lifted from within, and out came Black Herman. The crowd fled in terror. Only his mother stayed. With tears coursing down her face, she embraced him. The villagers knew then that he was not a ghoul, but a man. They sheepishly returned, gathering around their long lost native son to hear his remarkable tales of sorcery and international adventure.[iii]

II

Miraculous origin stories are common among great magicians, and the above is part of Herman’s, as documented in his “autobiography.” Aside from his account, little is known of the magician’s early years. Even newspaper articles about the man cannot be trusted, for they often echoed Herman’s own tales, or recounted the testimonies of his patients, making the original story—the truth—nearly impossible to discern.

Though he claimed to have been from “the dark jungles of Africa,” Herman was actually born in Amherst, Virginia, in 1892, with the name Benjamin Rucker.[iv] As a teenager, he wrote, he endured a five-year period of hunger and wandering, during which he learned to speak the language of animals. (He was by all accounts an excellent animal impersonator and ventriloquist.) For several years he worked various odd jobs, living off a dollar a day. How did he survive on so little? “The answer,” he wrote, “is that Black Herman knows how to spend $1.00 twice and then have some change left.”[v] He wandered as far as Cincinnati, where he enrolled in a business course, before returning to Amherst to open a lunch counter. Though business was successful, he soon decided he wanted more from life.

According to his book, this is when Rucker set out alone on an extraordinary journey across the globe, during which he learned how to manipulate reality from the world’s greatest mystics and magicians. In Cairo he turned a scarf into a snake. In Paris, using supernatural intuition, he ascertained the whereabouts of a friend who had been kidnapped and tortured in order to discover Rucker’s secrets. In Africa, after his daring escape from the Chinese assassins, he defended his ancestral village against a marauding tribe by breathing fire, and on another occasion, saved a child who had been dragged into the thatches by a lion, using only a vial of acid and a dagger.

He was ready to begin his career in earnest. He returned to America.

Though Rucker didn’t mention it in his book, as a teenager he had apprenticed under a Virginia-based magician and patent medicine peddler named Prince Herman.[vi] The two toured the South together, performing sleight-of-hand, divining futures, selling lucky charms and healing elixirs. In 1909, when Prince Herman unexpectedly died, the 17-year-old Rucker assumed a new name—Black Herman—and carried on with the show, gradually incorporating more stage magic as he grew in skill and confidence.

It was a 1918 performance at a St. Louis carnival that first gained Black Herman national recognition. “Thousands of people, white and colored, came every day to the carnivals,” he wrote. “Bands of musicians, the merry-go-round, Hindu magicians, and Gypsy fortune tellers were there in royal splendor, but the star attraction—the beacon light of that carnival—was Professor BLACK HERMAN, the magician. He should say, as Julius Caesar had said, ‘VENI, VIDI, VICI.’ I came, I saw, I conquered.”[vii]

“I’m proud to introduce you to one of the greatest men of our time, the President of the Colored Magicians Association of America, and the undisputed monarch of race magicians,” announced the emcee. “All those present tonight are fortunate, because the territory he tours is so large that Black Herman only comes around once every seven years. You know the legend of High John the Conqueror, now meet the legendary Professor Black Herman!”

Herman had grown into a showman of the highest caliber. Tall, athletic, outfitted in an immaculately tailored tuxedo, he introduced himself to the crowd, and began telling stories of his Zulu upbringing. He mimicked the sounds of animals. He pulled rabbits and chickens out of the air. He turned water into wine, and oatmeal into coffee. He sawed a woman in half, and then put her back together. He let audience members tie him to a chair with rope, and using what he claimed were techniques Africans had used to elude slave traders, inexplicably escaped.[viii]

And for the finale he performed what is known as the Asrah Levitation. A woman is put into a trance, laid on a couch, draped in a sheet and, using only a magic wand, levitated 10 feet into the air. After passing a sword above and below to prove there were no strings, Herman would then pull away the sheet—she had vanished. The audience was thrilled. “Some said that he only showed that the hand was swifter than the eye,” Herman wrote. “Others said that he was a child of the devil, and had sold his soul to the devil, and thus had mastered the BLACK ART. One good Baptist sister said: ‘A man who can make a woman fly in mid-air is no devil or pupil of the devil, he be Elijah, the Second.’”[ix]

Prestidigitation was only part of Herman’s tremendous appeal. As religious studies scholar Yvonne P. Chireau wrote, Black Herman “reinterpreted the broader universe in which African American spiritual practices had been incubated, utilizing conjure healing, divination, and Hoodoo practices as part of his repertoire.”[x] He augured futures. He counseled audience members on personal issues. He sold various roots and herbs—the fundamental tools of hoodoo—that could be used to cast spells, undo jinxes, exact revenge, beat court cases, win the lotto, decipher dreams, and correspond with the dead. He even sold books that explained how to use the tools, and made himself personally available for rituals. He was simultaneously an illusionist, a life coach, a medical doctor, and a witch—a holistic healer occupying a place in African American culture that once belonged to the medicine man.

III

My pistol may snap, my mojo is frail

But I rub my root, my luck will never fail

When I rub my root, my John the Conquer root

Aww, you know there ain’t nothin’ she can do,

Lord, I rub my John the Conquer root

I was accused of murder in the first degree

The judge’s wife cried, “Let the man go free!”

I was rubbin’ my root, my John the Conquer root

Aww, you know there ain’t nothin’ she can do,

Lord, I rub my John the Conquer root

Oh, I can get in a game, don’t have a dime,

All I have to do is rub my root, I win every time

When I rub my root, my John the Conquer root

Aww, you know there ain’t nothin’ she can do,

Lord, I rub my John the Conquer root

—Willie Dixon, “My John the Conquer Root”

Hoodoo, like its more famous cousins Voodoo and Santeria, was born of West and Central African folk religions perverted by colonialism. All are testaments to slaves’ ingenuity in preserving their ancestral beliefs in extremely adverse circumstances. But there are significant differences between the three, which are largely the result of the varying circumstances in which Africans found themselves in the New World.

Africans brought to the Americas by the Spanish, French and Portuguese largely worked on immense plantations with minimal oversight. In many cases, families, sometimes even entire tribes, were left intact. So long as they pretended to convert to Catholicism, they were allowed to maintain their customs. And the faith to which they were forced to convert lent itself to syncretism; in the Catholic coterie of saints Africans perhaps saw parallels to their own native religion.

The reality that greeted Africans brought to the Protestant colonies in North America was radically different. Slaves lived in close contact with their oppressors. Families, tribes, language groups were split up as to avert insurrection, and following 1808, the importation of new slaves from Africa was outlawed, leading in a few generations to an entirely native-born population. Protestantism, with its strict interpretation of monotheism, was not easily melded with polytheistic animism, and in many cases, slave owners saw no need to convert their subjects, whom they believed to be less than human.

The sum result was the relatively swift dissolution of ancestral customs, and loss of cultural memory. Whereas Voodoo and Santeria continued to have a sophisticated theology and hierarchy of deities, slaves in America became Protestants, augmenting this new faith with old-time folk magic. Hoodoo—also known as conjure, or rootwork—is this magic. As Carolyn Morrow Long wrote of hoodoo in Spiritual Merchants: “There are no priests and priestesses; no community of believers; no ceremonies involving music and drumming, sacrificial offerings, and spirit possession. Personal misfortune is thought to result from the ill will of one’s fellow man, not from neglect of the deities, the saints, or the dead. Conjure is strictly pragmatic.”[xi]

“Historically, hoodoo has been distinguished from other forms of magic by its role as a tool of an oppressed race,” wrote Jeffrey Anderson in Conjure in African American Society. “Among the black populace, conjure was thought to be a source of protection against abuse by slave masters and unfair employers, economic success in a white-dominated business world, and hope to those charged with crimes under the Jim Crow justice system…. In short, conjurers were the poor man’s doctors, psychiatrists, and lawyers.”[xii]

The tools of hoodoo—herbs, roots, insects, bodily fluids, dirty clothing, sulfur, needles, dirt collected from crossroads or graveyards—could be found around the house and gathered from nature. Perhaps the most popular and versatile material is a root known as High John the Conqueror. It is not used medicinally; it is for luck. It may have been the root that gave Frederick Douglass the courage to fight his malicious master, and “rekindled in [his] breast the smoldering embers of liberty,” as Douglass wrote in his autobiography. John the Conqueror can be rubbed, kept on one’s person or in the home, boiled down into a household cleaner, or chewed and spit at those one wishes to influence. Also, perhaps due to the root’s resemblance to a testicle, it is often associated with virility and “frail mojos.”

“Since New World enslavement exacted a high price from both the slave’s physical body and his spiritual apparatus, ‘hope’ was indeed the tool that enabled the enslaved to salvage his own humanity,” wrote Katrina Hazzard-Donald in Mojo Workin’. “That vision of hope, resistance, rebellion, and triumph had no stronger expression in Hoodoo than in the sacred High John the Conquer myth.”[xiii] No one is sure if John the Conqueror was modeled after a real person. In most stories, he was an African prince sold into slavery, who relied on wit to undermine the authority of whites and maintain his pride. Hazzard-Donald argues that he is “perhaps the most widely known non-Abrahamic folk spiritual figure in the black Atlantic New World … not merely a hope bringer, he also was an intermediary between man and God, a warrior martyr, dying for ‘us,’ a soul saver, a sustainer, and a virtual saint of the old Hoodoo religion.”[xiv]

Perhaps just as important to hoodoo mythology was Moses, the emancipator of the Israelites. As Mitch Horowitz described in Occult America, Moses was “the great medicine man and conjurer of the ancient past—a savior from the African continent who used his divine powers to free and protect his flock. To hoodoo practitioners, Moses and Aaron’s spells against Pharaoh revealed the true purpose of Africa’s traditional esoteric crafts.”[xv]

Rootworkers had long held an affinity for the Old Testament. Perhaps they saw something of themselves in the Jewish tales of persecution and redemption. Cabbalism was particularly resonant with hoodoo practitioners; mystical texts such as Pow-Wows or the Long Lost Friend, and Egyptian Secrets of Albertus Magnus, first translated into English in 1855 and 1910, respectively, mixed the prosaic with the supernatural, offering folk cures for all manner of illness, including warts, toothaches, and fever, as well as rituals for good luck. But by far the most popular was The Sixth and Seventh Books of Moses, which Horowitz described as “the hoodoo bible.” First published in Germany in the late 18th century, and translated into English in 1880, the book was supposedly based on ancient Hebrew texts, and collects accounts of Moses’ spells against the Pharaoh, with instructions on the magical uses of the Old Testament’s Psalms.

Black Herman made stark the link between hoodoo and the Bible, speaking in a spiritual vernacular that appealed to blacks and whites alike. “When Moses was commanded by the Lord to deliver the Israelites from bondage,” he wrote, “did he not come in touch with magicians? Did not the good Lord use magicians to prove to Pharaoh that he was God and beside Him there was no other?”[xvi] Indeed, the Bible is filled with fantastic stories. What are we to call someone who turned water into wine, if not a magician? Did Joseph not regain his freedom through the interpretation of dreams? Did Jesus not give sight to the blind, feed multitudes with one fish and a loaf of bread, or resurrect Lazarus from the dead?

“In true hoodoo fashion,” wrote Horowitz, “Herman positioned himself in the footsteps of the great magician Moses—playing the part of a modern-day conjurer-emancipator.”[xvii] Black Herman’s stage act blurred the line between magic and miracle. During his performances, he would often plant an assistant in the crowd who would charge the stage, howling and writhing, enraptured in demonic possession. Herman, using an incanted prayer and a homemade elixir (which could be purchased after the show), drove the devil out, and pulled from the man’s chest a real live snake, which he hoisted above his head for all to see before letting it loose into the audience. What was a person raised to believe in angels and devils to make of such a “magic trick”?

IV

Finally, after having convinced the south and west that he was the greatest living Negro magician, and the equal to the Great Houdini, Herman decided to take New York City by storm. As he entertained in Detroit, Chicago, Cleveland, Cincinnati, Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, and other cities on the way, people said to him: “You cannot fool those New Yorkers. They will be able to penetrate into the mysteries and solve the Sphinx riddles, for they are ‘doubting Thomases’…. New Yorkers see all and know all. All the great preachers, orators, singers, musicians, elocutionists, entertainers and magicians come to New York. You can’t show them anything new. Better stay away from New York, or you will lose your money, damage your reputation, come to grief, and meet your Waterloo.” —Black Herman, Secrets of Magic, Mystery and Legerdemain[xviii]

In May 1923, Black Herman arrived in Harlem for a series of sold-out performances at Liberty Hall, the 4,000-seat convention center owned by the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA). It was a massive success, leading to a two-month residency that made him famous. His face was on adverts in the newspapers and on the back of buses. It seemed as if the entire city was talking about his newest trick, in which he resurrected a woman who had been buried.

Harlem was in the throes of a cultural renaissance, alight with new music and literature carried by the thousands of immigrants from the Caribbean, and African Americans from the South who were fed up with Jim Crow. The situation proved fecund for radical politics. “He moved into New York at a fortunate moment,” wrote the New York Amsterdam News in 1934. “Marcus Garvey, preaching the philosophy that a black skin was no handicap, found in Black Herman a dramatic argument to bolster his assertion.”[xix]

Garvey, the Jamaican-born intellectual who had sired the Back to Africa movement that would one day grow into Black Nationalism, founded the UNIA, and was responsible for booking Herman at Liberty Hall. Herman could be seen in Garvey’s massive Harlem parades, and it was said that he offered Garvey spiritual counsel. An article in the New York Amsterdam Times, dated May 30th, 1923, says Herman predicted that Garvey would be sent to jail on charges of fraud related to the shady bookkeeping and stock valuation of his Black Star Line shipping company. Herman’s prediction came to pass; Garvey went to prison that year.

In Harlem, Black Herman established himself as a pillar of the community. He befriended preachers, intellectuals and politicians, many of whom met at his home for a weekly study group. He was an Elk, a Freemason, and a Knight of Pythias. His books bore a commendation from Booker T. Washington. According to the Chicago Defender, between 1923 and 1926, he provided full-time employment to 20 people, and part-time work for 30.[xx] He made loans to locals and organizations, established scholarships, and performed for free to help churches pay their bills.

In addition to lucrative performances in big tents throughout the country, he purchased a printing plant, established a monthly magazine, founded Black Herman’s Mail Order Course of Graduated Lessons in the Art of Magic, acquired real estate, bought shares in two cotton plantations, gave personal consultations, and started herb and root gardens in a dozen cities. He became quite wealthy, and purchased a brownstone on West 119th St., which, according to Secrets, had “beautiful pictures painted on the walls and ceilings. A telephone … on every floor. A radio, piano, elegant rugs, and valuable antiques” and in the driveway, “a speedwagon, two Studebaker cars, and a roadster.” He continued: “Whenever he came into a town with his cars, assistants and $50,000 equipment, he came like a Prince. White and colored people would look around surprised to see a black man riding in such style and splendor.”[xxi] Not only did Herman bend the rules of physics with his sorcery, but he also transcended the suffocating racism of his time. What he was selling was the secret to good luck, and there was no greater advert than an ostentatious display of success.

His products, his performances, and his personal consultations were all perfectly integrated. During live shows, he hawked Black Herman’s Body Tonic, which was made with herbs from his own garden. Those who bought three bottles got a private consultation. By offering divination as a bonus, Herman shrewdly bypassed New York’s law against fortune telling for profit. He was, like all rootworkers, constantly on the edge of criminality. Beginning with the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, the federal government cracked down on unregulated products that made claims about having therapeutic value. Henceforth, conjurers had to be careful to describe their roots and herbs as having “alleged” capabilities to heal.

In 1927, Herman was arrested on charges of fortune telling and selling medicine without a license, the bane of all conjurers.[xxii] It was not his first run-in with the law; in 1923, he was arrested for assaulting a woman with the butt-end of a revolver.[xxiii] On this occasion, an undercover policewoman had visited his private office a number of times, complaining of abdominal pain and an unfaithful husband. Herman diagnosed her with appendicitis and prescribed Black Herman’s Body Tonic, with instructions to “rub with it.” To win back her husband’s love, he detailed an elaborate ritual involving scrapings from the soles of her feet and John the Conqueror root.

The trial, which the New York Amsterdam News described as “electrically charged,” was a disaster. Herman’s lawyer was nearly charged “with disorderly conduct for his temerity in questioning the sincerity and offending the dignity of the court.”[xxiv] On the day of sentencing, the lawyer showed up halfway through proceedings. On October 19, Herman was given a brief sentence in Sing Sing.[xxv] The papers called him a “quack” and “faker.” People joked that Black Herman came through every seven years because that’s when the statute of limitations on a crime expired.

But Herman maintained his innocence, claiming he was framed. “His enemies rejoiced thinking they had put an end to his activities,” he wrote, “but he did not stay in prison long before he was seen peacefully walking down the street. He was re-arrested seven times but each time he walked out of the jail. Iron bars could not hold him, so he was pardoned.”[xxvi]

While he was locked up, performers with names like the Original Black Herman, Black Herman, Jr., and Black Herman the Second toured the country, making good money on his fame. One New Jersey pretender was arrested after prescribing a remedy to a man suffering from rheumatism that involved a bag of salt, a gallon of apple vinegar, a yard of cheese cloth, and burying the afflicted leg up to the hip at dawn.[xxvii] Herman took the copycats in his stride, for they only enhanced his patina of mystery.

By 1933, when he premiered his ultimate illusion, he had figured out how to be in more than one place at a time without the help of imposters. A week before a scheduled performance, an audience was invited to a patch of ground named Black Herman’s Private Graveyard, where the great magician lay “dead” in a casket. For a dime, spectators could check his pulse. Then, they all watched as he was buried six feet into the earth in a grave guarded by Herman’s assistant. One week later, a crowd was re-assembled to see the casket get dug up, and Herman emerge alive and well, just as he had in Africa. He then led the people to the hall where he would perform that evening. The crowd was of course unaware that Herman had at some point during the burial ceremony escaped the casket, and headed off to the next town to set up the very same illusion. Live or dead, he had found a way to be everywhere at once.[xxviii]

V

Louisville, KY – A squadron of police were rushed to the J.B. Cooper mortuary this morning to prevent a near riot among women and girls who were trying to gain admittance to the funeral parlor to get a final look at Prof. “Black Herman,” noted magician and spiritualist. It is expected that 5,000 or more persons will file through the parlor to see the body before it is shipped to New York for internment. —“Black Herman, Noted Magician, Dies,” Chicago Defender, April 21, 1934

Legend has it Black Herman dropped dead on stage at the Palace Theatre, in Louisville, Kentucky.[xxix] That would have been a fitting end. According to contemporaneous reports, he actually died after dinner, from “acute indigestion.”[xxx] Curiously, in his final moments he rejected a herbal cure, and called for a doctor. But it was too late. He was 42.

Few believed the news. Spectators thronged the funeral parlor, so many that the police demanded the viewing be moved to the train station. People reportedly pricked Herman’s body with pins to see if he was alive. His assistant charged a dime for admission, saying, “It’s what he would have wanted.”

The funeral was held in New York on April 28th, 1934, and he was buried at Woodlawn Cemetery, in the Bronx. Hundreds attended the ceremony. “Some say it’s a trick,” the New York Amsterdam News reported. “They whispered about it at his funeral services at the Mother A. M. E. Zion Church. They said that the greatest Negro magician the ‘world has ever known’ would resurrect himself today. They are waiting ‘till sundown to hear that he’s done it.”[xxxi]

The people who had been fooled so many times by the “man who could fish doves out of air, the man who could decipher a message after you had burned it and sent him the ashes, the man who could cover a woman with a sheet and make her vanish” were not going to get fooled again.[xxxii] They had seen him buried before, often for a week or more, only to rise from the dead like Lazarus himself. They spent the night there in the cemetery, waiting. Some stayed a week before going home. No doubt a few of those suspicious souls, years later, went to see the Original Black Herman or Black Herman the Second when he came to town, holding in their hearts a glimmer of hope that maybe, somehow, the iron rules of the world could be bent, and a man could indeed return from the dead—if only he knew the trick.

[i] Black Herman, Secrets of Magic, Mystery, and Legerdemain, (New York: Empire, 1938), p. 13

[ii] Ibid., p. 14

[iii] Ibid., p. 15

[iv] Frank Cullen and Florence Hackerman, Vaudeville, Old and New: An Encyclopedia of Variety Performers in America, (London: Routledge, 2006), P. 114

[v] Herman, Secrets, p. 9

[vi] Cullen, Vaudeville, p. 114

[vii] Herman, Secrets, p. 24

[viii] Cullen, Vaudeville, p. 114

[ix] Herman, Secrets, p. 25

[x] Yvonne P. Chireau, “Black Herman’s African American Magical Synthesis,” Cabinet magazine, Issue 26, Summer 2007

[xi] Carolyn Morrow Long, Spiritual Merchants: Religion, Magic & Commerce, (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2001), p. 74

[xii] Jeffrey E. Anderson, Conjure in African American Society, (Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 2007), p. 152

[xiii] Katrina Hazzard-Donald, Mojo Workin’: The Old African American Hoodoo System, (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2012), p. 68

[xiv] Ibid., p. 71

[xv] Horowitz, Occult America, p. 124

[xvi] Ibid., p. 129

[xvii] Ibid., p. 128

[xviii] Herman, Secrets, p. 26

[xix] “Black Herman Regularly Raised ‘Dead’ But They Buried Him Like Any Mortal Man,” New York Amsterdam News, April 28,1934

[xx] “Black Herman, Noted Magician, Dies,” Chicago Defender, April 21, 1934

[xxi] Herman, Secrets, 27

[xxii] “’Black Herman’ in Toils of Law as Faker,” New York Amsterdam News, June 15, 1927,

[xxiii] “’Black Herman’ Again in Court,” New York Amsterdam News, August 15, 1923

[xxiv] “’Black Herman,’ Magician, Held for Trial in Special Sessions as ‘Quack,’” New York Amsterdam News, September 7, 1927

[xxv] “’Black Herman’ Given Sentence in Penitentiary,” New York Amsterdam News, October 19, 1927

[xxvi] Herman, Secrets, 19

[xxvii] “’Dr. Black Herman’ Gets 60 Days in Jail—Prescribed Weird Cure for New Jersey Man’s Rheumatism,” New York Amsterdam News, December 26, 1928

[xxviii] Cullen, Vaudeville, 115

[xxix] Chireau, “Black Herman’s African American Magical Synthesis”

[xxx] “Black Herman, Noted Magician, Dies,” Chicago Defender, April 21, 1934

[xxxi] “Black Herman Regularly Raised the ‘Dead’ But They Buried Him Like Any Mortal Man,” New York Amsterdam News, April 28, 1934,

[xxxii] Ibid

i need lotto number baba,ijebu lotto

Scholarly epistle. Would like to be on CCNY’s Harlem Renaissance Time travel program?

Pingback: clock parts

A really good movie. I’m not a karate fan, but it didn’t overdo it. It also got into the character. I too came here after googling the dedication at the end. This article was very interesting. I too have bought Meditations and also The Art Of War, after stumbling upon that searching for Meditations.This article only made it harder to understand what a producer really does. It’s chalk full of touchy-feely words like “inspiration,” “creativity,” “working with financiers,” “learning people’s work philosophies,” and tons of people loving everyone else’s “amazing talent and vision.” The closest it came to nailing anything down was a reference to “transpo and accounting.”Are producers afraid to concretely outline their roles on a movie for fear of sounding unimportant? Couldn’t someone say “I spent 50 percent of my time coordinating transportation, 25 percent working with the accountant on purchases and administrative work, and 25 percent of my time waiting to put out random fires as they arose”?