ALL MY ADULT life, I’d avoided writing screenplays. I didn’t know very many happy screenwriters. I didn’t know any, in fact: even the most successful among them, the ones who had sold pitches for six figures or seen their work solidly produced were miserable, touched with a kind of self-loathing unique to the breed. “A real writer,” says the magnificently-compensated television staff writer to the penniless novelist. “You’re a real writer.” Once, at a party, an Oscar-nominated writer/director—multiply-nominated, in various categories, for almost every film he’s ever made, winner of various other major awards likewise—turned to me and sighed. “To succeed in this business, one must make friends with despair.” It’s always been this way, and yet—

Yet, when I was offered a chance to write a script, I said yes. Of course I did. It was 1999, a period in which the narrowing window of “independent film” (scare quotes necessary to indicate I mean not truly independent cinema, but rather corporately-funded inexpensive movies) allowed the possibility of making literate adult dramas. Harvey and Bob Weinstein still ran Miramax, and the other studios—Sony, Paramount, even Warner Brothers as well as 20th Century Fox—had classics divisions. It seemed non-suicidal to attempt an adaptation of a difficult novel, an ambitious book that was, nevertheless at its core, a love story. I adored the novel, but my reasons for taking it on as a screenplay were fundamentally mercenary. As old, then, as the profession itself.

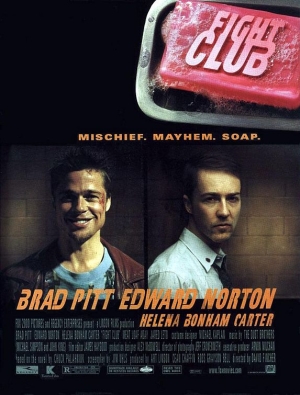

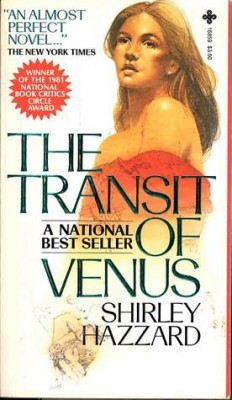

The book was Shirley Hazzard’s The Transit of Venus. I’d read it, first, when I was an executive. For indeed, I’d failed to escape the clutches of the industry altogether, no matter how hard I’d tried when I was younger. For most of the nineties, I was an executive based in New York, where I scoured the available pools for adaptable material. For a series of producers, and then finally for a studio, my job was to find properties—books, stageplays, articles—that could be translated successfully to the screen. It was a fascinating and yet weirdly difficult gig. Books passed through my hands, stalled at higher levels of decision-making, were optioned and then stalled again. What movies did get made through my agency were forgettable; the ones that didn’t, or the ones that got made despite my obliviousness (Fight Club landed on my desk, once, in manuscript: I told the sender I didn’t think anyone would make a movie like this in a million years), are too numerous to mention.

Still. I chanced upon Shirley Hazzard’s novel, which had been optioned—no, purchased outright—in 1982 by Polygram, a company that no longer existed. Neither the author nor her current agent had any idea who controlled the rights, or if they were retrievable. Because I like a challenge, or because I am an incorrigible masochist, I decided to try and unravel this puzzle myself. And as luck, or fate or chance, would have it, I was able to do so quickly enough, right around the same time a former assistant of mine went to work for a production company that had a development fund of its own. Might I be interested in writing the script, if they optioned it and paid me according to WGA standards? Thus it was that I became what I’d spent the better portion of a lifetime avoiding: I became a screenwriter. A screenwriter…

My incompetence, as I hashed out a first draft, was staggering. I’d decided, sensibly enough, that since the book had been in development before, and since any number of better-known screenwriters from David Williamson who’d written Gallipoli to David Hare and many others had already taken a crack at it, I’d be as freewheeling as possible. Throw two-thirds of the novel’s sprawling narrative away, condense, reconfigure: I’d leave the book on the shelf, once I’d read it a couple of times, and construct the script from memory and imagination. This seemed shrewd. I figured all the more conventional approaches would’ve been tried already, and there was nothing left but to try and treat this adaptation as an original. This, I imagined, would free me up. And so it did, to trip over my own feet and spin around in circles for . . . quite a while. I can remember plodding in from my office to tell my then-wife, “I’m writing the worst script ever devised by anyone,” perhaps a slight exaggeration given what I knew about scripts that had already been devised, but still. It turned out the form was monstrously difficult, and given my initial inability to get comfortable within it—to let dialogue do work that elsewhere had been done by descriptive prose; or to structure a three-act narrative in one hundred twenty pages—the self-loathing I’d witnessed in so many screenwriters growing up came home to roost. I felt like a fraud, and a fool. I couldn’t for the life of me figure out how to do what I’d been advising others upon for the better part of a decade: turn a prose narrative into a visual one.

The breakthrough came when my producer said to me, “Why don’t we remove _____?” He named a very specific aspect of the novel, one of the very few things I felt I hadn’t already gutted. Without it, the story would sink, I was sure of it. “You’re insane,” I said, displaying the same genius I had when I passed on Fight Club. “The whole narrative hinges on that.” “The whole book does,” he responded. “The book isn’t the movie.”

What did it mean for me to have this recognition, myself? All my life I’d been imagining the movie business and literature in strict—irreconcilable, in fact—opposition. At the same time, I’d tried to reconcile the two anyway. I was the world’s least likely studio executive, someone who went to the movies only rarely, and at the same time I’d discovered during my six-year stint as an executive, the business was crawling with people who did care about books, who, contrary to Hollywood lore, read them and had informed, articulate opinions about them, not just as cinematic properties but as literary performances. The business itself seemed to encode the same conflicts I’d always felt, the same things that had driven the exemplars of my childhood—not least my mother, whose own career as a screenwriter was a rueful one, marked always by the sense she should’ve been writing fiction—to such unhappiness. But then this was the business, too, or more specifically the writer’s role in it. A director makes films. An executive makes decisions. A writer, the person whose job it is to provide the blueprint for a movie, makes . . . nothing, most of the time, or at least is greeted with no tangible worldly evidence of what he has made. The script is either unproduced or, if the film in question actually does get made, so often altered beyond the writer’s liking or recognition. Seeing this, the cycle of despair starts to make sense.

Still. The moment this became clear to me in practice, as it related very specifically to something I was writing—The book is not the movie—the separation became easy, as clean as a yolk from an egg. I rewrote the script from the beginning, this time in four days. I delivered it to my producer on a Thursday, by Saturday morning we were receiving phone calls from studios, and within a week the project was set up, as they say. We had the art house division of a major studio behind us. So what next?

The script had initially faltered because I’d attempted to translate the book too literally, despite my best attempts to do otherwise. Once I’d stopped trying to replicate the novel—or even just the narrative—too exactly, people began to imagine the script was a faithful adaptation. Even ones who’d read the book repeatedly, whose attachment to the novel’s excellence was similar to my own, seemed to feel so. I hadn’t offended anyone, except potentially the author—to this day, Shirley has never read my script; in the interest of friendship, we’ve spared that moment of reckoning until or unless the movie actually gets made. But the script was met, in Hollywood, with enthusiasm. (I know, I know: yet the false enthusiasm for which this place is not-unjustly famous isn’t the kind I mean.) Actors and directors scrambled to attach themselves. One star flew to Paris to pitch herself to the director; another volunteered to undergo a boob job in order to reckon with the script’s one, relatively demure, nude scene (in which breast-size was neither important nor specified, but never mind). There was, in short, a sort of roiling frenzy, and yet an incomplete one. The difficulty was that we could never get enough people to say yes at the same time. The Oscar-winning star jumped to make a movie with Polanski; the director was then tempted away to make something else. By the time we replaced him, the Oscar-winner was available again, but the new director wanted somebody else for the part. An enormous American star, known for less-cerebral films, took an interest in the lead. Surely the producers and I could convince ourselves, given that his participation would mean an immediate green-light, the part was appropriate for him, that the monosyllabic action hero could plausibly play a British astrophysicist? Alas, no.

Round and round we went. I understood this—not just abstractly, but concretely, having been both a studio executive and a producer—to be part of the process, to be almost the entire process, barring the creation of an actual film itself. The making of a movie is a kind of coordinated accident; various persons think they control it, but the truth is, no one—not the star, nor the director, not the studio executive and certainly never the writer—in fact does. That no one does control it is, in truth, a large part of what people are chasing. It’s like surfing, in this respect. But of course, when one paddles out and misses a swell, one is left waiting for momentum, a gathering of energy that may, in fact, already have passed.

Such was the case here. We never could get all the pieces to function in harmony. Eventually, the studio head who’d brought in the project left and was replaced by another who euthanized it. My producers and I made various game—and then, increaingly half-hearted—efforts to resuscitate it elsewhere, to attach a new director, new stars. Eventually, though, we all moved on to other things. I still get calls on that script; now and then there are producers, or actors, or entities who’d like to revive it. They’re welcome to, assuming the turnaround costs aren’t prohibitive (which they’re not).

Still, though. What I found in writing the script, and in my subsequent adventures in the business (I’ve written several scripts since, none of which have been produced just yet) wasn’t despair, or desperation or self-loathing, and it still isn’t. Rigor, and difficulty perhaps, but I can’t imagine a meaningful occupation in this world from which those qualities are absent. I’ve written a couple novels in that span too, and those seem roughly parallel—as different as the process is, as radically private as fiction writing is compared to the collaborative clamor of screenwriting—in their experiential nature as well. Anything will give you an opportunity for self-loathing if you let it. Anything at all.

Which is why I look back at that experience, and that moment where my producer showed me what to cut—something I would never have considered otherwise, ever—with such gratitude. The book is not the movie. Surely. And the writer is not his or her work, nor the film industry itself. Whatever hope exists for any of us lies in just such separation, in our ability to parse our private selves from our products, and even from our feelings, the ones we generate in others and they generate in us. That may indeed be a working definition of “making friends with despair,” but it may instead be something else: a means of being authentic in—or out of—a business fabled for being the opposite; a way, whether one is a writer or not, to be real.

I truly love your blog.. Very nice colors & theme. Did you create this web site

yourself? Please reply back as I’m looking to create

my very own website and would love to know

where you got this from or what the theme is named.

Kudos!

Pingback: 104 Weeks of The Weeklings: The Best of Our First Two Years | The Weeklings