“IT’S JUST A PERSONALITY CRISIS – you got it while it was hot.” -New York Dolls

I first encountered the New York Dolls in 1995, when I was twelve. While school-friends with big sisters were being introduced to Oasis, Blur and Pulp, I had been going through boxes of my dad’s cassette tapes, and I had fallen in love with the Sex Pistols. From then on, I’d been making regular trips to local record shops to pick up whatever punk and new wave records I could find. A couple of old punks I knew were happy to encourage my obsession – one was a neighbor who still owned a tartan kilt and a Damned t-shirt that he would squeeze into for reunion gigs, and the other worked at Mike Lloyd’s Music, where I bought most of my albums. Dave, the neighbor, mentioned the Dolls to me at some point that summer, so I ordered in the compilation album Rock & Roll, which had been released the year before. ”You’ll be wearing make- up soon,” my friend said as I handed over my tenner.

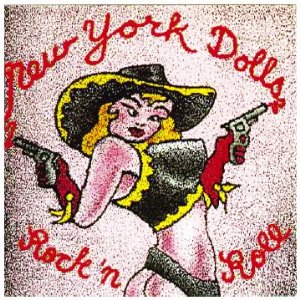

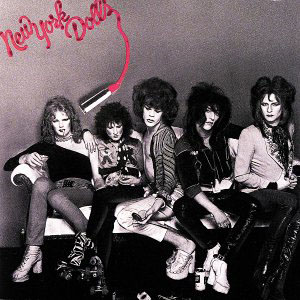

The cover wasn’t anything like the standard image of sullen young men in leather jackets that you found on most punk album covers, and it was a million miles from the Ben Shermans and parkas sported by the Britpop bands in the NME too. The front featured a cartoon pin-up image of a blonde woman in a bikini and Stetson, brandishing two revolvers. The name “New York Dolls” was written in lipstick traces between the barrels of the guns. On the back was a photo of the band. Their black outfits blended into the background, but standing out against the gloom were shocking glimpses of flesh – an exposed midriff, a bared shoulder – a bright yellow silk scarf, and two pairs of gleaming white platform boots. Most impressive, all five band members were staring defiantly from the sleeve, challenging me to hold their gaze. This was going to be something else.

The cover wasn’t anything like the standard image of sullen young men in leather jackets that you found on most punk album covers, and it was a million miles from the Ben Shermans and parkas sported by the Britpop bands in the NME too. The front featured a cartoon pin-up image of a blonde woman in a bikini and Stetson, brandishing two revolvers. The name “New York Dolls” was written in lipstick traces between the barrels of the guns. On the back was a photo of the band. Their black outfits blended into the background, but standing out against the gloom were shocking glimpses of flesh – an exposed midriff, a bared shoulder – a bright yellow silk scarf, and two pairs of gleaming white platform boots. Most impressive, all five band members were staring defiantly from the sleeve, challenging me to hold their gaze. This was going to be something else.

When I got home and put the record on, I was blown away. The mad racket of the Dolls combined the excitement and danger of the English punk bands I loved, but there was something more too. Like many of the early US punk bands, the Dolls had stumbled upon their sound while trying to be something else entirely. In their case, they were aiming for the Shangri-La’s, but their unpolished playing and amphetamine-fueled energy meant that the Dolls were never going to appear on Phil Spector’s Christmas Gift For You. I didn’t know that at the time – but I did know that the hormonal intensity of the music, and David Johansen’s elegantly wasted lyrics (“everyone’s going to your house to shoot up in your room / most of them are beautiful but so obsessed with doom…”), were the perfect fit for a lonely boy on the brink of adolescence in Stoke-on-Trent, a grey Northern industrial town which had seen the industry ripped out in the Eighties, and a gaping hole left in its place.

Was my friend right about the make-up? My other big discovery of 1995 was the Manic Street Preachers, who were on hiatus following the disappearance of lyricist, figurehead and sometime guitarist Richey Edwards. Like the Dolls, the Manics looked like they’d just drunkenly raided your aunt’s wardrobe, and they combined a penchant for big girls’ blouses with a defiant aesthetic summed up by spray-painted slogans like “Iconoclastic Glitter” and “Generation Terrorists.” The escapism of the Dolls and the cultural politics of the Manics were inexorably linked with the way they looked, and I wanted to signal my allegiance through the medium of Boots 17 eyeliner and sparkly nail varnish borrowed from a girl in class.

Was my friend right about the make-up? My other big discovery of 1995 was the Manic Street Preachers, who were on hiatus following the disappearance of lyricist, figurehead and sometime guitarist Richey Edwards. Like the Dolls, the Manics looked like they’d just drunkenly raided your aunt’s wardrobe, and they combined a penchant for big girls’ blouses with a defiant aesthetic summed up by spray-painted slogans like “Iconoclastic Glitter” and “Generation Terrorists.” The escapism of the Dolls and the cultural politics of the Manics were inexorably linked with the way they looked, and I wanted to signal my allegiance through the medium of Boots 17 eyeliner and sparkly nail varnish borrowed from a girl in class.

This wasn’t an easy decision in Stoke. Even today, after the mainstreaming of emo, there are still areas where to put on make-up as a boy is a provocative gesture, an invitation to comment, abuse and violence. Back in 1995, away from the big cities, it was like drawing a target on your forehead. Fortunately, teenagers being the resilient creatures they are, black eyes and broken noses seemed like badges of honor; getting chased down the road by mods for wearing a feather boa might be frightening, but at least it confirmed my sense that I belonged elsewhere. It was the simplest, most direct way of saying that I wasn’t accepting the bleakness of life in Stoke, and was looking for something more exciting. I already felt out of place here; my appearance made it obvious. Quentin Crisp, another icon, said in his memoir The Naked Civil Servant, “We should be existential – that is to say, swim with the tide but faster.” The Dolls were my vehicle for doing this; taking a natural inclination and wearing it as a beacon of intent.

After the shock of hearing “Personality Crisis,” “Looking For a Kiss” and those other incendiary songs for the first time, I had to find out more about the Dolls. If the Clash, the Pistols and so on were a reaction to prog rock and industrial turmoil, as the books suggested, what sort of weird goings on had given rise to this band of misfits?

At school I learned about the American Dream, the great myth of the modern age which, I was told, involved the acquisition of land and family, but we also read Capote’s Breakfast At Tiffany’s and later The Great Gatsby, opening our eyes to flamboyant hustlers trying to make their way in the big city while flouting social conventions and the law. What did these characters tell us, as teenagers? That maybe if you didn’t naturally fit with the values of polite society, well, if you show enough chutzpah then polite society might come banging on your door.

Following the successes of the Civil Rights movement in advancing the cause of blacks and women in the Sixties, other minority groups were beginning to use this sense of style and outrageousness to secure their own space within the acceptable boundaries of society. The middle classes had moved out of the inner cities, allowing gay, lesbian and student communities to find safe spaces within the concrete jungle. In New York, there was Warhol’s Factory, with its kitsch, trashy appropriation of mass culture. In 1969, New York’s gay subculture was forced into the public eye by Stonewall, where a raid on a bar left gays and drag queens literally fighting in the street against straight society, represented by the police. The violence of the confrontation forced the press and public to pay attention, with the New York Daily Times covering the events on its front page. In the aftermath of the protests, Greenwich Village residents formed activist groups to fight for the right to express their sexuality without fear of arrest.

Following the successes of the Civil Rights movement in advancing the cause of blacks and women in the Sixties, other minority groups were beginning to use this sense of style and outrageousness to secure their own space within the acceptable boundaries of society. The middle classes had moved out of the inner cities, allowing gay, lesbian and student communities to find safe spaces within the concrete jungle. In New York, there was Warhol’s Factory, with its kitsch, trashy appropriation of mass culture. In 1969, New York’s gay subculture was forced into the public eye by Stonewall, where a raid on a bar left gays and drag queens literally fighting in the street against straight society, represented by the police. The violence of the confrontation forced the press and public to pay attention, with the New York Daily Times covering the events on its front page. In the aftermath of the protests, Greenwich Village residents formed activist groups to fight for the right to express their sexuality without fear of arrest.

This is the melting pot from which the Dolls emerged. A loose gang of streetwise teens from the suburbs, who had congregated around Queens, the New York Dolls were David Johansen (vocals), Johnny Thunders (guitar), Sylvain Sylvain (guitar), Arthur ‘Killer’ Kane (bass) and Billy Murcia (drums – replaced by Jerry Nolan after his death in 1972). They weren’t the first American band to listen to David Bowie and put some make up on, but whereas Alice Cooper and Kiss asserted their masculinity with borderline misogynist lyrics and violent onstage posturing, the Dolls took everything to a more unsettling place, quickly becoming known for what Morrissey biographer Mark Simpson called their “crazily cranked up” glam sound and a look that moved beyond kitsch: it was “precariously close to out and out drag.”

One thing we learned in lit class was that there was rarely a happy ending for those who tried to make a name through unconventional means: Golightly and Gatsby could shine briefly, but they never got to claim the status they desired. Likewise, there was something inherently doomed about the Dolls. There are American icons who’ve made a virtue out of looking outrageous, being sexually adventurous, getting high or making political protests, but it’s rare to see anyone combine all four. The Dolls’ utter determination to stand alone was to prove unsustainable, even in a relatively liberal era.

The Dolls’ appearance was the first barrier between themselves and the moral majority. Drag is associated in common thinking with the desire to become female, or transgender: it is perceived as a rejection of masculinity. When a man dons women’s clothes, and adopts an effeminate air, he lessens himself in the world’s eyes – he abandons the protective cloak of masculinity and is seen as weak, open to ridicule. This was not the Dolls’ attitude though. As Simpson noted, “They were androgynous, but they weren’t eunuchs.” They appropriated female attire, but they wore it as men, creating what Simpson called “a fuck-you gender fuck.” Their decision to “mix cowboy stuff with glamorous 40s girl’s stuff” was an arch attempt to subvert concepts of masculinity.

Then the Dolls opened their mouths. Greil Marcus observed in Mystery Train that American music is closely linked to the Dream, “taking its energy from the pursuit of happiness… the idea that you can always get what you want.” Johansen and Thunders, on the other hand, reveled in the seedy underbelly of urban life. While Sinatra sang about working hard to make it in the city that never sleeps, the Dolls recast New York as a modern day Babylon, with “two girls for every boy.” Glen Campbell’s “Wichita Lineman” Is as much a hymn to blue collar work and the railways which carried pioneers West, as it is a love song, but there is no such ambiguity in the Dolls’ “Subway Train.” Johansen portrays himself as a Flying Dutchman figure, “Cursed, poisoned and condemned,” haunting the underground system “dressed in rags,” on an endless search for debauchery.

Then the Dolls opened their mouths. Greil Marcus observed in Mystery Train that American music is closely linked to the Dream, “taking its energy from the pursuit of happiness… the idea that you can always get what you want.” Johansen and Thunders, on the other hand, reveled in the seedy underbelly of urban life. While Sinatra sang about working hard to make it in the city that never sleeps, the Dolls recast New York as a modern day Babylon, with “two girls for every boy.” Glen Campbell’s “Wichita Lineman” Is as much a hymn to blue collar work and the railways which carried pioneers West, as it is a love song, but there is no such ambiguity in the Dolls’ “Subway Train.” Johansen portrays himself as a Flying Dutchman figure, “Cursed, poisoned and condemned,” haunting the underground system “dressed in rags,” on an endless search for debauchery.

Possibly the most important Dolls song is “Human Being,” from the aptly titled second album Too Much Too Soon. “Human Being” begins with a traditional 12-bar blues riff, the most American of musical forms, but this is swiftly drowned out by wild guitar flourishes from Thunders and jazzy trombones (both in their way representing subversive musical genres), as Johansen declares “If you don’t like it, go ahead and find yourself a saint.” Throughout the song’s five minutes, the androgynous, drug-fuelled low-life New Yorkers assert themselves ahead of the “plastic dolls” of the daylight world. The verses are made up of a series of challenges to an unnamed member of straight society, while in the chorus, the singer proclaims his right to “act like a king,” “start to dream” and “get a bit obscene,” setting up an opposition between the human beings who “walk around with their heads hung down” and the “riff-raff” like him who “hold their heads so high.”

Johansen’s sense of otherness is encapsulated in the final verse with the term “Hollywood refugees.” Flamboyant theatricality is central to the Dolls’ subversive thrill. In the final voice, he surveys the straight world, where dehumanized figures “bounce around from machine to machine,” declaring it “too appalling for me” – with a cinematic flourish, he “colors up history” and makes it “just what I want it to be.” He makes up the face of straight America, applies lipstick to the Statue of Liberty and creates a daring new identity for his fans to embrace.

Unfortunately for the Dolls, every action after this point served to undermine their attempts to keep ahead of the tide. In the latter stages of their short career the Dolls found their musical output overshadowed by drug use and the controversy generated by their adoption of sexualized communist chic on the Red Patent Leather tour (1975). It is hard to imagine two activities more diametrically opposed to traditional American values than injecting heroin and parading in PVC Red Guard outfits. Drug addiction sublimates the identity, and the pursuit of happiness in supplanted by the pursuit of more heroin. Just as importantly, while freedom is central to (post-emancipation) American identity, the addict is never his own man. Inverting the idea that “the customer is always right,” the junkie is at the bottom of the drugs pyramid, as Lou Reed understood: “He’s never early, he’s always late / First thing you learn is you always got to wait.” The defiant protagonist of “Human Being” is reduced to waiting on street corners for his man to show. A bit like the date who never calls back.

The Red Patent Leather tour was an even worse mistake. The brainchild of new manager and arch-provocateur Malcolm McLaren, the tour was an attempt to reposition the Dolls in an increasingly aggressive alternative music scene, characterized by groups like Television and The Ramones. During the Vietnam War, touring the South and performing in front of a giant Soviet flag while dressed like “the rent-boy regiment of the Red Guard” can only be seen as a deliberate provocation. The hammer and sickle backdrop was a rejection of the Stars and Stripes and the capitalist system on which the American Dream of property-ownership depends. This attitude requires total commitment, but the Dolls were drifting, allowing someone else to control their image for the first time, either too depressed or strung-out to notice. They’d been caught up in someone else’s tide, and now there was nowhere else for the band to go: they split midway through the tour.

Judged on their three-year existence, the Dolls appear to have little impact on popular culture – two poorly received albums and a footnote in the history books as a cautionary tale for young bands hooked on the myth of the rock and roll lifestyle. However, they played a part in a wider cultural battle, and their iconoclastic attitude towards image and music was to become relevant once more.

Judged on their three-year existence, the Dolls appear to have little impact on popular culture – two poorly received albums and a footnote in the history books as a cautionary tale for young bands hooked on the myth of the rock and roll lifestyle. However, they played a part in a wider cultural battle, and their iconoclastic attitude towards image and music was to become relevant once more.

~

After 9/11, the feminist critic Susan Faludi noticed a shift in public attitudes, specifically the American view of masculinity. Since the Seventies, she argued, the traditional industries and roles which defined male identity had been in decline, prompting her to write about “the betrayal of modern men” in Stiffed. This economic change was matched by a social one. The cultural battles in which the Dolls had played their part, including the movements for women’s and gay rights, may not have been entirely won, but at least the boundaries of acceptability had shifted. Following the attacks on the World Trade Center, however, attitudes had been abruptly retrenched and suddenly the media was filled with images of fire fighters and other blue-collar heroes. Faludi noted that, “Within days of the attack, a number of media venues sounded the death knell of feminism” and the end for the “shaved-and-waxed male bimbos.” Once again, the world needed the Dolls, as a voice for individuals who rejected the roles society ascribed to them, and it was a fey, bookish man from the North West of England who would bring them back – Morrissey. The former Smiths singer had written a Dolls fanzine when he was a teenager, and was now able to acknowledge their influence on him by offering them a slot at the Meltdown festival in London.

After the split, the Dolls had pursued divergent paths. Thunders enjoyed the most success with his band The Heartbreakers, who took the Dolls sound but adopted a resolutely hetero vibe, all leather jackets and gangland imagery, their artwork bearing tags like “DTK – Down To Kill” and “LAMF – Like a Mother-Fucker.” He was joined in this venture by Nolan, and both were to die within months of each other in the early Nineties. Killer Kane drifted, suffered from depression and alcoholism, and became a Mormon. Sylvain drove taxi cabs for a while. Most interestingly, Johansen adopted a traditional American idiom, growing his facial hair long and performing rootsy folk music with his band The Harry Smiths.

Reuniting bought the band to their biggest audiences, starting at the Royal Festival Hall on London’s South Bank. I didn’t see them that night but was there when they played at Move festival in Manchester a couple of weeks later, reveling in the incongruous site of the aging Dolls blasting out their ragged anthems in daylight at a sports arena. With typical Dolls luck, Kane died shortly after the first reunion concert, but a loose collection of musicians played under the Dolls moniker, led by Johansen and Sylvain, touring the US before heading to the studio to record their first album in 32 years.

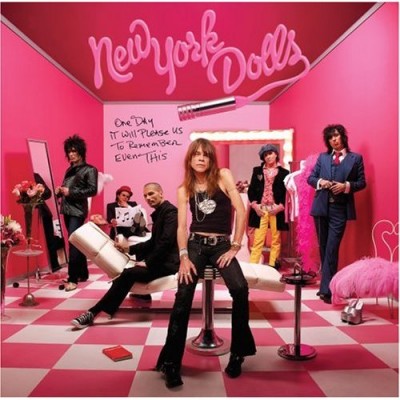

I remember when One Day It Will Please Us To Remember Even This was released, a sunny day in 2006. By this point, I’d escaped Stoke and was living in central Manchester, playing guitar in the band Billy Ruffian. The music scene in the North then was deeply suspicious of anything which smacked of pretence, with a focus on “proper music” – a timeline stretching from The Beatles, The Who and The Jam, skipping past most of the Factory scene, through to Madchester and Oasis. The likes of New Order and the Stone Roses had all the color sucked out of them in this version of musical history. Any ambiguities in their music were buried under the noise of beery lads chanting along. The city center bars which played their music were aggressive places where you could get bottled for scuffing someone’s trainers. The more flamboyant musical types fled to seedy bars on the edge of town, where we danced to The Velvet Underground and swapped clothes into the early hours.

The bands doing the rounds on the local gig circuit were unimaginative pastiches of what had gone before. One particularly awful example was the much-hyped Young Offenders’ Institute, a Happy Mondays rip-off with lyrics full of drug and dole clichés, who had been taken under the wing of ex-Factory Records boss Tony Wilson. Otherwise it was a parade of dull thirty-somethings with ironed t-shirts and pristine Fender Stratocasters, or earnest acoustic troubadours. By contrast, Billy Ruffian adopted a strict ‘no beards or trainers’ policy, wore suits at all times, and sang songs about being possessed by the ghosts of dead ancestors. We were seen as outsiders, and responded by declaring a fatwa on the Arctic Monkeys after their drummer wore tracksuit trousers onstage at Glastonbury. I was looking for something to inspire me in the midst of all this drudgery, convince me that going alone was the right option – and here were the Dolls again.

It was the only time I’d felt nervous putting a record on. I’d been to the Sex Pistols reunion gigs, but there was never going to be new material from them. With Joe Strummer dead, a Clash comeback was impossible too. Of the three legendary groups I’d grown up listening to, this was the one time I would be able to be there to hear new recordings. Fortunately, I wasn’t let down. Musically, the album was strong, combining Sylvain’s girl group influences with a beefed-up modern production, guest spots from counter-culture icons like Michael Stipe and Iggy Pop, and some excellent guitar-playing from Thunders replacement Steve Conte, but it was Johansen who really shone. Older and wiser, he simultaneously embraced the Dolls’ shot at redemption, and realised the absurdity of the situation. On the live recording of their Festival Hall, he tells the crowd, “Two weeks ago, I was this bearded folk singer – kinda like John Martyn – and now I’m like one of the Scissor Sisters.” The album was dedicated to the deceased Dolls, and also to “the joyful participants of the Kali Yuga.” According to Vedic teachings, the Kali Yuga is a stage of the world’s development marked by discord, strife and spiritual darkness. This sense of conflict is evident as Johansen attempts to create a joyous sound to pay tribute to his fallen comrades while constantly fighting against his own emotional turmoil.

At times, he displays an almost childish enthusiasm, in the opening track’s celebration of “running round the stage dressed like teenage girls,” or in “Dance Like A Monkey’s” playful baiting of the religious right (“c’mon shake your monkey hips, my pretty little creationist”). Elsewhere there is a profound melancholia absent from the classic lineup’s work. “Plenty of Music” curses the “superfluous beauty” of the Dolls in their heyday, which wasn’t enough to save them from disaster, while even on the upbeat “Rainbow Store” Johansen declares, “My emotional landscape was strip-mined.”

Maybe the perfect mix of these traits was final track “Take a Good Look at my Good Looks,” a Spectorish ballad of arrogance and resignation: “Take a good look at my good looks, and close your eyes – take a picture in your mind, ‘cos I’ll be gone.” I listened to the album on repeat with my girlfriend and our housemate as we drank vodka into the early hours. To this day, no other album makes me feel so alive. Billy Ruffian split up a couple of years ago, citing “incompatible sexual differences.” There’s talk of a reunion gig soon.

~

Nowadays, I don’t wear so much make-up – a nice blue eye shadow on special occasions – but I do still seem to attract attention from Shouting Men in the street, whether I’m on my way home from work or talking my daughter for a walk. The worst thing that happened to me was being beaten up outside a club in Manchester’s gay village. I ended up in hospital, and went deaf for a week because of a blood clot round my eardrum. I don’t feel in danger any more though. The comments range from the amusing – “Fucking hell, it’s Alan Cumming” from a football fan at Wembley, a comment which reflects well on both shouter and shoutee – to the bemusing (“oi, Mark Knopfler!”), but are rarely hurtful. I see that sort of attention as one of the occupational hazards of looking the way I do – I’m in the crosshairs, because my hair makes people cross.

I still listen to the Dolls just as much though, mainly the more recent albums, and I’ve been to see them in concert a few more times too. When they played in Liverpool in 2006, their first proper UK tour in 32 years, I found myself standing next to three boys, the oldest of whom must have been 11. They’d been to see former Sex Pistol Glen Matlock perform in London the week before, and couldn’t believe they were about to watch Johansen and co in real life. It was a heartening moment, a ceremonial torch-passing. And when I die, I want the Dolls played at my funeral. After Wreckless Eric’s new wave tear-jerker “The Final Taxi,” my body will be blasted into space/consigned to the flames/thrown overboard while the crowd listens to “Take A Good Look At My Good Looks” – the sound of the band which inspired me to take my own stand against boredom and despair, to think about who I was, embrace it, and then try to swim with the tide, but faster.

http://open.spotify.com/user/joed_sandiego/playlist/3zB14Y0qUGBlZiinFaenBh

Beautiful.

Wow! After all I got a weblog from where I can genuinely get valuable data concerning my study and knowledge.

A motivating discussion is definitely worth comment. I do think

that you should write more about this topic, it might

not be a taboo matter but typically people do not discuss these subjects.

To the next! Kind regards!!

Hello, every time i used to check web site posts here in the

early hours in the daylight, since i like to find out more and more.

Heya i am for the primary time here. I found this board and I in finding It really helpful & it helped

me out much. I am hoping to give something back and aid others such as you

helped me.

Admiring the time and energy you put into your blog and in depth information you offer.

It’s good to come across a blog every once in a while that isn’t the same old rehashed information. Excellent read!

I’ve saved your site and I’m including your RSS feeds

to my Google account.

It’s going to be end of mine day, but before ending

I am reading this great piece of writing to increase my

know-how.

Good day! Do you use Twitter? I’d like to follow you

if that would be okay. I’m undoubtedly enjoying your blog and look forward to new

updates.

I’m extremely inspired along with your writing abilities

and also with the format for your blog. Is that this a paid topic or did you modify it yourself?

Either way keep up the excellent quality writing, it is rare to see a great weblog like

this one these days..

I was able to find good information from your blog articles.

I simply could not depart your web site prior to suggesting that I really enjoyed the standard info a person supply on your guests?

Is going to be back continuously in order to check out new posts