An immense round water tower of a man named Sally trained me for the job. Sally was a black man, but he had the sweet lilting voice of a white Southern lady. He always sounded like he was just about to offer me a mint julep, which was disconcerting. And his name was Sally.

Sally had sleep apnea, a sleeping disorder that makes you stop breathing during the night, and you snore/snort yourself back into wakefulness every few minutes. It makes it nearly impossible to attain REM sleep, which is vital for both health and psychological stability.

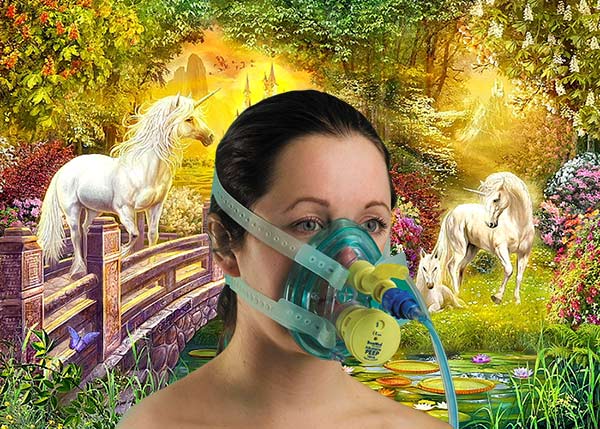

Sally had to sit up in a chair to sleep, and wear a device that forced air into his nostrils: a CPAP face-mask. CPAP is an acronym for “continuous positive airway pressure.” The device resembles the masks worn by the pilots of F-15 fighter jets—a clear plastic face-mask with a tube that runs to an oxygen tank. An alternative to respiratory intubation in patients with pulmonary disorders, it is also diagnosed for patients with sleep apnea.

Everyone that works night shift for more than a couple of years is overweight and suffers from sleep apnea. It comes from eating microwaved HotpocketsTM all the time and modern-jazzing your circadian rhythm.

If the circadian rhythm is the familiar, comfortable 4/4 of a sentimental pop tune, then the night shift worker’s rhythm is an experimental time signature that only functions as an intellectual abstract. 5/8 with random beats added, John Cage shit.

If the circadian rhythm is the familiar, comfortable 4/4 of a sentimental pop tune, then the night shift worker’s rhythm is an experimental time signature that only functions as an intellectual abstract. 5/8 with random beats added, John Cage shit.

Sadly, I failed to recognize Sally’s condition as the dire warning that it was. I thought he was a freak. What had happened to him could never happen to me, and even if it did, a hypothetical future of eating microwaved HotpocketsTM and sitting up to sleep while wearing a plastic face-mask that forced air into my nostrils seemed a fair exchange for never having to do anything ever again.

But I digress. I’m very sleepy, and I sometimes forget what I’m talking about.

I’ll start again.

Ten years ago I started working the night shift at a hotel, in a position known in the industry as night auditor, the primary duty of which is to remain conscious.

I was desperately lazy. The idea of doing anything at all—not to mention being compelled out of doors, forced to take part in the bustling activities of the world—filled me with loathing. I have never understood the achievers, the power-drivers, the three-piece-suiters with two coronaries under their belts, apoplectic, shouting into phones at subordinates, “Get it done yesterday!”

I prefer staying home, in my underpants, watching television shows about murder.

I often played sick as a child. Faking fever by holding the thermometer to the lamp while my mother was out of the room, popping it back into my mouth just before she returned. Whimpering as she ran her hand across my sweaty, liberal-application-of-heating-pad brow. Watching as the car backed down the drive, waiting out five . . . ten . . . fifteen minutes, until I was sure she wouldn’t come back, and then bounding down the stairs, fixing seventeen slices of cinnamon toast, watching cartoons all day. Making my voice sound feeble and scratchy when she phoned later on to see how I was doing. I was doing better, but not much better. I might have to stay out another day just to be on the safe side.

For the habitual malingerer, the only job more appealing than night auditor is test subject for sleep research, where—electrodes epoxied to your scalp, EEG pens crossing paper spools like the skittering legs of electric cockroaches, scrawling mountains and valleys indicating nightmares, bugbears, wet dreams–sleeping is the job.

But working the night shift slowly kills you. Research indicates that prolonged disruption of your circadian rhythm triggers a host of ailments, including cardiopulmonary disease, diabetes, stroke.

It takes a long time though. The progression is so gradual you wouldn’t even notice it. You enter the tunnel a lazy young man with a bright future of naps; you come out the other side with fourteen chins and sleep apnea.

CONSIDER THE BLIND MOLE RAT

Blind mole rats diverged from guinea pigs about 41 million years ago. They primarily inhabit a broad swath of soil around the Mediterranean extending from Southern Europe to the Middle East. Despite its name, the blind mole rat is not completely blind. A layer of skin and fur covers its vestigial eyes, atrophied from millennia dwelling in underground burrows. The blind mole rat has been the subject of numerous sleep research experiments because it is able to maintain its circadian rhythm despite the fact that it has no awareness of sunrise or sunset.

At first, the only negative to the night shift is the inconvenience of living at odds with the rest of the world. Everybody treats you like you’re lazy if you sleep through the day. There’s no compassion. And the city ordinances are stacked against you. Road crews can legally jackhammer pits into the sidewalk anytime past seven a.m. Groundskeepers can decimate hedges right outside your bedroom window with the buzzing serrated blades of gas-powered trimmers. Neighbors can stump their way through aerobics routines or hammer together shelving units. There’s nothing you can do about it. From 7 a.m. to 11 p.m., everybody has the right to stand in the yard and yodel, shatter aquariums with sledgehammers—anything.

Yes, there are earplugs, blindfolds, noise machines.

I usually tie a bandana over my eyes and crank up the ocean waves. I put a hoodie on and draw it so tightly around my face that there is only a nose-hole. I resemble a blind mole rat.

I seldom sleep a full eight hours. My schedule is broken up into fitful naps on the sofa. I drink myself into unconsciousness only to wake up three hours after the buzz has worn off. I count sheep. I drink even more. I vaporize weed. I guzzle lethal quantities of NyQuil. Sometimes I sleep for entire days.

After a few years of this, you begin to experience the deterioration of rational function. Like a high school kid with ADHD, staring out a window, I find myself incapable of concentrating or making decisions. And I’ve started snoring. I have become one of those sad middle-aged men banished to the ancient plaid pullout in the den, rusty springs under paper-thin mattress creaking at every toss and turn. I have begun to experience the phenomenon known as microsleep, where you fall asleep for seconds or minutes at a time, sitting, standing, walking. Whenever I open my eyes, I am somewhere else, pink light and black shadows flashing through my eyelids. The car is warm and comfortable. I don’t know where we’re going. Fortunately, I’m not driving. Odd phrases wend their way through my consciousness: Gehenna is a place of shades and weeping.

Efforts to regulate my sleep patterns have become an obsession.

I work only three nights a week now—Sunday, Monday, and Tuesday—from eleven at night to seven in the morning. I used to work the full forty hours, but this is no longer possible. As soon as I clock in, I immediately begin the paperwork, because I usually hit the time where I can no longer think sometime around three a.m. So I run reports, I check credit card tallies, I correct errors. I print registration cards for the next day’s guests. I program key-cards. I prepare breakfast cards and comment cards. I count the cash drawer. I settle the books. It takes about an hour and a half, and then I fuck off until around two a.m. when I have to lock the street doors.

I then devote two hours to the science fiction novel I’m writing that’s supposed to save me from having to do this when I’m fifty, unless I’m too tired, in which case I fall asleep on the sofa, or a chair on the mezzanine, or a stack of sofa pillows in the back office. I’ve trained myself to wake spontaneously at the ring of the front doorbell or the ding of the elevator.

At seven, I go home and strip down to my underwear. I drink low-grade chardonnay and vaporize weed until I pass out. Even though I am perpetually exhausted, I still find it hard to sleep. Often I am unable to doze off until well past noon. Then I get in a few fitful hours and wake up with a hangover. I take a handful of aspirin and drink energy drinks until my heart feels like it’s going to detonate.

Five Hour Energy tastes like Jolly Ranchers and paint thinner, but it delivers the same running-on-empty, twitchy, just-want-to-lie-down-on-the-cool-tiles-and-die buzz you get from truck-stop speed. If you’re going to do the dishes, or brush the cat, or tear little shreds of paper into smaller shreds of paper, it’s the only choice. The extra-strength version makes you cry a little choking it down, and the tears remind you of your absent father, or any one of a litany of ruined relationships. A bloom forms inside your mind. You feel lighter than air, scintilla of ash wafting over a campfire. You can fly.

On Wednesday, I usually try to stay awake all day and not drink anything so I can get a normal night’s sleep, so I can get up at a reasonable time on Thursday, hopefully clear-headed enough to write for two to four hours. I often miscalculate and fall asleep in the afternoon, or I end up drinking, pass out, and wake up horribly hung-over in the late evening. I just wake up and keep drinking in these instances. On Saturdays, I try to live a normal life. On Sundays, the whole process begins again.

I have wandered this strange limbo for ten years now, and I have finally decided it’s time for a change. I’m going to cure myself. I’m going to stop drinking energy drinks to wind myself up and NyQuil to wind myself down. I have allowed the stocks of wine to deplete.

LA VITA NUOVA

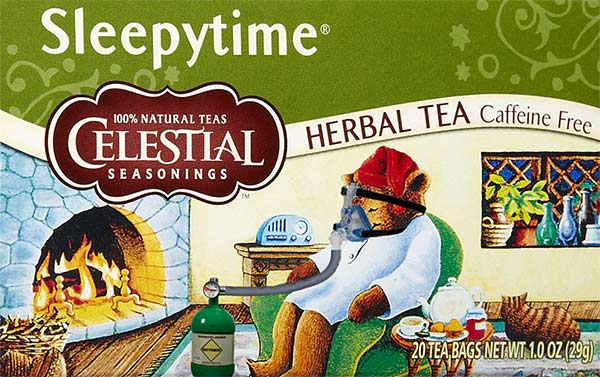

On Monday morning, I get off work, go home, and vaporize a gram of weed. I take two gel caps of the valerian that Jen bought at a health food store sometime last century. Valerian is the plant from which they derive the drug Valium, but—unaltered—its soporific effects are debatable. But I’m not taking any chances. I pair the valerian with a cup of Celestial Seasonings SleepytimeTM tea, a soothing blend of chamomile, spearmint, and lemongrass.

Waiting for the water to boil, I examine the illustration on the tea box.

The Sleepytime Bear sits by a crackling blaze in a green overstuffed chair, dozing in his white nightshirt and jaunty red nightcap, a tiger-striped tabby lounging on the carpet nearby, the blue light of evening filtering through the rustic wooden mullions of a picture window. A side table is laden with a tea tray—a round-bellied teapot, some muffins and jam. The bear has an old-fashioned Art Deco radio. He’s probably listening to Garrison Keillor on NPR. One imagines that this might be his reward for a long day of gutting salmon on the banks of the Copper River, or overturning trashcans in trailer parks. Also, he has been fitted with a CPAP face-mask in an effort to combat the debilitating effects of sleep apnea.

I take my steaming cup of SleepytimeTM into the living room.

I decide to watch videos of narcoleptic horses until I fall asleep.

NARCOLEPTIC HORSES

Although far from common, a significant number of horses suffer from equine narcolepsy. There are dozens of YouTube videos of horses shuffling, leaning, nodding out, and collapsing into heaps in paddocks—enough to fill many a sleepless night.

While narcolepsy in humans is characterized by spontaneous catalepsy and REM sleep triggered by extreme emotions—crying, laughing, surprise—narcoleptic horses simply fall asleep, occasionally injuring themselves when they fall, but usually collapsing harmlessly into the hay or onto piles of blankets.

There is something calming about watching the narcoleptic horses nod and slowly collapse, like buildings, like empires. Horse’s unseeing eyes lolling skyward, reflecting trees, fences, clouds, galaxies.

I find it difficult to sleep without alcohol, but the SleepytimeTM, the valerian, and the weed eventually do the trick. I fall asleep on the sofa around noon.

. . . the pony I’m riding is falling asleep. She is one of the My Little Pony ponies. Her name is Rainbow Dash, and, although she is the best flier in all of Equestria, she stumbles over tree roots in the path. Trotting across a meadow, she collapses. I lose consciousness too, and we careen into a soft blue bed of poppies, plunging headlong into their cloying fragrance . . .

I wake up on the sofa. It’s dark outside. Although I am not hung-over, I am impossibly groggy. Jen is working nearby, editing real estate photos and watching YouTube videos about fat people trying to lose weight, a new obsession. I skip the energy drinks; I have a cup of black coffee instead. We go jogging. On the Biltmore bridge the Japanese lanterns cast their faint glow on glittering sidewalks. Cars swish past. Horns honk. There is a dead muskrat on the roadside, toothy grin and eye socket.

I stamp my time-card at eleven. I run reports, I check credit card tallies, I correct errors. I print registration cards for the next day’s guests. I program key-cards. I prepare breakfast cards and comment cards. I count the cash drawer. I settle the books.

Around three a.m. I hit the wall.

I’m so groggy I can’t keep my eyes open. My arms and legs feel slack and heavy. It is as if there’s a weight on the back of my neck, pushing my head down towards the desk. If I had a pillow I’d just lie down and sleep. I yawn, spasmodic yawns that split my head down the middle, yawns that make me even more tired, that do nothing to alleviate the overwhelming need I feel to stop, drop the keyboard, and slide down onto the floor behind the desk, curl up and sleep . . .

I’m so groggy I can’t keep my eyes open. My arms and legs feel slack and heavy. It is as if there’s a weight on the back of my neck, pushing my head down towards the desk. If I had a pillow I’d just lie down and sleep. I yawn, spasmodic yawns that split my head down the middle, yawns that make me even more tired, that do nothing to alleviate the overwhelming need I feel to stop, drop the keyboard, and slide down onto the floor behind the desk, curl up and sleep . . .

. . . I am standing on the shore at night as a salt breeze blows across the water. The moon is low and bright, its reflection like quicksilver on the undulating wave tips. Lanterns glimmer off in the darkness; a junk on the Gulf of Siam . . .

Ding!

I wake up on the hotel lobby sofa. It is 4 a.m. The elevator bell has sounded, and there is a soft hum of machinery as the car ascends—ding—to the second floor—ding—third floor—ding—fourth floor. I get up, smooth my hair—ding—the elevator is on its way back down—ding—I cross the lobby to the desk—ding—I straighten my tie—ding—the elevator doors open. A sleepy woman with tousled white hair and wearing sweatpants dragged across the busy rust and ocher carpeting by two panting squirming corgis.

“Good Morning!”

“Good Morning!”

I open the street doors and let them out. Five minutes later, they return. I lock the street doors, wait five minutes, and reclaim my sofa.

When I get off it’s the same routine as before—vaporize weed, drink SleepytimeTM, pop valerian caps, watch videos of narcoleptic horses.

I really want a glass of wine.

The SleepytimeTM Bear has begun to irk me, his smug sleepy grin, his humble lodgings. Is he really dozing, or is he concentrating? Possibly gone off into the astral plane. Maybe The SleepytimeTM Bear is actually some sort of REM sleep vampire who feeds on the delta brainwaves of insomniacs, keeping them asleep long enough to feed, while their life force slowly ebbs away. On the astral plane, he flies out in darkness on great bat-like wings, scouring the countryside, the valleys and thoroughfares of the night echoing with his bloodthirsty cries.

I eventually fall asleep on the sofa.

. . . I am standing on a window ledge on the fourteenth floor of an apartment building, holding hands with Art Linkletter’s daughter, Diane.

“The clouds look remarkably firm,” Diane says.

“They certainly do,” I reply.

It’s getting crowded up there. Also lined up along the ledge are Jim Morrison and several ruined Wall Street brokers from the crash of ’29. One by one, they step out onto the passing clouds—My Little Pony clouds, pink ones, blue ones—and plummet straight through. Nobody seems especially concerned by this . . .

When I wake up I feel strange, insubstantial. Jen is home. I drink a cup of black coffee. We go jogging. During the jog, I feel groggy, my legs heavy. I want to succumb to the inertia, to collapse onto the sidewalk and sleep, and wake up nibbled by raccoons in the dark—they’ve mistaken me for carrion. That would suit me. Or to wake up on a rubbish barge in a harbor somewhere, also nibbled by raccoons. Everywhere scavenging raccoons. I realize that I’m laughing as I jog. Jen gives me a strange look. Tears are streaming down my face.

Ego-surfing a few years back I discovered Larry Benner, the Versatile Artist Supreme. Most of the other Larry Benners out there are insurance salesmen, real estate agents—stubby middle-managers with waxy foreheads and closets full of plaid jackets. But Larry Benner, the Versatile Artist Supreme was a jack-of-all-trades showman in the first half of the twentieth century. He played the musical saw and performed ventriloquist acts, he did sleight-of-hand, Punch-and-Judy shows, and, sadly, blackface. He traveled the world, performing, “with the greatest success throughout the United States, Canada, Hawaiian Islands, Philippine Islands, China, Japan, Malaya, Sumatra, and Java.” He also hosted a flea circus, and, at the end of the twenties, he choreographed the burlesque review Larry Benner’s Fantasies of 1929, also known as Larry Benner’s Midnight Follies.

On the way to work we stop at Harris Teeter and I go into microsleep at the self-check. Possibly triggered by All I Have To Do Is Dream by the Everly Brothers playing on the PA. I wander the aisles in search of something, macaroni and cheese, or eggs. At the self-check I’m scanning items. The bar-code reader makes a ding every time I pass an item over the scanner. I peer inside, into the gleaming silver guts of the thing, and there I am, staring back. Ding—a bottle of low-grade chardonnay for Jen—ding—Annie’s white cheddar macaroni—ding—a nine pack of toilet paper, double rolls, on sale, can’t pass it up—ding—I have the feeling of fluttering bird, fluttering bird at the window, fluttering bird in the darkest corridors of my mind—

I stamp my time-card at eleven. I run reports, I check credit card tallies, I correct errors. I can’t concentrate. The usual boost I get from the Five Hour EnergyTM is gone. Coffee is insufficient. I can’t think, I drift. I find myself reading the same numbers over and over again.

. . . the sun has burned out and blind mole rats have taken over the planet. Humanity has been driven into dark burrows, forced to harvest grubs and black beetles for mole rat overlords. It is impossible to tell day from night, and slowly, over the eons, our eyelids seal shut over vestigial eyes. Sunrises and sunsets are the stuff of bedtime stories . . .

I get off at seven. I have the next four days off. I decide to stay up all day so that I can sleep soundly at night, wake up refreshed on Thursday, and get in a day of writing, possibly at the library, where the internet connection is shitty, hence less distractions.

When I get home, I watch TV with the headphones on until Jen gets up so I won’t disturb her. I watch a show about women who poison residents of a flophouse so they can collect on their life insurance policies.

Jen gets up around eight-thirty. I make her an egg on toast. I cook it too long. The yolk is rubbery, but she eats it without complaint. She takes a bath and leaves for work.

I vaporize a bowl of weed. I clean the kitchen—washing the dishes, scrubbing the counters. I make two large pots of fruit tea, which I later bottle and refrigerate. I do several loads of laundry. I clean the bathroom and take out the trash. I am sleepy, but as long as I don’t drink any low-grade chardonnay with arsenic in it (I have recently read an online article about the trace amounts of arsenic in low-grade chardonnay) I will be fine. If I succumb to the desire to drink, I will pass out by five p.m. and sleep until midnight, and the whole plan will be ruined. I brew some coffee. I sweep the floors. I watch another show about people murdering people.

I drink some wine. I pass out on the sofa. The whole plan is ruined.

. . . the stock market crash has forced the closure of Larry Benner’s Fantasies of 1929. Suddenly no one has the money to waste on burlesque reviews anymore. The girls are all on their way back to Iowa farms and disappointed parents. The buses leave the terminal every few minutes, kicking up dust and venting blue exhaust. I have decided to wait with the girls until the last of them leaves.

The lead girl, Mary, starts humming Let’s Do It, Let’s Fall in Love, from Wake Up And Dream! by Cole Porter, and several of the other girls sing along from the wooden benches in listless, hushed voices.

I am transported back in time, to opening night under the hot lights . . .

I wake up late in the evening. On the way home from jogging we stop at Harris Teeter and buy three bottles of low-grade chardonnay. As soon as we get back, I fill a tumbler two-thirds full and top it off with some of the fruit tea I made earlier (cuts down the acidity and thins the arsenic.)

By ten o’clock I am drunk, laughing at nonsense, and by midnight I am unconscious.

I wake in the middle of the night, suddenly sober. I can’t sleep. I drink myself back to unconsciousness. I sleep for fourteen hours straight, making up for the sleep incurred trying to stay up all day Wednesday.

I spend Thursday in bed. I miss the library. Jen returns home. We decide not to go jogging. By Friday I am back on the daytime schedule. I try to write, but I can’t think straight. I drink half a bottle of Five Hour EnergyTM, and half-ass a couple hours of work. For the next three days I try to maintain consciousness, but find it impossible to think.

On Sunday, it starts all over again.

OH SOOTHEST SLEEP!

You never realize how wonderful it is until it’s gone.

I had a stuffed lion once. It was a Chinese-manufactured plush toy filled with highly-flammable poly fiberfill, maned in acrylic faux fur, plastic eyes gleaming in the dark, fixed patch of a grin ironed onto its face. He and I would watch as the glow-in-the-dark sticker from the Raisin Bran box stuck to the headboard of my bed—the smiling sun appearing over the edge of the world, bringing two scoops of raisins to the children of earth—slowly faded, its excited molecules growing jaded in the darkness, and we would watch the passing car lights as they swished window shapes across the walls and ceiling, and I would rub my eyes until the flashes came, the fireworks, the death throes of rods and cones, in the reckless way that children, amateurs in skin, experiment with their bodies in dangerous, sometimes irreversible ways.

And the evening blue faded to black, and the swish of cars and the muted sounds of evening lulled me into deep, restful, oblivion.

Glorious sleep!

. . . Sally and I walk along the beach as gulls wheel over the foaming surf. He is wearing his CPAP face-mask, dragging the oxygen tank through the sand. It carves a long curving groove behind us. Sally is smiling and happy.

“Today is my birthday,” he says, in his odd, high-pitched Southern lady voice. “I’m going to try to make it without the mask.”

I’m tense, worried that he might quit breathing and collapse onto the shingle like a narcoleptic horse. But he waves away my apprehensions.

“This is what I want, Larry. This is what I’ve always wanted. This is my Fantasy of 1929.”

I understand. We all have our revues to stage, our dances to choreograph.

He stops walking and turns towards the crashing surf. He tugs the elasticated straps over his head, pulling the CPAP face-mask off, letting it fall to the sand. He takes one long inhalation. He exhales. He inhales again. He turns towards me and smiles.

“I’m cured, Larry. You see? I don’t have the sleep apnea anymore.”