Whenever fame claims another casualty, I wonder: could they have been saved? Could Elvis, Kurt Cobain, Amy Winehouse, Philip Seymour Hoffman, Heath Ledger, Jimi/Janis/Jim, et al, have been re-routed away from their death trip destinations?

“It was inevitable,” folks say. “It was going to happen one way or another.” This sounds like religious fundamentalism to me, often voiced, interestingly, by the non-religious. They dismiss an all-seeing God, yet in times of crisis they lean on notions of Fate, as if there exists a book of preordained events that cannot be altered. “There was nothing that could have been done.” Really?

Granted, entertaining that Magic If, invoking “coulda shoulda woulda” can be torturous. But I can’t help it, apparently, and because artists are my holy people, when one of them goes in an untimely fashion, I concoct an alternate narrative in which an outsider (someone on the margins, like me) disrupts the business-as-usual that will – and often does – end an artist’s life.

It goes like this: a person pure of heart, a Frodo unfazed by iron-willed parasites, by lucre, by fame, walks into a den of darkness and depravity, through scattered glassine baggies and ochre-colored ‘script bottles, and saves the day.

How refreshing would that be?

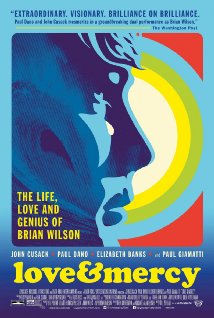

Go see for yourself with Love & Mercy, the new Brian Wilson biopic directed by Bill Pohlad. Although it’s only one facet of a unique, risky film, Love & Mercy takes on the “save the artist” narrative, and while it likely plays fast and loose with “the truth” – it is a Hollywood movie, after all, a story – it’s a great ride for those of us who like to put ourselves in the position of the caretaker, the sentinel, the advocate. The savior.

[I don’t feel the need to put up a spoiler alert because I’d wager if you’re going to see this movie, you know Brian Wilson, musical genius and co-founder of the Beach Boys, is still alive.]

Love & Mercy is a double narrative, switching back and forth from the mid-60s to the 80s. In the 60s scenes, Paul Dano (I smell Oscar nom) plays boy genius Brian on the brink of both mastery and madness; John Cusack portrays over medicated, hollowed-out, half-zombie 80s Brian, a man suffering from mental illness and under the sway of psychologist/Svengali/monster Eugene Landy, essayed brilliantly by the ever-reliable Paul Giamatti, here bewigged and mesmerizing.

Although the 60s scenes aren’t about being rescued, they are captivating, and they set the scene for the soul saving to follow. As a musician, I loved Dano’s twenty-two-year-old Brian bouncing exuberantly around an LA studio, working with top session players to bring his masterpiece Pet Sounds to life while the Beach Boys – Brian’s brothers Carl and Dennis, friend Al Jardine, and cousin Mike Love – tour with Brian’s on-the-road replacement, Bruce Johnston. (Due to his fragile mental health, Brian couldn’t handle touring.) The actual Pet Sounds sessions, of which much recorded between-song chatter survives, are legendary among music geeks, and the film version corresponds somewhat to how I imagine it was, a kind of pop music Big Bang from Brian Wilson’s fevered brain, an unknown-to-the-average-Joe cultural moment that would deeply influence Sgt. Pepper and thus, everything else. But sadly, as presented in the film, the Pet Sounds sessions, or the circumstances around them, also unhinge Brian. While he continues creating, including, with Mike Love, legendary post-Pet Sounds single “Good Vibrations,” and the even more baroque, ambitious (and aborted) album SMiLE, Brian succumbs to paralyzing anxiety and paranoia, exacerbated by LSD and PTSD from physical abuses suffered under his bitter, horrible, showbiz aspirant dad Murry Wilson.

The film skips over Brian’s much-documented descent into the torpor that rendered him a three-hundred-forty-pound, alcoholic, chain-smoking, drug addled recluse for much of the 70s, three years of which he spent in bed. (It is amazing he survived and emerged from this period.) All Brian’s loved ones feared for his life, and rightfully so. Brian’s first wife, Marilyn, with the blessings of the Beach Boys, hired edgy psychologist Eugene Landy to treat him.

So Landy did not drop out of the sky. To be fair, he made no bones about his methods, which included round-the-clock invasion of privacy and emotionally brutal confrontations, and he was somewhat famous for bullying addicts into sobriety. (Among his pre-Brian clients: Alice Cooper and actor Richard Harris.) After everyone signed off on this, Landy did, in fact, force Brian to lose a lot of weight. And he did probably save his life.

When we see Cusack’s Brian, all of the above has already happened, and Landy isn’t only Brian’s twenty-four-hour “therapist,” he’s his executive producer, business adviser, “financial consultant,” co-songwriter, dietician, yelling overlord, abusive dad replacement, and pill pusher. He has helped Brian become productive again, yes, but he’s also brainwashed him into thinking no one will ever love him if he doesn’t adhere to Landy’s dictums, and, as a judge ultimately will rule, he has exploited him. (Much of “the Landy years” have been documented, including this fascinating Rolling Stone feature.)

Enter the film’s hero: Melinda Ledbetter – here portrayed with slow-burn intensity by Elizabeth Banks. Melinda, a model-turned-Cadillac-saleswoman (this is LA we’re talking about) sells Brian a Cadillac. While Landy and his retinue watch (they are rarely away from their charge), Brian and Melinda have an offbeat conversation and sparks fly. Brian is an oddball, to say the least, but he is charming and magnetic. (Initially, Melinda doesn’t know who he is.) They go on some dates and have expository conversations.

Cusack and Dano’s performances are getting a lot of deserved attention, but Banks, as Melinda Ledbetter, is fantastic, albeit in a non-showboat-y way. Acting-wise, she does a lot of stealth heavy lifting. Her Melinda is the film’s moral engine, the prime catalyst for change. Reeling from a broken heart, she gradually realizes her nutty boyfriend is seriously mentally ill and in danger of losing himself completely, even possibly dying from Landy’s “cure.” (Brian is not initially forthcoming about his demons, but they rise, as demons do.) These realizations create a riveting kind of smolder in Melinda, part frustration, part anger, part desperation. She is our doppelganger, the most relatable person in the cast, the showbiz failure who just may see things clearer because of her outsider status. We wonder how she’ll act when called upon to do something inconvenient. Will she rationalize that her own efforts won’t amount to anything and life’s too short for this bullshit, and Brian, a lying hard case addict, is not worth the trouble? Or will she reject passivity, listen to her conscience, and follow through, standing up to these corrupt, willful assholes, even when her common sense is screaming no?

Cusack’s Brian, meanwhile, is a muddle of contradictory thoughts and actions; he knows he’s enslaved, yet the will that changed pop music forever cannot be engaged to free him from Landy. Pohlad and screenwriters Oren Moverman and Michael A. Lerner lay on the Freudian stuff pretty heavy, with Brian haunted by the hostile father he still wants to please; similarly hard-to-please Landy is a surrogate Nightmare Dad.

Melinda is initially cowed by all of this – who wouldn’t be? – and retreats from Landyville and Brian’s ever-apparent illness, made worse by Landy obtaining and enforcing Brian’s ingestion of copious meds. But she can’t stay away. Even after she and Brian break up, she attempts to engage the Wilson family in a rescue, but they are very put out with Brian, and initially reject her. She turns to Brian’s housekeeper, who ultimately finds incriminating evidence against Landy that will ultimately help disgrace him. (This actually happened, though not quite as portrayed in the film. Brian’s brother Carl was also instrumental in getting rid of Landy, and he is barely an entity in Love & Mercy.)

One unique aspect of Love & Mercy is its presentation of a battle royale between would-be saviors: Giamatti’s formidable Landy considers himself the savior, and he feels he should be lavishly compensated for being the only one who could help Brian, American Mozart, get out of bed, get healthy, and write songs again (co-credited to Landy). When Melinda finally challenges Landy, he sees a gold digger who doesn’t really care for Brian, doesn’t/can’t understand him; she’s a succubus who will recklessly lead Brian back into ill physical health and an untimely grave. He’s slimy and smart and plays on her insecurities, but she is tough. The air really crackles in the scenes between Banks and Giamatti.

Interestingly, in reality, it took Brian and Melinda a while to finally shake Landy. According to Google, Landy received approximately $430,000 a year from Wilson – that’s in 1980s dollars – for his “services,” which included “business advice,” even after the state of California revoked his license to practice psychotherapy due to malpractice charges brought against him by Brian’s brother Carl.

Clearly, one need not dig very deep to discover things likely did not go down as portrayed in Love & Mercy. But most of us know that already; biopics, like memoirs, while containing truthful elements and accurate data, are rarely “the truth.” What can and cannot be presented as “film fact” is territory lawyers stake and on which they fight, and for which they are paid Landy-esque sums, every day. (It amazed me when I found out how different “the Facebook story” was from The Social Network, which, nevertheless, is a great movie.) Does Love & Mercy get the gist of elements of Brian Wilson’s story? For the record, he and Melinda Ledbetter – she became his second wife and mother of their five kids – say yes. All other Wilson brothers are deceased, as is Landy, so they cannot weigh in. (Landy’s son, however, who spent a lot of time with Brian, has a lot to say.) Fellow Beach Boys Mike Love, Al Jardine, and Bruce Johnston have remained mum for now.

As to whether or not Landy was a real villain keeping Brian down: once an actual medical doctor determined Landy’s over-the-top psychotropic drug regimen had given Brian brain damage, the state of California not only revoked Landy’s license, they issued a restraining order so that he could have no contact with Brian. Soon thereafter, Brian’s surprise third act commenced in earnest. It continues to this day.

With legit medical help, Brian Wilson still writes, records, and actually tours. In the early aughts, he went back into the studio from which he’d fled in a psychotic fog forty years previously, and finished Pet Sounds’ follow-up, SMiLE, released as Brian Wilson’s Smile. This unclassifiable collection of pop majesty, with pastoral, often beautiful lyrics by fellow genius Van Dyke Parks, earned him his first solo Grammy in 2005. Just recently, he released his 11th solo album, No Pier Pressure.

~

I was lucky enough to catch Brian Wilson at the beginning of his upswing, when he and his collaborators presented Pet Sounds live at Radio City Music Hall around my birthday in 2001. This exists now as one of my last vibrant pre-September 11th memories, a crisp Manhattan evening when my wife and I witnessed a weathered music icon make his way back to the light in one of the most beautiful venues I’ve ever seen.

Still, watching Brian perform can be somewhat unnerving. He’s obviously damaged, eyes wide, hands shaking and seeming to move independent of his wishes, attendants gently guiding him from the shadows to the stage. But at the same time, his songs, swirling around him in breathtaking sonic clarity at Radio City, are perfect, and they find resonant spaces within where everything is temporarily OK. They do what they’ve always done for listeners, if not always for Brian: they transport, they send you to a timeless place of heart-swelling beauty for a few minutes. The juxtaposition of the music’s seamlessness and Brian’s brokenness stunned me. I knew then of Brian’s past, and I thought, “I can’t believe this man is still alive and here to share this art with us.”

It seemed miraculous, but of course it wasn’t. The truth, no matter how you slice it, is this: someone saved Brian Wilson. Who, exactly? Landy? Melinda? The housekeeper? Carl Wilson? The judge? All? Love & Mercy casts Melinda as the hero, and while it’s certainly not that simple, it doesn’t matter that much to me. I liked that my savior fantasy was at last fleshed out, because within that trope, a truth shimmers: once in a while, when a difficult artist is hellbent for the edge, seemingly bound for an early grave, surrounded by people who have either written him off or are manipulating him, he (or she) can be snatched from the brink and brought back to live more life, to breathe and work, wrangling pain into beauty.

Brian Wilson’s salvation, however it happened, feels like a victory for all of us. The artist –Brian in particular – is hope personified, and we need hope more than ever, to help get us through life. Love & Mercy illustrates that, but its real power is in showing the other side of a two-way street: Brian, one of our greatest artists, was the one who needed help, much more than we needed him, and hallelujah, he got it.

MR WARREN

Just stumbled over your review, which I enjoyed and agreed with—including your ‘real life’ observations and comments. In regards to your opening question, “Could they have been saved?” I want to suggest Lew Shiner’s GLIMPSES, a novel that addresses this question with what might be called American magical realism, even though it’s a time-travel fantasy. The protagonist attempts to run interference in the lives of Brian Wilson (in 1966), Jim Morrison, and Jimi Hendrix from his workroom in his house in 1993.

Keep on keepin’ on!

NEAL