Kanye West doesn’t care about black people. That is, at least, the message he’s sending with his latest provocation—the co-optation of the Confederate flag. Kanye encourages controversy; he’s become equally renowned for his brash critical outbursts as he has for his musical talents—both of which are in abundance. West has won twenty-one Grammy awards and left an indelible impression on hip-hop production and execution—his introductory album The College Dropout (2004) popularized the use of sped-up soul samples in its beats, channeling chipmunk versions of Marvin Gaye in “Spaceship,” and Luther Vandross in “Slow Jamz.” His 2009 release 808s and Heartbreaks opened the generally aggressive genre to lyrics of sensitive introspection sung through the warble of auto-tune, complaining of lost love in “Heartless,” and motherly love in “Coldest Winter.” As a critic, West can claim that he has ruffled the feathers of the last two American presidents, not to mention musicians and fashion designers as well—he overtly accused George W. Bush of not caring about black people after Hurricane Katrina, and was called a “jackass” by Barack Obama for literally stealing the spotlight from country singer Taylor Swift during her 2009 Video Music Awards acceptance speech.

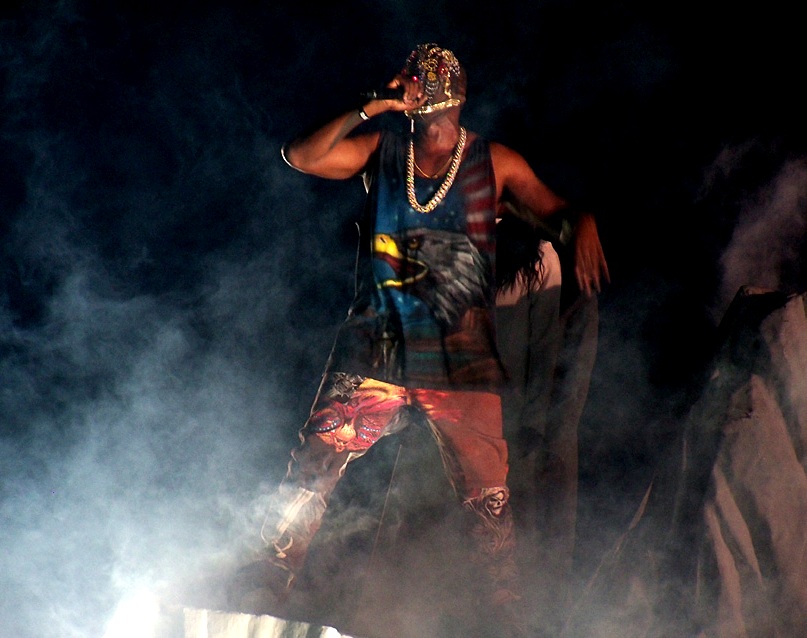

West relishes the platform his celebrity provides for his jabs at political correctness and takes every opportunity to throw a punch, even when he doesn’t know where it will land. His most recent stunt (Kanye would say he “popped a wheelie on the zeitgeist”) is a half-baked expropriation of the Confederate flag to promote his new album Yeezus. He was photographed last November in a green bomber jacket patched with a Confederate flag on the sleeve, and his tour merchandise offers tote bags printed with the rebel banner and t-shirts with the shadowed flag behind a yellowed skull between the obstinate all-caps motto “I AIN’T NEVER COMING DOWN.” As if the imagery wasn’t enough, West’s first single off Yeezus is entitled “New Slaves,” and its lyrics suggest—over a spare arrangement of muted bass, synthy organ, and heavy kick-drum—that the modern iteration of slavery is servitude to luxury brands, removing the idea of race from the power dynamic completely.

In an interview with Los Angeles’s 97.1 radio station, West explains (sort of) his convoluted reasoning for using the flag: “You know, the Confederate flag represented slavery, in a way—that’s my abstract take on what I know about it, right? So I made the song ‘New Slaves.’ So I took the Confederate flag and made it my flag. It’s my flag now! Now what are you gonna do?”

It would be nice to believe that Kanye West has the power to erase the loaded significance of the Confederate flag—that, by proudly draping the flag around his shoulders, he is able to expunge the violence that’s been perpetrated in its cause. But no one man can have all that power. “Critics make the world visible,” writes the political philosopher Michael Walzer in his 1988 book The Company of Critics, “they do not make it over.” By claiming the Confederate flag as his own and ignoring its history Kanye is unwittingly iterating the significance of the past, a past that is still flapping on flag poles in the Deep South.

Almost nowhere in America is the Confederate symbol’s tension felt greater than in the “Heart of Dixie”—my hometown, Montgomery, Alabama. In the city’s downtown center, two historical markers stand on opposite sides of the street, defining the South’s duality of oppression and activism: one marker signifies the site as the historical location of Montgomery’s slave auctions; the other indicates where Rosa Parks boarded the bus the day she famously refused to give up her seat in 1955. While the flag with which Kanye decorates his merchandise was never flown above plantations or slave auctions of the 19th century—the red rectangle with the white star-studded blue cross was never an official flag of the Confederate States of America, only a battle flag for the Army of Northern Virginia—it was certainly waved against the Civil Rights movement, when, many historians claim, the flag became the racially charged symbol it is today. In 1961, when the Freedom Riders rode into Montgomery after surviving a firebombing in Anniston and an attack in Birmingham, they were mobbed while taking refuge in a church less than two miles away from Rosa Parks’ bus stop. The Alabama National Guard was called to disperse the mob and protect the Riders, which they did by barring the doors of the church and trapping the Riders inside as tear gas poured into the church’s busted windows. The Guardsmen wore jackets with the Dixie flag stitched on the sleeves—fifty-two years before Kanye wore his in a Lamborghini.

The symbols and icons of the Old South still stand strong, regardless of West’s attempted expropriation. On a privately owned patch of land bordering I-65, the interstate that travels from Mobile to Chicago (home to Kanye West), a large Confederate flag flies today, waving above the same stretch of road between Birmingham and Montgomery that the Freedom Riders traversed a few decades ago. In the majority black city of Montgomery, the traditional public high school rivalry is between Robert E. Lee High School (named after the Southern Civil War general), and Jefferson Davis High School (after the Confederacy’s president). Both schools are severely underfunded and fraught with gang violence and racial tension–testaments to the Old South’s oppressive structure. In the early aughts, when Kanye strutted onto the rap scene with his pastel Polo collars popped, schools in Montgomery were forced to ban apparel featuring the Confederate flag after fights broke out due to the symbol’s spike in popularity with young white Southerners. They called it heritage; others called it hate. I wrote off any person who would wear such an obvious symbol of racism, and bounced to the rhythms of The College Dropout blaring in my headphones. Still, the flag is revered by defenders of the Old South and abhorred by those who fought for its demise.

The use of the Southern symbol of oppression on the Yeezus tour merchandise is a naïve attempt to rewrite history, to take the too-recent past and say that it’s no longer relevant. West, an artist whose roots are deep in the culture of hip-hop, somehow forgets—or more likely ignores—that his art’s tradition grew from a remembrance of the past, regardless of its horror. Literary critic and co-founder of n+1 Mark Greif argues in his 2011 essay “Learning to Rap” that “hip- hop has its memory intact. The gat a thug pulls from his waistband reawakens the Civil War and the Gatling gun. The skrilla that Southern rappers accumulate in 2011, cash money, remembers the scrip in which blacks were paid under the sharecropping system.”

The language of hip-hop harks back to the oppressed past from which it sprung, as does its imagery. Many rappers have paralleled the diamond encrusted bling often celebrated in hip-hop rhymes to refashioned slave chains. But these shining symbols signify wealth and success in spite of the confines of the past. Guns and gold turn the victims into victors.

West presumably feels that his co-optation of the Confederate flag is the same as the reappropriation of the word “nigger,” now “nigga.” The common defense of the word’s gratuitous presence in modern hip-hop is that black rappers have defanged the word by making it nearly meaningless in its ubiquity. Greif, however, argues that rappers’ use of the word initially acted as a “fail-safe” to keep white audiences from thoroughly engaging with the songs, and that the rap community felt that “if white America treated them like niggers, making life in the city jobless, service-less, abandoned, and hellish, why shouldn’t they announce it?” Perhaps this is what Kanye means to do with the Confederate flag, to announce to the world that the old idea of race-based slavery is dead, and that the “new slaves” are servants of luxury brands?

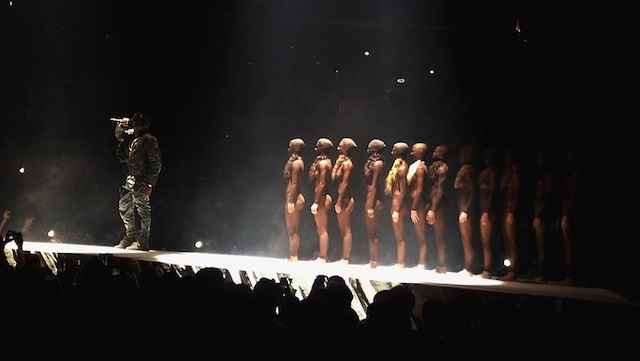

If we assume that this is West’s intention, what, then, does that make him—the wearer and seller of luxury brand products bearing the image of oppression? Hip-hop artists have always displayed their success through fashion, from Run DMC’s celebration of shell-toes in “My Adidas” to Jay Z’s song title shout-out to famed fashion designer Tom Ford, and Kanye has been a fashionisto from the start. But his use of the Southern stars and bars cuts deeper than mere fashion statement. By calling the Confederate flag his flag and by using it to sell his product, West aligns himself with the slaver, not the slave. He states just that in the hook on “New Slaves”: “You see there’s leaders and there’s followers, but I’d rather be a dick than a swallower.” West transposes the power dynamics of slavery into a sexual metaphor, acknowledging and aspiring to the selfish prickishness of those who hold power over others. He sells his Confederate flag-printed t-shirts to his multicultural fan base who become slaves to the Kanye West brand—they’re branded with his symbol, and bob their heads in agreement as Kanye claims divinity in custom-made Maison Martin Margiela masks during the spectacle of his Yeezus shows. I, too, bob my head to Kanye’s music, and often agree with his radical political positions. However, I do so with reservation, as I’m only willing to promote provocations that have purpose. Here though, Kanye seems to be poking without a point.

A certain amount of self-aware irony is inherent in Kanye’s actions, indicating his own complex understanding of his position. In “New Slaves” he explains the logic of racial profiling from the perspective of a retailer: “You see it’s broke nigga racism, that’s that ‘Don’t touch anything in the store.’ And there’s rich nigga racism, that’s that ‘Come here, please buy more. What you want, a Bentley, fur coat, and diamond chain? All you blacks want all the same things.’” Still, West makes a point of wearing his Confederate flag-patched jacket while shopping at Barney’s, the upscale department store that was accused of racial profiling last October. The irony muddies any assured meaning in West’s actions.

Perhaps West is doing the only thing he possibly can to separate himself from the symbol’s difficult historical associations. Others have struggled to define the position of the racially oppressed artist and come to similar conclusions. Ralph Ellison, author of Invisible Man, led a relatively privileged childhood despite being black in early 20th-century America, and consequently chose to align himself with white Modernists like T.S. Eliot as opposed to other black writers. But Irving Howe, a Jewish literary and political critic, stressed to Ellison the significance of the past’s effect on the present. In his 1963 essay “Black Boys and Native Sons,” Howe critiques Ellison’s dissociation from the black struggle and his willful ignorance of the inherent pressures put upon the black artist. “We do not make our circumstances; we can, at best, try to remake them,” he wrote, “and the arena of choice and action always proves to be a little narrower than we had supposed. One generation passes its limitations on to the next, black boys on to native sons.” Kanye claims to be a native son of American oppression—“New Slaves” opens with the acknowledgment that West’s “momma was raised in the era when/ clean water was only served to the fairer skin”—but, like Ellison, he sees his only escape in acting as if he is beyond them. If Ellison felt he could relate more to Eliot’s J. Alfred Prufrock than to his black contemporaries, then Kanye must feel more kin to fashion designer Alexander Wang than to those too poor to afford such luxury.

Kanye West’s celebrity and fortune puts him in a unique position to criticize the modern American power structure. Maybe he recognizes its rigidity, and instead of trying to topple it from below, chooses to tackle it from within. We know from his song “Spaceship” that he was once the token black employee at The Gap, and from his Yeezus era rants that he’s worked with (and been written off by) major fashion labels in the past. But by adopting the historic symbol of racial oppressors, he himself becomes one. When he sells plain white cotton t-shirts for $120 because they have “KANYE” printed (in white) on the inside collar, West is reaffirming his superior position above those fans that sustain him. In this self-serving success, West ignores the history of the structure he enjoys, just as he ignores the past of the symbol he employs on his Yeezus merchandise. The complexities of such obstinate denial echoes back to Ralph Ellison’s shifting ideas of the role of the black artist. In his 1964 essay “The World and the Jug,” Ellison reassures black readers that their struggles are not in vain and shouldn’t be forgotten. He writes, “Negro American consciousness is not a product…of a will to historical forgetfulness. It is a product of our memory, sustained and constantly reinforced by events, by our watchful waiting, and by our hopeful suspension of final judgment as to the meaning of our grievances.”

Kanye West should not attempt to rewrite history for his own transcendence; instead, he should attempt to acknowledge it for that of his fans.

As I drive south towards Montgomery and pass through the shadow of the Confederate flag that waves above, I can only laugh at the irony of the Yeezus merchandise. Because what else is there to do? Kanye West can try to make new meaning out of the bloodied banner, but it won’t wash the stain of racism away. That stain ain’t never coming out.

Some corrections and thoughts here:

Kanye first sped up soul samples on Hova’s “The Blueprint” in 2001, not “The College Dropout.” He was already well-regarded for his sampling technique prior to “TCD.”

And Kanye can be credited for a lot of things–he’ll be the first to remind you of them all!–but he didn’t “open” rap music to introspection. Biggie, Ghostface Killah, 2Pac, Mos Def, Common, Outkast, etc. did it first and better, at least compared to “808s,” which had good beats but overall isn’t Kanye’s best work. Also, auto-tune was nearing gimmick status when the album dropped in 2008. T-Pain had already rode that shit to death.

Brian, thanks for your comments. I chose to only focus on Kanye’s career in the public eye, so while you are right that he had been using sped-up samples in his production work with Roc artists like Jay-Z and Camron, it wasn’t until The College Dropout that Kanye moved out of the liner notes and into his own fame.

As to your second point about other rappers being introspective before 808’s, you are undoubtedly correct (and there’s no doubt in my mind that Kanye cannot compare to Biggie, Ghost, Andre, or Big Boi as a lyricist). But the difference between them and 808’s-era Kanye is Kanye’s willingness to be so openly sensitive and self-loathing, a vulnerability hardly seen in rap before the time. Perhaps I should have made that point more clearly.

I don’t know, man. Biggie’s “Ready to Die” is one of the most emotionally complex rap albums ever. He hates himself, wants to kill himself, fears someone is going to kill him, and just wants to make some money to feed his daughter. And sometimes loves it when you call him Big Poppa. RTD is wrought with contradictions and complications, the kind of shit Kanye turns into t-shirts. It’s probably clear I’m not a Yeezy fan. I was once back in his socially conscious phase before he was an auto-tuner, an art rapper, or whatever he’s on now with Yeezus and the Confederate flag.

BTW, Kanye aside, I did like your piece. It was a good essay that tried to make sense of hard shit using one of the most hardheaded rappers as a lens. Nicely done.

Pingback: Bitches, Pussy, Weed, Gold Chainz and Artistic Integrity | #HAROLDJOHNPADOR