IT WAS A chilly October day in 1996 when my mom called me from her Baltimore apartment. “He’s gone, Michael.” Her voice cracked like plaster. “I knew as soon as they started cutting off his limbs, he wouldn’t be around too long after.” The he was my mom’s father Len Mosby.

Granddaddy was a diabetic who, a few months before, had his right foot amputated. Days before his death, the doctors considered removing his entire leg. A handsome light-skinned man who was already middle-aged and bald when we I was four. Diabetes had wreaked him completely. Closing my eyes, I now imagined the once tall, broad shouldered man reduced to a small and shriveled shell lying lifeless in a hospital bed.

In Hagerstown, Maryland, the small town where he lived after moving from nearby West Virginia decades before, Granddad was a respected man. He was well read and owned a few properties and knew a lot about business deals. He could quote the Bible, admired W.E.B. DuBois and had read a book about the president of Wal-Mart years before most of the country even heard of Sam Walton.

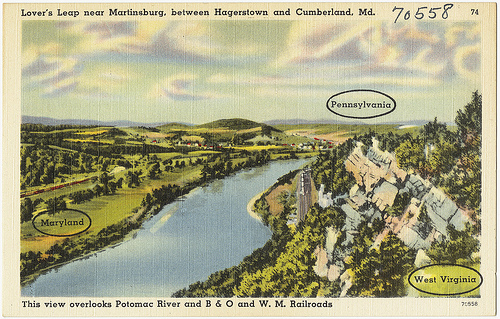

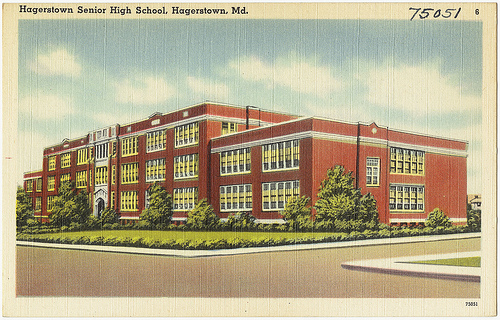

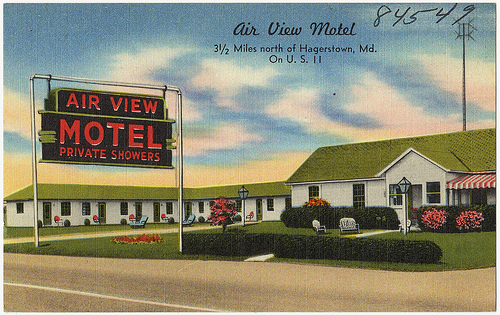

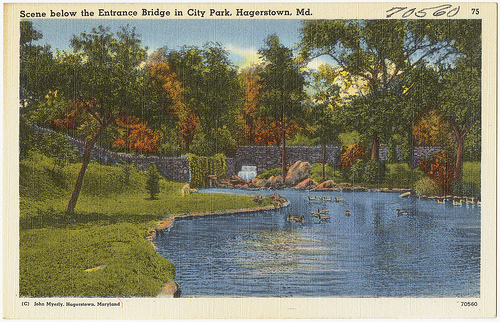

Lovers Leap, Hagerstown on the border… all images courtesy of the Boston Public Library via flickr

I can remember him sitting in his La-Z-Boy, eyeglasses perched on his forehead, flipping through Readers Digest. On Sunday afternoons after church, he would be watching football games or some old black-and-white movie.

Years before, Hagerstown resembled my own personal Norman Rockwell painting. A tiny town most folks drove through on their way further South, it was a quaint assemblage of neat houses, modest people, crowded churches and loving colored families whose small world revolved around family, school, work and God.

Back in the day, when Mom and I both lived in Harlem, I relished coming to that hick town that took us two buses to get too. There wasn’t a straight route from New York City, so we rode three hours from midtown Manhattan to the dingy Baltimore terminal, then waited hours for a connecting bus. Since the Greyhound station in Baltimore, with its shady game room full of ringing pinball machines, dirty floors and trespassing transients, made Mom nervous, we often went across the street to the Mayfair Theater until it was time to roll out.

Visiting was a welcome reprieve from the hustle of my native Harlem. At night, crickets replaced the wail of police sirens, and lightening bugs flickered in the front yard. Here was a magical place where my relatives lived down the road from one another and kindly Uncle Len ran the neighborhood grocery store.

My mother’s stepbrother, he was a tall man, soft spoken and stern as a preacher. Like his now dead father, my grandfather, he too was named Len Mosby, but everybody simply called him Len Junior.

Back in the day, when Mom and I rode into the town, tired after traveling hours from New York, I loved going to Uncle Len’s shop. He worked with his wife, Aunt Carrie, and they’d let me make cherry slushes for customers while he racked the cigarettes. On the counter a jar of pickled pig feet submerged in vinegar looked like something from a biology class, and a long strip of yellowish brown flypaper dangled from the ceiling. Dozens of flies were stuck to the surface, some with their wings still fluttering. Nonetheless, in his clean white apron Uncle James Len proudly watched over the store.

When my mom called about my grandfather, it had been years since I’d set foot in Hagerstown. I met her in Baltimore, and we rode in together. What had once seemed so exciting now looked drab and forlorn. The town I once knew had transformed like the boring, dusty burg in The Last Picture Show. Even the bus station was in a different spot. Hell, it wasn’t really a station anymore but merely an aluminum bench and matching shelter on the side of the road, as if even the bush station had been lost here.

Rolling our suitcases in the dirt, we walked to the first cab we saw. Years before, Granddaddy would’ve been waiting for us, smiling proudly in his station wagon, jumping out of the shiny car to hug his daughter. Instead, a taxi driver, a black man in his late thirties, put our suitcases in the trunk. Inside, the beat-up cab a tiny plastic fan on the dashboard blew hot air. I took a deep breath and tasted the town on my tongue as we turned onto Jonathan Street.

Outside, the candy store where I once bought Marvel Comics was now a XXX Porn emporium and the old movie theater a drive-through McDonalds. A few blocks later, Uncle Len’s store was boarded-up.

“Damn shame,” Mom said, “your Uncle Len had to lose his place.” She glared at the rusted lock that bolted the doors and the building’s crumbling façade. The once-bustling business was reduced to another Seventies memory stored in my mind along with platform shoes, Afro-pics, black velvet posters and scratched Jackson 5 records.

“If you ask me,” I said, “the entire town seems to be on a downward spiral.”

“Yeah, well that’s been happening here for years. When you were little, they opened the mall and just about killed what used to be the downtown business district. The old mom and pop stores were the first to go.”

“I don’t remember that.”

“Well, it didn’t happen all at once. Just a little bit at a time, but, over time it happened.” The middle-class sheen that once sparkled throughout the old neighborhood was tarnished by empty lots, boarded-up buildings and cracked-out zombies walking aimlessly or loitering in doorways.

Granddaddy was mom’s real father, although she hadn’t found out the truth until she was a teenager. Raised in Pittsburgh for the first sixteen years of her life, she’d grown-up believing that her step-father, a kindly man whom she often told stories about, was her father. Yet, soon after his death, my grandma schooled her in the truth, just one of the many skeletons dangling in our closet..

The taxi slowed in front of Aunt Evelyn’s medium-sized house. Grandaddy’s wife, she was my step-grandmother, I suppose, though no one ever used that term. With its freshly clipped lawn and flowers in full bloom, her home looked out of place . The nice homes that were once across the street had been replaced by a red brick housing project stretching from corner to corner.

Outside, small children played roughly in the dirt while a few feet away, older black boys, looking like some kind of outlaw posse, shared a forty-ounce of brew and shot dice. The ground was littered with cigarette butts, candy wrappers, discarded beer bottles, condom wrappers and whatever else might blow up the street or be thrown out of windows.

Mom handed the driver a ten-dollar bill and told him to keep the change. He thanked her in his best country drawl. Standing next to him as he lifted out our bags, I finally recognized him as an old friend of my cousin Chunky, Uncle Len’s son.

Six years older than me, Chunky was my hero when we were kids. He’d let me hangout with him and his buddies, riding around in the backseat of his powerful ‘73 Ford blasting the latest funk singles and smoking Kool cigarettes. He too was named Len, but became “Chunky” when he started playing football in the dirt lot behind his house.

A former fat kid when he first ran out on the field, Chunky found his passion in that first tackle. Within six months, his muscles were tighter than old Army boots and no other kid in town could run a touchdown like him. “One of my friends started calling me Chunky,” he’d told me when I’d asked about his nickname. “One day in gym class he looked at me and said, ‘Damn boy, you done gone from husky to Chunky.’ After that, the name just stuck.”

I asked the driver if the two of them had been friends.

“Me and Chunky used to be tight,” he said. “Played ball together, the whole nine. Man, might as well been a million years ago.”

“You ever go see him?”

The driver laughed. “Man, I got a family to feed and a cab to drive. Ain’t got no time to be visiting cats in prison.”

“It’s a damn shame what that boy put his parents through,” Mom said, her voice sharp. “Len and Carrie gave that boy everything and he repays them by becoming a criminal.”

“I’m sure it wasn’t on purpose.” I wanted to defend the memory of a man I hadn’t seen in over two decades. I didn’t know the particulars of Chunky’s downfall but knew it had to do with drugs. One minute he was in college with a football scholarship, the next in jail.

“Sure, Michael, it wasn’t his fault. You damn kids are always looking for excuses.”

“I didn’t mean it like that, ma. I just meant, that really wasn’t the Chunky I knew.”

Inside, the house was like a time capsule of vintage furniture covered in plastic slipcovers, a reproduction of Blue Boy on the wall, the polished black upright piano stacked with framed photographs and Southern soul food cooking drifting from the kitchen.

A former domestic, Aunt Evelyn’s house was spotless. “My goodness,” she said, “would you look at these two?” Her voice was sad, and she hugged me tightly.

“How you doing, Aunt Evelyn.” I whispered in her ear, not knowing what to say.

“As can be expected, baby. As can be expected.”

Across the room was Vonnie, Aunt Evelyn’s daughter, smiling. A preacher, she was “a woman of the cloth,” although her own son Ryan was another one of my cousins who couldn’t stay out of jail.

The living room, as well as the dining room and kitchen, was filled with various generations of women and a few older men. Even if we weren’t all blood, we were all related by the legacy Granddad left behind. On one of the dustless shelves, there was black and white photograph of him in his youth, dressed in a crisp army uniform and wearing a dour expression. A few feet away was another picture of him years later in front of the house wearing a white shirt and tie, black pants and suspenders.

He’d once told me when I was six or seven that I hung around my mother too much.

“Come outside with me,” he’d said when I’d been in the kitchen listening to the ladies talk. As we stood out on the front lawn, a skinny man with a massive Afro swayed down the street in glittery blue platforms wearing tight jeans and top. I was too young to know straight from gay, but years later realized he was probably the first out gay man in town.

“Hello, Mr. Mosby,” the man said, his voice delicate as my grandmother’s roses.

“Hey,” Granddad said, just one word like a growling bulldog. After the glittery platforms passed, Granddaddy leaned down. “You see him? He used to be up underneath his mother all the time too.”

Now I told my mother I’d take our bags upstairs. As I passed the dining room, I, I saw Uncle Len surrounded by male relatives I vaguely recognized. He sat erect in the chair in glasses and a button-down shirt, looking the same as he had behind the counter of his store.

Upstairs in the television room, I was shocked to see Vonnie’s son, my cousin Ryan, lounging in granddad’s old La-Z-Boy chair, flicking the channels on a boxy television. “What the hell?” I said, “I thought your ass was still in jail.”

Another spoiled kid when we was growing-up, Ryan had exchanged his private school education for a life of petty crime. Having become a charming conman and thief, he skipped getting a job, for robbing old white men on public golf courses.

He tossed aside the remote and smiled slyly. “I became born again, and the warden got my sentence shorted.”

“From crack to Christ, huh?”

“Just because you never been locked down don’t make you better than me.” He gave me a brotherly hug. “Long as you stay black, that shit can happen at anytime.”

“Tell me about it.”

“Plus,” he said, “I wasn’t smoking crack. I was smoking angel dust.” Looking at one another, we both laughed. “I started writing poetry when I was in jail. It was one of the things that helped me through that madness. You want to hear one?”

“Do I have too?” I sighed. “I hate poetry.”

“I thought you were a writer?”

“I am, but I’m a music critic. I don’t like poetry unless it’s a song. If you can sing the motherfucker with some music in the background, cool. Otherwise, I don’t want to hear it.”

“All right. Damn nigga, I thought you might want to encourage my writing.”

“Poetry isn’t something I would encourage.”

“That’s cool, bro. Respect. So, you wanna go outside and smoke a joint?”

I couldn’t help but laugh. “Naw, you crazy, man. We going to come back in this smelling like weed.” Although I was thirty-four, one year older than Christ when he was crucified, merely being in that house had reduced me back to short pants and Buster Brown shoes.

“Man, we’re grown. We can do and smell anyway we want.”

“You so bad, why don’t you go by yourself.”

“You know if I go by myself everybody going to know I’m doing something bad,” Ryan grinned and passed me the bag of potent pot. “Already got one rolled, thick as Bob Marley’s arm.”

“As long as there ain’t no dust in it,” I said. “Smoked that shit once and damn near lost my mind.”

“Would I do that to you, cuz?”

“Yeah, nigga, you would.”

Outside, thick black clouds hovered in the sky, looking as though they might explode at any moment. Walking up the block, we passed the public pool where as kids we used to swim. When I was ten, I had almost drowned there. From that moment, I realized that death could snatch you away at anytime. Though it was closed, the pool hadn’t been drained, and dead leaves now floated on top of the green murky water.

A cool breeze blew a black plastic bag through the beat-down playground. Where there was once grass had been worn down to patches of dirt. Where once the playground’s spinning wheel was a vibrant crimson, the red paint had peeled away, leaving nothing but rust. Leaning over, I picked-up a muddy rock and nervously rolled it around in my hand.

“I heard they were letting Chunky come home for Pop-pop’s funeral,” Ryan said, using his special name for granddaddy, which I always thought was the most country shit I’d ever heard. “He should be here in the morning.”

“What happened to Chunky?” I asked.

“What do you mean?”

“I mean, he had it all. He had a football scholarship, good parents, a fine-ass girlfriend and a hot car.”

“Man, you remember that car. Nigga used to be in there like that was his second home. Fixin’ it, drivin’ it, playin’ Grover Washington and Rufus’ ‘Tell Me Something Good.’ Man, I loved that car.”

“Not as much as Chunky did.”

Exhaling clouds of weed smoke for a brief moment, I imagined Chunky in chains, being dragged like King Kong by two pale faced prison deputies escorting him through the wooden church doors. Hard faced white men who’d rather be anywhere on the planet besides a Negro funeral on Sunday morning would be standing at either side of him like marble pillars.

“He’s not in prison anymore,” Ryan said, “they got him in a halfway house just outside of town. He should’ve been home, but he was busted with some cocaine inside. Judge made him go to rehab before coming home.”

“Man, you seen this fucking town,” I said. “Doesn’t really look like the kind of place that is scared of rehab.” Leaning back, I flung the rock as far as it would go. Somewhere in the distance, a police siren wailed. As though God was trying to tell us something, lightening cracked at the sky.

“What happened to this place?”

“Same thing that happened to all these little towns, man,” Ryan said. “Drugs happened, crack happened, poverty happened. Shit, what you getting so excited about? At least after tomorrow you get to go home, back to New York City. Some of us ain’t got that choice. Now, smoke some more weed and shut the hell up.”

Years ago, Granddaddy offered to buy my mother a house in Hagerstown, but she refused. “I couldn’t have you growing-up in that little town,” she explained years later. “There was nothing to do there. Why you think all your cousins wound-up in jail? Ain’t nothing to do.”

The clouds finally exploded, and Ryan and I ran back to the house drenched and smelling of rain. It was obvious from Mom’s glare that she smelled the weed wafting from Ryan and me, but she remained silent.

With all the relatives in town, there wasn’t enough room at Aunt Evelyn’s for us to spend the night, so Mom and I stayed with one of granddaddy’s Masonic brothers. His house was an old place at the end of the block that reminded me of a haunted house in a B-movie. The small place was sparsely furnished and poorly-lit. I wasn’t sure what the house was used for, since no one seemed to live there, yet our rooms were neat and clean. Still, it felt spooky.

After the rainstorm, the humidity had come back double, and I lay sweating on the bed. Feeling like a prisoner, I had trouble sleeping. I’d left the radio tuned to a local rock station, and every time I awoke, Eric Clapton’s melancholy “Tears in Heaven” was playing. I crept downstairs searching for a snack. The only thing in the vintage Frigidaire were a hundred cans of Diet Pepsi.

Back in my room, I sat on the bed sipping the cold soda and thinking about Chunky and Ryan, Uncle Len and Granddad, prison and death. Part of me wished I’d grown-up in Hagerstown and been closer to granddad as we both got older and our worlds began to change, as the innocence of the town disappeared, becoming something ugly that I no longer recognized. I ambled to the open window. Outside watching the darkened street, I silently waited for something to happen.

It’s funny, the image of the small town being all quaint when, if there’s nothing to do, there’s just idle hands.

Love the phrase ‘From crack to Christ.’ That would make a really great title for something, I reckon.

Pingback: 104 Weeks of The Weeklings: The Best of Our First Two Years | The Weeklings