ALL THROUGH HIS twenties, I congratulated my son for not making me a grandma. Like I thought that was birth control. When he hit thirty, I shut up because I was afraid I’d never become a grandma. I guess I threw away The Pill. He had a son at 32.

Sitting across from me in his favorite San Francisco restaurant, my agent – white and erudite – thumped my novel manuscript, and said, “How come the humor in your conversation isn’t here on the page?” I was writing about the harrowing experiences of becoming a Black Panther in the sixties in San Francisco. Not exactly a fount of funny, I thought.

His favorite dish, the one he urged me to order, shrimp scampi with linguini, suddenly tasted papery. People routinely laughed at my takes on politics, sex, menopause and post menopause, being black, getting old while being black. My sense of humor is a survival skill. Surely I could put funny in the novel.

I was determined to figure this out how to get the humor that spilled from my mouth into my novel. I’ve always loved comedians. I saw Richard Pryor when he was a young comic at The Purple Onion in the city. My secret fantasy had long been to perform as a comic. If that would put my manuscript over the top I’d try it.

When my son’s girlfriend had her baby shower, I found out I wasn’t a grandma. I was the babydaddymomma.

Even so, I was proud. Then I went to buy a stroller and got sticker shock. It cost more than I paid for my first car.

I come from a long line of gabbers, but the performers I knew best were the preachers of my childhood—bombastic in their regal robes, kings of the church who had women, banquets, love offerings, parsonages provided without question. One famous local evangelist was rumored to have bitten off the nipple of a loving underage supplicant. Another beat his wife so severely the domestic abuse charges made the local papers. And, of course, I am from Oakland, the home of His Grace King Narcisse, he of the red-velvet ministry and Rolls-Royce flamboyance. As a daughter of a longtime church secretary, I heard it all- firsthand, secondhand, through rumors, gossip and innuendo. As an adolescent, I found it comical as well as disgraceful. Witnessing hypocrisy cultivated a sharp cynicism.

I saw Billy Graham on TV. He looked like Frankenstein. Face bloated , clothes too big. I had to Google him to make sure he was still alive.

Where were his handlers? I wanted to shout at them: Look up! Look at the monitor! Stop counting the money! Fix him!!

When I later joined the civil rights movement – the radical end through the black student movement and Black Panthers, again I saw the inner workings of a large social phenomenon and the contradictions between conviction and faith, privilege and sexism. My novel, Virgin Soul, explores the gradual radicalization of a young black woman in the midst of these contradictions. Humor was not my objective although my girlfriends and I – barely out of our teens – laughed our way through the violence, threats to our lives from police, the FBI, the agent provocateurs, and our own carelessness. It would take decades for me to understand that our silliness, giggles, and elbow poking at the outrageousness we witnessed protected us.

I still had to figure out where the funny would come from – or, at least, how to tread that line between the comic and painful. Using the local free papers, I found the underground comedy scene and made my way to the Brainwash Café. There I met a Bay Area legend, host/comic Tony Sparks. I went to his drop-a-buck-in-the-cup venues. The Tuesday one started around 7 pm. I was so unsure of myself that I’d wait until the room cleared and get up around 9:30 in front of the diehards.

It took me six weeks of going to the comedy venues to get a laugh. When I asked Tony’s advice, he commented that people listened to me intently because I was aging. Distressed, I repeated that and he shook his head: “I said it’s because you’re engaging.” He then suggested that I keep using narratives but inject punch lines every few sentences. I took the advice and started getting consistent laughs.

Ants drive me nuts! They’re so systematic…like armies. I think they have dictators, just like people, who send the little brown ants, the babies first—kind of like the Palestinians, young women and children first.

The world of comedy intrigued me. I never did a pratfall on stage, but, in the Tenderloin, passing by a bunch of drug dealers and dope heads, I trip and my straw bag spills out wallet, prescription drugs, loose change, and notebooks. I skin my knee, so scared I don’t know what to do. Everyone eagerly helps me. When I get to the comedy venue, I check and my stuff’s all there.

The babydaddy, my son, and the babymomma told me they had decided not to use the n-word around my grandson. The next time I had him, he said dammit every time he got frustrated. When they picked him up, I said, “Which one of you African-Americans uses dammit in front of him?”

I see progress. I go to a one-woman show by a comic friend of Tony’s. I enter the 3rd floor of a building in the Castro. It’s pitch dark; I fall over drums and a tympani that make a loud sound. I expect the noise to alert someone to help me. No one comes. I sit there in the dark until I pull it together. When I go in, I see why no one came out. There are only two people in the audience. Even though the solitary actor is dreadfully unfunny, I laugh to support her. Funny takes a lot of nerve, I’m finding out.

Black people have a disease called “I don’t wanna work for the man” and another disease—namebranditis. When these two diseases come together, it’s called “Broke.”

I don’t understood why the comics do the same routine over and over for weeks until I learn they’re working on the timing. Later, I see two of them on Last Comic Standing, doing the exact same routines to great laughs. I recall seeing Richard Pryor in his final public performance at The Circle Star Theater in San Carlos, dozing off onstage and working the hell out of a 20 minute set, his wheelchair and onstage nurse as much prop as medical necessity.

I was married for 11 years. So I identify with prisoners.

Who made marriage a gruesome marathon-”till death do us part”?

When I bring a big white vibrator with a purple head to the Brainwash, I get more laughs than ever and provide everyone who follows me with material. I see why prop comics go straight to Vegas.

I decide to bring my funny to a notoriously hard venue in Oakland. Luenell, who will grab her 15-minutes in Borat, hosts. One night, drunk, she moons the crowd, pulling her pants down and showing her big yellow backside to one and all. I don’t go on that night. I come another week and do a short set that bombs. In the middle of it, Luenell shouts, “You’re going over the head of these first-of-the-month n—–s.”

Another night, I do a successful bit on a black TV evangelist but make the mistake of inviting a favorite cousin who is a pastor. It gets laughs but not from her.

I finally get a paying gig when Tony invites me to a venue in Emeryville, a town next door to Oakland. I’m scared but bring a set list of bits that I keep going over during the evening. The feisty woman headliner takes one look at me and says, “Oh hell no!” Tony lets me know I’m out and apologizes, but says I can sit at the comics’ table and get free drinks. She ignores me but starts a rant. “I hate people who come out once a week and have the nerve to call themselves comedians.” She’s out five nights a week, she says, sometimes hitting two or three spots a night. I’m coming out maybe once a month at that point. She works the craft of comedy the way I work the craft of writing.

My son, like the comedienne, can’t believe I’m doing this. “Mom, you’re not a comic. You’re funny. Sometimes.” They’re both right. In trying to put the funny in my work, I discover my humor and sarcasm spring from the eruptions of irony in my daily life. I’m not a comic; I’m an ironist, an observational ironist. I venture closer to my novel’s subject matter, being a young black militant in the 60s.

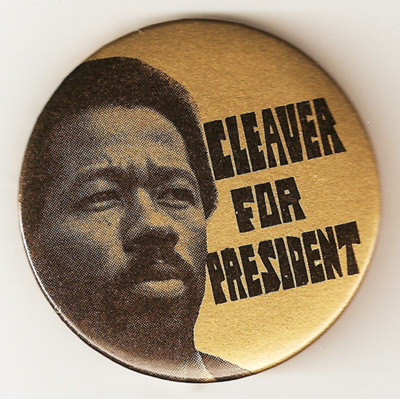

I was in the Black Panther Party as a teenager. For heaven’s sake, they welcomed white people. Out of all the militant groups, they welcomed white people with open arms. Armed with .357 magnums.

I realize that I’m not going to inject funny into my novel, any more than I can make shrimp scampi my favorite dish; my romance with comedy ends and I return to editing the manuscript. The writing becomes tighter and, in some way, laced with a deeper irony. Here’s an excerpt:

The next night, April 6th, Li-an gets a call. There’s been a shoot out in West Oakland between the police and the Party. We call and wait for another call, listen to the radio for news, pace the hall and wonder how bad it was. The radio responds with bits and pieces: Eldridge’s shot, several Panthers arrested, no police injured.

Finally, someone from the office calls the house: “The pigs killed Lil’ Bobby in cold blood. Eldridge got shot.” Li’l Bobby, the youngest of all, shot and killed. Seventeen years old, the first person to join the Party. I can’t fathom it. I can’t match his baby face with a body being plied with bullets in the heat of a fierce gun battle. In the space of the next 72 hours, I hear fifty-leven accounts of what happened. From Po-Rob, a brother from State who says he was in a caravan of cars out to get the pigs…led by Eldridge who stopped to pee…at which point pigs surrounded them and they vamped. From the Trib…which relies on pig-facts…Eldridge and Warren Wells were injured and held, with six brothers, on felony charges including carrying a concealed weapon and attempted murder. From the Party that says the police ambushed them. From Po-Rob who said the brothers ran and hid in different homes…some got caught…others got away. From brothers who say that Eldridge got naked before surrendering…to show that he was completely unarmed…but Li’l Bobby wouldn’t strip. From the Trib that says Li’l Bobby had a coat on and ran towards the police…crouching…and they couldn’t see his hands…shot him seven times. From the brothers who say they saw a volley of bullets electrifying Li’l Bobby. The Trib says, the brothers say, The Trib says, the brothers say…the more I hear, the more my insides go bananas. For days. I can’t stop crying screaming fainting listening recoiling retching agonizing, which no one hears or sees because it’s all inside me. Like drunks at an after-hours club, the details are stumbling all over creation, except for one: Li’l Bobby died.

this is soo wonderful….wanted to stop so i could get back to work,,,but had to finish…:)