IN NEW YORK this spring is an art biathlon with a Bi- and Triennial promising a definitive take on art today. Seeing the Ennials in one day is an Olympic event: two museums on opposite sides of town, one up, the other down. Between them are ten stories of art and 101 artists: 50 at the Whitney and 51 at the New Museum. Luckily this brand of athletic endurance art-seeing can happen only once every six years; that’s when the exhibits coincide.

There, though, the coincidences end. There’s only one crossover artist. One show has many artists often exhibited in New York; the other has names rarely, if ever, seen in the U.S. If the two Ennials would, could, yield consensus, it would be remarkable. It’s even trickier given one has only four U.S. artists (though many Americans from Mexico, Colombia, Brazil, Argentina and Peru). The other could be called the Brooklynnial. Like the borough, it’s full of crafty, homemade work.

This year’s Biennial has been praised lavishly, this in a town where dissing it is blood sport. I started out willing myself to love pieces I didn’t like, even by artists I did. Maybe the reviews got my hopes up too high, or maybe the blame should fall on the roped line outside making it feel like a nightclub, even at 10:45 AM before the museum had opened. Then there was the guy in the ill-fitting suit with the heft and voice of Tony Soprano barking into a cellphone, “I’m at the fucking Whitney. Where are yous?”

Inside, two different artists had recreated their studios. One, Dawn Kasper, is virtually living and working in the Whitney for the duration. When I was there, she played the B-52s on a turntable, and in his review Peter Schjeldahl insisted we talk to her, that she was friendly. I didn’t. I still have that hands-clasped-behind-my-back-don’t-touch-the-art ethos. Instead, “Rock Lobster” just wormed its way into my head, and she hugged an old friend. More than that, I was sad that the Whitney didn’t give her a space with windows given that she’s showing up five days and more than 40 hours a week.

Performing (as opposed to performance) art had a prominent place in the show. The impermanence and evanescence was thrilling, at least as an idea. Giving over to a live moment that can’t be bought or sold is like giving the finger to the art market. While every other creative economy is imploding in the digital age, the capital-A art of the art world is doing great because it can’t be replaced digitally. It’s about the object and aura and some personal relationship with it. It also doesn’t hurt that the 1% is doing just fine and enjoys jetting around the world according to the burgeoning calendar of art fairs. As if an answer to the expectations of art now, the rest of the work also has a humble quality.

Downtown, the Triennial is called “The Ungovernables,” an overlabored title if ever there was one. (Well done, Whitney for sticking to “Biennial 2012.” On occasion they’ve been known to name the shows like “Day For Night” in 2006, not to mention the names – often bad – others give the surveys.) Down on the Bowery, the museum sported heavy-handed text about colonialism and natives and offered a view on art about as different from the Biennial as you can get. Yes, there was some handmade work, rough around the edges. Someone wrapped a basketball in a crown of thorns and arrayed other twigs in vases, the slightest work in the show. Uptown the Biennial felt a bit self-absorbed, about me and I, and the other, the Tri, more about us and they, asking bigger, more urgent questions and using the art to engage.

Pratchaya Phinthong's ever-increasing pile of Zimbabwean money grows with ever-increasing Zimbabwean inflation.

The Triennial looked at our involvement with each other and the world. Pratchaya Phinthong’s stack of Zimbabwean dollars on the floor is a subtle comment on art, inflation and dictatorships as well as value in the art world. He took an investment of 5000 Euros and traded the money with average people he met online, building community and circumventing currency traders. The piece also has a beautiful near-minimalism there on the floor. Catty-corner from it is Amalia Pica’s Venn diagram, with its Dan Flavin colors. At first it appears as a pink circle projected on the wall, then as you get close, right behind the projector, a pale blue circle is overlaid. Venn diagrams are hip these days in graphic design and info-graphics for their ability to summarize quickly with little need for text, but they were once illegal. Yes, in Argentina during the military junta, officials feared they’d encourage collectivism, and here the diagram only appears when someone triggers the motion sensor. It takes people to make it.

Danh Vo’s lyric sculpture “We The People” looks a like a low-rent Serra. Made of copper not steel, it’s not heavy enough to kill. The waving panels aren’t abstract but pieces of the Statue of Liberty. Vo, a Vietnamese artist living in Berlin, remade Lady Liberty, getting her fabricated in China. She’s made with the same technique used on the original, pounding out the copper like beating a car panel. Here, like the original, Liberty is no thicker than two pennies, which seems a lovely take on impermanence and value if ever there was one. With subtle comments on politics, globalism, manufacture and art itself, I wouldn’t call any of these artists “Ungovernable,” maybe “questioning.”

The Statue of Liberty was remade in China; the panels are never assembled, never complete in a state of permanent diaspora.

Now, liking so many artists in a survey like this is rare. Back in the ‘06 Biennial I remember only one, a video by Diana Thater, but here I could go on and name more than a dozen, like Rayyane Tabet’s ghostly sculpture of his room in Lebanon remade in sagging canvas; or Hassan Khan’s video of two dancers, one white the other Arab, almost fighting to a pounding Shaabi beat (Egyptian dance music heavy on the bass, mixing tradition and techno). It’s rave as rage. Meanwhile Pilvi Takala occupies Deloitte & Touche for a month with a job in the marketing department but does no work. The videos of her and her colleagues’ confusion are unsettling as if belying the lie behind work and offices.

Most eloquent of all Jose Antonio Vega-Macotella trades time in an equal exchange for labor with prisoners in Mexico City. He does errands for them on the outside, lobbying for one’s release, meeting another’s ex-girlfriend, seeing one’s son take his first steps, smuggling in contraband. In exchange the prisoners make art. One tracks 10,000 pesos through the jail in a grid of fingernails, another catalogues the cigarette butts in his cell. Still another, the one Macotella lobbies for, charts his footprints through the prison. The objects of exchange are poignant and frail. The piece is about time and money, about doing time, about what time is worth.

He wrote in Vice Magazine: “Time has been appropriated by institutions. They’ve taken it away from us. In this somewhat Marxist mind-frame, I clearly saw that time has been transformed into production and then production into distribution. Our work time is converted into salary, and our leisure time into consumption.” The explanation helps, but there’s something more moving and beautiful in the work like one of the prisoners recreating a Veronese with other prisoners’ tattoos.

While Vega-Macotela watched Superaton's son take his first step, the prisoner catalogued all the cigarette butts in his cell.

~

I have no idea how to evaluate art, not really. I’ve struggled with this since going to grad school for a PhD in art history in contemporary art and theory (I dropped out); then at the Whitney Program, kind of like a finishing school for the art world that the museum runs for young artists and curators; and here, writing about art now. For me there’s some formal quality involved. Yes, does it look good? But, I’m also fine with reading the wall text first and then looking at a piece. A friend, a painter, has said if you need to read the press release to get a work of art (generally the case for conceptual work), if it requires language to understand, then the piece should just be language, text. I disagree. Obviously.

One of my favorite pieces of art over the last decade was by someone whose name I don’t even know. The piece was in a group show I hadn’t intended seeing in an over-lit corridor at the back of an arts complex in London. The artist stuck a bunch of dead insects to paper. They all had names and personalities. The flies and roaches had died natural deaths. There were no splats of fly guts and no animosity at the bugs’ intrusion, only love. He wrote about each one. Each had a distinct personality. He’d given them names. They’d been his friends. He was in jail, and the piece gave truth to his aching loneliness. With his insects, his pets as it were, he found love, warmth, something that would conquer all. It had the same quality of Macotella’s piece, creating a larger truth, and also of the best work in the Biennial.

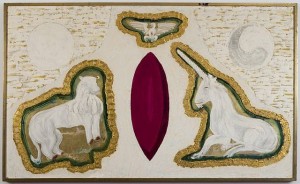

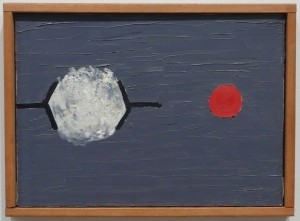

That sense of loneliness and longing suffused Forrest Bess’s art. While the Biennial promises to talk about where art is now, featuring work made over the past couple years, his wasn’t made recently, not even in this decade. He died in 1977 in relative obscurity. He made luminous, intimate paintings of his visions. The pieces are somewhere between William Blake and Vincent Van Gogh, with a dash of Rouault. A room of the museum is given over not just to his paintings but his experiments on himself. He performed self-surgery to turn himself into a hermaphrodite. He wanted to transcend masculinity and femininity. He felt then he’d truly understand, truly be alive and find immortality. The photos and descriptions are horrible to see, but they were part and parcel of his artwork. He wanted them all exhibited together, something his dealer (Betty Parsons, who also showed Rothko and Pollack) refused.

Seeing his life’s goal achieved and his paintings and correspondence (often pleas for understanding) shown together is moving – both that he got his wish but also to witness the depth of his longing. This was more than a full decade before performance art moved to the body with feats of endurance that led artists to live in a gallery with a coyote or shoot themselves, and masturbate under the floor of a gallery or even carve makeup in their faces. None were as radical in trying to defy the reality of the world or reach beyond the self. Nor were they as tragic. Bess died penniless, largely alone back in his hometown, in small-town Texas, where neighbors helped him get by.

One of Bess's small paintings of his visions, visions that saw himself try to turn into a hermaphrodite.

Now he shines over the Biennial like a guiding spirit, and the other work, which is often personal and private, seems stronger in his light. From him, they gain meaning, struggle, longing. With this Biennial, though, he’s being subsumed in the art world. This month Christie’s is having a large exhibit of his work and a private sale. What’s radical gets quickly absorbed and taken out of context. His pictures are pretty. They are objects. They will look nice on rich people’s walls. I wonder what Bess would say about that and the work in both Ennials, that fight between self and the other, us versus them and looking for a place in the world.