I STILL HAVE HANGOVERS, thank God.

Everyone who has known an alcoholic knows that as soon as you stop feeling the pain, it’s because you are no longer feeling the pain; you are no longer feeling much of anything.

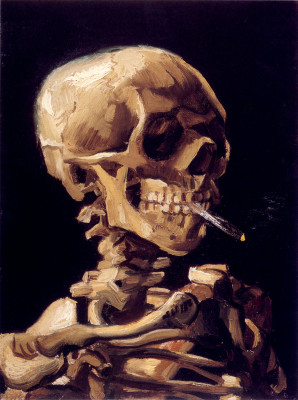

So, I welcome the horrors of the digital cock crowing in my ear at an uncalled for hour, am grateful for the flaming phlegm in my throat, the snakes chasing their tails through my sinuses, the smoke stuck behind my eyelids, the shards of glass in my gut, and the special ring of hell circling my head. Because if it weren’t for those handful of my least favorite things, I’d know I had some serious problems.

All of us can think of a friend whose father (or mother for that matter), we came to understand, was in an entirely different league when it came to the science of cirrhosis. The man who falls asleep fully clothed with a snifter balanced over his balls, then up and out the door before sunrise—like the rest of the inverted vampires who do their dirty work during the day in three piece suits. Maybe it was a martini at lunch, or several cigarettes an hour to take the edge off. Whatever it was, whatever it took, they always made it out, and they always came back, for the family and to the refrigerator, filled with the best friends anyone can afford.

Our friends’ fathers came of age in the bad old days that fight it out, for posterity, in the pages of books, uneasy memories and the wishful thinking of TV reruns: the ‘50s. These are men who have never opened a bottle of wine and have no use for imported beer, men who actually have rye in their liquor cabinets—who still have liquor cabinets for that matter. These are men who were raised by men that never considered church or sick-days optional, and the only thing they disliked more than strangers was their neighbors. Men who didn’t believe in diseases and didn’t drink to escape so much as to remind themselves exactly what they never had a chance to become.

Theirs was an alcoholism that did not involve happy hours and karaoke contests; theirs was a sit down with the radio and a whiskey sour, a refill with dinner and one before, during and after the ballgame. Or maybe they’d mow the lawn to liven things up, tinker under the hood of a car that had decades to go before it could become a classic. Or perhaps friends would come over to play cards. Sometimes a second bottle would get broken out. This was a slow burn of similar nights: stiff upper lips, the sun setting on boys playing baseball, mothers sitting on the couch watching TVs families did not yet own, of forced smiles battling bottled tears in the bottom of a coffee mug, of amphetamines and affairs, overhead fans and undernourished kids, of evening papers and a creeping conviction that there is no God, of poets unable to make art out of the mess they’d made of their lives.

It was a hard time where people did not live happily ever after, if they ever lived at all. It was a time, in other words, not unlike our own.

***

When I lucked into my first so-called real job I got in the habit of referring to the time—admittedly too long—spent in the service industry as the bad old days. It wasn’t because I had no fun (I did) or that I thought there was any future in it (I didn’t). It wasn’t that I felt joining the corporate world (grad students and waiters refer to it as the real world) was any type of instant ticket to peace or fulfillment. But it did remove one from the front lines of a scene with too many lives on the fast track to nowhere. Most people there fail to understand where they are, and where they are not going.

And when I think of the place some people never find a way to leave, it makes me remember one person in particular. More than the implicit slights suffered or the stalled potential each day I strapped on an apron, when I think about what I could never afford to lose, I think of Izzy. That, of course, was not his real name, but it was what everyone called him. When he and I first met I would have sworn he was in his forties, but in fact he had only recently turned mid-thirty-something. Not old in the nine-to-five arena but ancient in the restaurant business. A lifer who had never been promoted to general manager, he was a satellite drifting through the soiled orbit of a franchised business. He was never handed his own place to run, and he seemed entirely satisfied with that arrangement. In fact, as I came to see for myself, he counted on being an assistant behind the scenes, the hardened soldier who could close up shop and count the checks. We were often the last two left, hours after the final customer had called a cab or rolled the DWI dice. After a shift that started at 4 PM Izzy would set up camp in the sweltering office in the back of the kitchen, going about the unexciting but excuses-free business of book-keeping.

When Izzy showed up for his shift the following afternoon he always looked like someone had scraped him off the bottom of a greasy skillet. Red eyes blurred, his neck shrieking in silent agony from the burn of a blunt razor, the cigarettes and coffee escaping in sluggish waves from every inch of his sagging skin. Head bowed not in deference but disdain of the daylight; he could scarcely formulate the words being signaled from bruised brain to long-suffering lips. He would step up to the bar, shake his head and ask me to call him an ambulance. Then he’d disappear into the men’s room for a minute or two, emerging like a televangelist with a badly ironed shirt. He could barely tie his shoe, but after his magic act in the crapper he would be ready to plate a thousand entrees and run laps around the building in his wingtips (managers who wear comfortable shoes are never taken seriously, but they don’t realize until it’s too late it’s not because of the shoes).

For the next eight-to-ten hours, in between return trips to the powder room (occasionally he may have even used the toilet), Izzy was constant, awkward motion. All the waiters were in awe of him and all the waitresses were repulsed by him (especially the ones he had slept with). Izzy could sweat out more alcohol in a single shift than most of us could drink in an entire weekend, and he never missed a day of work during the two years I knew him. Even if you didn’t catch him ducking into the bathroom you always knew he had recently refueled because he would suck his teeth like someone trying to extract snake venom. The lip smacking and teeth licking were, to me, the black and blue collar stage of development between rock star and burnout, the line so many in the service industry straddle before they get out or go under.

None of this fazed me, which isn’t to say it was not unsettling, but grunts in the trench don’t offer advice to their sergeants, so I mainly focused on my own unsavory habits. But I could never figure out how Izzy, when he retreated to the office each night to match receipts, guest checks and time sheets, was able to polish off an entire bottle of peppermint schnapps. When he finally went home, closer to sunrise than midnight, that bottle he took back with him would always be empty. At first I figured he was trying to impress or even intimidate me (full success on both fronts), but after months of the same scenario, I had no choice but to acknowledge that his appetites and obsessions had, at some point, evolved from unhealthy to superhuman. That bottle was not something he wanted, and was no longer something he needed; it was simply something that he required, along with the bathroom breaks and the air his lungs inhaled. I worked dozens of shifts where I didn’t see him eat a scrap of food, but he never went into that office without his bottle of schnapps. And at least once a week he’d arrive at work with fresh bottles he kept to stock the bar. I could never fathom the physics, or biology (or algebra) that enabled a man to drain a fifth each evening and still function, but I also learned the hard way in high school that some subjects would, for me, remain forever mysterious.

By the time he took his transfer to the next location (never a demotion but never an advancement) he looked like he could collect social security. How long can that lifestyle sustain itself? I asked myself, then, and ponder it now. Where is Izzy today? Is he in an assisted living facility somewhere, or at the bottom of a river? Will I find him patrolling an intersection one night, not embarrassed to ask for tips after all these years? Or did he take the hard way out and start a family; his bad habits replaced by baby bottles, dirty diapers and manicured lawns? Or most likely and equally unsettling: has he subscribed to an altogether different sort of salvation, whacked out of his skull with sobriety?