IT HAS BEEN SAID that we are living through a new renaissance of thought, and one that is powered by science. That is real science based on testable ideas and rigorous peer group assessment, not science that has been hijacked by vested interests; that is science that seeks only to get to demonstrable truths, not science that has been co-opted and skewed in the interests of making profit. Whilst we can never be sure that we are part of a periodization of history when we are actually in it, it does feel like there is a quiet revolution going on, and one where science has become part of culture, and part of our daily lives, rather than apart from it.

Science and art have two things in common—firstly, in that the seed of an idea begins in the human imagination. A scientist creates a theory or a model of how something works and then tests it, and then proves or disproves it, or more likely has to refine the theory and try something else, which then may or may not stand the test of empirical investigation. As artists and writers we examine the human condition by going deep into our imagination. We appeal to the subconscious brain and to the humanness that binds us all, to try and create work that addresses our turmoil. We undergo a process of trial and error creating, re-imagining, re-working until the piece feels right, but unlike the scientist we do not expect any solid answers. We know we cannot solve the dilemma of existence, but we hope our work expresses some emotion and feeling that somehow connects with someone at some level.

The second thing which binds science and art is that they are both open to all. In the introduction to Science is Culture—Conversations at the New Intersection of Science and Society (2010), editor Adam Bly reminds us that: “Science is necessarily flat and open. Any idea can be overturned by anyone at anytime.” A piece of art is open to the interpretation of the beholder. She may see something in it that the artist never intended, or in agreement or dissent with the artist she may just think it is a piece of crap.

Like music or art, science is not something that we are separated from simply because we have not achieved the required academic proficiency. Science is an idea not an ideology, it is an open way of looking at things, that is rooted in reality. There is science in the way we choose our friends and partners, and there is science in the community effort to understand our world and our place in it. The scientific method in us is even part instinctive—we test things out and if something or someone repeatedly does not work for us, we find something or someone who works better for us.

Our imagination and the capability of our brains for abstract thought makes us all artists and scientists to some degree. This is how our minds work as children, experimenting through our play to make art and also in instinctively practicing the scientific method and discovering things for ourselves, and later measuring our own experience with the experience of others. We all know that fire is hot, because we all once burned our fingers by getting too close. This scientific proof remains testable and demonstrable. In fact, when we were young we all repeated that experiment, conducted by every last one of our ancestors all the way back through deep history to the time even before abstract thinking.

And, in being able to reflect upon the idea that fire was hot, and finding the cooked meat and roasted seeds that were left in the wake of forest fires caused by lightning storms, our ancestors, step by tiny step, leap by great leap, evolved a methodology by trial and error to tame and master fire.

Today in the early twenty first century we seem to be on the verge of losing our mastery of fire. The culture of science is the communal endeavor that stands between us, and the extermination of our habitable environment, which is continuing at a rapidly accelerating pace, at its most virulent, in the form of man-made global warming. The most peer reviewed and tested science in history, in the form of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, has been telling us this for a quarter of a century.

June 24, 2013, will mark the 25th anniversary of James E. Hansen’s landmark report to Congress that: ”It is time to stop waffling so much and say that the evidence is pretty strong (99 per cent) that the greenhouse effect is here.” The theory that advanced capitalism is failing us as human beings, has been tested and proven over and over, telling us that we need a new working method of how to organize our lives. What we know of deep evolutionary history tells us that as basic survival becomes an everyday concern for more and more people on this planet, then cultural and maybe even genetic evolution will intervene, and in that, there is no guarantee that homo sapiens will continue to inherit the earth.

Scientific advances, especially during the last two decades—from being able to map the human genome to being able to see in detail which regions of the brain are engaged in which activities; from uncovering more remains of species ancestral to us, to understanding better how evolution works; plus a myriad of cross-disciplinary advances—bring us closer to answering the question of who we are and where we come from. Being part of this scientific debate, and understanding just how fragile our existence is, really may be of lasting value to us and our children.

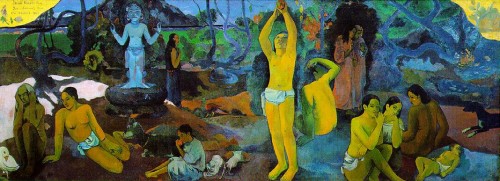

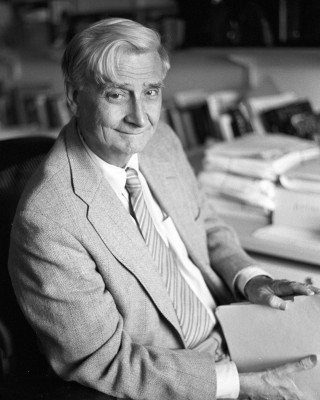

Based on a lifetime of pioneering research, E.O. Wilson, in his latest book The Social Conquest of Earth (2012), alluding to Paul Gauguin’s painting Where do we come from? What are we? Where Are we going?, makes a convincing argument that we are who we are—a social species with the powers of abstract thought and language—because at every turn our ancestors made the correct sequence of lucky adaptational guesses over millions of years in the evolutionary maze. Further, he identifies the biological origins of our human condition today as arising from our deep history of multi-level selection: that “inevitable clash of individual selection and group selection” within us all, whereby the evolutionary selfishness to promote one’s own genes, is pitted against the altruistic instinct to serve the group, and in so doing extend the chances of one’s own offspring surviving.

Today our strong urges to bond with a significant other is in contradiction with our different urges to make good with our genes with other lovers. Quite possibly our subconscious brain is making two sets of chemicals that are in competition with each other, to steer us one way or the other, or both, whilst our conscious mind wrestles with the possibilities, over-ruling one faction or not? Speculating, had Hunter man A not bunked off from the hunt to make love to Gatherer women B from the rival band, just as Hunter man B was swinging by Gatherer woman A’s encampment to do the same, then maybe homo sapiens would not have had the same reproductive success that we have had, and maybe you or I might not be here today.

But survive we did, and spectacularly so, by being neither completely free of our deep history, nor completely bound by it. The human nature we have inherited, based on hundreds of thousands of years of prior genetic and cultural experimentation, influences but does not dictate how we use our brain power or how we behave today. We make choices, but science reveals because of our human nature they are not always rational choices.

Wilson goes on to say that “in summary, the human condition is an endemic turmoil rooted in the evolutionary processes that created us. The worst in our nature coexists with the best, and so it will ever be. To scrub it out, if such were possible, would make us less than human. ” And, that “much of culture, including especially the creative arts” arises from, and is preoccupied with, this unresolvable contradiction of multi-level selection. This has been expressed in its simplest form in the story of having an Angel on one shoulder and the Devil on the other. To complicate matters, the scientist in us knows, counter-intuitively, that not all selfishness is bad, nor all altruism good. The grey matter of our brains evolved as the definitive grey area.

That said, the cultural evolution of storytelling has been very important to our survival. Animals play, which means play predates human culture, but armed with a brain capable of imagination our ancestors found new ways to play, resulting in no particular order in the development of language, song, jokes, humor and storytelling that comes from being a highly intelligent social species. Maybe we evolved storytelling and art because there is simply no way to solve the paradox of our condition, but we had to find some balance between basic survival and double edged sword of a brain unleashed, or put more simply, the brain, like the body, needs a healthy amount of exercise to stop it from degrading.

We also evolved religion because it benefited the survival of the group. Wilson goes as far as to say that “the creation myth is a Darwinian device for survival.” Religion probably evolved because, in the real world of surviving, having a set of answers to unresolvable dilemmas helped bind the group together. A creation myth gives the reassurance of being part of the group, uniting the group, and conferring the status on the group of being the chosen people. This was essential to survival, because the group was in competition with other groups. The rival groups in competition for food and water resources invaded each others’ territories, and whichever group had the stronger unifying bonds, whoever worked together best as a group, defeated the rival. Perhaps one reason our Homo sapiens ancestors defeated our rival Homo neanderthalensis is because their co-operative and communicative skills, reflected in their advanced religious glue, gave them the competitive edge.

Stories remind us that we are human, from Shakespeare to soap opera, reflecting the drama of our human condition. To be monogamous, or not to be monogamous? To be the leader who unites the group to the detriment of the traitor or to be the lone individual defying the group to bring about change to the group? To exact revenge, or to show mercy? You have heard them all.

Maybe stories evolved to give us comfort, to help baby go to sleep, and to remind us that along with struggle there is great joy in life? Depending on our frame of mind, the stories with the fairy tale endings give us falsely reassuring comfort that it all works out in the end, except when it doesn’t, because sometimes it won’t —borrowing from the Dr. Seuss’s Oh, The Places You’ll Go. Interesting storytelling and stimulating art may lead to the discovery of a truth in art, but the art poses more questions than it answers. The same goes for science in that in its logical beauty in uncovering some answers, it reveals a whole host of previously unasked questions and wholly new mysteries that fire our imaginations.

Homo sapiens have survived so well because so far, on the whole, we have proven to be great problem solvers, inventing art, the food of the soul, to keep our free-wheeling brains happy, just as we invented the more practical tools of survival. Stone tools evolved from conveniently shaped naturally occurring rocks, to scrape the meat from scavenged carcasses, over hundreds of thousands of years of peer group review and testing in the field, to the cheap serrated metal carving knife with which I sliced up the turkey at Christmas. The demonstrable truth of seven billion people on the planet tells us that science has thus far advanced our basic ability to survive rather than hindered it.

And so, as science increasingly becomes part of culture, as artists we are influenced by it and inspired by it. As a writer and lyric writer who occasionally reads Scientific American and a whole host of popular science books from the last twenty years, I have increasingly found that my creative work is inspired by the language of science —subconsciously at first, serendipitously proving for me that science is culture—making me a darwinpunk romantic poet, who can see what Dawkins calls “the magic of reality” in nature, but embracing the new enlightenment as a source of inspiration, rather than rejecting it.

Wilson goes as far to say that “there is a real creation story of humanity, and one only, and it is not a myth.” And by way of the scientific method “it is being worked out and tested and enriched and strengthened step by step.” As a writer I know because of science that there is an updated creation story, and I also know it is only good for now and will need more updating the more we discover in times to come. For now it could read be précised thus:

Nature only becomes more wonderful, for the knowledge that honey bee pollinates the flower that grows into the apple, and allows us to be humbled by the taste of the apple, rather than be doomed by the original sin of it. And, there is no sweeter joy than comingling with someone you love, under an apple tree in autumn, and observing an apple fall to the ground, in effect repeating Newton’s observation, and proving that we are bound to this earth by gravity.

At school in the 1970’s science, then split into the triumvirate of subjects of Chemistry, Physics and Biology, was mostly uninspiring. A rogue chemistry teacher did separate hydrogen from water to fill a balloon, which he then maneuvered with a yardstick over a Bunsen Burner, causing a movie-like zeppelin explosion of rolling clouds of flames and smoke. Our classroom at the time was a wood and fiber-board Portakabin, could easily have gone up too. It grabbed our attention and it could never happen today, but it wasn’t enough to reconnect me with my inner scientist.

As a twentysomething anarchist in the 1980’s my faith in science was not high. At the height of Reagan’s Cold War the doomsday clock seemed to marching ever closer to midnight, and I saw the commercial exploitation of science to make the most useless and wasteful plastic crap, or to test cigarettes on dogs, as a problem with science, rather than seeing science, like many other worthwhile human endeavors, as being held hostage to our economic system.

In two weeks time my twin children become teenagers and in them there is a real tale of science and creation. My faith in science was reborn at this most basic evolutionary level: the mixing of my genes with those of my partner in the adventure of a lifetime to create life. In order to bypass Fallopian tubes damaged by pelvic inflammatory disease we underwent in vitro fertilization (IVF) in England. Some twenty-plus years after Louise Brown, the first ‘test tube baby” was born, our doctor told us that IVF was developed to solve this very problem of blocked tubes, and because everything else in our case was looking good, it was ‘a simple plumbing operation.’

And so it proved to be, and our girl-boy twins were born at the first attempt. There will probably be nothing more humbling in my whole life than to have been completely involved in, but once removed from, the traditional primeval act of creating life, and then to have born witness to it in intimate microscopic detail, where the magic of science allowed us to see our babies grow from when they were but four cells big. In our children I am of course reminded of the wonders of science every single day and I can see too that they have some of their mom and dad’s artistic genes.

After our children were born, on English TV they were showing a series of documentaries on IVF marking Louise Brown’s twenty-fifth birthday. One of them was about how, around the time of her birth, the Christian anti-abortion Right in England had mounted very vocal and public demonstrations declaiming IVF as the Devil’s work, and absolutely counter to God’s will. I had had no idea that such a culture war had even occurred. As the film showed, when IVF became more widespread and more successful the campaign against it collapsed under the weight of its own misguidedness. The culture of science —theory, rigorous testing and peer group assessment, to repeatedly demonstrate verifiable truths— was evidenced in it helping to make babies for parents, some of them good Christians, where nature or God, could not. It was no contest.

For those of us not too damaged by surviving, fathers as well as mothers, in those spectacular first moments, as we hold our new born babies in their first minutes and hours of life, there is some communion that occurs which unlocks the hard-wired drives of both baby and parent to bond in a lifelong commitment. In having the nature awakened in us we instinctively nurture, and like our ancestors going back hundreds of generations in time, we begin a whole new series of trial and error experiments with the thing we call the human condition.

—Danbert Nobacon is currently writing a collection of just so evolution stories reflecting the birth and growing pains of the human condition, and an album of songs entitled Atoms to Atoms, Stardust to Darwindust

.

I suggest you read some real anthropology and steer clear of E.O. Wilson and his biological determinism called sociobiology which leads to the crap you have repeated, misrepresenting our current understanding of our primate ancestors, our hominid forebearers and the processes of evolution. I won’t go into detailed criticism here but this article also reflects a simplistic notion about science as well. Homo sapiens have survived not because we have been “problem solvers” (we also created bombs, spread diseases, pursued genocide, etc…) but because our adaptaion has been general enough for us to adapt to changes like the ice age which was probably not so for Neanderthals (whether or not they had ‘religion’). Read some more and people like Ian Tattersall and Alison Jolly, among others. Sorry to be so negative but this glib uninformed analysis was too much to keep silent about.

As an artist scientific discussion of the human condition is fascinating to me, so

why would I “steer clear of E.O. Wilson” who has interesting things to say about it. I think Tattersall (Masters of the Planet) is on the same page as Wilson in his assessment of the human condition describing us as individuals: “who are typically bundles of paradoxes, each of us mixing admirable with less worthy traits, even expressing the same trait differently at different times,” and that “we are ruled by reason, but only until our hormones take over.” The science of our origins, as I said, has been revolutionized in recent years. As we find out more, maybe in another twenty years, we will think quite differently again about our origins and ways of being.

I liked your article Danbert! And although I consider myself to be someone who has been recently released from “mind” prison, I can grasp what it is your saying and even if its not really what your trying to say it opens up my floodgates of thought:) Thanks!

I own a mind prison (created it, actually). Though it is occupied at the moment.

Just don’t send me a birthday party invitation next year and i’ll continue to donate bits and pieces of my thoughts.