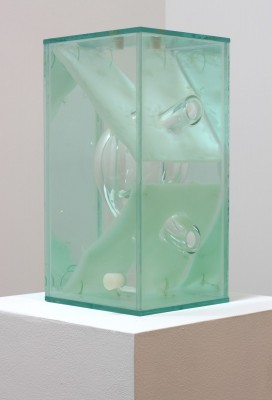

TAKE A TRIP down Orchard Street in New York City, and there in what was once a clothing store now the art gallery, On Stellar Rays, you will see a plate glass window with five glass boxes. Within each are substances that appear to be tissue, flesh and blood and other liquids hard to contemplate for their bodily suggestiveness. The glass cubes grow membranes, fleshy organs either pink or a pale unearthly color, as if something of us were expressed in them. The contents seem both alien and physical filled, possibly, with test tube meats, those ones that promise to grow beef or genetically-modified fish.

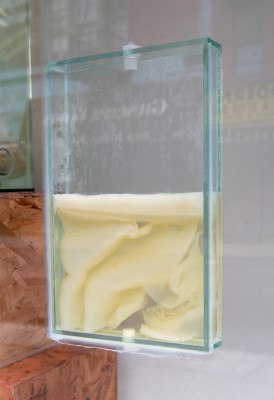

Jennifer Sirey, “Mother” detail, glass, bacteria, water, vinegar, 2013. All images courtesy of the artist

Bulbous glass protrudes into the planes and adhered directly to the window. With a quality somewhere between alien and birth or even Cronenberg’s rarely-scene classic on motherhood, The Brood, the glass bladders displace the tanks’ liquid and create a physicality that breaks their rigid geometries. Suspended glass on glass, they are a metaphor riffing on the storefront window as well as classic minimalism.

This doubling of glass on glass, windows within windows, is the work of sculptor Jennifer Sirey. She grows bacteria, creating a duality between her materials and display that pushes between poles as extreme as industrial and corporeal, glass and flesh, two-dimensional and three, while the contents suggest menstrual flows and birth. There’s something so decidedly womanly in those cubes that the very thought makes me uncomfortable. To be a critic and left with such reductive language as “feminine,” say, or “masculine” seems a failure of words. Yet such words are suggested in the tug between Sirey’s hard-edged vitrines and the soft tissue contained within. There’s also something self-exposing in her work, a Courtney-Love-like pretty on the inside, of a woman ripping out her guts and saying, “You want pretty, well, take this. That’s pretty for you.” The pink of Barbie turns into the color of raw flesh.

In another show early this spring on the Lower East Side at Feature, her piece “Three Holes” made manifest its subject in title alone. Still, there’s a grace to the work, a formal beauty, with the edges twisting and morphing – suspended in space. Even her “Sail,” where the monofilament stitches roughly suture together the membrane, is delicate with the blown glass adding a fragility to the piece. Looking at it makes me think of that other artist who has worked with tanks and biology; that would be Damian Hirst with his sharks and lambs suspended in formaldehyde. In comparison to Sirey his seem like a cheap joke – an easy one-liner on life and death.

In this our age of virulence and science, where stem cells and biology are both tools of terror and possibility, her work seems apt. It also plays off minimalism, that last great gasp of modernism. Taking the serial object as subject, minimalism’s artists displayed industrial materials as the thing itself, taking abstraction to its teleological end. Looking at Sirey though makes me think of what critic Kay Larsen wrote in New York magazine in 1993 (more than two decades after minimalism’s moment): “You need to know that women resented minimalism’s formal perfection because it allowed them no space for their private lives.” Now 40 years on, here is Sirey shouting back an answer, and it’s impossible to see her work and not think of Eva Hesse. She stands over art today as a bit of a patron saint, and her work has a visceral materiality. She gave a physicality to minimalism’s cubes and worked with latex and fiberglass casting them in organic shapes that had an uncomfortable pregnancy. Indeed Sirey’s work has been called in Art Forum, that high-bound journal of contemporary art: “A lost Seventies-feminist classic.”

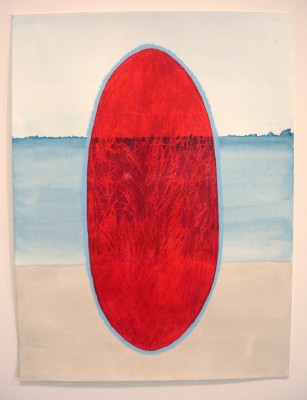

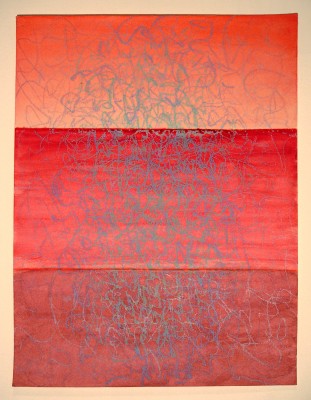

To make her pieces, she begins with a schematic at three-quarters scale. The process is rigid and precise requiring her to plan out the membrane and the exact dimensions of her glass tank. “Like growing a ship in a bottle,” Sirey has described it. Flattened out, the schematics read as a dissection of the sculpture. Lately she’s been turning them into abstract landscapes that bear a similarity to her earliest experiments with seascapes, painting and abstraction. Now her work brings these threads together. She takes elements that are out of fashion: landscape and abstraction and painting and puts them in two and three dimensions to give them vitality.

These transformed schematics have the haunting quality of a Forrest Bess painting. His work too seems an apt comparison with his pained relationship to gender and attempts (themselves troubling to consider in depth) of mutilation and emasculation and self-castration – which he did, in fact, perform). He believed it would make him eternal. The experiments probably helped kill him (he died in 1977) but through the paintings that resulted, he probably will live on forever. He too towers as a beacon over art today. This struggle with gender and the body is present in Sirey’s work, though not pulled to such extremes. You can read in her work narratives about exposure and sexuality, rape and questions about what it means to be a woman.

~

She started working with bacteria and fermentation accidentally a couple decades ago. It grew on algae she had in a piece, but she’d always been interested in decay and process. She’s used milk and blood and rust before she hit her métier, her material, acetobacter, the bacteria that ferments wine to vinegar. The bacteria spreads across the wine and adheres to the geometry of the container in which it grows. Rather poetically and evocatively the bacteria is also called “mother of vinegar.”

Her early work had vinyl tubing supplying oxygen to grow algae in seven-foot tanks and test tubes with different liquids and magnets floating and sinking in water and oil creating a chain from the top to bottom of a six-foot column. She set grapes to ferment in jars suspended in liquid. Each piece was its own system, with its own laws following (or failing at) a set of processes.

Now acetobacter, that mother of vinegar, is promoted in these days of kombucha and Brooklyn home-brewing for its healthful qualities. Back in 1993, however, when she first happened on the substance, she had to research it to figure out just what it was. Then, there were no vinegar bars, no fermentation freaks, no one talking about “SCOBY,” that is a Symbiotic Colony of Bacteria and Yeast. She’d kept hers alive for two decades until Hurricane Sandy hit her Red Hook studio. Afterwards she went on a hunt for a new mother, “mother” being the name of the host bacteria as well as the name for her piece at On Stellar Rays.

In her studio you can see the process at work. The cramped spaces suggest home chemistry experiments, more mad-scientist-in-her-garage than white lab coat. Space heaters are covered in plastic sheeting beneath which her constructed tanks are tipped on their sides, balancing precariously as she grows the bacteria in red wine or sake into the plane and shape she’s after. The whole apparatus has to stay at 85 degrees. Should things go wrong, the temperature be off; the acetobacter will die. Mold will grow and spread and kill her bacteria.

When Sirey is done fermenting, she pours out the red wine. The very process sounds like menstruation or birth. The liquid passes through a small hole in the bottom of her vitrine. Bits of bacteria can slip out, and it has a fleshy quality like a clot. The bloody mess of wine and water spills into a five-gallon bucket as she replaces the wine with water to hold the sculpture stable. It will live forever. With no air inside, the piece remains in a suspended state.

Sirey studied biology and architecture before painting and draws on these in her work as well as on mathematics. The installation at On Stellar Rays riffs on the fibonacci sequence. It’s her own math geek joke about the golden mean and the perfect proportions of beauty and classicism. There are references too like the Invisible Woman toy her father got her when she was in 5th grade. The toy’s plastic anatomy and clear plastic skin let you see through the layers of translucent muscle and organs. In talking about her work she mentions notions of attraction and repulsion, and the window installation has a can’t-help-but-stare quality. Her pieces recall that cliché girls are taught about beauty being on the inside as if to reassure them about their looks or looks in general. When she was little, Sirey took the saying literally, wondering if you stripped off the skin, what would be beautiful inside? Now the very bodily nature of her work reinvigorates figurative sculpture, finding a way forward for the tradition today.

There is another story to Sirey’s work, the story of the unknown, moments lost, careers sacrificed. Eva Hesse, patron saint for the quality of her art and her bravery, struggled in her marriage to another artist and with questions of fame and her place in the art world and making art that mattered. She wrote about them frequently in her journals. Cut down too young, she died in 1970 at 34. Part of the myth of her life was that her experiments with materials that made her art so profoundly beautiful killed her. The fiberglass and latex and resins supposedly led to her brain tumor. So much of the narrative of women’s art has been the cut-down young, unknown, unrecognized, with careers abandoned or given over, whether for kids or for men. For the husbands and their careers – their careers as artists. The list of such women is painfully long, often the flip side of modern art. Sirey has been quietly, diligently making this work for nearly two decades. You now have seven days left to see it in all its disturbing beauty and grace.