In England, the goalkeeper is treated as a necessary evil. It’s a thankless position. One mistake and you’ve gone from being a hero to being a bum. – Esther Howard[1]

THOSE WORDS RING true. No kid ever wants to go in goal. No kid ever dreams of making a save in the World Cup final. To be put in goal is to be punished. The position of goalkeeper is reserved for the fat, the lazy, and the talentless. Nobody wants a goalkeeper, they just want a body between the posts. What does that say about the mentality of those children who choose to take that position? And what does it say about Esther Howard, who encouraged her son Tim, to take up the least popular position in the least popular sport in America?

At school in New Brunswick, NJ Tim Howard wasn’t like the other kids. In the Sixth Grade Howard was diagnosed with Tourette’s Syndrome. Contrary to the popular image of Tourette’s as “the swearing disease,” sufferers are more likely to experience facial jerks, spasms, and involuntary tics. Goalkeepers are always different. They tend to be natural outsiders. On the pitch this difference is further highlighted by the wearing of a different jersey – usually a jersey in garish neon colors. Kids aren’t different because they play in goal, they play in goal because they are different.

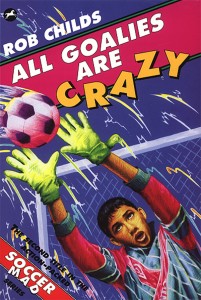

When I was at school I read a series of football-themed books by Rob Childs. The only story I recall was All Goalies Are Crazy. The plot follows the goalkeeping obsessed, and mildly eccentric, Sanjay, who finds himself dropped after a string of errors, and his attempts to win back his place in the team. I know that I read the entire series, but the fact that that is the only title I remember is probably a lot to do with the fact that I identified with Sanjay, as I was the only kid at school who wanted to play in goal. I was also different from most of my classmates – quieter, shier, but prone to telling outlandish lies. I once spent several weeks trying to convince my friend Saad that I was literally from a different planet. It almost worked.

All goalies are crazy – or else would make good writers.

Of course, I would likely have ended up in goal anyway, as one of the physically weakest, least talented players at school. As a timid child I had the requisite absence of ego required to play in a position that affords you almost no glory whatsoever. You also need thick skin to absorb the blame you will receive for each and every goal conceded (although at amateur level, ambivalence is an acceptable substitute). There are very few, if any, good reasons to be a goalkeeper. Even those who play in the position find it hard to explain why we do it. Tim Howard does not enjoy it at all, as he explained to The New Yorker a few years ago, “To tell you the truth, I don’t enjoy the game – I’ve never actually had fun within the course of those ninety minutes… When the whistle blows, I’m completely exhausted, physically and mentally. I get in the locker room and I sit down and I just exhale. Finally, the danger is over.”

Tim Howard eyes the ball for Everton…

Between the end of junior school and my final year of university, I hardly ever played. It was only then that I was called upon to replace my friend Liam as goalkeeper of the Itchen Minnows – a six-a-side team formed by my fellow students in Creative Writing and named after an incredibly small fish. It was not an inappropriate moniker. Interestingly the twelve weeks of that football season coincided with my most productive and prolific period as a writer. In four months I completed eight university assignments, published two essays, wrote one film script, a novel, and conceded just under fifty goals. And it would seem that there is, in fact, a link between these two factors – between being a writer, and being a goalkeeper.

Football has often been the subject of literature, with Nick Hornby’s excellent Fever Pitch perhaps the best known. Then, of course, there’s Rob Childs’ All Goalies are Crazy, and in literary fiction Austrian novelist Peter Handke’s even darker take on goalkeepers’ mental instability The Goalie’s Anxiety at the Penalty Kick, a novel which takes the outsider status of the goalkeeper to existential extremes as, after being sent off and conceding a penalty, he commits a murder in the same mindless vain of Albert Camus’s Meursault in L’Etranger. Also turned into a movie by Wim Wenders, Handke’s seemingly straightforward title, in this instance, refers to the psychological nightmare of the penalty as a metaphor for his goalkeeper’s ambiguous position as an as-yet unsuspected murderer.

http://youtu.be/dmpi9rfKzvw

Occasionally, football players themselves take to writing. Recently England midfielder Frank Lampard launched his own series of football-themed children’s books and nearly every ex-pro has an autobiography. These vary in quality, and are usually ghostwritten. The only example worth recommending is I Am Zlatan, from Sweden’s eccentric striker Zlatan Ibrahimovic.

However, there are only a handful of well-known writers who’ve played competitive football. And every one of them played as a goalkeeper.

The best known footballing goalkeeper is arguably Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, who not only created the most famous fictional character of all time but also started in goal for Portsmouth F.C. Very little is known about Conan Doyle’s career. He played under the pseudonym A.C. Smith, and the club disbanded in 1896.

It is very difficult – particularly with such scant information – to make any connection between Doyle’s writing career and his football career. In fact ACD was something of an all-round sportsman, a keen golfer and a talented cricketer who played First-class cricket, the sport’s highest professional level, for Marylebone Cricket Club.

Albert Camus, author of the aforementioned L’Etranger, is another author whose appreciation of, and involvement in football is well known and well documented. A French-Algerian, like the legendary Zinedine Zidane, Camus was a two-time winner of the North African Cup, and the North African Champions cup with his side RUA (Racing Universitaire d’Algers). There are also unconfirmed reports that he represented the Algerian national side in the 1930s. Sadly for Camus, his career ended at the age of just seventeen, when he contracted tuberculosis. Interviewed by the alumni sports magazine of the RUA where he’d been a student, he says about soccer: “After many years during which I saw many things, what I know most surely about morality and the duty of man I owe to sport and learned it in the RUA.” It is worth noting that amongst the many things Camus had seen, active participation in the French Resistance was one of them.

Aside from Vladimir Nabokov’s keen interests in butterfly collecting and chess, there was also at one time soccer. As a young man the future Lolita author studied at the Tenishev School in St. Petersburg, and played as goalkeeper for the university team. He described goalkeepers as ”the lone eagle, the man of mystery, the last defender.” He later went on to play for Trinity College, Cambridge described in his memoir Speak, Memory:

Mercifully the game would swing to the opposite end of the sodden field. A weak, weary drizzle would start, hesitate, and go on again…The far, blurred sounds, a cry, a whistle, the thud of a kick, all that was perfectly unimportant and had no connection with me. I was less the keeper of a soccer goal than the keeper of a secret. As with folded arms I lent my back against the left goalpost, I enjoyed the luxury of closing my eyes, and thus I would listen to my heart knocking and feel the blind drizzle on my face and hear, in the distance, the broken sounds of the game, and think of myself as of a fabulous exotic being in an English footballer’s disguise, composing verse in a tongue nobody understood about a remote country nobody knew. Small wonder I was not very popular with my team-mates.

Nabokov seems to view himself as simultaneously part of the team, but separate from it. Goalkeepers are rarely the hero, yet ‘Nabbsy’ seems to be picturing himself as some sort of mythic, mysterious lone cowboy type. I also find it hard to believe that he would be in a position to lean against either goalpost, or have the time to compose verse although he does seem to imply that he may not have been the most reliable goalkeeper.

Nabokov’s thoughts on goalkeeping also go against one of my own theories about why the position is so appealing to writers, which is to do with the almost Zen-like concentration required. The mind of a creative type is usually busy with ideas in a way which isn’t always helpful and hard to switch off. In my own experience, I found that once the gloves are on you are completely focused on the game, and the subconscious is finally quiet. It’s a kind of meditation, and an obvious benefit for a writer for whom constantly obsessing over their work is unhealthy and unconstructive.

In his 2010 New Yorker profile Tim Howard revealed that he refuses to take medication for his Tourette’s, for fear of losing his mental clarity and becoming “zombielike.” He also revealed that the intensity of his concentration moderates his symptoms and often temporarily rids himself of them entirely.

Perhaps there is something to Nabokov’s poetic philosophy towards goalkeeping. It is a very individual position – the loneliest, most isolated role on the pitch. It is not unprecedented for goalkeepers to endure long periods of inaction during a game. In the semi-final against Brazil, Germany’s Manuel Neuer rarely got a look at the ball. It is the only position in which much of the game is spent as an observer, rather than a participant. The psychological toil comes in not knowing when you will be called to participate and so must spend the entirety of the game in constant readiness. A goalkeeper must have a good imagination to picture the unexpected occurring at any given moment.

Linked to imagination is superstition. Goalkeepers tend to be the most superstitious players. At the 1998 World Cup the French ‘keeper Fabien Barthez insisted that his teammate Laurent Blanc kiss him on the head for good luck. Spain and Real Madrid No.1 Ilker Casillas would wear his socks inside out for each game, as well as touching the crossbar before kick-off (the latter being a practice shared by many other goalkeepers, including myself). Ireland goalkeeper Shay Given keeps a bottle of Holy Water in his goal, whilst Pepe Reina begins his superstitions six hours before kick-off, with a visit to the petrol station. The strangest goalkeeper superstition goes to Argentina’s Sergio Goyochea, who urinated on the pitch before facing a penalty.

Of course, the tortured psychology of goalkeeping probably offers the greatest reason for the link between goalkeeping and writers. Writing is an intensely psychological and philosophical pursuit, requiring heightened senses, understanding, and imagination. It also requires a paradoxical combination of vulnerability and mental resilience. Like the goalkeeper, the writer’s efforts rarely win plaudits, are barely even noticed and can all too often be for naught. To Tim Howard, his record-breaking performance meant nothing; his team still lost the game. His post-match comments echoed those he made in the New Yorker : “They’re trying to get the ball past you; you’re trying to stop it. Anything else is meaningless.”

Both roles share the psychological resilience required to get back up after every setback, and keep on going as though nothing has happened. Confidence is everything, and losing it can cost your place in the team, or even your career. In 2006 England’s Paul Robinson failed to clear a back pass that bobbled over his foot and went in. It effectively ended his international career, and it took several seasons for his club career to recover.

The goalie is also the most interesting position from a human point of view. It is also, arguably, where the most action, drama and comedy is found. Every goal features a beaten ‘keeper, whether the ball goes in as a result of genius, or a gentle tap in. Whether it’s a late winner, or a tragicomic deflection off a teammate into his own goal. The goalkeeper is always there, in the middle of it all – the heights of joy and the depths of despair.

To the writer, the penalty box is the most exciting part of the pitch. It is a sensory overload, an eighteen-yard box brimming with tension, frayed nerves, high hopes, and fallen dreams. It is a microcosm of the human experience. Where else are we really going to be?

I’d like to see what Netherlands’ Tim Krul would write.

Also, why all the “Tim” keepers? Is it because they know much that is hidden?

‘Tim’ is a tall persons name, I think. I’ve never known a Tim under 6′.

Krul is a fantastic keeper. Bit of a shame he’ll be remembered for his mind games in the shootout (which the ref should not have allowed).

I can introduce you to a Tim that’s under 6′. As a matter of fact, he’s so Tim-y his dad named him Tim twice. And he’s shorter than me. Which isn’t saying much.

I played goalie briefly myself, one autumn sometime around age 11 for a team called the Warriors. I didn’t last long after routinely freezing up when the offense came surging toward me. But like most American kids, I was only there for the halftime orange slices served by the soccer moms.

Tim Howard’s quote about never actually enjoying the game play sums it up I think. Maybe Howard releases a novella with an indie press sometime before the next World Cup, and maybe we all keep getting up after the setbacks.

I became surprisingly obsessed this year with the World Cup and am at a total loss now. David Luiz and Silva won’t cry when they lose with Paris St. Germain, so I find myself less interested. Looks like I better start writing again.

It’s terrifying when that happens. I always came charging out like Neuer does. Often the best thing to do is to rush out and attempt a slide tackle…

This was the sort of World Cup that converts people. It was the best tournament since France ’98, which is what turned me into a football fan. Brazil 2014 was (and was voted by a BBC poll) as the best tournament ever. It really did exhibit everything that is great (and in the case of Suarez, not so great) about the game.

Club football is better in the lower divisions. There’s no money, scant chance for glory, and everyone involved is just there for the love of the game.