THANK YOU ALL FOR COMING today to this memorial service for Philip Schneiderman.

My father was born on April 10, 1947, the last child of three—a Baby Boomer—in celebration of the new world emerging after the horrors of WWII. And he died, Phil Schneiderman, on Thursday, February 26, 2015, but not for the first time.

That’s right, Phil Schneiderman died twice, if we listen to his own difficult words. He died for the first time on Dec 5, 2005, in the following way:

Phil, 58, already the victim of creeping peripheral neuropathy that prefigured the slow death of the nerve endings in his feet, wakes for another day at the nearby office—a rented space from his company, Key Equipment Finance—where he will make calls to clients, plot trips to on-site locations for customer interactions, and prepare expense reports from previous trips, where business dinners would cause Phil to order a single screwdriver before secretly telling the waitress during a “bathroom” trip to keep them coming…with orange juice only.

Phil will spend hours on the phone, not only with his customers and coworkers, but also with any number of a large army of colleagues, many of whom are long-time admirers from the many different merger-happy companies he worked at over the years: Bank of America, Chrysler First, Key Equipment Finance, American Express, Deutsche Bank. In his role as advisor, he will strategize, consult; his advice builds upon the connections he’s amassed over the years, and he will help move people from one job to another, one city to another, one life to another.

He will imagine these possibilities, I know, during the two-mile drive down Manchester Road in suburban St. Louis, toward Clayton Ave. and its sprawling intercourse of strip malls and chain restaurants.

He will sing along to his Motown hits CD—perhaps to something tasteful like Smokey Robinson’s “More Love,” but just as likely to the Michael McDonald “Ain’t No Mountain High Enough.”

For Phil, the qualities of these are essentially the same, just as the taste of instant coffee he drinks at home is of the same kind that he would drink at a restaurant.

Phil lives in a world where most things have found their own level.

At lunch, he exits to grab a slice of pizza and then browses through the stacks at Barnes and Noble. Feeling a bit “off,” he drives the few back toward the office. He exits the car, and takes out his key, which glints, we might imagine, in the mid-afternoon light, a symbol of something to come.

And then, suddenly, he dies.

The key, frozen in the sun, is a signal flare between the land of the living—and of the real—that until that moment Phil has been a part of, and the shadowy realm he has now entered, the place of the aphasic, the swollen, the tumored.

After the door slams Phil feels an urge to return home—he knows something is wrong—and so he holds up his key to unlock the car door…and he takes out his key to unlock the car door…and he takes out his key to unlock the door.

And he turns the key, and turns the key.

And he turns the key.

The key is air. The key is made of air. The key is his finger. The lock is made of jelly.

Struggling across the parking lot and back toward the office, Phil crashes onto the couch in the foyer. No one notices, and no one passes him—lunch now long over and the other residents returned to the white-walled anonymity of their offices with pictures of eagles and mountains and inspirational quotations about teamwork and decision-making, and therefore about nothing.

The swelling of the tumor—glioblastoma multiforme—causes the brain to push against the skull, to rub away the layers of Phil’s complex personality, and to produce when he is finally discovered by a colleague exiting at 5 pm, the aphasic brain of a man whose memories are there, somewhere—along the edge of a distant planetary rim, interrupted by a meteor at the junction of the past and the future.

That day, the old Phil Schneiderman dies. And he never comes back.

Yet just as the shade takes its form from an object that blocks the light, the second Phil Schneiderman is already there in outline. The doctors open his skull and remove what they safely can of the tumor. They insert radiation wafers that degrade over months, and the new Phil emerges from that degradation: He engages in chemotherapy, takes 60+ pills a day, and submits to the poking, the prodding, the scanning of his body that will never cease for a moment until the time he dies again.

He travels to the Preston Robert Tisch Brain Tumor Center at Duke every few months, at first, where Dr. Friedman and Dr. Desjardins marvel at his ability to survive. What they don’t know is that this isn’t so much the old Phil Schneiderman surviving, as the new Phil Schneiderman—the second one—struggling to be born.

The midwife of this birth is his wife of so many years, Ruth, whose devotion and constant care keeps the new Phil alive. Ruth sacrifices everything so that the new Phil can have what he needs to keep going. She sublimates her ever-joyful spontaneity to the dirge of the repetitive: Phil wants to eat at the same two restaurants in the same order on the same days of the week—with leftovers consumed on the same off night.

She organizes her life around the scheduling and transport of what seems to be dozens of doctors and scores of medicines. She maintains, against her own need for peace. the constant bright lights of their bedroom and the blasting klaxon sounds of 24-hours news that provides, in its constancy and repetition, an anchor of sorts to the world that the first Phil once felt himself so strongly a part.

The new Phil, unable to find his pronouns, unable to name his relatives, unable to find the word “flashlight,” or “necktie”—because (at least metaphorically) these words have ceased to be of any use value—will class his memories to me in two ways. There are two epochs: 1) “Before I died” and 2) “After I died.”

This is an error, but it also a fact.

The first Phil Schneiderman’s family inherited a mirror whose partner was a narrow horizontal strip of decorative mirror. The young boy, called “Flip” by his father, would peer inside this strip, into a looking glass room that he would never reach.

His boyhood in Brooklyn, Long Island, and Brooklyn again, bore the markers of mid-century innocence—throwing peach pits around the room with his brother; roller skating instead of attending Hebrew School; working at Faber’s Fascination on Coney Island; apprenticing as a photographer’s assistant; and later, famously, selling typewriter ribbon with his brother-in-law Marty around Long Island, in a con straight out of Tom Sawyer.

Yet the first Phil Schneiderman reached maturity in an age of increasingly political complexity. His lackluster grades reached new levels academic seriousness at New England College, prodded equally by his not-unrelated interests in American history and of not dying in Vietnam.

By 1970, the newly married and graduate-school-enrolled Phil saw himself as a professor at a small liberal arts college, in the style of his own history teacher Ian Morrison. Events soon led him soon become a middle school- and then high school- history teacher in mid-state Delaware; just before the birth of my sister in 1978, gave it all up for a career completely antithetical to what he wanted to do. Because the salary for a teacher was not be enough to support his growing family, the first Phil Schneiderman became a salesman.

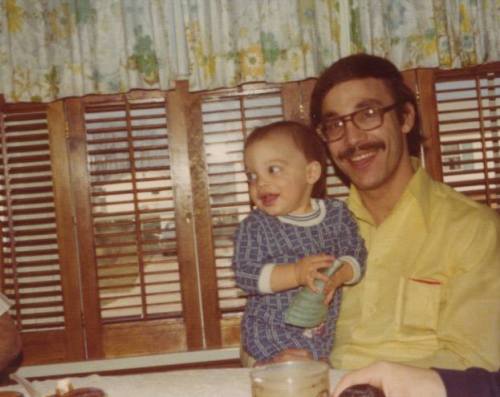

At Xerox, in Wilmington, Delaware—his first break—he would take the copy orders of corporate clients at their locations, have copies made at the Wilmington plant, and then hand-deliver the resulting mimeos to the businesses. He used the machines for other purposes as well, making dozens of copies with me, a boy of three, of a t-shirt proclaiming, “I’m the Big Brother.” Phil always had a plan. These sheets of rainbow ink prepared me for the arrival not only of Lisa—I see now—but also of his life as a traveling salesman.

In sales, Phil found his calling, or at least another calling beyond the minutiae of Civil War battles and Reconstruction politics. Phil had the loquaciousness of his father, Paul, a trait I have inherited and which I attribute without any evidence to an even earlier Philip Schneiderman, my father’s grandfather, Fischel.

I imagine Fischel’s journey to Ellis Island in 1913 peppered—on a cramped boat across the Atlantic—with stories of life in the Pale of Settlement between Russia and Poland, where our family talked themselves through generations in the Shtetl with all the success that would later back Phil Schneiderman, Vice President of Sales, in the strange 1980s America of Ronald Reagan and Lee Iacocca.

The first Phil was a talker.

And talking, you see, is the family business.

And so he closed his first big deal with Carrier Corporation in Syracuse, N.Y., in the mid 1980s—which cemented his place in the world of business that would take him, more or less happily, to that day in December 2005 where he held an invisible key in the air and turned and turned and turned and turned.

After his first death, I came to know the second Phil Schneiderman as if meeting a different father. His outline was familiar, but his shadow was strange. He could no longer care for himself, he could no longer provide for his family, and eventually, he could no longer manage his basic bodily needs.

And yet this second Phil Schneiderman was a person of great and amazing love. He understood, although he could no longer speak it, so many of things that had eluded him in his old life that was stuffed with so many endless words. In a new place where words are rare and hard-won, when interference from the tumor makes speech tangled upon its own collapsing logic, Phil better came to understand their value. Each day he spoke words to me that he had rarely said before: “I love you.”

That he could find those small words, still, in the space in his brain cut away by the surgeon’s knife, in the necrotic tissue flooding that hole the way dark matter pushes into a universe that we can neither measure nor understand, Phil made a discovery. In those small words that he could only access for me after his first death, the second Phil Schneiderman lived.

Yes, he came to know his grandchildren, he attended his daughter’s wedding, and he gained thousands of extra nights in which to squeeze my mother’s hand as they slept in uneasy quiet. But the way I will remember Phil’s life—his second life—is in those words that he found the capacity to say and to feel and to understand, because they came from a place of surrender.

He had to give up everything to find them: his career, his identity, and the control he desperately wanted to exert over everything. Phil had to discover in these last years of forced humility a meaning that we so often forget as we rush headlong into our next business deal, our next life success, our next throwaway purchase.

In the final days of his second life his world became so small that it might fit on the head of a pin. Even the noise of the 24-hour television was finally silenced to give him rest. In the end only his left eye could crack itself open to let us know that the second Phil was still there, somewhere, in a small way. And even then I could still hear what he was trying to tell me. I could hear his love emanating from the rapidly enclosing silence.

In the end, Phil knew how to speak without speaking. And I proud to say that he taught me how to listen.

For me, Phil Schneiderman’s brain cancer was not a battle. It was not a war he had to fight. He was not a soldier against the invading armies of disease.

Cancer is a fact. That is all it ever can be.

There once was a body, Phil’s old body, without cancer, and then there was the second Phil, born again into a body that had changed.

We certainly want to remember Phil as he was before he was sick. Let us never forget.

For many of us, that is the Phil we first knew and the Phil we first loved.

And yet I also ask that you today remember the second Phil with me—the one who lived these last nine years, and the one who finally stopped suffering last week.

Remember with me, friends, the second Phil Schneiderman.

Remember with me the second Phil Schneiderman, wracked with disease, enfeebled, aphasic.

Remember with me the second Phil Schneiderman, who told us each day—and in each blink of his finally closing eye—that he knew, when it mattered most, what it meant to love us each in return.

Note: an abbreviated version of this piece ran in HuffPo.