In Chapter 1, Nelly Reifler wrote of friendship and loss, fame, solid smoke and greyhounds, and seeing a friend, who becomes famous, start to fragment.

Chapter II concerned the aftermath of marriage and nearly boarding United Flight 93, a journey from Kansas City through dissolution and honeymoons.

Chapter III

1. That smell. Back in the city after two weeks at the farm, I couldn’t believe the smell. I don’t have to tell you what it was like outside the apartment, Dear Reader: it was New York City after September 11th. In Kansas City I had told a stranger, a taxi driver, that death was chasing me. Now the fact of death itself acted like a virus. I lay very still on the wooden floor. The ceiling spun. I couldn’t lift my head without vomiting. I vibrated with guilt and shame about Mahnaz, with stunned disbelief about Billy, and with a total conceptual breakdown about the fact that I was alive—rather than dead and in pieces in Somerset County, Pennsylvania. My brain hopped and buzzed. Was I alive, I wondered?

2. I still wonder. During good times I feel as if every day after those days has been a gift—I think, wow, because I was one phone call away from boarding United Flight 93, this is like extra life I get to live. But a lot of the time, it feels like I’m living in a kind of gray-scale world.

3. It was a good time to be traumatized in New York City. Nobody thought twice if they saw you weeping on a street corner or staggering, off-kilter, into a signpost. If you jumped out of your skin when somebody sat down next to you on the bus, or if you had a phobia about riding the subway, it was cool with the rest of New York.

4. I got weirder. After the acute phase, with the dizziness and the throwing up and the phobia about riding the subway, strange new facets of my personality began to emerge. I became reckless—when I say I wasn’t sure if I was really alive, I mean it—and I didn’t know how to behave as if I were going to continue living for a while. In some ways, this was exhilarating and freeing. I remember glancing out the window of my friend Elizabeth’s apartment and noticing that my car was gone. I shrugged and poured myself another glass of wine. It was just a car. I started driving drunk; it was fun to slalom down the streets of Brooklyn, drifting through yellow lights. I took up smoking again; it was as if I was on vacation in Paris and had to smoke and drink a lot of wine. I lost ten pounds. I had inexplicable bursts of passionate affection for people I barely knew or even strangers I saw on the street.

5. Noah returned to painting. His work grew more beautiful in leaps and bounds. It was another frigid winter in his unheated studio on a crumbling pier in Red Hook. There was no Fairway there, Dear Reader, no wine shops or bakeries. There was debris from a terrorist attack; there were gulls and roaming dogs. Noah would wear layers of sweaters, long johns. He had little care for his appearance or his physical well-being; his flesh cracked in the cold, and turpentine and oil paints—with their heavy metal pigments—seeped into the wounds. I didn’t visit his studio as often as I had before we were married, before the worst had happened. I didn’t feel invited. When he was home, he’d hunch over his food. He’d lie on the couch, staring at the ceiling, picking and scratching his skin and head. We had many fights about the speed at which he walked—I couldn’t keep up with him, and he said he was physically incapable of slowing down. I remember chasing after him in heels across Sixth Avenue in midtown at night with cars streaming by, horns honking, headlights flashing. He hurried, set on his path, head down, oblivious. Or hiding. Or daring the cars to hit him.

6. I couldn’t remember our wedding ceremony. It had been erased from my brain immediately after it happened. I was troubled by this total deletion. Looking at the pictures from the ceremony made it worse—there we were: two small, spiffy, momentarily happy people, vowing to spend the rest of our lives together, and I might as well have been looking at stock photos. I imagined that a shared memory of an oath-taking was intrinsic to the experience of a marriage that unrolled thereafter.

7. In the house where I live now you can watch the water meter. There’s a little black, triangular whirligig that spins when the water is running. When the water is flowing fast or more than one faucet is open, the whirligig spins quickly so it’s almost a blur. If there’s one tap trickling, the triangle spins slowly and you can see its points. When I picture my mind in this time period I’m talking about, it looks a little like the whirligig. In the days and weeks after my wedding, Billy’s murder, and September 11th, my mind spun so crazily it was a blur. It slowed down after that, but it was still spinning.

At a certain point, a new obsession came to consume me: making sure everything was right with me and everybody. In case they died or I died. This was easy with the people who were in my daily life. I had excuses to call my bosses every day, for instance, and my closest friends were doing a good job keeping tabs on me. But there were other people that were more of a challenge. Now that I was riding the subway again, how would I tell the F train conductor with the silky, lazy voice and the Chinese-Jamaican-sounding accent that I loved and appreciated him? Also on the F train, a junkie—probably coming from a methadone clinic—nodded out on me. I put my arm around her and held her close. She woke up when the train emerged into the light above 9th St, and she gazed into my eyes with great warmth and offered me a cookie, and I accepted it. A Russian construction worker fell asleep on me, too, and a woman about my age with a copy of the New Yorker on her lap. (I know: it’s odd that this happened so many times). I missed my stop in order to keep the experience going until they woke up.

I lost my filters, the way some people with head injuries do. I told people how I felt about them. I had a friend from graduate school, a fellow writer, now a colleague who was perpetually cynical and depressed and made jokes about suicide. Probably also bummed out by the fact that it felt as if the world were ending, he was in an especially antisocial phase, refusing to see most people, including me. What if he killed himself and never knew I cared about him? I called him one evening at the apartment he shared with his longtime girlfriend. Sobbing into the receiver, I told him I loved him. “Um,” he said, laughing nervously, “you’re making me really uncomfortable right now.” That friend is still alive, and is still—lucky me—my friend. But I think I didn’t tell the person that I loved the most; by this time, my love for Noah was too exacting.

8. I had seen her the morning of my wedding. As my mind spun during those months and then years, certain particular scenes and facts replayed themselves over and over. Mahnaz had dropped in on the way to the motel, the motel from which she would be traveling later, when the accident would happen. She embraced me and kissed me; it’s hard to describe what a warm, good-natured woman she was. It’s a custom in my stepmother’s culture for women to give each other jewels for major occasions, and she gave me a gold ring with four stones—ruby, emerald, diamond, and sapphire—and matching earrings for my wedding day. She was, in general, a gifted giver: I still have a silk nightie and robe, a robin’s-egg cashmere scarf, and a ropelike golden chain necklace from her—all birthday presents. A week after my wedding, when she was hooked up to the monitors and the machines that were keeping her breathing, keeping her nourished, I held her hand, and it was soft and warm and seemed alive. In my memory, she was in a dimly lit hospital room, with space only for the bed and the machines and one or two visitors sitting very close to her. My stepmother spoke soothingly to her sister in Urdu. The machines were unplugged a day or two after that.

9. And Billy. I hadn’t invited him to my wedding, out of respect to Dylan. But he had called me a few days before I went upstate to get married, to wish me the best. We had stayed close over the years, mostly because he was a great person and made sure we did. The night he was killed, he went out to see Hedwig and the Angry Inch with Dylan and Dylan’s new girlfriend, Ariana. Before he left his apartment, he had his first telephone conversation in a long time with Sarah, his ex-girlfriend, a writer with whom I’d had a tempestuous friendship. He told Sarah about my wedding, what he’d heard had happened to Mahnaz, how awful it was. I dreamed, not long after he died, that Billy was in a three-story house on a steep hill. The bottom floor was half-basement, but it had an entrance on the side that wasn’t embedded in the hill. The top floor also had a door that led out onto the top of the hill. But the middle floor had no doors to the outside. That’s where Billy was stuck, on a rocking chair, tangled in string.

10. Then, somehow, it was already early 2003. I was functioning, but I was not better. Noah was fed up with my tears and my weirdness, and he began to tell me to just get over it all. Each of the Bad Things had been a bad thing for him as well, but each was one degree closer to me than it was to him. One cloudless spring day, we were walking in Brooklyn, rounding a corner off a side-street spangled with bright new buds. I said something I’d said often before: I wanted to have another wedding ceremony, so I could remember saying some vows. I wanted to untangle our marriage from death and guilt and terrorism and murder, and Noah—exhausted, sick of the topic—said he didn’t want to because it would be a pain in the ass. I took this flippant comment like a stone into the pocket where I put the things he did that hurt my feelings, and I began to burnish it for later use.

11. Once, I was driving—sober—to work and talking to Noah on the cell phone. I was tearing up Eastern Parkway, past the Brooklyn Museum, through Crown Heights toward East New York. A construction zone seemed to pop up out of nowhere, day-glo pylons like a cartoon mirage. I swerved and the phone flew from my hand. I couldn’t pick it up. I just let it be. It didn’t occur to me that he might worry. The impact against the car’s floor had turned my phone off. Noah called and called and called—and reached my voicemail over and over again. When I got home from work that day, he seemed troubled. He asked me if I had checked my messages. “No,” I said. I never checked my messages. “You should really start checking your messages,” he said, and then buried himself back in a beautiful doodle, rubbing and picking the scalp behind his ear, the way he always did. Weeks later my mailbox filled, and I had to clear out the old messages. There they were: Noah’s messages from that day, Noah’s panicked voice; terrified that I had been in a wreck, telling me he loved me more than anything, that he couldn’t live without me. I hurried through the messages, moved and ashamed. But I couldn’t tell Noah that I had finally listened to them.

12. Dear reader, I don’t want to give you the impression that every moment of every day was dark. Noah and I still made each other laugh—he had a way of saying ‘gelato’ that sent me into hysterics, and if I said ‘delicious mushroom sauce’ in a funny voice, the same thing would happen to him. We still anthropomorphized the cats; we still cooked together; I still thought he was gorgeous and brilliant. In the mornings, we’d talk about what we had dreamt the night before. He bought me a beautiful red coat, which I still wear, for my birthday. There were times, when we were silent and still, that I could look into his eyes and believe that we were thinking the same thing.

13. Throughout all of this, news of Elliott trickled East. He was in terrible shape, I heard, worse than ever. I’d met his booking agent at a wedding, and we had become friendly. She hinted that Elliott’s life had turned grim, even while trying to put a bright spin on the situation. The stories that came across the hive were shocking. I was teaching at Sarah Lawrence at this point, and my young hipster students talked about Elliott Smith’s heroin habit, crack binges in the recording studio, and psychoses as if these things were theirs to talk about. When I’d speak with other old friends of Elliott, they’d say they were angry at him for losing touch, being distant. But I kept thinking of the time that he called me and left all of those messages, the time that he had tried and I had been absent. And when I was being totally truthful with myself, I’d admit that even if I had been in Brooklyn when he called, I would have offered some comfort, but I would probably have been too scared by his intense sadness and too selfishly wrapped up in my dramatic breakup to have really helped.

14. Haunted, I decided to say goodbye. Just in case.

15. Hoops. Autumn 1989. Nighttime. We put on our sneakers and head to the gym. The basketball court vibrates with fluorescent light, and the yellow wood floor glistens. It’s boys vs. girls: Elliott and Dylan will play against Melissa and me. We grab a ball and begin our match. None of us is very good. Elliott is fast. I can’t run or dribble, but I get an occasional basket. Dylan is sneaky and can pass well. Melissa has unbelievable, exuberant endurance. The game becomes livelier, rowdier. Melissa and I are having a grand time, chasing after the bouncing ball, letting it ricochet off the cinder block walls, popping it up in the air. Dylan’s annoyed, I can tell, and he’s trying to rein us in. But it takes a few minutes to notice that Elliott is getting angrier and angrier. Finally he gets the ball and slams it on the floor. He storms off the court. Melissa and I run after him. What’s wrong? we ask him. We’re winded, sweaty. “You’re not playing by the rules. You have to follow the rules.” He crouches against a pile of blue gym mats. We laugh. This makes him madder. This isn’t a serious game, we tell him. “We’re just throwing a ball around,” I say, lowering myself so I’m kneeling in front of him. “But that doesn’t count,” he says. I can see that he’s actually beginning to cry a little, he’s so frustrated. Melissa and I look at each other, baffled. We could tease him. We could goad him. But something stops us. Okay, we say, let’s go play a real game. Dylan and Elliott win. Elliott cheers up. And we’re happy because he’s happy.

16. A book was to be born. My collection of stories, See Through, was going to be published in September 2003. I had galleys. It was June, and Noah and I would soon be leaving for Europe to attend Dylan’s wedding. In 1996 I had read a story at the Cornelia Street Café and brought along a small pile of chapbooks that I was passively selling. Elliott was there, and he bought one. The title story, “Sloak,” was narrated by a serial killer who gives an infirm old veteran a blow job. The narrator describes the man’s penis in detail. (Later the story would be published in a small literary journal with so many typos it looked like it was written in some kind of Celtic dialect). Elliott had called me the next day and left me a message—did I never answer my phone?—saying he read the stories, and the writing was great, but they were so depressing he almost couldn’t take it. So I thought, now, in 2003, that he might like to see an entire book of my work. I felt shy for some reason. Nervous. I hadn’t seen him in years, and it was hard to reconcile the Elliott of my memories with the mythical beast spoken of by my students. The day before his Knitting Factory show, I dropped a galley off at Off Soho Suites, where he was staying. The next evening I was more nervous. I was on a mission to say the things you regret not saying to someone when they die. But at the same time, I hoped that my mission was a fool’s mission, and that Elliott was fine, the rumors were exaggerations. In fact, I hoped that my carrying out my mission, I might in some magical-thinking way prevent Elliott’s death. It made sense to me at the time.

17. The show was a train wreck. Elliott was in a stupor, and the crowd of fans seemed somehow gladiatorial, as if they wanted to see someone die—and they were practically seeing someone dying. Elliott forgot words to his songs, stopped playing, mumbled, made dark, self-damning remarks. Every time he fucked up, the crowd tittered; when he called himself an idiot they cheered. These fans: they seemed a different breed than from the old shows in the Nineties.

The Hipster Handbook had come out earlier that year. These kids were kind of like frat boys in trucker hats and skinny jeans. They had been, what, maybe ten years old when Roman Candle came out? How had this happened? I felt sick. Elliott brought a couple of young women out to sing wan backup on a song or two. I thought of how wry he’d been when I interrupted the intervention; this Elliott was not that Elliott, and the humor he was displaying onstage felt like a kind of act. He fucked up the song with the girls, and they looked anxious, and someone in the audience hooted. I left the room, went down the hall past the bar and out onto Leonard Street.

It was a sweet, soft June evening; smoking in bars had just been banned a few weeks earlier, and a few of the trucker-capped, skinny-jeansed young people were discovering what everybody would soon know: that the ban was actually kind of nice for smokers. It was an opportunity to get out of the crowd, clear your head, and flirt. I smoked a cigarette, too, and considered leaving. I could get Noah. We could go home, and Elliott would never miss me. I looked at the boys posing against the wall with their bony backs; I listened to their panicky, hormonal voices. I thought of Billy, tapping out a beat on a drum pad. I hadn’t had a chance to say goodbye to him. I thought of Mahnaz, and our hug the morning of the accident—and of holding her warm hand in the hospital. Had I used my ticket on Flight 93, how many people would have wished they could have said goodbye to me? Who would have regretted not telling me they cared for me?

I went back inside. The set was almost over. I found Noah. We made our way to the green room door. A gigantic bouncer blocked the way. He asked my name, I told him, and he slid through the door. Moments later he returned and informed me that I was not allowed to visit Elliott

I remember beginning to shake. Was it true that Elliott had decided to dump his old friends? Had I imagined, all those years, our good conversations? Then I reminded myself about the spectacle I’d just witnessed. Elliott was not in his right mind, and apparently the rumors whispered by mopey white undergrads were true. Then the door opened again, and a young woman was standing there. She was one of the singers who had been onstage with him. Pretty in an unremarkable way, wearing a T-shirt and jeans. She was smiling at me, reaching out her hand. She apologized. “I’m so sorry!” she said, “I’m Jennifer. Come in. I didn’t realize you were that author.” At first I didn’t know what she was talking about. And then—oh, yes—I was an author, sort of, almost. But what did that matter? If I hadn’t written a book, I wouldn’t have been allowed to see Elliott? And she was a gatekeeper, deciding who could greet Elliott? This was worse than if he’d simply not wanted to see me himself. Right then, I didn’t like her. She still refused to allow Noah entry.

18. Conversation #3. But I did what I’d intended to do. It was my third time visiting Elliott in this room, and the other two times seemed layered over this one like scrims. Nobody else was in there this time—maybe one other bouncer; I can’t be sure—but no friends, old or new. Just Jennifer, Elliott, and me. In Autumn DeWilde’s book of photos and interviews, Elliott Smith, a couple of people mention the hugs that Elliott gave. They were something to experience, it is true: totally enveloping, and, if you were five feet tall, a kind of carnival ride that lifted you off the ground. The hug I got in the green room reassured me that I had done the right thing. We sat down on that lumpy, low couch, and he took my hand. I complimented him on the show, and he brushed it off, of course. He was partly the same Elliott I had seen on stage—that is not Elliott—and partly the same as he’d ever been. Mostly he wanted to talk about my book. He had read a few stories before the show, and he still found them a bit dark, but was overflowing, in an almost embarrassing way, with compliments. He said he’d always wondered which one of his old friends would wind up becoming a successful artist. Painfully aware of the fact that my little book was a young writer’s uneven first collection that had been midwifed by a very patient editor, I tried to explain that I really was not a success.

Look at you, I said, you’re Elliott Smith. He shrugged and said that it didn’t count. In a sort of mumbling, rambling way he explained: he could never write a book, he said, because he wouldn’t be able to commit to that kind of unmediated transfer of his words to his audience. It was too intimate for him, the idea of one person sitting quietly and reading his words on a page. He said that he needed music, and an audience that he could respond to, who responded to him, whose personality he could sense, who encouraged him and was rooting for him. And who wants you to fucking die? I wanted to say. He went on; he got emotional. He did it all for them, he said, his fans were all he had left. His fans understood him, they were all that was keeping him going. Everybody else pretty much sucked, everybody else had betrayed him, old friends had turned against him.

Reader, I saw doom. I tried to move the conversation to specific old friends, people who cared about him, some who knew him better than I did, who wanted the best for him. I said that Alexander was doing well. Elliott snarled. “He’s married now, right?” he said, rolling his eyes. Yes, I said, and Christine’s great.” Elliott was unmoved. I tried filling him in on Dylan’s life, and Astrid’s. He lit up a little at the mention of Astrid’s name, but then collapsed again. I asked if he’d heard about Billy, that Billy had been murdered. Yeah…. He trailed off, he clearly didn’t care, he was getting nervous, he wanted or needed something. His eyes darted to Jennifer. She was getting nervous, too. Elliott, I said, I came here to tell you I love you, and I am glad you are alive. He stopped jittering for a moment. He looked surprised, abashed. “I love you, too,” he said. He gave me another hug. And I left, saying goodbye so quietly they couldn’t hear me.

19. From “All Things Must Pass,” Jonathan Valania, Magnet Magazine, January 2005:

Something terrible happened on the night of Oct. 21, 2003, in the cozy, box-like bungalow at 1857 1/2 Lemoyne Street in the Echo Park section of Los Angeles where Elliott Smith lived with girlfriend Jennifer Chiba. In Chiba’s version of events, the couple had an argument that grew so heated she locked herself in the bathroom. At some point, she heard Smith scream and unlocked the door to see him standing with his back to her. When he turned around, there was a knife sticking out of his chest and he was gasping for breath. Panicked, Chiba pulled the knife out of him, and Smith turned and took a few steps before collapsing. Chiba called 911, and an operator talked her through CPR until the paramedics arrived. Smith was rushed to a nearby hospital, where emergency surgery to repair the two stab wounds to the heart couldn’t save his life.

20. Dear reader, I tried writing this thing as a piece of semi-fiction. In the fictional story, I got hung up on the idea of magic cigarettes, though, which is typical of me:

After Steven’s show, I had ducked out into the summer night to smoke an unsatisfying licorice flavored herbal cigarette with Tony. The smoke was purplish gray and heavier than regular cigarette smoke. It lazed in a plane around our heads and then sank to the sidewalk. Tony said that if you bought the deluxe version of the cigarettes for a dollar extra, the smoke formed Sanskrit characters on its way down.

I stopped there. I couldn’t write the story of Steven Smith. I wanted to write about magic cigarettes. And the fact was that I was stuck with the facts, which involved somebody about whom three books have been written, as well as scores of articles, and countless blog posts and comments on blog posts, and so on, and so on.

21. Read Autumn DeWilde’s book for the interviews with Joanna Bolme and Sean Croghan, with Sam Coomes, with Ashley Welch—Elliott’s little sister—and especially for the short interview with Neil Gust. Imagine if you died, and a book of hundreds of photographs came out. Imagine it contained interviews with your friends and collaborators, never-sent postcards, even notes you’d made on ATM receipts.

22. Siva. A couch. A carpeted living room in a suburban Portland housing complex. Early afternoon. It’s 1991, and Elliott is glued to MTV. I’m sitting next to him. We’re eating sandwiches; we’ve got our feet up. Gish, The Smashing Pumpkins’ first LP, was released a couple of months ago. We’re waiting for the “Siva” video to come on; Elliott is obsessed. And then—here it is: oh, beautiful Billy Corgan and your noisy, insinuating guitar. Flickers of candles, the band playing their instruments, waxy-faced Corgan submerged. Yeah, it’s compelling, but I don’t quite get the intensity of Elliott’s reaction to the song. Explain to me, I say, tell me what you love. He says it’s not just the song; it’s not just the video. It’s the whole thing that the band is doing—the way they look, the way they play all of their songs. He cocks his head at Corgan: it’s how cool he is. I can see Elliott studying him—smiling, joyful, nodding his head to the music—and I’m filled with a kind of awe as I realize that I have one friend who is actually ambitious. While the rest of us drift away from college on our little rafts fashioned of Situationist theory, laze, and irony, Elliott knows what he wants to be when he grows up. It will take him a while, but he will get what he wants. And, when I figure out what I want to be when I grow up, remembering the electric, hungry look on Elliott’s face will help me get there.

23. I cried all the way home from the Knitting Factory. This time, unlike many times around that time, Noah understood why I was crying. We drove home in Noah’s Subaru, through the Battery Tunnel and up the Prospect Expressway to the little row house we’d bought a year earlier. We had a tiny backyard and a row of nine miniature apple trees. We hadn’t yet seen them bear fruit, but they would, and the squirrels would steal the apples before they ripened, then throw them on the ground. We didn’t listen to any music during that car ride, and we didn’t talk much. It was one of those rare moments when long-term monogamy makes perfect sense. There’s an argument for marriage somewhere in the concept of having a witness, a fellow keeper of accrued memories until one or the other of you goes the way of everything.

Holy mother of all that is holy. I, too, am known as a good hugger. I feel like I need to give you one after reading this! It was beautiful and harrowing and gorgeous and raw and brave and breathtaking and sad and sorrowful and almost happy and so Elliott and perfect.

I’m glad YOU are alive and were able to pry this out of your soul. I’m sure there are parts you left in your soul that will never see the light of day, but the parts you did allow us to see are so marvelous! You are truly a gifted writer. I hope the prying helps you heal, as I feel there is still healing for you that needs to happen. Opening the wound like you have may rip out the scar tissue to let new flesh grow again, and I hope it does. But what do I know?

I hope you’re content with having a new fan, at the least.

Big-Un: thank you, oh thank you. The prying has been really kind of awful, but things like this–your wonderful note here–are exactly what’s helping the healing along.

This whole piece was lovely, brave and real. Thank you for sharing it, and keep writing.

Thank you, Dorli!

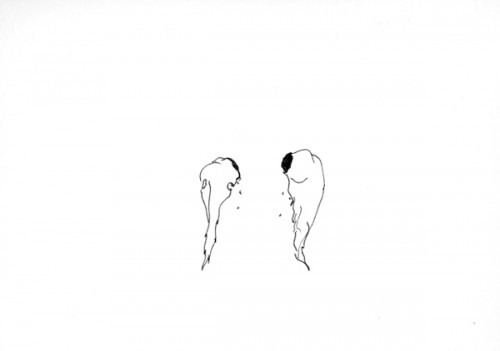

I can’t really add anything that hasn’t been said above, but just to reiterate, you are a fantastic writer. To have rendered so well, so candidly and so movingly these parts of your life is something I find unfathomably, heartbreakingly beautiful. The art by Astrid Cravens throughout is phenomenal too.

It made me want to create again, to drag myself out of the haze in which I’ve found myself for the past two years… thank you.

I’m deeply grateful, Aodh, for your generous words. (And I agree about Astrid’s art!)

I just want to add my voice to the chorus of those praising this fine essay. There’s far too little of this sort of writing out there — incredibly brave, moving, unpredictable — and bleak as hell. Thank you for writing it.

That, and I’m leaving it open for a reread.

Alexander: a sincere thank you for taking the time to write this heartening comment.

Thank you so much for writing this. Reading it has helped me in a number of ways and I really hope that writing it has helped you too.

Sarah, I’m so glad that it’s been a good thing for you–reading this piece–and very grateful for your comment. If writing these chapters didn’t help me (I still can’t be sure), hearing from people absolutely has. Thank you.

I’m enthralled with this piece, I just read it twice in a row. I love the way you told the story, in beats and tangents, like leading us down your train of thought. I can’t stop thinking about it. I feel fuller and so glad to have read it, to discover your work, and to resonate with your voice. Thank you for this. It’s such great work.

Marina, I’m so happy that you connected with Blue Spark–and even more happy that you were moved to write this note. Thank you, thank you for taking the time to do so.

I don’t quite know fully how I got to your article tonight Nelly, but thanks. My whirligig’s been flying off the charts in opposite directions and you’ve stopped it and helped me breathe for a bit, that’s for sure! Mid-read I found myself texting very old friends after this who’ve been my numero uno fanatics for so long, just because they’re nice, and telling a few who’ve been there just how insanely much they mean to me…regardless, the chance to breathe and not succumb to mundanity on the first midnight of the month has settled ideals pretty deep for me. I’d like to have a personal chat some time if possible, let me know. :)

Stephen, thank you for this note. I’m so happy to know you were moved to connect with your old friends–and with me.

There’s a contact box here:

http://nellyreifler.com/cms/contact/

I will write back.

So I am not even a “reader” and was directed to the essay from the wiki site for Elliott, wow! Thank you so much for opening me up to an art form besides music. I feelike I somehow know you and was there , I would beleave that that is what true writing is about. You have a new fan!

Deeply moving.

I was enthralled with the flow of emotional darts blazing past my eyes as I delved further and further into your body of work. I lost track of time and space as I read. I drifted off and zoned out to a new land in my imagination that was colorful, cold, bold, and wet. I could almost taste what I smelled, as the scents were so vividly expressed through your words of reflection and pain. Thin and light, slight and salty. God bless you.

Hi Nelly. Just wanted to tell you how much I enjoyed your writing, and that my wife Ginny enjoyed it, too. Probably, like lots of people, I got to Blue Spark by way of ES. I like that his is just one of many of your reflections, though. I especially like the vulnerable and honest narration. Blue Spark has really sort of captured us and we’ve spent lots of time with it. There’s so many disparate ideas in there and we’ve enjoyed passing them back and forth. Even the sad ones. Maybe all the people who had to leave the world are happy now and waiting for the rest of us. It’s a nice thought anyway. I hope this little message finds you happy. Thanks for reading it. :)

Pingback: What I Have Learned About Elliott’s Girlfriend Over The Years – Justice for Elliott Smith

Pingback: Elliott Smith’s College Classmate Discusses Their Last Meeting And The Circumstances of His Death – Justice for Elliott Smith