i. The Ugly Truth and the Beautiful Lie

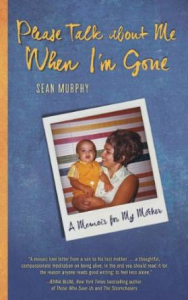

WHEN I PUBLISHED MY memoir Please Talk about Me When I’m Gone in 2013, I certainly was cognizant of the fact that I was, essentially, inviting strangers (as well as friends and family) to review intimate, occasionally embarrassing aspects of my life. But, when people enquired if I was especially concerned about this, I could reply with honesty that I wasn’t.

Writing such a personal account was, after all, a voluntary act, and it would seem more than a little disingenuous to protest too much about reactions to events and emotions I opted to disclose. Plus, one of the reasons I decided to write a memoir—a platform certainly more suited for celebrities or writers with a following—was because the material didn’t, or couldn’t, work appropriately as fiction. It was less a matter of accuracy (you either tell the truth or you don’t) than an issue of aesthetic (you either engage the reader or you can’t).

The project evolved as an anti-memoir of sorts, or at least a conscious rejoinder to the solipsistic stylizing that infested so many of the memoirs I’d read and found lacking. (This is not to imply I succeeded even in this modest objective.) Years earlier I’d jotted down something Washington Post book critic Jonathan Yardley—who tended to parcel out praise not unlike a disapproving parent—wrote while celebrating Neil Simon: “The autobiographical is meant to be a pathway to the universal rather than mere absorption in the personal.”

While he could be accused of being both cranky and quaint on occasion, Yardley was not only on-target here, he was prescient, making this observation before the ubiquity of blogs, social media and reality TV forever closed—or at least obfuscated—the gap between the personal and the public. Writers, I’ve found, have (increasingly) edged into self-indulgence, finding that fullest possible disclosure is a short-cut to earned insight or authentic connection. The defense “but it’s all true” might inoculate a memoirist in the most superficial ways, but mere truth is an inadequate approach, even for a work of non-fiction. (Of course, willful invention may appeal, at least initially, to more prurient readers, but is the strategy of a charlatan, as James Frey discovered.)

Despite my appetite for discretion (and, wherever possible, precision), I was not sufficiently prepared for the ambivalence my recollections tended to inspire amongst others whose experiences coincided, or clashed, with my perspective. Another quote, this one from Roger Angell, succinctly articulates what every honest writer won’t hesitate to acknowledge: “Memory is fiction, an anecdotal version of some scene or past event we need to store away for present or future use.”

Everything depicted in my memoir is true, but that does not necessarily mean everything I wrote is the truth. Being a recovered grad student with more than a few Cultural Studies classes under my belt, I come to the table with a predisposed appreciation for intent vs. execution, or interpretation vs. integrity, or ownership vs. textual authority, et cetera. For me, analyzing the myriad facets of creation, production and reception can be edifying, even imperative components of the reading—and writing—experience. As a writer, I am ultimately accountable to myself: so long as there’s an honest attempt to engage, avoiding sentimentality and cliché at all costs, the rest is in the hands of whoever picks up the book. This idea might torture or terrify a literary theorist, but I continue to find it remarkably liberating.

A less pretentious way of saying all this is simply to suggest that as long as a writer is satisfied, relatively speaking, it follows that by even allowing the material to be received by anonymous readers, it has already overcome, however tenuously, the author’s own doubts, insecurity, hysteria and windmill-tilting.

ii. Partly Truth, Partly Fiction

As I publish my novel Not To Mention a Nice Life, I find myself more, and not less, circumspect. This time around it’s not so much what I’m ostensibly revealing that makes me wary, but what prospective readers may, understandably, suspect or suppose.

Which isn’t to say I’m unduly concerned; when you write fiction employing a first person narrator who is roughly your age, ethnicity, etc., you are all but provoking—even daring—people to assume you’re writing about yourself. (Generally speaking, the more obviously the writer wants the audience to associate the protagonist and himself, the more insufferable and lifeless the prose is likely to be.)

Then, of course, there’s the fact that novels are not-so-thinly disguised delivery devices for the author’s own obsessions and ideas. Aren’t they? No, not really or, at least, it’s seldom so straightforward. But that won’t stop readers from drawing certain conclusions. In any event, don’t feel sorry for a misunderstood scribbler, no one is compelling them to put their stories—real or imagined—into the proverbial court of public opinion. (Generally speaking, the more noble or lovable a protagonist that may coincidentally be confused with the author is, the less trustworthy and insecure the human writing the book is likely to be.)

On one hand, it’s difficult to deny the accuracy of this observation by David Foster Wallace: “Writing fiction becomes a way to go deep inside yourself and illuminate precisely the stuff you don’t want to see or let anyone else see, and this stuff usually turns out (paradoxically) to be precisely the stuff all writers and readers everywhere share and respond to.”

On the other hand, Tim O’Brien—who, incidentally, has mastered both fiction and memoir—speaks with unassailable authority when he asserts “by telling stories, you objectify your own experience. You separate it from yourself. You pin down certain truths. You make up others.”

A memoirist can invoke this explanation to illuminate, or justify passages that don’t mesh accurately—or comfortably—with someone else’s memories. A novelist cannot use the same shield, especially since fiction is, after all, entirely invented. Right?

“I want you to feel what I felt,” O’Brien writes, addressing the reader (the audacity!) in his story “Good Form”. “I want you to know why story-truth is truer sometimes than happening-truth.”

One of the reasons The Things They Carried is such a singular, innovative work is that it skirts the unconventional even as it circles around itself, explicitly attentive to the traditional. O’Brien was one of the first, or at least most successful seekers of a new way to interrogate the always uncertain intersection of memory and truth. His authorial stance broke through the postmodern haze, updating Kundera’s undaunted intruder and Vonnegut’s awkward interloper, conceiving an honesty that is at once self-aware and unvarnished. It’s the voice of the writer, yes, but more, the voice of the writing; the words between the written lines.

Speaking personally, and with appreciation, O’Brien helped me to filter and, at times, repurpose the creative and intellectual circles literary criticism had me spinning inside, during some tentative years when theory and deconstruction usurped much of the adventure and serene uncertainty fiction requires. If sober retention can’t be trusted and there’s no such thing as Truth, memoirs are illusions and novels are nihilism.

iii. Good Form

Take a guy. Let’s say he’s about my age: old enough to own his own condo and pay almost all his bills, who is young enough to be unmarried but old enough to understand he is not getting any younger. Add a fresh dose of alienation—not enough to be unhealthy, of course, but enough to enable him to function in a world full of a-holes, imbecility and indifference. Take this guy and provide just enough stability so that there are no excuses, but plenty of alibis. Maybe he’s estranged from too many old friends, or aggrieved about an absent parent, or perhaps he is just emerging from the wreckage of a ruined relationship or, probably, he is utterly average in every regard, except for the uncomfortable fact that, unlike almost everyone else he knows, he is aware of it. He would love to mix things up and instigate some excitement into his own humble narrative. Unfortunately, a fight scene is not feasible, a car chase is getting too carried away, and a love interest appears to be out of the question. Also, he has to be awake and ready to work in the morning, just like everyone else.

And, he thinks: you’ll never be that guy. The guy who sits on toilet seats without a second thought; who might use the restroom half a dozen times a day and look at himself in the mirror once, or twice, tops; who actually doesn’t mind—or, perhaps, secretly prefers—lukewarm coffee (or, worse, decaf, or, worst, the kind served over ice for five bucks and change); who can eat bologna sandwiches and avoid meat (even bologna) on Fridays during Lent; who believes that God blesses America and that Jesus Christ is a capitalist; who can relate to anyone playing or providing commentary on a game of golf; who buys clothes—or food, or appliances, or fiancées for that matter—from a catalog; who is actually entertained by movies, or books, or albums, or people that put entertainment before aesthetic, or amusement before honesty; or sales before soul. You’ll never, in short, be a normal person.

None of that actually happened, but it’s the truth.

All of that is the truth. None of it ever happened.

(Anthony Burgess: “It is the novelist’s innate cowardice that makes him depute to imaginary personalities the sins that he is too cautious to commit for himself.”

Which is not to insinuate there are any discernible acts of derring-do in my novel. There aren’t even many acts of derring-don’t, though there is certainly plenty of derring-dumb.)

That’s my story. But that’s not me.

Maybe it’s also your story. And that’s the whole point.

Isn’t it?

(Sean Murphy is an associate editor for The Weeklings; his novel Not To Mention a Nice Life publishes today. More info here.)

Pingback: Death of a Salesman and the American Dream - Murphy's Law

Pingback: Death of a Salesman and the American Dream (Revisited) - Murphy's Law

Pingback: Murphy’s Laws: 53 Infallible Observations on the Occasion of Turning 53 | Murphy's Law

Pingback: Unsolicited Press: Q&A with Sean Murphy - Murphy's Law