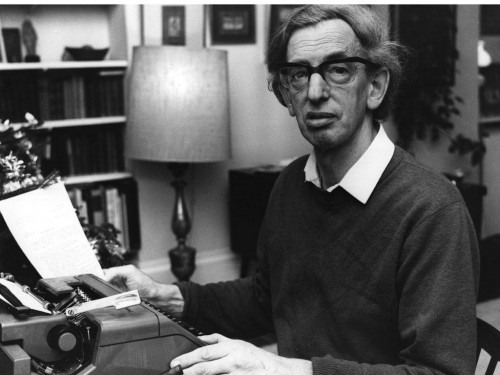

LAST WEEK, the eminent British historian Eric Hobsbawm died, at the age of 95. As it happens, I’ve been working my way through his masterful four-volume series this year—I finished The Age of Revolution and The Age of Capital and am halfway through The Age of Empire—so I am keenly aware of the magnitude of his loss. The collective brainpower of the world is a bit dimmer now.

Hobsbawm was a freak of nature. He was to historians what Usain Bolt is to sprinters. His vast intellect, dizzyingly deep and broad knowledge base, uncanny ability to make sense of events that are as complex as they come, and Booker Prize-worthy prose style are unsurpassed in the field. If an analog can be found, one might make a case for Robert A. Caro. But while Caro concentrates his phenomenal attention upon a narrow slice of the past—Robert Moses, LBJ—Hobsbawn displayed a similarly intense understanding of all of world history, from 1789 to the present. In a discipline in which one tends to specialize, his historical series was, and is, an astounding feat.

Although Hobsbawm was an outspoken and unrepentant Marxist—his political support for the post-WW II Soviet Union drew much criticism, although he was hardly the only intellectual fooled by Stalin—his history is not a treatise in Why Marx Was Right. If I take anything from Hobsbawm, it’s that the past is incredibly complicated, and resists all attempts at broad generalization.

Here are six things I’ve learned (so far) from his books:

1. Economic systems, like political systems, are constantly in flux.

In the lofty perch of 21st-century America, even in its current precarious financial state, we tend to regard our economic system as a given, as inherent to our existence as water or air or bad TV. But capitalism, in its current form, is a relatively new innovation that really didn’t get going in full until the middle of the 19th century. The idea that it will forever endure—like the idea that the hegemony of the United States will—is at best magical thinking.

Hobsbawm felt, as did Marx, that capitalism would one day eat itself, that it could not sustain, that a society based more upon sharing and community-oriented living—what was once meant by the word communism—would prevail. Indeed, capitalism is based upon two things: expansion and exploitation. Thus, it requires new markets and cheap labor. But there are no new markets, and we’re running out of workers to exploit. What then? Perhaps growth for the sake of growth is less vital to the future of our species than protecting and developing the abundance what we already have.

2. The poorer and more backwards the people, the more conservative and resistant to change.

When revolution spread across Europe in 1848 like some antibiotic-resistant virus, the Old Guard was able to stamp it out largely by turning to the peasantry for help. Although poor peasants in most cases stood to gain the most from a new world order, they fought these changes tooth and nail.

For monarchies and aristocracies, and indeed for all who rested on top of the social period, [religion] provided social stability. They had learned from the French Revolution that the Church was the strongest prop of the throne. Pious and illiterate peoples like the South Italians, the Spaniards, the Tyrolese and the Russians had leaped to arms to defend their church and ruler against foreigners, infidels, and revolutionaries, blessed and in some cases led by their priests. Pious and illiterate peoples would live content in the poverty to which God had called them under the rulers which Providence had given them, simple, moral, orderly and immune from the subversive effects of reason. (Age of Revolution, 1789-1848, p. 280)

In this sense, nothing has changed. “Gay marriage is an abomination” and “Obama is a Muslim” and “These damned Mexicans are stealing our jobs” are nothing more than modern-day appeals by the moneyed class to defend Church and State from foreigners, infidels, and revolutionaries.

3. Revolutions are started by the educated middle class—that is, the bourgeois—and then co-opted by more radical elements; once this happens, the initial revolutionaries change sides.

The wave of revolution in 1789-1848 began with an appeal to liberty, fraternity, and equally, and ended with blood on the street. The ones who made the appeal were, in most cases, not the same people working the guillotine. Bear this in mind when watching events unfold in the Middle East, in the aftermath of the Arab Spring.

4. The Reign of Terror, while terrible, was probably necessary. Its well-documented bloodshed pales in comparison to what we’ve witnessed in the 20th century.

The French Revolution, to me, is difficult to understand. Unlike the American version, in which the patriots removed the British, established their own government, and called it a day, the struggle in France took place over decades, and in many incarnations. What people tend to remember is Robespierre and the Reign of Terror—what is generally regarded as a nascent Fascist dictatorship imposed on a nascent republic. That’s oversimplifying things.

The Terror [was] first and foremost the only effective method of preserving their country. This the Jacobin Republic did, and its achievement was superhuman. In June 1793 sixty out of the eighty departments of France were in revolt against Paris; the armies of the German princes were invading France from the north and east; the British attacked from the south and west : the country was helpless and bankrupt. Fourteen months later all France was under firm control, the invaders had been expelled, the French armies in turn occupied Belgium and were about to enter on twenty years of almost unbroken and effortless military triumph….the choice was simple : either The Terror with all its defects…or the destruction of the Revolution, the disintegration of the national state, and probably—was there not the example of Poland?—the disappearance of the country….could the Revolution which had virtually created the terms ‘nation’ and ‘patriotism’ in their modern senses, abandon the ‘grande nation’? (ibid, p. 90-91)

5. Names change; the people we now call conservatives used to be called liberals.

It’s true. Back in, say, 1848, the conservatives wanted a return to the monarchy. Liberals were those who favored liberalizing a state’s economic policies to favor business—basically, well-heeled members of the emerging bourgeois class. Avant garde thinkers like Marx or Blanqui were considered radicals.

So, yes, Mitt Romney is a liberal. But if he and his GOP cohorts were familiar with 19th century history, they would, one hopes, be more strongly in favor of regulation. In the second half of the 19th century, the United States was marked by

the total absence of any kind of control over business dealings, however ruthless and crooked, and the really spectacular possibilities of corruption both national and local—especially in the post-Civil War years. There was indeed little that could be called government by European standards in the United States, and the scope for the powerful and unscrupulous rich was virtually unlimited. In fact, the phrase ‘robber baron’ should carry its accent on the second rather than the first word, for, as in a weak medieval kingdom, men could not look to the law but only to their own strength—and who were stronger in a capitalist society than the rich? The United States, alone among the bourgeois world, was a country of private justice and armed forces….it was during our period that the most notorious of the private forces of detectives and gunmen, ‘the Pinkertons,’ gained their shady reputation, first in the fight against criminals but increasingly against labor. (Age of Capital, p.144)

These are the heady days of deregulation Romney and his laissez-faire ilk want us to return to.

6. The American Civil War was primarily about economic independence from Great Britain.

Slavery was part of the issue, of course. But, as Hobsbawm pointed out, it’s difficult to imagine that retrograde and odious institution lasting much longer than it did. No, the real and less glamorous difference between North and South lay in their respective and opposing positions on tariffs:

The South, a virtual semi-colony of the British to whom it supplied the bulk of their raw cotton, found free trade advantageous, whereas the Northern industry had long been firmly and militantly committed to protective tariffs, which it was unable to impose sufficiently because of the political leverage of the Southern states (who represented, it must be recalled, almost half the total number of states by 1850). Northern industry was certainly more worried about a nation half-free trading and half-protectionist than about one half-slave and half-free. (Age of Capital, 1848-1875, p 142).

When the North prevailed, Hobsbawm argued, the victory liberated America from Great Britain once and for all, and set up the United States as the next great economic superpower. If the South were to be “taken back,” it would be as a rich colony of an opulent faraway motherland.

~

I can’t recommend Hobsbawm’s books strongly enough, especially in light of the changes in the U.S. right now. As Niall Ferguson, a fine historian in his own right and not one ever suspected of Marxist leanings, put it, “That Hobsbawm is one of the great historians of his generation is undeniable. . . . His quartet of books beginning with The Age of Revolution and ending with The Age of Extremes constitute the best starting point I know for anyone who wishes to begin studying modern history.”

RIP, Mr. Hobsbawm.