I RECENTLY TRAVELED to Boston to attend AWP, a big writer’s conference. The trip was a luxury, since I operate on a limited budget of time and money, with two small children and a full-time job that’s only nominally related to the goings-on at a literary gathering. But writing is my passion, and I spent the weekend trying to cram in as much as I could, socializing, schmoozing, browsing the bookfair, checking out speakers. I had one more slot left before I had to catch my plane home, and I was deciding between two panels. One was called “How to Lose Friends and Alienate Loved Ones: Exploitation vs. Documentation in Creative Nonfiction.” The other was “Numbers Trouble: Editors and Writers Speak to VIDA’s Count,” which took as its starting point the now notorious statistics collected by VIDA, an organization devoted to women in the literary arts, that show how many high-profile literary publications disproportionately publish and review works written by men. The former panel dovetailed perfectly with my memoir-in-progress, but the 2012 VIDA statistics had just been released, and they highlighted how little change had taken place since the organization began making public the extent of the gender imbalance three years ago. VIDA’s stack of pie-chart infographics showing what a small slice of column inches women are getting roused me from a slumber, and I was ready to pay attention.

In the early 1990s, when I first started writing and with my women’s studies minor still fresh, I found myself counting bylines in the journals I read most often—Harper’s, The New York Times Book Review, and The New Yorker, for example—and I’d been shocked and outraged at what I’d found, at how many more male names appeared than female ones month after month. Partially in response to feeling closed out by the mainstream print community, as well as just generally underrepresented in culture at large, a friend and I started our own zine, Maxine, which we described as “a literate companion for churlish girls and rakish women.”

But over the years, my anger about the issue dulled. For one thing, to continue to feel shocked over something so perennial seemed naïve, uncool. What’d you think, little Missy, that things were fair? For another thing, well, I ceased counting. I felt like I should be moving on, and as I gained more confidence in myself, it was convenient to assume that things for women in general—at least writerly types— were moving along, too. That surely the world was heading in the right direction, however slowly, and that in the end strong writing—whatever that was—would win out. Look at Mary Gaitskill, Lorrie Moore, and Jeannette Winterson, who were all winning accolades for their searing female voices. The best thing for me to do, then, was hone my craft. Don’t we hear all the time that good manuscripts will always find a home, that good writers will find their audience if they just keep at it? To that end, not only did I quit counting bylines, I quit publishing the zine so I could focus on writing my novel.

And to be honest, another factor contributed to my shift of interest. The older I got, and the deeper into child rearing, the more my social circle expanded to include different types of people. I now knew many well-educated, relatively affluent women who had pulled way back on their professional and creative pursuits to focus on their families. Their numbers surprised me almost as much as the gender imbalance in bylines did. Because I met these women in the context of parenting, it was natural for us to talk about things in that sphere during the moments we spent together on doorsteps and at playgrounds, and sometimes those oft-interrupted conversations seemed narrow. Perhaps if gender roles in general had not shifted as much as I might have expected in my firebrand youth, women themselves might be more responsible for the lack of change than I had previously assumed. Could it be that there really were far fewer women producing work at the level to earn a place as either reviewer or reviewed in the New York Times Book Review? Even for me, a feminist who had studied and experienced the challenges of being a woman and a working mother in this culture, it was sometimes more comfortable–as well as more titillatingly iconoclast—to wonder if women were lamer than men when it came to cultural production than it was to acknowledge a deep-seated bias. Even for me, a left-leaning liberal with inclinations towards Marxist analysis, the rhetoric of personal responsibility had sunk in so deeply that I believed if things were still so off-balance twenty years after I first noticed gender imbalance in publishing that much of the fault must lie at my own doorstep, that of the Woman Writer. After all, had I pushed as hard as I could have with my own work, especially since becoming a mom? Wasn’t I making excuses if I complained that the paucity of reviews for the novel I eventually did publish had anything to do with my gender when we all know the literary landscape is tough for everyone and getting tougher all the time? Blame Amazon. Blame the Internet. Plenty of gender-neutral blame to go around.

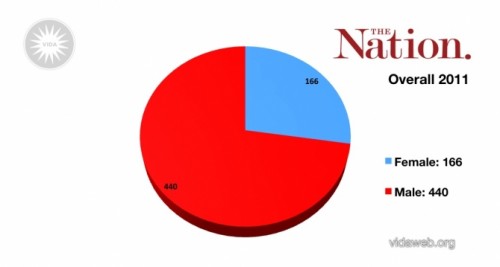

But when I looked at the VIDA infographics released this year, my attempts to buck up and buffer against the pain of systematic exclusion were blown away. Once again, I was shocked and dismayed. Yes, the issues behind these numbers are complicated, but the consistency of the statistics across publications and years shows the problem is ubiquitous, something permeating the culture that’s not going to be solved on an individual basis by women trying harder, and by a small percentage of them slipping through the gates. Thus, my urge toward the panel. I wanted to understand the problem better and contribute to the solution.

Or, well, apparently I did and I didn’t. Because, as I’ve said, that Saturday I found myself sitting in the basement of the convention center minutes before the session started still not quite ready to relinquish the creative nonfiction panel, which was of more immediate relevance to my current project. That’s mostly why I’d gone to the conference, after all. To get information and inspiration to improve my manuscript, the actual writing of which was already pushed to the edges of my life. Did I have to set it aside for something else once again? Did male writers feel pressure to spend writing time fighting political battles? My friend Martha Bayne was with me (as it happens, she’s the woman with whom I started the zine) and I said to her that if the full complexity of the VIDA issue was going to be addressed, that’s how I wanted to spend my last hour at AWP. But if the panelists were just going to lay out the facts for people who aren’t as familiar with them as I felt myself to be, then my time could be better spent elsewhere.

Martha nudged me toward the VIDA panel, and I’m glad she did, because my mind has been spinning since.

One of the comments by a panelist that most stuck with me was made by Katha Pollitt, the feminist columnist for The Nation and a role model of mine from way back. The Nation—despite being a voice of the progressive left, despite having several female columnists in addition to Katha Pollitt, as well as a female editor and publisher— has some pretty bad VIDA numbers. Pollitt acknowledged that the editorial staff had not addressed this adequately, but she also pointed out that the majority of women writers tend towards the same cluster of topics: pop culture, sex, relationships, family, feminism. She suggested that they’d have better luck finding a place in the front of the book if they branched out.

This was the kind of hard topic I wanted to see explored in a public forum. Just as I can get impatient with the domestic conversation in a room full of moms, I can grow drowsy when I read publications that deal exclusively with the issues Pollitt listed. And yet, I found myself feeling defensive. Because hey, what do you know: it turns out I mostly write about sex, relationships, family, and feminism (not so much about pop culture, although I did spent some serious time thinking about the Beyoncé halftime show). At Pollitt’s suggestion, I felt the urge to raise my hand and attest to my feminist bona fides: I read hard news! I treat my subjects rigorously! When I had my first baby, it was I who went back to work and my husband who quit his job and stayed home! Not that our arrangement meant we were living in conditions of a feminist or familial paradise, but, you know, we’re trying over here!

My defensiveness—the need for it, how quick I am to feel it, how likely representative of my gender I am in this regard—seems part of the problem. But isn’t a bigger part that subjects such as pop culture, sex, relationships, family, feminism—at least when tackled by women—are seen as gendered when they’re actually universal? And isn’t another problem that a female perspective on anything can be seen to preclude it from width while a male perspective is so assumed as to be invisible, often to men and women alike? Ack. As with the gender imbalance in bylines, I get tired of thinking about these things. I don’t want them to be true. Sometimes I can scarcely believe they are. I just want to write my manuscript in peace, my head in the sand where it’s nice and quiet! But in the last year when, say, elected officials have legislated about women’s bodies with a blithe ignorance of them, when editors who publish three times as many men than women continue to say things like they only thing they’re interested in is “getting the best reviews of the most important books,” it’s been particularly obvious that even for women like me who are privileged in many ways, being female remains a minority position.

Now, I know Katha Pollitt realizes all this, and that she was offering specific advice for freelance writers looking to places as many stories as possible in markets like The Nation. But the nonfiction writing I do outside of work is usually inspired less by ambition than by agitation. A question or comment will get under my skin, and I’ll alternate between obsessing about it and trying to ignore it, often because I don’t like the conclusions I’m drawing or the emotions it brings up. This conflict will knot up my mind until I am compelled to trace the path that caused the problem, to turn the thoughts and feelings into sentences until the strands run smooth. Issues related to feminism can have just this effect on me, because of how frustrating and confusing it can be to think and feel something that’s still so roundly disavowed in the wider world. Sexual violation is another common topic for me lately, as it’s a subject that’s similarly invisible and omnipresent, outrageous and commonplace, perpetuated and denied, seen as shopworn while still ravaging. Of course, men are subject to sex crimes, too, in roughly the inverse proportions to that which they’re interviewed in the Paris Review. But because the experience is seen as female, men can have an even harder time speaking up about it than women do, perpetuating the assumption of its gender specificity.

I’m aware that the subjects I’m writing about are likely to be seen as stereotypically feminine, no matter how I treat them, and that the audience for them might be limited. And still I persist. That to me feels like the feminist action in this case, rather than choosing a subject that’s going to have wider appeal in a news magazine. But of course, I make my living elsewhere; I write in the margins. I can’t be sure to what extent I arranged my life this way because the waters at the big-time venues felt so chilly from the start.

This brings me to a question I think about often, both specifically in regard to gender and more broadly. Where is the need for money an inspiration, and when is it hindrance? To what extent is a woman’s writing life shaped by whether she’s taken on traditional domestic and economic roles? E.J. Graff, a woman on the panel, described how she and her former female partner, both freelance writers, would goad each other on to “be the boy” and demand more money for their work because they needed to pay the mortgage. But when Alice Munro was asked in a recent New Yorker interview whether, essentially, men had it easier, she said: “Think if I’d had to support a family, in those early years of failure?”

I could wander a long way down this road, especially since the VIDA statistics were released around the same time as Sheryl Sandberg’s book Lean In: Women, Work, and the Desire to Lead has ignited the conversation about women and (mostly corporate) careers, but as it turns out, the VIDA numbers aren’t all that different in the publications that pay the (relatively) big money and those that pay mostly in prestige. Here’s a case where the discussion about the ways in which women do or don’t work at paying gigs is perhaps not all that relevant.

The day after I got home from Boston, I found myself beginning an essay inspired by the questions the panel raised, but after a couple late night hours into it, I paused and reconsidered. There’s been so much written about the VIDA count in the last month. Could I really add anything of value? And anyway, I was also itching to work on my memoir, and I didn’t know how I could find the time to get the essay done before the conference was too far past to keep my thoughts relevant. There were plenty of reasons put it aside.

When I caught myself thinking this way, I snorted. One of the points made by a member of the panel was that when editors call up women for op-ed pieces and tell them they need it the next day, the women often balk: they’re too busy getting dinner on the table or whatever, or they believe they need more time to research before making claims. Was I was pulling the same kind of duck-out move if I didn’t try to articulate my thoughts on this issue? I decided that I wasn’t. Not writing a piece that will pay a few cents in cultural capital if I’m lucky enough to get it run someplace other than my blog is different than turning down an invitation to write an opinion for the Boston Globe or whatever, right? And I have a job to attend to and children to raise and my own literary endeavor to pursue, and I know I can’t—as I’m oft reminded by the media—have it all. I have to make choices about how I use my time and energy. I have to be smart about it.

So I turned off my computer and watched an episode of Girls to unwind. The next day, I went into work and posted a Facebook status about the VIDA panel in lieu of continuing the essay. And that would have been that, except I got an email from an editor of this site encouraging me to write the piece and offering me a home for it. His interest made all the difference, and so here I am, crafting a narrative about my personal experience with the hopes that it can elucidate something bigger than me. I suspect this might be considered a female approach to inquiry, but when dealing with an issue—and there are many— where psychology and unexamined bias of both men and women play such a large role, it seems effective. How are we going to change things if we don’t examine the ways our own minds work?

Although the gender imbalance in bylines at the big venues hasn’t changed as much in the last twenty years as I once blindly hoped, one thing does seem different now. In the 90s, Martha and I had male friends who were supportive of our zine in various ways. They helped us haul boxes and offered us printing tips and DJ’d at our parties. But I couldn’t have imagined a man back then taking an active effort to publish work by women because he felt the female perspective was vital. Now, male editors like Matt Bell from The Collagist and Rob Spillman from Tin House are digging deep to figure out solutions to the problem. I’m almost embarrassed by how much this means to me. What, am I really just desperate to get approval from boys? My own gut sense of injustice wasn’t enough to keep me convinced that the status quo was whack (as we said in the 90s)? Even if there’s some truth to that, a co-ed response is validating and relieving. Mostly, though, I’m grateful for the women in VIDA who have worked so hard in such rigorous fashion to put these facts in front of the literary community for the past three years. By speaking out consistently, they’re making it less likely that women will swallow the shock and outrage, and that instead we can turn it into energy for change.

Pingback: PRESS RESPONSE TO “THE COUNT” | AMY KING'S ALIAS